Vancouver’s former Olympic Village: Community Planning of Southeast False Creek as a Sustainable Legacy

Case Study prepared by Hannah Nykilchyk, Carleton University

Keywords: green communities, urban revitalization, sustainable cities, Olympic Village, legacy

- Lessons Learned

- Description

- Timeline

- Rightsholders and Stakeholders

- Heritage

- Sustainability

- Assessment and Measurement

- Works Cited

LESSONS LEARNED

The site of the Vancouver Olympic Village started as a pilot project to model a sustainable city and proved to be very successful. The City of Vancouver’s vision for the redevelopment of Southeast False Creek was to be seen as a community while serving as a learning opportunity for the application of sustainability principles (City of Vancouver, 2007). Prior to the Olympic Games, The City of Vancouver created the Greenest City Action Plan (GCAP) which featured eleven goals to achieve by 2020. The city was able to make substantial progress in each area of the targets. The mixed-use development project of the Olympic Village was the start of the progression towards these goals. In order to continue to grow towards becoming the ‘greenest city’, they must continue to have an impact, lead globally, hold accountability while remaining transparent and ensure actions are meaningful within local communities (City of Vancouver, 2021). The Vancouver Olympic Village is a successful leader in the future of green neighbourhoods. It proves that the concept of a green city is possible and can be executed by future city redevelopments. The project includes symbolic ties to the site’s historic industrial past through naming of three ‘Workyard, Shipyard and Railyard’ shoreline categories, which are reflected in the overall design and hierarchy of the flow and circulation throughout the Village.

The 2010 Vancouver Winter Olympics also initiated a cultural relationship with the local Indigenous communities. The City of Vancouver was the first Olympic games to ever include First Nations in an opening ceremony. By doing this, a partnership between VANOC, the province of British Columbia and the First Nations was started, as a foundation for the engagement of Indigenous communities in future events. In 2013, the powerful Indigenous alliance created an economic development corporation, which uses its resources to purchase within its traditional territories (ITBC, 2020).

PRESENTATION (Vancouver Olympic Village, Hannah Nykilchyk)

This slideshow was presented in class on November 24, 2022. It is a presentation of the case study about a sustainable city after the Olympic Games, that focused on how the Vancouver Olympics fostered environmental sustainability while also having several economic benefits.

DESCRIPTION

The Vancouver Olympic Village is located in Southeast False Creek (SEFC). The site consists of over twenty buildings with about 1.2 million square feet of multi-unit residential space and mixed-use development (Recollective, 2021). Prior to the 2010 Winter Olympic Games, SEFC was known as an industrial site used for harvesting forests and fishing, which later developed into an important industrial hub for manufacturing and processing (Bayley, 2009). The Vancouver Olympic Village planning committee created a design to act as a model for sustainable development based on sustainable, economic and environmental principles. Throughout the games, the Olympic Village housed 2,800 athletes (KD Engineering, 2018).

The Olympic Village has since been converted into permanent housing and the mixed-use neighbourhood has 1,100 units with approximately 250 affordable housing units and 100 modest housing units (KD Engineering, 2018). A main goal while creating this community was to ensure walkability, with housing linked to public transit and proximity to local jobs. Today, the district has achieved its goals. The Village includes 5,000 residential units, a mid-sized grocery store, retail spaces, a community centre, a non-motorized boating facility, several childcare facilities, an elementary school, five restored heritage buildings and ten hectares of public parks including playgrounds and agricultural spaces (KD Engineering, 2018). All buildings residing in the Southeast False Creek zoning have achieved LEED NC Gold certification, while the Community Centre and the net-zero energy project both achieved Platinum certification (Recollective, 2021). Southeast False Creek is a model for the green city that also considers the site’s industrial heritage, and conserves water, reduces energy and waste while being designed around people instead of cars.

TIMELINE

| DATE | EVENT |

| November 2002 | City of Vancouver Signs Multi-Party Agreement for the 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Games |

| June 2003 | Vancouver wins bid to host the 2010 Winter Olympics |

| July 2005 | City Council enacts Official Development Plan for Southeast False Creek Bylaw focusing on sustainability principles |

| January 2006 | Amendment to the Official Development Plan which reduced the requirement for affordable housing by 20% |

| April 2006 | Millennium Properties Ltd. is selected as the developer of the Olympic Village by City Council |

| December 2006 | City Council approves Neighbourhood Energy Utility operation and ownership by the City of Vancouver |

| September 2008 | Fortress advises no further funding to be advanced for the project and the City of Vancouver steps in to ensure project remains on tight deadline |

| November 2009 | Olympic Village commences phased handover to VANOC in preparation for the 2010 Winter Olympic and Paralympic Games South East False Creek community received Leed Platinum Designation |

| April 2010 | VANOC returns the Olympic Village back to the City of Vancouver at the conclusion of the Olympic games |

| February 2011 | Relaunch and rebranding of the Village of False Creek by Rennie Marketing Systems |

| December 2011 | First commercial spaces open (TD Bank, Terra Breads, Legacy Liquor Store and Village Cleaners) |

| March – August 2012 | Several more commercial spaces open (Subway, Urban Fare, London Drugs and Tap and Barrel) and the Creekside Community Centre opens |

| 2013 | Receives the Urban Land Institute award for urban open spaces |

| April 2014 | City retires debt |

| Ongoing | Homes within the village continue to be rented, purchased and managed |

RIGHTSHOLDERS & STAKEHOLDERS

Southeast False Creek is situated on the unceded territory of the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh Nations and is used by the following groups:

- The Vancouver Olympic Village is owned by the City of Vancouver in partnership with the Millennium Development Corporation

- The province of British Columbia

- Athletes during the 2010 Winter Olympics and Paralympic Games

- After 2010, open to the public, a mixed-use community with retail workers, residents and visitors

The jurisdiction of this project applies at the municipal level and the developmental decisions of this project were made by the City of Vancouver in collaboration with the Province of British Columbia.

Organizations: These organizations participated in the organization and engagement of the community in preparation for the redevelopment of the Winter Olympics Village:

- Olympic Legacy Reserve Fund (OSS) – Developed by the 2010 Winter Games committee to facilitate, support and implement Social Sustainability Initiatives in the impacted inner-city communities

- Vancouver Organizing Committee (VANOC) – non-profit organization responsible for planning, organizing, financing and staging the 2010 Winter Olympic Games

Consultants: Several different consultants were engaged on this large, time-sensitive project:

- Acton Ostry Architects – rehabilitation of The Salt Building

- Recollective Consulting – sustainability measures, LEED Certification, Net Zero Modelling, and Funding Research

- PWL Partnership – assisted the City of Vancouver with the Official Community Plan and Public Realm Design Guidelines

- KPMG LLP – performed comments of the status of the development of Southeast False Creek and associated financial expenses

Several architects and engineers were responsible for the design and construction process of the Winter Olympic Village, the main ones include:

- Architects:

- Merrick Architecture

- Robert Ciccozzi Architects

- Heatherbrae Architects – responsible for the Four Host First Nations Pavillion

- Fast + Epp – created the pre-fabricated elements of the Four Host First Nations Pavillion

- Engineers:

- KD Engineering

- Morrison Hershfield Group Inc.

- Cobalt Engineering

- Stantec

HERITAGE

The approach to heritage discussed in this case study is at the scale of the larger site and with reference to creating a legacy of future heritage.

Natural heritage: Prior to becoming the site for the 2010 Winter Olympic Games, SEFC was an industrial hub rich in history. False Creek was populated by several First Nations including the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh peoples (Bayley, 2009). The area was named after a European sea captain when they were travelling down the river in 1859 and came to a dead end (City of Vancouver, 2014). Beginning in the late 1800s, SEFC became occupied by shipbuilders, sawmills, foundries, metal works, a salt refinery and a public works yard (Bayley, 2009). During this industrial boom, the southern part of False Creek became the first housing development to appear along the shoreline.

The shoreline plays an important role in the natural heritage of this site. The original shoreline ran along First Avenue, making the current development non-existent. Over the years, the material was taken from several sources including a railway cut and ash from an incinerator to make filling in the shoreline possible (Bayley, 2009). The sustainable development project wanted to include symbolic ties to the site’s historic industrial past. This was done by creating three distinct categories along its shores: Workyard, Shipyard and Railyard (Bayley, 2009). These distinct categories were also applied throughout the design process of the Official Development Plan and reflect the overall design and hierarchy of the flow and circulation throughout the Village.

Cultural heritage: Vancouver is a city rich in cultural heritage and diversity. An important element of the Village was to connect symbolic elements to the historical past of the district. The redevelopment of SEFC accelerated the rehabilitation of several historic buildings within the area. The Salt Building is an iconic landmark located on First Avenue and Manitoba street, the former shoreline of False Creek (Recollective, 2021). The building underwent a series of seismic upgrades and rehabilitation to prepare to be a central gathering space for athletes of the Olympic Games. The rehabilitation included restoration of the exterior while aligning the building with the new street level (Recollective, 2021). While several character-defining elements, including the old windows and doors, were preserved, signage was re-created from archival photos (Acton Ostry Architects, n.d). Today, the Salt Building remains one of the few heritage buildings to achieve LEED Core and Shell Gold certification (Recollective, 2021). Without the redevelopment of this area for the Winter Olympics, it is likely the Salt Building would have continued to deteriorate. Today, the building is a focal point of the neighbourhood where residents walk to grab a coffee, share a meal or taste a variety of craft beers. A more detailed case study of the Salt Building is found elsewhere on this website.

Southeast False Creek is situated on the unceded territory of the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh Nations. During the Vancouver Olympic Games, a temporary structure named the Four Host First Nations Pavillion, showcase dCanada’s aboriginal heritage and cultural heritage (Heatherbrae, n.d). The building was designed to be easily movable and each part was pre-fabricated with the longhouse portion being repurposed as a permanent legacy after the games (Fast + Epp, n.d). It now serves as an education centre for the Musqueam FIrst Nations. Located on their lands, Metro Vancouver’s first inhabitants can showcase their art, stories and sacred culture and language (Fast + Epp, n.d).

SUSTAINABILITY

The main goal of the redevelopment plan was to demonstrate a comprehensive approach to sustainability that expands throughout the region. In order to create a sustainable neighbourhood, the following urban design principles were integrated: stewardship of ecosystem health, economic viability, priorities of performance targets, cultural vitality, liveability, housing diversity and equity, education, participation, accountability, adaptability, integration, the spirit of place and a complete community (City of Vancouver, 2007).

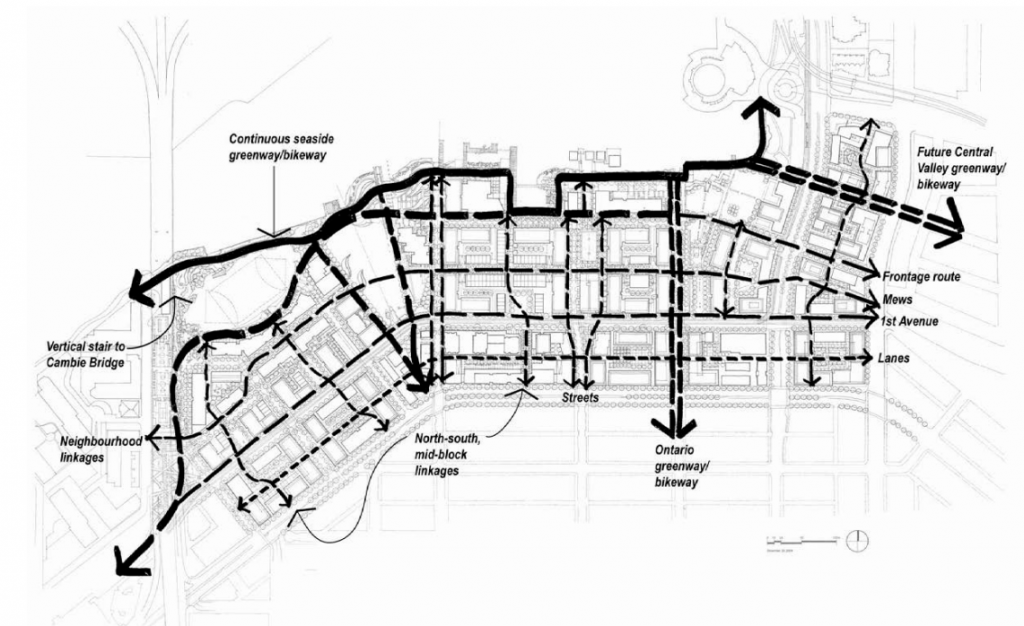

Environmental Sustainability: The main design principles integrated to enhance the environmental sustainability features include: energy-efficient buildings, stormwater management, solid waste and recycling programs, landscaping, urban agriculture, habitat and eco-systems and green buildings. The village design has a major focus on the building envelope, green roofs and building orientation (City of Vancouver, 2007). This allows natural light and ventilation to be maximized in each space, minimizing the use of HVAC systems and artificial lighting. SEFC is equipped with a natural stormwater management system that includes bioswales and natural wetlands (Recollective, 2021). The landscaping within the village was carefully chosen to feature drought-tolerant landscapes that minimize irrigation while providing edible landscaping and community gardens to be shared by the residents (City of Vancouver, 2007). The main goal of the SEFC neighbourhood was walkability. The neighbourhood layout prioritizes pedestrians as the most important, followed by bicycles, transit and vehicles (City of Vancouver, 2007). Lastly, all buildings within the community must achieve a green building status. The neighbourhood surpassed this goal by achieving a net-zero building while also receiving LEED Platinum designation for the neighbourhood as a whole.

SEFC also created a natural ecological habitat known as Habitat Island. The man-made island was created as a sanctuary for wildlife and plants. Deep layers of soil have been added to aid with nourishment while providing a home for several insects, small animals, crabs, starfish and several other small creatures (City of Vancouver, n.d). The island prohibits cyclists and dogs in order to preserve its natural elements.

Social Sustainability: To achieve social sustainability, SEFC considered equity, social inclusion and adaptability. The goal of the development was to meet basic needs by providing adequate, affordable housing. This was achieved by dedicating 20% of the combined sections of 1A, 2A and 3A to affordable housing (City of Vancouver, 2007). The mixed-use development has been dispersed throughout all areas in order to create opportunities for healthcare offices, clinics and family practice networks. The local community centre is also designed to house affordable child care (City of Vancouver, 2007). The local businesses not only provide jobs but promote locally sourced and purchased goods. The 2010 Winter Games promoted local employment with initiatives, one being “Sew a Legacy”. The program provided employment to several women while offering skills training in sewing (City of Vancouver, 2010). The sewers created bags from recycled road signs and distributed them to children within schools (City of Vancouver, 2010).

Cultural Sustainability: The Olympic Games inspired initiatives that promote the culture of Vancouver. The Official Development Plan acknowledges the unique characteristics of the area and a total of five heritage buildings were able to be preserved throughout the redevelopment process (City of Vancouver, 2007). The Games also helped enable the inclusion of Indigenous communities. The Olympic Committee created an Aboriginal Youth Sport Legacy Fund which enabled Indigenous youth to participate in snowboarding while improving their quality of life and encouraging empowerment (International Olympic Committee, 2020).

Sawtooth cut of the former industrial shoreline preserved with former footprints of heritage buildings. Source: Official Development Plan By-laws: Southeast False Creek (vancouver.ca)

Economic Sustainability: In order to achieve economic sustainability, SEFC set goals to provide economic security, local self-reliance and an ecological economy with an economic advantage. After the 2008 recession, their main goal was to create security for the locals which was achieved by employing residents throughout construction with equitable hiring practices (City of Vancouver, 2007). The idea of self-reliance is that members of the community are fully capable to complete daily activities without needing to rely on transportation with local products being affordable to low-income households (City of Vancouver, 2007). The goal of the community is to develop an environment where businesses have implemented recycling programs and the community receives economic gains by conserving energy, reducing waste and being cautious of their carbon footprint (City of Vancouver, 2007). Overall, the goals of sustainable economic development connect with the idea of pride and identity within a greater community.

Map of pedestrian routes. Source: Official Development Plan By-laws: Southeast False Creek (vancouver.ca)

These sustainable practices all rely on the support and participation of the community. The main goal is to offer equitable opportunities to low-income and modest households while contributing to a greener future. By assessing the sustainable development goals as well as comparing Southeast False Creek to the Greenest City Action Plan, it proves to be a step in the right direction towards a greener world.

ASSESSMENT AND MEASUREMENT

The 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were adopted in 2015 by the United Nations. The Vancouver Olympic Village works towards achieving these goals specifically the following four:

SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy

Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all

| Target Goal | Case Study- evaluation by author |

| Target 7.1: By 2030, ensure universal access to affordable, reliable and modern energy services | Throughout the village, residents can find electric vehicle charge stations and solar panels on the majority of the roofs. |

| Target 7.2: By 2030, increase substantially the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix | Net-zero energy buildings were achieved with the senior residence being a pilot project of a fully functional net-zero energy building. |

SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth

Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all

| Target Goal | Case Study- evaluation by author |

| Target 8.3: Promote development-oriented policies that support productive activities, decent job creation, entrepreneurship, creativity and innovation | 2500 full-time jobs were created leading up to and during the Winter Games as well as throughout the construction of the village. |

| Target 8.8: Protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers | Vancouver 2010 fabrication shop was created as a learning opportunity for low-income members to receive training and employment. |

SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable

| Target Goal | Case Study- evaluation by author |

| Target 11.1: By 2030, ensure access for all to safe and affordable housing | Affordable housing was designed within the village with dedicated buildings to lower income households |

| Target 11.2: By 2030, provide access to safe, affordable, accessible and sustainable transport systems for all, improving road safety, notably by expanding public transport | Cars are not a priority in the village and the diagrams show how the community was designed around trains, bike paths and walkability as a whole. |

| Target 11.4: Strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage | The Salt building was able to be restored with the city divided into 3 sections to keep historical ties to the past. |

SDG 14: Life Below Water

Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development

| Target Goal | Case Study- evaluation by author |

| Target 14.1: By 2025, prevent and significantly reduce marine pollution of all kinds | Parks along coastlines and Habitat island conserved to promote marine life. No dogs or bikes are allowed on the island to help preserve it. |

Table 1: An assessment of the Sustainable Development Goals applied in the Southeast False Creek neighbourhood

The Greenest City Action Plan (GCAP) features ten sections of goals and SEFC hits each one:

| Goal | Targets | Case Study- evaluation by author |

| Climate and Renewables | Reduce community-based greenhouse gas emissions by 33% from 2007 levels by 2020. | All apartments have low-flow water systems as well as rooftop solar panels. The village also encourages walking and cycling. |

| Green Buildings | Require all buildings constructed from 2020 onward to be carbon neutral in operations. | All buildings in the Olympic Village have achieved LEED Gold certification and the neighbourhood has achieved LEED Platinum. |

| Green Transportation | Make 50% or more of trips by foot, bicycle and public transit. | The neighbourhood is very walkable and is easily accessible by both bus and train. The Village is designed with the pedestrian as the priority. |

| Zero Waste | Reduce total solid waste going to the landfill or incinerators by 50% from 2008 levels. | Each zone includes adequate waste management systems to ensure a minimum of 50% landfill diversion (City of Vancouver, 2007). |

| Access to Nature | Ensure that every person lives within a five-minute walk of a park, greenway or green space. | Parks and open public space were the centerpoint of the design layout and connect adjacently to bike paths and walking trails (City of Vancouver, 2007). |

| Clean Water | Meet or beat the most stringent drinking water quality standards and guidelines. | The water systems within the village are designed around the GCAP Framework and avoid the use of potable water from the municipal system wherever possible (City of Vancouver, 2007). |

| Local Food | Increase city-wide and neighbourhood food assets by a minimum of 50%. | There are several locally run retail spaces within SEFC and several local shops like the Salt Building which houses a restaurant, bakery and brewery. |

| Clean Air | Meet or beat the most stringent air quality guidelines. | Several trees, green areas and gardens to help with air filtration and also providing electric charging stations for vehicles to minimize pollution. |

| Green Economy | Double the number of companies engaged in greening their operations over 2011 levels. | Strategies have been implemented that provide local businesses with technologies to build on recycling practices (City of Vancouver, 2007). |

| Lighter Footprint | Reduce Vancouver’s ecological footprint by 33%. | Electric charging stations and the village built at the pedestrian scale not encouraging the use of cars |

Table 2: An assessment of how the Vancouver Olympic Village in Southeast False Creek aligns with the Greenest City Action Plan (GCAP) developed by the City of Vancouver.

WORKS CITED

Books/Book chapters/Journal articles

- “9. Domtar Salt Building (1931) .” Heritage Vancouver, 2002, heritagevancouver.org/top10-watch-list/2002/9-domtar-salt-building/.

- Bayley, Roger. “Get the Challenge Series Booklet.” 07_Living Today + Tomorrow – The Challenge Series, 2007, www.thechallengeseries.ca/get-the-challenge-series-booklet/chapter7/.

- Bayley, Roger. “History.” History – The Challenge Series, 2007, www.thechallengeseries.ca/chapter-01/history/#:~:text=Southeast%20False%20Creek%20became%20an%20important%20industrial%20hub,on%20the%20site%20today%2C%20its%20legacy%20is%20far-reaching.

- Ioc. “Vancouver 2010: Setting the Standard for Sport, Sustainability and Social Legacy – Olympic News.” International Olympic Committee, IOC, 12 Feb. 2020, olympics.com/ioc/news/vancouver-2010-setting-the-standard-for-sport-sustainability-and-social-legacy/.

Policies and reports

- City of Vancouver. Greenest City 2020 Action Plan, vancouver.ca/files/cov/2021-greenest-city-action-plan-final-update.pdf.

- City of Vancouver. “Home | City of Vancouver.” Olympic Social Sustainability Initiative Projects, Aug. 2010, vancouver.ca/files/cov/Great-beginnings-OSSFinal_Report.pdf.

- City of Vancouver. “Official Development Plan of Southeast False Creek.” Laws, Aug. 2007, bylaws.vancouver.ca/odp/odp.htm.

Websites

- “The 17 Goals | Sustainable Development.” United Nations, United Nations, sdgs.un.org/goals.

- Acton Ostry Architects. “Salt Building Restoration 2010 Olympic Village Vancouver.” Acton Ostry Architects, 20 Jan. 2019, www.actonostry.ca/project/salt-building-vancouver/.

- City of Vancouver. “Olympic Village.” City of Vancouver, vancouver.ca/home-property-development/olympic-village.aspx#redirect.

- Consulting, Recollective. “Vancouver Olympic Village.” Recollective Consulting, 20 May 2021, recollective.ca/project/vancouver-olympic-village/.

- KD Engineering. KD Engineering, 2018, Southeast False Creek – Olympic Village, kdengineering.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/KDE_2018_GreenBuildingBrain.pdf.

- PWL Partnership. “Southeast False Creek: PWL Partnership.” Southeast False Creek | PWL Partnership, n.d., www.pwlpartnership.com/case-studies/southeast-false-creek.

- Four Host First Nations Musqueam Pavilion – Fast + Epp

- https://www.heatherbrae.com/portfolio_page/four-host-first-nations-pavilion/

- “World Class Innovation at Southeast False Creek Informs Metro Vancouver Reference Panel.” Green Infrastructure, 7 June 2009, waterbucket.ca/gi/2009/06/07/world-class-innovation-at-southeast-false-creek-informs-metro-vancouver-reference-panel/.