Transforming a Brownfield by the Don River: Toronto’s Corktown Commons Park

Case Study prepared by Marlo Fabella, Carleton University

KEYWORDS: Corktown Commons, Urban Parks, Flood Prevention, Well-Being, Social Gathering, Renewable Energy, Ecological Landscape, Cultural Landscape, Toronto, Don River

- Lessons Learned

- Description

- Timeline

- Rightsholders and Stakeholders

- Heritage

- Sustainability

- Assessment and Measurement

- Works Cited

LESSONS LEARNED

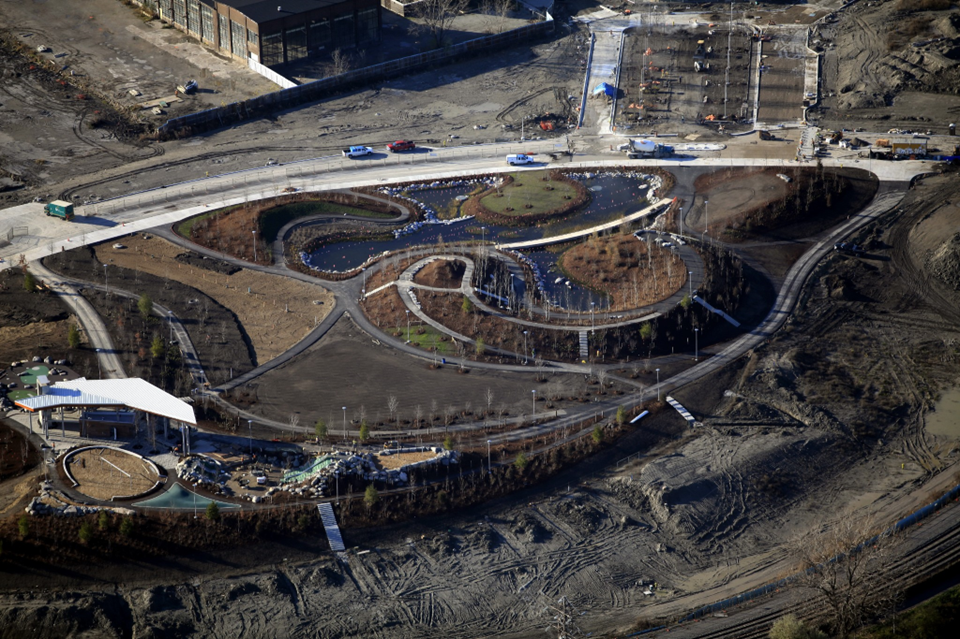

The Corktown Commons is a compelling example of the transformation of brownfield into an environmentally and socially sustainable site through the combination of public park design and green building methods. It occupies a 9.3 hectares site that has been seen as a difficult plot of land to work with for decades due to the effects of the industrialization. The history of this once ecologically rich cultural landscape highlights the notion that funded efforts alone do not guarantee a solution to the ecological restoration issues and that specialized knowledge and experience on the team is vital to a project’s success. The stakeholders and restoration team between the first attempts to restore the area and the most current team displays the improvements in expertise, with more than a third of the team is comprised of properly trained professionals in the ecological and environmental engineering field alone. In the same breath, available technology and documentation resources during the design phase play an important role in the progress of the intervention.

In the future projects like the Corktown Commons Park could be improved by amplifying the role of Indigenous communities, especially considering their involvement and presence in the cultural landscape surrounding major urban waterways, such as the Don River. Waterfront Toronto has since begun to team up with Johnston Research Inc., who emphasize Indigenous perspectives, in projects that are currently in the works. Public sculptural works are being installed by Indigenous artists, Amy Malbeuf, Jordan Bennett and IOTA Studios, on adjacent streets that pay homage to the “Don River and historical floods that affected the area in past eras”. Bennett states further that “our ability to do this as Indigenous people is found in our ancestral technologies, ability to adapt, and use of humour and play to cope” (Bredin, Waterfront Toronto, 2022).

PRESENTATION

DESCRIPTION

The union between park and sustainable design that is seen in the Toronto’s Corktown Commons Park involves the synthesis of a new system that prevents flooding into Toronto’s downtown core. Led by Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates and developed under the West Don Lands Precinct Plan, this 9.3-hectare project incorporates three major divisions of the site that align with the natural contours of the existing floodplain and that reflect the state of the natural environment. These sections include the “Wet Side”, where flood protection features are guarded by the absence of planted trees, the “Dry Side”, which promotes social gathering and personal well-being, and finally, the “Northern Entrance”, which connects the park to downtown Toronto and involves the surrounding built environment.

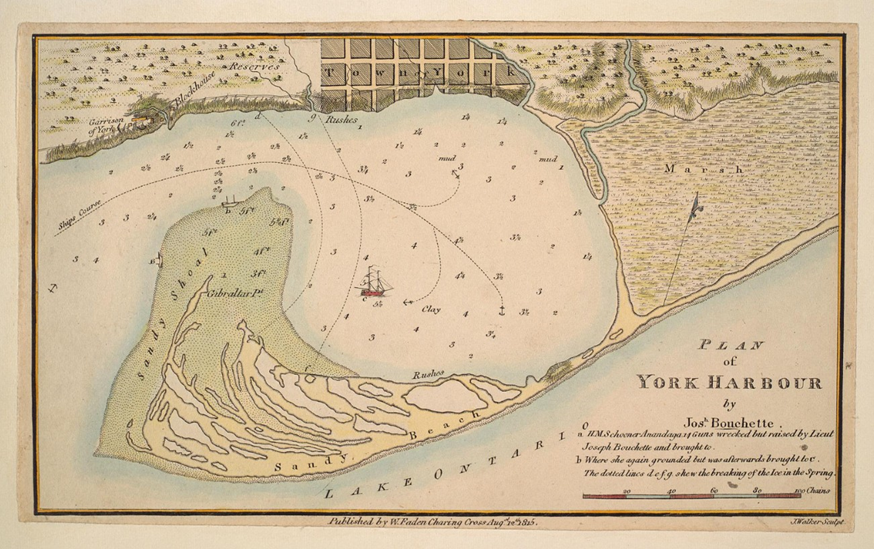

Previously used as a resource for Indigenous Peoples and the largest and most biodiverse freshwater wetlands region in North America, the Lower West Don River and Ashbridges Bay Marsh became a working landscape for Toronto during the 1850’s, being used for transportation of goods and a part of a waste disposal system. The rich ecology of the site and of the adjacent Ashbridges Bay Marsh, which is no longer present due to decades of harsh human interaction and development, is what is emphasized in the new design of Corktown Commons Park. The ecological value and heritage are restored through the park’s design and highlights the Don River’s role as a cultural landscape in Toronto. According to Parks Canada, a cultural landscape is “any geographical area that has been modified, influenced or given special cultural meaning by people”, which is relevant to the Corktown Commons Park site and its various layers of use and significance throughout history (Parks Canada, 1994).

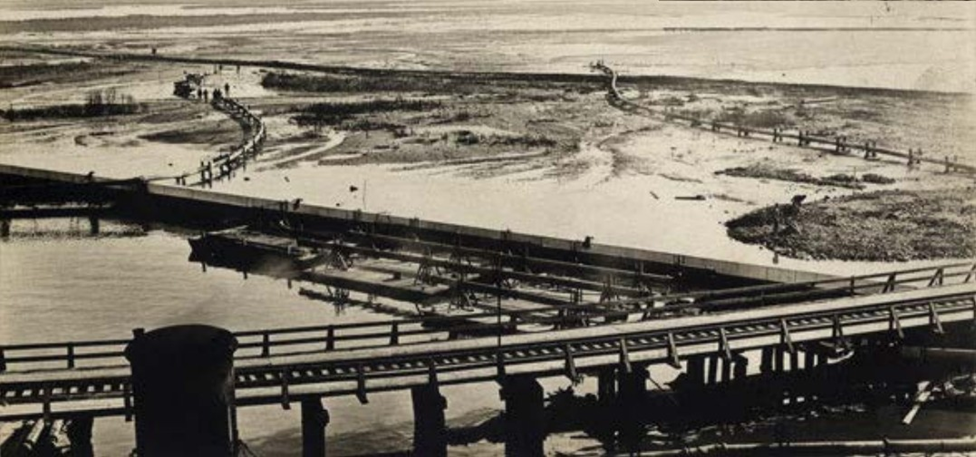

Until 2012, the soil on site was too saturated with water to be urbanized. Clay soils and fill material were then added onto the site to create a flood protection landmass. However, this form of protection failed to benefit the residents, so soil was added to provide for the local wildlife and the health of the natural environment (i.e. tree canopies, propagation of native plants on the site and pollinator forage). As heritage and archaeology Professor Denis Byrne writes, “[the Anthropocene’s] archaeological identifiers include vastly extensive layers of ‘artificial ground’ and of ‘Anthropocene rock’ consisting of concrete, bitumen, and other artificial strata” (Byrne and Ween, Bridging Cultural and Natural Heritage, 2015). The history of the ground itself is relevant to the notion of artificial ground and how not all ground that is touched by humanity is unsalvageable.

TIMELINE

- From time immemorial: Indigenous presence along the Don River, with pottery being made from clay deposits and Wendat longhouse villages. These groups include the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation, the Anishinabewaki, and the Haudenosaunee.

- 1787: Purchase of “York” (Toronto), from the Mississaugas of the New Credit to the Crown, was revisited in 1805 to clarify the terms, and was an area of dispute until 2010, when the Government of Canada paid $145M for the lands based on its historic value to the Mississaugas

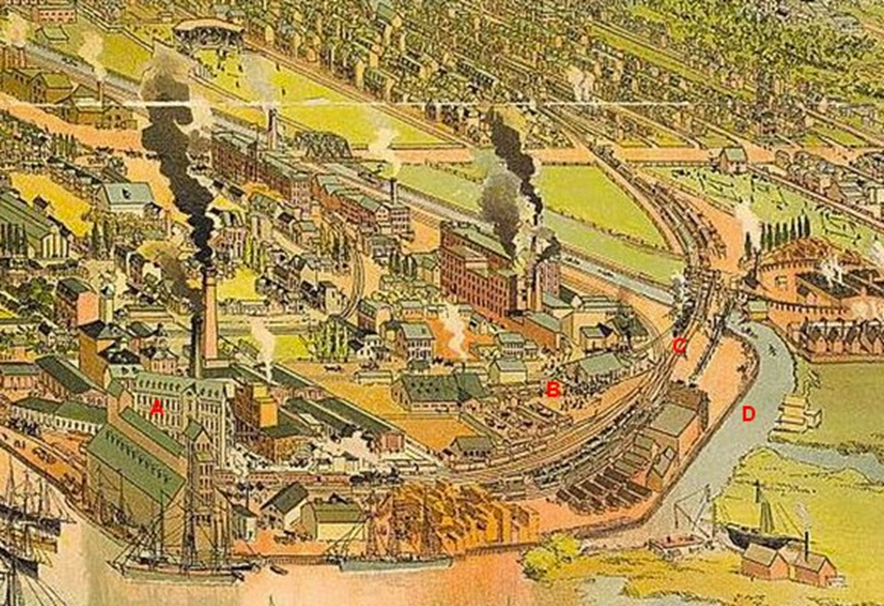

- 1879: Don River is a working landscape (Industrial Revolution) and the William Davies plant brings economic success to Toronto at the cost of the Lower Don River

- 1927: The William Davies plant is left as a brownfield when the company relocates out of downtown Toronto due to a lack of market and financial difficulties

- 1954: Hurricane Hazel highlights decaying and contaminated status of waters and soil

- 1886: Don River Improvement Project created to clean the river landscape due to sewage filling the area in 1875, which included filling, draining, channelizing, and dredging the Lower Don River. However, the project failed because ecology knowledge amongst stakeholders was not as deeply understood (engineers, contractors, health professionals, politicians)

- 1987: West Don Lands taken by Government of Ontario under Toronto mayor Art Eggleton to build a Ataratiri community, but resulted in the abandonment of the West Don Lands

- 1992: City of Toronto and Government of Ontario invests $350M to attempt cleanup, not enough because of contaminated soil

- 2001: Waterfront Toronto is created to aid in revitalizing waterfront neighbourhoods

- 2003: Planning begins under the West Don Lands Precinct Plan (Project Scope, Waterfront Toronto)

- 2005: Waterfront Toronto develops framework to guide all waterfront projects and the West Don Lands Precinct Plan is approved by Toronto City Council (Waterfront Toronto)

- 2012: Construction completed

- 2013: moved to Corktown Common from High Park as part of the West Don Lands Public Art Strategy

- 2014: Official opening of Corktown Commons

- 2016: Northern Entrance opens

RIGHTSHOLDERS AND STAKEHOLDERS

As previously mentioned, the lack of Indigenous input throughout this project is a lesson to be learned from, especially considering the historical and cultural importance of the nearby waterways that played a significant role to communities such as the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation, the Anishinabewaki, and the Haudenosaunee that once habited the land. This is especially important considering that according to the City of Toronto’s Urban Indigenous Action Plan, 85% of Indigenous peoples in Ontario live in urban areas just like Toronto (City of Toronto, 2018).

A variety of stakeholders and rightsholders were involved and consulted in the process of the Corktown Commons Park construction. This list also sheds light on the different efforts and desires from the authoritative and local community to revitalize this neighbourhood, as seen with groups such as Bring Back the Don, the groups led by the West Don Lands Precinct Plan (which oversees the greater Corktown area of about 32 hectares, and works with housing units on the site) and the municipal, provincial and federal government.

- Rightsholders and governments

- Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation

- City of Toronto, Government of Ontario, Government of Canada (Waterfront Toronto)

- Communities, associations

- Bring Back the Don

- West Don Lands Committee

- Residents of the Corktown Commons and Lower Don Lands

- Architects, designers

- Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates: Lead architecture firm

- Maryann Thompson Architects: Park pavilion design team

- ARUP: Extended design team

- Design teams associated with the West Don Lands Precinct Plan

- Urban Design Associates and DTAH: Precinct Plan and Block Plans

- The Planning Partnership, PFS Studio & Co.: Public realm and urban design teams

- Jill Anholt: Public art consultant

- ERA Architects: Heritage consultants

- Ecology and engineering

- Pine and Swallow Environmental

- Greenberg Consulting

- Great Eastern Ecology

- Creative Irrigation

- The Planning Partnership

HERITAGE

Natural Heritage: The West Don Lands with the nearby Ashbridges Bay Marsh was at one point the most biodiverse freshwater wetlands in North America, and are seen as significant because of their route from Lake Ontario through the city of Toronto. Species such as eel, bass, salmon, and more once filled the waters and supported a variety of migratory birds, wild ducks, and swamp blackbirds in the region (Stinson, The Heritage of the Port Industrial District, 1990). By the end of the nineteenth century, however, the aquatic ecosystem of the wetlands had completely decayed (Waterfront Toronto, History of the Portlands, 2019). These lands of Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation provided clay as a resource and waterways that aided in agriculture and transportation. After the purchase of York (Toronto), the Don River proved to be beneficial as a transportation route but was unfortunately used for waste disposal systems, resulting in the deterioration of its original condition. Since the river was not held to be an urban river of high importance given its smaller size in comparison to rivers in cities such as Chicago, Detroit and Pittsburgh, there was a lack of significant conservation attempts and the Don was therefore left to deteriorate during and after the Industrial Revolution. As Laura Solano writes “sacrificing the Don River was the price of progress” (Solano, Journal of Green Building, 2017).

Cultural Heritage: The Corktown Commons neighbourhood and the Don River area are rich in history; the cultural landscape of the site ties in with its toponymy. The Don River’s name comes from Lieutenant Governor Simcoe, who was reminded of the River Don in Yorkshire, England, which had a similar wide valley (Richardson, Don Valley Conservation Report, 1950). The name Corktown dates back to the early nineteenth century, when groups of Irish immigrants of Protestant and Catholic denominations from County Cork populated the neighbourhood (Lemos, Corktown History Toronto, 2022).

The exact site of the Corktown Commons Park once served as an industrial site for pork processing plants and railways. The William Davies Company was at one point the largest pork packer under the British Empire and contributed to Toronto’s nickname as “Hogtown” because of its success in the industry (Rust-D’Eye et al. Cabbagetown Remembered, 1984). In fact, one of the facilities located near the Don River became the second largest pork processing plant in North America, and in 1891, the newest plant was the first in the country to use a refrigeration unit (Cabbagetown Remembered). The company was especially successful during the First World War until the 1920’s, where the market had fallen, causing William Davies Company to merger with Gunns Limited and Harris Abattoir Co. to form Canada Packers, Canada’s largest meat processing and packing company (Cabbagetown Remembered). After relocation within the Greater Toronto Area, the company merged with Maple Leaf Mills in 1991 to form Maple Leaf Foods. Today, the company’s first pork processing facility still stands on Front Street, but the plant that once occupied the land near the West Don River was demolished to make room for the Ataratiri Project during the 1990’s (Toronto Pork Packing Plant, Lost Rivers).

The Ataratiri Project, which was meant to occupy the same site as the current Corktown Commons, was introduced in 1987 by Toronto mayor Art Eggleton and aimed to provide aid in the subsidized housing crisis for about 14,000 Toronto residents. The word “Ataratiri” comes from the Wyandot (Iroquoian language) word for “supported by clay”, in reference to clay soil found in the area, and is one of the main materials used in the current Corktown Commons Park to support and stabilize the landmass that aids in preventing potential flooding. However, this project failed due to a lack of interest from private investors at the time, which led to the project being cancelled soon after its introduction. Despite the failure of the redevelopment project, a plaque has been included in the Corktown Commons Park before its official opening to honour the heritage of the William Davies company and its legacy on the site and its impact on Toronto’s food industry (Randall, As I Walk Toronto, 2014).

SUSTAINABILITY

Environmental sustainability: As seen in the list of environmental engineering and ecological-related stakeholders on the project, environmental sustainability is one of the driving components of the park. With Waterfront Toronto leading the project, the group’s mission statement focuses on “embracing short, medium, and long-term goals for brownelds remediation, reduced energy consumption, constructed green buildings, improved air and water quality, and expanded public transit,” and is in fact certified as a Gold-rated project under LEED’s Neighbourhood Development category (Waterfront Toronto). All rainfall on site is managed and retained for reuse within the park facilities and the marsh areas in the park aim to conserve the wildlife and ecological well-being of the site and water bodies. Utility sources are all found within the pavilion, and the use of passive systems in the site are revealed with the use of solar panels on the south side of the pavilion to address onsite power needs. The park’s division of “wet” and “dry” sides helps in reducing the Heat Island Effect with an efficient use of trees throughout the space, and the amount of green space contributes to the cooling of the area, especially in the summer months. Light pollution at night is also reduced because of the open space, which allows light to reach more areas without an increased amount of power being used.

Social sustainability: The Corktown Commons Park serves as a neighbourhood amenity, promoting social gathering for people of all ages and walks of life. In addition, the use of wide paths promotes walkability and biking on the site, which is complimented by the proximity to the city’s reliable transit system which connects the park to the downtown core and other amenities. As mentioned, public art installations are in the works and involve Indigenous creatives, which promotes the amplification of their narratives in relation to the site and its history.

Economic sustainability: As a neighbourhood amenity, the park makes the neighbourhood more attractive for renters and homeowners, especially younger families, as it is well-connected to the city and provides space for outdoor activity. Seeing as it is an urban park, nearby residential developments can be found with commercial spaces on the ground level, which also helps in promoting local business and is a source of employment.

ASSESSMENT AND MEASUREMENT

In terms of the site’s sustainability, there were several systems and ratings that were used to prove its efficiency and acknowledgement of green building practices. The Lower Don River West Class Environmental Assessment was used, which serves to examine the alternative flood protection systems and repercussions to avoid flooding along the Lower Don River. In addition, a partnership with Toronto and Region Conservation was conducted with the Conservation Authority Class Environmental Assessment for Remedial Flood and Erosion Control Projects and the Canadian EA Act. Both assessments secured an environmentally friendly reputation for the site, as well as the USGBC’s LEED Rating System, which awarded the neighbourhood with a Gold Accreditation under the Neighbourhood Development category. In terms of global sustainability efforts, the United Nation’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals are relevant, with the Corktown Commons Park hitting several targets in SDG’s 3, 7, 11 and 15.

LEED Gold – Neighbourhood Development*

| LEED ND Category | LEED ND Target | Project Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Smart Location and Linkage (28 points) | Prerequisites: Smart location, Imperiled species and ecological communities, Wetland and water body conservation, Agricultural land conservation, Floodplain avoidance | ✓ |

| Brownfield remediation | ✓ | |

| Access to quality transit | ✓ | |

| Housing and jobs proximity | ✓ | |

| Bicycle facilities | ✓ | |

| Site design for habitat or wetland and water body conservation | ✓ | |

| Restoration of habitat or wetlands and water bodies | ✓ | |

| Long-term conservation management of habitat or wetlands and water bodies | ✓ | |

| Steep slope protection | ✓ | |

| Neighbourhood Pattern and Design (41 points) | Prerequisites: Walkable streets, Compact development, Connected and open community | ✓ |

| Walkable Streets | ✓ | |

| Mixed-Use Neighborhoods | ✓ | |

| Reduced Parking Footprint | ✓ | |

| Connected and Open Community | ✓ | |

| Transit Facilities | ✓ | |

| Access to Civic & Public Space | ✓ | |

| Access to Recreation Facilities | ✓ | |

| Visitability and Universal Design | ✓ | |

| Tree-Line and Shaded Streetscapes | ✓ | |

| Green Infrastructure and Buildings (31 points) | Prerequisites: Certified green building, Minimum building energy performance, Indoor water use reduction, Construction activity pollution prevention | ✓ |

| Outdoor Water Use Reduction | Use of fountains | |

| Building Reuse | Pork processing plants were demolished | |

| Historic Resource Preservation and Adaptive Reuse | Pork processing plants were demolished | |

| Minimized Site Disturbance | Entire site needed decontamination process | |

| Rainwater Management | ✓ | |

| Heat Island Reduction | ✓ | |

| Renewable Energy Production | ✓ | |

| District Heating and Cooling | ✓ | |

| Wastewater Management | ✓ | |

| Recycled and Reused Infrastructure | Entire site needed decontamination process, railways/roadways were not reused | |

| Light Pollution Reduction | ✓ |

United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

| UN SDG | UN SDG Target | Project Performance |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages | 3.3: By 2030, end epidemics and communicable diseases 3.9: By 2030, substantially reduce number of deaths + illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water and soil pollution and contamination | Promotes walking/biking paths + outdoor activity Barrier-free multi-use pathways and trails welcome and entice visitors to explore this urban green space |

| SDG 7: Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all | 7.3: By 2030, double the global rate of improvement in energy efficiency | Utility sources are all in the pavilion – passive systems: solar panels on south side of pavilion (onsite power needs) Stormwater management systems collect 100% of rainfall for irrigation |

| SDG 11: Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable | 11.4: Strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage11.5: Reduce the adverse effects of natural disasters11.7: Provide access to safe and inclusive green and public spaces | Corktown Commons grounds protect city against flooding Park is seen as a neighbourhood amenity for all |

| SDG 15: Life on land | 15.1: By 2020, ensure the conservation, restoration and sustainable use of terrestrial + inland freshwater ecosystems and their services, in particular forests, wetlands, mountains and drylands, in line with obligations under international agreements | Native species of plants are planted to promote local propagation and benefit wildlife in the region |

To conclude, the Corktown Commons Park is rich in both ecological history and cultural history, and although the flora and fauna of the site has been gracefully restored, the cultural associations of the site and those who played a large role in its present significance are less acknowledged on site. This includes both the industrialists from the nineteenth century and the Indigenous groups that cared for and lived off the lands. While plaques and online resources are available for these narratives, the new ecological landscape is one that seems to hold priority.

Works Cited

- Bredin, Simon. “Winning Designs Revealed for Major Indigenous Public Artworks.” Winning Designs Revealed for Major Indigenous Public Artworks | Waterfront Toronto, Waterfront Toronto, 27AD, .

- Byrne, Denis and Gro Birgit Ween. 2015. “Bridging Cultural and Natural Heritage.” pp.94-111. In Meskell, Global Heritage: A Reader. Wiley Blackwell.

- City of Toronto. “Next Phase of Waterfront Revitalization.” Public And Stakeholder Engagement Summary June 2022, City of Toronto, June 2022, .

- Dowers, Tennille, and Meghan Hogan. “From the Archives: Corktown Common.” Waterfront Toronto, WATERFRONToronto, 9 Aug. 2016.

- “History.” The Don River Valley Park, Evergreen.

- “History of the Port Lands.” Waterfront Toronto, 25 Sept. 2019.

- Landscape Architecture Foundation. “Corktown Common.” Landscape Performance Series, JJR Roy Fund, 23 July 2018.

- Laura Solano; FROM WASTELAND TO PARKLAND: THE MAKING OF CORKTOWN COMMON. Journal of Green Building 1 November 2017; 12 (4): 109–140.

- Lemos, Carolina. “Book: Corktown History Toronto.” Corktown History, The Corktown News, 18 Feb. 2022.

- Palmer, Luc. “A Critique of the Planting Design of Corktown Common Based on Principles of Ecologically-Informed Plant Communities in the Urban Core.” Academia.edu, 19 Jan. 2022, .

- Randall, MCFC. “William Davies Co…” As I Walk Toronto, WordPress, 9 Aug. 2014.

- Richardson, A. H. “Don Valley Conservation Report, 1950.” Digital Archive @ McMaster University Library, 1950.

- Stinson, Jeffery. The Heritage of the Port Industrial District. Vol. 1. Toronto: Toronto Harbour Commissioners, 1990.

- “Toronto Pork Packing Plant.” Lost Rivers.

- WATERFRONToronto. “Waterfront Toronto.” Corktown Common Fact Sheet, .

- “West Don Lands.” West Don Lands | Waterfront Toronto, Waterfront Toronto, .

- Zhang, Zenan. “Landscape Infrastructure Works as Catalyst in Urban Design: A Case Study Exploration of the Corktown Common Park in West Don Lands, Toronto.” Landscape Infrastructure Works as Catalyst in Urban Design: A Case Study Exploration of The Corktown Common Park in West Don Lands, Toronto, University of Guelph, 2 May 2014.

Banner image: Restored wetland in Corktown Commons Park, Susan Ross, 2018.