Case study prepared by Patrick Forster, Carleton University

ESCARPMENT USE & POPULATION GROWTH: ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL SUSTAINABILITY POLICIES WITHIN THE NIAGARA ESCARPMENT

Keywords: Population Growth, Niagara Escarpment Biosphere, Land Use, Environmental Conservation

Presentation: The following slide presentation was presented on Nov, 21st 2017 in conjunction with the information supplied in this Case Study. It is meant to be a visual aid to help support the information provided.

Lessons Learned: Many different acts and regulations have been put in place, as per UNESCO’s recommendation, to help secure areas of natural heritage such as the Niagara Escarpment, but unfortunately, “As with many such natural features, the resource planning and management strategies developed tend to be based upon the present-day situation rather than upon a recognition of the changing and evolving nature of the feature.” Page, R. (2003). Despite this many of the results given from the Performance Indicators for the Greenbelt Plan showed a small trend towards improvement, with the rate of lot fragmentation only “increasing by a small 0.7% and lot creation mostly tending to increase inside settlement areas of the Niagara Escarpment” Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing (2015). The site of the Niagara Escarpment Biosphere shows a trend towards improving the way it conserves its natural beauty and traditional uses, however it is hard to determine if such protective initiatives that are currently enacted provide a realistic interpretation of progress or regression. The Escarpment is such a wide expanse of land it reacts slowly to change, as do the people who live on it. The reason behind a biosphere is to ensure the integration of all the living things within its boundaries, both naturally made and human constructed such as social and economic factors. However there is an argument that there hasn’t been enough time for the Escarpment to react, as most of the more progressive policies having been brought into effect were done in the early 2000’s. The results of continued growth nevertheless are still easy to conclude, if population growth continues to expand into the site large parts are almost guaranteed to be lost under urban development and with those pieces a large part of the regions biodiversity.

Description: For the purposes of this Case Study the focus will be centered on the Canadian portion of the Niagara Escarpment that has been designated as a World Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO. The Niagara Escarpment (NE) is the dominant landscape feature of Southern Ontario, stretching 725 km from Lake Ontario to the tip of the Bruce Peninsula. According to UNESCO. (2015) “The biosphere reserve includes the greatest topographic variability in southern Ontario, with habitats ranging over more than 430 m in elevations and including Great Lakes coastlines, cliff edges, talus slopes, wetlands, woodlands, limestone alvar pavements, oak savannahs, conifer swamps and many others. These habitats collectively boast the highest level of species diversity among Canadian biosphere reserves, including more than 300 bird species, 55 mammals, 36 reptiles and amphibians, 90 fish and 100 varieties of special interest flora.” Because of its distinctive geology and ecology the Escarpment has become a significant focus for research and protection efforts.

The Niagara Escarpment on the Bruce Peninsula, thebrucepeninsula.com

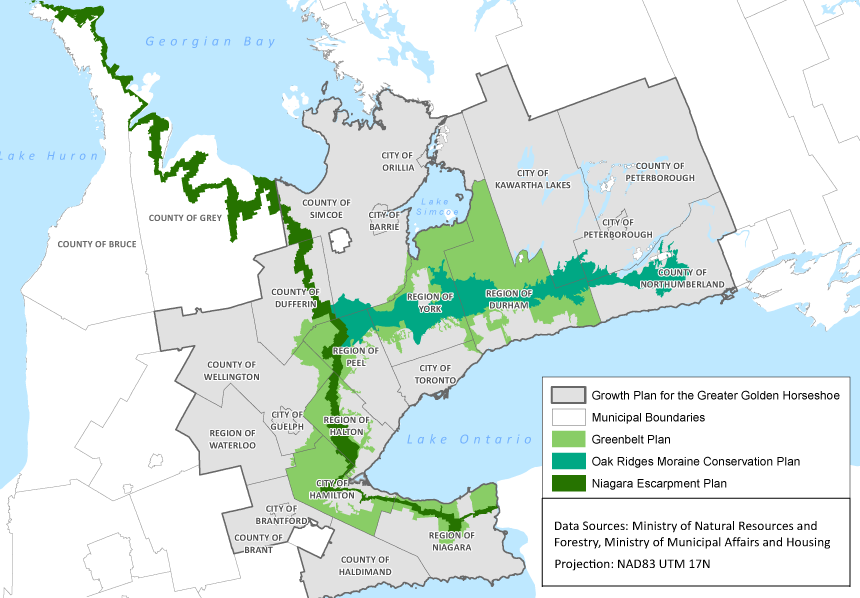

Because of its size the Escarpment falls under the jurisdiction of a number of different municipalities. Each of these municipalities face pressures for development of the Niagara Escarpment, as the Niagara Escarpment Commission (2017) understands it “these pressures mainly coming from the ever increasing needs of population growth in southern Ontario along with the needs for construction materials, residential expansion and provision of access to recreation spaces.” The amount of interests, political, scientific, and economic, have made the government at the provincial level put a number of regulations into place concerning the land use and then enforce these regulations through regional municipalities.

The purpose of this case study is to evaluate the degree of effect that population growth, and by association urban growth, has had on the conservation effort of the Niagara Escarpment Biosphere Reserve. Furthermore the goal is to determine if the implementations of Policies or Acts have been able to preserve both the natural and cultural heritage of the Escarpment. By determining whether the pieces of legislature that have been aimed at preserving the boundaries of the biosphere reserve have been successful we can come to understand if the goals of preserving the Niagara Escarpment have been supplanted by the needs of the population .

Niagara Escarpment Biosphere, Niagara Escarpment Commission 2006

Timeline

· 1963-1967, The creation of the Bruce Trail along the length Niagara Escarpment led to public recognition of the Escarpment as an area of scenic beauty, biological value, and highly sensitive nature. “The Bruce Trail Association believed increased use of the NE would build landscape value and lead to its protection.” Whitelaw, G. & Eagles, P. & B. Gibson, P. (2008).

· 1967 The ‘Niagara Escarpment Conservation and Recreation Report, a wide-ranging study of the Escarpment, with a view to preserving its entire length. Whitelaw, G. & Eagles, P. & B. Gibson, P. (2008).

· 1971 the formation of the Niagara Escarpment Inter-Ministerial Task Force, to consider an overall comprehensive policy for the Escarpment. “The Task Force carried out public consultation but did not engage in any collaborative processes. The Task Force recommended a provincial planning system featuring strong land-use regulation of private land and public ownership of small portions.” Heidenreich, C. (1987)

· In 1973, the Niagara Escarpment Planning and Development Act was passed by the government of the Province of Ontario. “This Act established the Niagara Escarpment Commission (NEC) which published its Proposed Plan for the Niagara Escarpment in 1979.” · Moss, M., Milne, R. (1998, pg 252).

· 1985, the Niagara Escarpment Plan was approved

· In 1990 the Niagara Escarpment was designated a World Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO, “intended as a demonstration area for both the conservation of biological diversity and the promotion of environmentally appropriate development.” Moss, M., Milne, R. (1998, pg 252).

· 2003, instigation of the Ontario Planning Act which gives municipalities the ability to implement through official plans, secondary plans, plans of subdivision, and by-laws under the guidance of the Provincial Policy Statement.

· 2005, The Greenbelt Act, enables the creation of a Greenbelt Plan to protect about 1.8 million acres of environmentally sensitive and agricultural land in the Golden Horseshoe from urban development and sprawl. It includes and builds on about 800,000 acres of land within the Niagara Escarpment Plan and the Oak Ridges Moraine Conservation Plan.

Stakeholders

- UNESCO: UNESCO is responsible for coordinating international cooperation in education, science, culture and communication. This organisation was responsible for designating the Niagara Escarpment as a World Biosphere Reserve. “For UNESCO the Escarpment represents nationally and internationally significant landforms that include representative and scientifically valuable examples of sustainable relationships between human activities and ecosystems.” Niagara Escarpment Commission (2017). In order to protect the biosphere UNESCO gives recommendations on policies the state they are dealing with should take.

- Niagara Escarpment Commission: The NEC is a statutory body that operates at “arm’s length” from the provincial government in accordance with the Niagara Escarpment Planning and Development Act and the Agency Establishment and Accountability Directive under the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry. “The NEC is mandated to develop, interpret and apply policies that maintain and enhance the vitality of the Escarpment’s unique environmental and landscape features. Its decisions are made independently, impartially, and according to a risk management framework. The Niagara Escarpment Commission acts as the central convener of the Niagara Escarpment Biosphere Reserve.”

- Municipalities inside the Niagara Escarpment: It is the role of the local municipalities according to the Ontario Planning and Development Act and Places to Grow Act to expand and develop their communities. Because of their location in the Niagara Escarpment this means that they will have to develop inside protected lands. It is the municipality’s responsibility to grow in such a way as to minimalize their effect on the local environment.

- Local Residents and Community Groups: The people who could be argued to have the most stakes in the Escarpment are the people who live and work there. The Escarpment is a setting of various different lifestyles, from rural, to townships, and in some cases off grid living. These people work live and play here, creating communities and groups that form the base of many of the advocacy groups that look to protect the natural setting of their homes from over urbanisation.

- Indigenous Stakeholders: A subsection of the local resident would be those who have native ties to the area. The Niagara Escarpment is the traditional home for a multitude of indigenous tribes that include the Algonquin, Iroquois, and the Métis. These people have a stake in the future of the lands use as they consist of traditional hunting grounds and sacred spaces. To this day there remain some indigenous groups who continue to provide stewardship to their land located on the escarpment.

- Ontario Municipal Board (OMB): The OMB is an independent administrative board that is responsible for hearing appeals and deciding on a variety of contentious municipal matters. The OMB has a major role in dealing with land use planning matters under the Planning Act. Its main role in community planning as per the Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing (2017) is to hold public hearings on:

- land use planning applications, such as subdivisions, land severances and minor variances; and,

- planning documents and applications, such as official plans and zoning by-laws. As the OMB is the primary source for appealing land use designation it is constantly used by those looking to develop areas inside the Niagara Escarpment.

- Parks Canada: Within the borders of the Niagara Escarpment lie two national parks, the Bruce Peninsula National Park and the Fathom Five National Marine Park. These parks both maintain local natural heritage and provide places to teach guests about the Canadian wilderness and wildlife their parks contain.

Natural heritage: The Natural Heritage that composes the Niagara Escarpment is as vast as the escarpment itself and has been documented by the Niagara Escarpment Commission Much of the natural Heritage is visible upon first inspection of the Niagara Escarpment, such as the naturally picturesque rock formations caused by the retreating glaciers and the forests that have taken up root there.

Going into greater detail, the northern portion of the Niagara Escarpment falls within the Great Lakes- St. Lawrence Forest Region, while the southern portion of the Escarpment falls within another biome that is classified as a Deciduous Forest Region. The breadth of this protected biosphere is so great that a number of “Tree species found along the Escarpment vary depending on geographic location, soil type and moisture. Although most of these forests were cleared during human settlement, with careful management many areas will mature back to an “old growth” state.” Niagara Escarpment Commission (2017). The flora and fauna of the southern portion of the Niagara Escarpment represent the most diverse stock in an identified region within Canada, which is precisely the reason as to why it was designated a biosphere by UNESCO in the first place.

As described by the Niagara Escarpment Commission (2017), the Niagara Escarpment supports a number of rare habitat types that are critical for biodiversity conservation. These include the following:

- Ancient Cedar Forest: The cliffs of the Niagara Escarpment support an ancient forest consisting of stunted eastern white cedar with individuals exceeding 1,000 years old. Fallen cedar logs at the base of Escarpment cliffs can persist over 3,000 years, with even older specimens found in upright positions on rocky ledges along Georgian Bay.

- Tallgrass Prairie: Remnants of tallgrass prairie can be found in the Hamilton and Niagara regions of the Escarpment. These globally imperiled vegetation communities need fire to persist and support a wide range of plant, bird and insect species. Typical plant species found in prairies include big bluestem, little bluestem and Indian grass.

- Alvar: Alvars are globally rare habitats that consist of limestone pavement with minimal soil coverage. Some of the best examples of alvars in the world are found along the northern Bruce Peninsula. Alvars support many unique and rare species, including Lakeside Daisy (threatened) and the Eastern Loggerhead Shrike (endangered). Plants that survive on these rock barrens are adapted to extreme conditions.

Cultural heritage: For as long as there have been people in Canada they have been using the Escarpment in one way or another. The northern part of the Escarpment that separates Lake Huron and the Georgian Bay has a long tradition of being used by the Algonquin tribes for “hunting, fishing, and gathering and is a part of their traditional lands. In addition to the Algonquin’s, Iroquoians also had a presence on the upper regions of the escarpment in the County of Simcoe.” Heidenreich, C. (1987). The region of the Escarpment has become a diverse place where many different cultures, especially those of native and European descent, have had the time to both accumulate and mix together providing an excellent sample of a combined cultural landscape.

“These resources need to be protected over the long term to ensure that the connection to our shared past is maintained and that quality of life is not diminished as growth takes place. First Nations and Métis people in Ontario have a unique relationship with the land and its resources and this relationship continues to be of central importance to First Nation and Métis communities in the area of the Niagara Escarpment today. Ontario, including the area covered by the Niagara Escarpment Plan Area, is largely covered by a number of Treaties which provide for treaty rights.” Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (2017, pg 1).

But not all the Cultural Heritage of the area is specifically related to the indigenous peoples who used to live there. Over the years, as other people began to settle on the Escarpment, they brought their own uses to the land. Much of the Niagara Escarpment has been used as agricultural farmland for generations, with many of the families that first settled there having built their homes and communities. With the hundreds of little townships that dot the escarpment each has its own history and significance to the people that live there.

Escarpment and Vineyard, Don Alexander

Environmental sustainability: If left untended, the particular combination of geological and ecological features along the Niagara Escarpment results in a landscape that creates its own sustainability features. “The natural areas found across the Niagara Escarpment act to clean the air, provide drinking water and support recreational activities that benefit public health and overall quality of life, as well as helping to address and mitigate the effects of climate change.” Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (2017, pg 1). However, as the Escarpment isn’t left to be as it is, it faces a challenge that threatens to destroy its biodiversity, and that is fragmentation. The subdivision of land lots shrinks animal habitats and causes these habitats to become isolated. “Patch isolation is associated with decreases in biodiversity in a wide range of ecological systems.” Moss, M., Milne, R. (1998, pg 251).

Social sustainability: Steps for providing a sustainable growth have already been thought out by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (2017, pg 2). They rationalise under the Greenbelt Plan that “locations are identified where urbanization should not occur in order to provide permanent protection of the agricultural land and the ecological features and functions occurring in the Greenbelt Plan Area, which includes the Niagara Escarpment Plan Area, as well as the Oak Ridges Moraine Conservation Plan Area, and the Protected Countryside of the Greenbelt Plan. The Niagara Escarpment Plan, the Oak Ridges Moraine Conservation Plan and the Greenbelt Plan work within the framework set out by the Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe for where and how future population and employment growth should be accommodated. Together, all four provincial plans build on the Provincial Policy Statement to establish a land use planning framework for the Greater Golden Horseshoe and the Greenbelt Plan Area that supports a thriving economy, a clean and healthy environment and social equity.” It is through these successively linked policies and plans that they believe they can responsibly control the consistently growing social environment inside the Niagara Escarpment.

Cultural sustainability: Much of what is in the Greenbelt Plan, and the Niagara Escarpment Plan focuses only on the culture of farming that is present in the Escarpment “the intended effect of managing growth, protecting agricultural lands and the natural environment, reducing greenhouse gas emissions and supporting economic development in the agricultural sector.” Reusser, M. (2015). While this is well and good, providing a continuity of farming practices within the escarpment, there is a lack of focus on what else makes up the culture of the escarpment and ways to ensure that stability as it should. “A biosphere reserve seeks to harmonize and reconcile the great dichotomies of modern existence: past and present, nature and humanity, science and values. …More particularly, biosphere reserves represent for… a new stage in the ethical and religious history of humankind. They are ‘sacred spaces’ in human culture, perceived to be centres of extraordinary power and reality. Such a space is not mere space but fully a place, imbued with a ‘sense of place’” UNESCO MAB Secretariat (2001). To reach a fully sustainable culture within the Escarpment and be more in line with UNESCO’s ideals more emphasis needs to be put on protecting and enhancing the lesser judged groups present.

Economic sustainability: Much of what constitutes the policies and acts regarding the Niagara Escarpment are provisional for the development and sustainability of the food sector, as this is the area’s biggest export. The

“agricultural System for the Greater Golden Horseshoe which aims to protect a continuous productive agricultural land base and a complementary agri-food network that together enable the agri-food sector to thrive. An Agricultural System has two components: the agricultural land base and the agri-food network. The agricultural land base is comprised of prime agricultural areas including specialty crop areas, as well as rural lands where active agricultural and related activities are ongoing. The agri-food network includes infrastructure, services and agri-food assets important to the viability of the sector.” Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry. (2017, pg 3).

Keeping in line with these ideals in regards to the infrastructure supporting the Escarpment food industry, in essence provides the support needed to keep economic activity going in the food sector that is at home in the area.

Measurement: Under the General Conference of the UNESCO meeting in Paris from 17 October to 21 November 1972, natural protection and international protection of the cultural and natural heritage of a location is given a list of requirements that need to be met to ensure that effective and active measures are taken for the protection, conservation and presentation of the cultural and natural heritage situated on its territory. The UNESCO (2017) Convention states that each State Party to this Convention shall endeavor, in so far as possible, and as appropriate for each country:

- to adopt a general policy which aims to give the cultural and natural heritage a function in the life of the community and to integrate the protection of that heritage into comprehensive planning programmes;

- to set up within its territories, where such services do not exist, one or more services for the protection, conservation and presentation of the cultural and natural heritage with an appropriate staff and possessing the means to discharge their functions;

- to develop scientific and technical studies and research and to work out such operating methods as will make the State capable of counteracting the dangers that threaten its cultural or natural heritage;

- to take the appropriate legal, scientific, technical, administrative and financial measures necessary for the identification, protection, conservation, presentation and rehabilitation of this heritage; and

- to foster the establishment or development of national or regional centres for training in the protection, conservation and presentation of the cultural and natural heritage and to encourage scientific research in this field.

Determining if these measures are in effect is a good way to measure how much is being done to by the government to establish conservation efforts. In the case of the Niagara Escarpment both policies and organisations have been set up to protect the natural heritage of the escarpment, and conduct scientific studies, most of which is done under the Niagara Escarpment Commission.

To determine if the polices developed for the Niagara Escarpment are being carried out by the Performance Indicators described by the Greenbelt Plan, to ensure the protection of the natural environment, the Niagara Escarpment Commission tasked the Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing (2015) to draft a set of guides that would prove the success of policies made under UNESCO’s recommendations. The following selection of indicators most relevant to the Niagara Escarpment determine if the Protected Countryside policies, Greenbelt Plan, Oak Ridges Moraine Conservation Plan and Niagara Escarpment Plan were having any effect on conservation efforts within the Greenbelt, all of which have an effect on the Niagara Escarpment.

- The growth in lots one acre and greater created outside settlement areas between 2007-2014.

- The growth in dwelling units created outside settlement areas from 2001-2006 compared to 2006- 2011 in the Greenbelt.

- The percentage of PC, ORMCP and NEP covered by woodlands in 2000-2002 as a baseline number, to compare with future data.

- The percentage of the PC policies, ORMCP and NEP covered by mapped wetlands in 2000-2002 as a baseline number, which may be compared with future data. This indicator includes all wetlands mapped by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (MNRF). It includes wetlands evaluated or confirmed by MNRF in accordance with the Ontario Wetland Evaluation System (OWES) or wetlands identified through mapping.

In these chosen indicators we see how it is that the Niagara Escarpments success is measured. This is primarily done from an environmental standpoint, with the measuring of woodland and wetland areas. Higher percentages of these natural landscapes with lower reduction rates are the degree by which their success is accounted. There is also an eye on social growth as well, primarily because this is the primary threat to the biosphere as a whole. These indicators also take into account the human factor, mostly by looking at the quantity of smaller lots, which are a cause of land fragmentation, and the rate of dwellings created outside urban zones. Measuring where people settle is critical to the understanding of the treatment of the Niagara Escarpment. People have the largest impact on the environment they inhabit, as the more they build, either inside or outside of urban zones, will cause the loss of the woodlands and wetlands these policies are trying to protect.

References

Books/Book chapters/Journal articles

- Heidenreich, C. (1987). Se lements and Missionaries, 1615-1650. In From the Beginnings to 1800. Historical Atlas of Canada, 1.

- Moss, M. R., Milne, R. J. (1998). Biophysical processes and bioregional planning: The niagara escarpment of southern ontario, canada. Landscape and Urban Planning, 40(4), 251-252. doi:10.1016/S0169-2046(97)00116-3

- Whitelaw, G. & Eagles, P. & B. Gibson, Philadelphia: (2008). Roles of environmental movement organisations in land-use planning: Case studies of the Niagara Escarpment and Oak Ridges Moraine, Ontario, Canada. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management. 51. pg 806.

- Page, R. E. (2003). Effects of land-use patterns and land ownership on biodiversity in the natural areas of the niagara escarpment world biosphere reserve (Order No. MQ82892). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (305325414). Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.

Policies and reports

- Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing. (2015) Performance Indicators for the Greenbelt Plan. Queen’s Printer for Ontario. Part 1.

- Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry. (2017) Niagara Escarpment Plan. Queen’s Printer for Ontario. pg 1-3, Retrieved from: https://files.ontario.ca/appendix_-_niagara_escarpment_plan_2017_-_oc-10262017.pdf

- UNESCO (1972) The General Conference of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization meeting in Paris from 17 October to 21 November 1972, at its seventeenth session, Retrieved from : http://whc.unesco.org/en/conventiontext/

- UNESCO MAB Secretariat. (2001). Biosphere Reserves: Special Places for People and Nature. Paris: UNESCO. Pg 36

Websites

- Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing. (2017). Ontario Municipal Board. Retrieved November 11, 2017, from http://www.mah.gov.on.ca/Page1755.aspx

- Niagara Escarpment Commission. (2017). Ecology. Retrieved November 10, 2017, from https://www.escarpment.org/NiagaraEscarpment/Environment/Ecology

- Reusser, M. (2015). Land use plans must put farmland first. Retrieved November 10, 2017, from https://ofa.on.ca/media/news/land-use-plans-must-put-farmland-first

- UNESCO. (2015) Niagara Escarpment. Retrieved November 11, 2017, from http://www.unesco.org/new/en/natural-sciences/environment/ecological-sciences/biosphere-reserves/europe-north-america/canada/niagara-escarpment