Case Study prepared by Amanda Prevost, Carleton University

The Integration of Affordable Housing in Historic District Conservation “Mole Hill Housing” (Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada)

KEYWORDS Social Sustainability, Eco-friendly Housing, Affordable Housing, Community Gardens, Geothermal Energy, Waste Management

POWERPOINT Case Study Presentation

LESSONS LEARNED There is so much to be learned from the Mole Hill Housing project. This case study was conducted gathering research from over a dozen sources. The reason for this is the lack of information, in a central location to fully appreciate the depth of the project. Nonetheless, the Mole Hill Housing project is a leading example of a heritage district that addresses environmental sustainability, economic sustainability and cultural sustainability. While the project meets success in all of those categories, there is a lack of research done that assesses recent facts of continued success, ten years after the project was completed. This project is the first district to implement many of its characteristics, the project has deep rooted history, and it is very unique to the area. Other projects can learn from this project, and how the City or large organizations can work with a community and its members together, rather than against one other, which occurred during steps of this project. Mole Hill is a fantastic example overall, how all Canadian cities can incorporate densification, increase of community gardens and community operated housing.

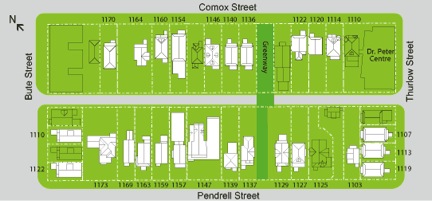

DESCRIPTION Mole Hill Housing is located in the city of Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. According to the Mole Hill Community Housing Society (2013), the Mole Hill district consists of all of the properties located between the streets of Pendrell and Comox, and Thurlow and Bute Street. There is no street located between the two blocks, but rather a community green laneway. This lane way goes both horizontally and vertically through the district. Looking at the Vancouver Heritage Register (2014), all of the properties located within this space are on the register as having heritage value, but are not legally designated. The property addresses are Pendrell Street (1103, 1125, 1127, 1129, 1137, 1139, 1147, 1157, 1159, 1163, 1169, 1173), Comox Street (1110, 1114, 1120, 1122, 1136, 1140, 1146, 1154, 1160, 1164, 1170), Bute Street (1110, 1122) and Thurlow Street (1107, 1113, 1119).

Site map (Mole Hill Community Housing)

Site map (Mole Hill Community Housing)

TIMELINE In a report put together by Donald Luxton and Associates Inc. (2012), the Mole Hill district was “built between 1888 and 1904” and has fought demolition for several years. As stated, the area holds value due to its age, and the lack of other neighbourhoods in the West End Vancouver “surviving… pre-World War One” (Luxton, 2012 p. 2). This historic district was among those built in “the first two decades of the growth of the city of Vancouver” (Luxton, 2012 p. 2). The use of the area was residential homes; the location was situated close enough to downtown, which held jobs and industrial activity. As the economy subsequently dropped in later years, the housing was modified into “lodging rooms” and “many [units] received additions” in order to occupy more tenants (Luxton, 2012, p. 7). The area has fought demolition due to city standards and “zoning changes that permitted high-rise construction” following the 1950s (Luxton, 2012, p. 7). A section of the homes in the surrounding area of today’s Mole Hill historic community “were torn down in the 1970s, in anticipation for a traffic couplet” (Luxton, 2012, p. 7). A significant reason why the remaining housing has been kept is due to the areas high level of densification, and the Mole Hill district contributes to the city’s limited green space. During the late 1980s and early 1990s, the city of Vancouver sought to demolish the area, as the “city-owned rental units sat vacant” (Luxton, 2012, p. 7). This was later changed, as members of the Vancouver community “formed the Mole Hill Living Heritage Society” and fought for its protection (Luxton, 2012, p. 8). According to the Mole Hill Community Housing Society webpage, work began in 1999, in phase one of the rehabilitation, fixing seventy (70) units “with completion in 2002” (Mole Hill Community Housing Society, 2013). Phase two commenced immediately afterward and an additional one hundred (100) suites were completed by 2003 (Mole Hill Community Housing Society, 2013).

STAKEHOLDERS

- Owners and Occupant: The Mole Hill district is owned by the City of Vancouver, and is currently leased to the Mole Hole Community Housing Society on a sixty (60) year, no cost, agreement. There are 170 units available, which are designated for low-income families, seniors and couples (Ground Oriented, Medium Density Housing GOMDH, 2003).Although many of the units were vacant, as stated by Donald Luxton’s report (2012), the tenants that did occupy the remaining units were protected, as phase one units were reserved for their return.

- Designers and Builders: In order to upgrade the historic district to its original form in the best way possible, “McEwan in association with Hotson Bakker Boniface Haden Architects took on the complicated task of restoring heritage craftsmanship while meeting today’s standards” (Mah, 2004). These designers worked with several groups such as “the Community Development Unit of the Provincial Ministry of Community Development, the Samuel and Saidye Bronfman Foundation, the Vancouver Foundation, the Co-operators Community Economic Development, and the VanCity Community Fund” preparing and achieving all of the goals set for the community (Mah, 2004). The diverse knowledge from each group allowed for the district to incorporate heritage values, new technology, and environmental sustainability all into the one project (Mole Hill Community Housing Society, 2013).

- Authorities: As the Province of British Columbia, and the City of Vancouver provided the funding for the project, the historic district was planned and managed by the two levels of government. The structures were brought up to building codes, a mandatory action under the province (Mole Hill Community Housing Society, 2013).

- Communities of Interest: There are several groups and organizations that made this project possible, from designing to funding, to achieve the best possible outcome for the environment and the community. The Mole Hill Community Housing Society was created by members of the Vancouver community, and continues to be run in the same manor. It is with this Society, the City of Vancouver, and BC Housing that multiple communities of interest were able to work together. The organizations that maintain the cultural framework of the historic district include “the Community Development Unit of the Provincial Ministry of Community Development, Cooperatives and Volunteers, the Samuel and Saidye Bronfman Foundation, the Vancouver Foundation, the Co-operators Community Economic Development Fund and the VanCity Community Fund” (GOMDH) 2003, p. 3). Other organizations such as “City of Vancouver, the Vancouver Coastal Health Authority, British Columbia Ministry of Health, BC Housing and the Dr. Peter AIDS Foundation “put the “Dr. Peter Center Project” together in order to support the AID/HIV patients living in the community (Mole Hill Community Housing Society, 2013). There are a few other programs, such as Watson House to support “young people with mental health issues,” and the Heart House Society “which provides temporary housing… for on-locals recovering from heart surgery,” and a YMCA Daycare which supports families (Mole Hill Community Housing Society, 2013).

NATURAL-CULTURAL HERITAGE After reviewing the City of Vancouver’s webpage, none of the addresses located within the boundaries are designated a heritage sites. While they still hold value under the Vancouver Heritage Register (2014), they do not have the legal designation to be protected to the fullest extent. This means work can be done on the property by individuals, without a permit (Vancouver Heritage Register, 2014, p. 4). Under the Vancouver Heritage Register, all of the properties are labeled in value in a system of “A, B or C.” They are ranked by “primary significance – A” which entails the best example of a type of architecture, or may have historical significance to a person, “B- Significance” in which the property is a “good example of a particular style” or may have “documented historical or cultural significance” and the category “C – contextual or Character” which can include groups of buildings or relation to a particular person (Vancouver Heritage Register, 2014, p. 4). All of the properties within the Mole Hill Housing District fall within one of the “A, B or C” categories (Vancouver Heritage Registration, 2014).

HERITAGE VALUE According to Heritage Canada Foundation (2004), the area situated in the Mole Hill Community is the “city’s only intact Victoria and Edwardian neighbourhood” and the housing dates back to the late 1800s. Going into detail, under the Journal of Commerce, Cheryl Mah explains the work conducted in the interior of the homes in order to revert the structure into their original frameworks. Aspects such as “trims, fireplace fronts, mantles and wood floors” were all renovated, keeping the character-defining elements. Details of the exterior, such as types of paint were matched to the original as best as possible. Any new features that needed to be added to the structure were built in the rear of all of the houses, in order to not change the appearance of the communities character-defining elements (Mah, 2004).

SUSTAINABILITY

- Environmental Sustainability: There are two main categories in which the Mole Hill project includes environmentally sustainable decisions and plans. The first category is environmental technology that improves or aides in creating a better system for the environment. This includes, “the use of geothermal energy,” the adaptive reuse of “60-70% of the original materials” for the renovation of the structure to minimalized “construction waste.” The project also has “increased energy efficient technology, and the use of a “water feature using storm-water” (Open Green Building Society, 2013). Environmentally friendly features, that must be maintained on a daily basis by the community collectively, in order to succeed, fall into the second category. This includes the community greenway, and gardens that hold different plant species such as fruit trees to feed the community, and the upkeep of the trees persevered for being 90 per cent mature. There is a preference to pedestrians in the historic district, and it is encouragement that tenants do not own a car. There is a partnership established with “CAN-partnership to reduce vehicle ownership” and provide a limited amount of vehicles for the community to share. (Open Green Building Society, 2013). With this came the creation of a storage unit that supports “168 bicycles” (Open Green Building Society, 2013).

- Socio-Economic Sustainability: The Mole Hill Housing project, has been economically sustainable in a variety of ways. The members of the Mole Hill community are able to maintain their lifestyles through the subsidized homes. The housing is sixty (60) per cent paid for through the government, leaving only forty (40) percent of rent left to the tenants to pay. Accommodations are made for tenants that cannot afford this (Open Green Building Society, 2013). The project is also economically sustainable as “it seamlessly integrates food production within the transformation of individual house lots into communal green space” (The Carrot City Initiative, 2014). To add to this point on agriculture, the Society runs a Farmer’s Market in the summer, where local goods can be purchased. Members of the community with AIDS, and needing extended support are provided meals on a regular basis (Mole Hill Community Housing Society, 2014). The district tries to run on little funding, and attempts to find resources for free. Most of the work needed to maintain the property is completed on a volunteer based by the tenants currently residing in the Mole Hill district, eliminating the cost of hiring outside sources (Mole Hill Newsletter, May 2014).

- Socio-Cultural Sustainability: There are two ways in which this project shows socio-cultural sustainability. One way is within the community members, and one is beyond the tenants of Mole Hill. The Society of Mole Hill attempts to create gatherings on a regular basis for the community tenants to participate in. As advertised, this includes events such as barbeques held in shared spaces. The events are family friendly and open to all (Mole Hill Newsletter May 2014). Beyond special event the district is designed on community space, to promote interaction amongst tenants. As described by The Carrot City Initiative, 2014, “The pedestrian-priority open-space design features a greenway in the lane behind the houses. This “living lane” provides a pedestrian-friendly space for the surrounding community to gather. The lane also features community-garden plots, and a community-oriented laundry room, workshop, refuse and recycling area.” This is ideal for the adult tenants, and the YMCA daycare provides space for the children to interact. Mole Hill tries to get members of the larger Vancouver area to participate in its ongoing project. The project is a leading example of heritage conservation and serves as an educational tool for environmental sustainability, having many internal programs for the community to get involved and volunteer for (Mole Hill Community Housing Society, 2014).

FUTURE As examined in a report by Betty Baxter, published under the Community Housing Society, the accomplishments achieved for the Mole Hill project, and community’s plans for the future of Mole Hill are analyzed. Mole Hill strives to be the “greenest Non-profit housing society,” and “identify areas for green improvements” (Baker, 2013, p. 5). There are no further details as to what these plans entail, or a time frame for the work to be complete. A second goal set for the future is to “create an environmental specific mission/policy and action plan” and join “upcoming opportunities” in research and “broader environmental movements” (Baker, 2013, p. 5). The only specific plan for this property in regards to changes is the “expansion of the lane and greenway” (Baker, 2013, p. 5). It can be assumed this is to enlarge both the community space, and gardens in order to improve the social and environmental status, but it is not specified by Betty Baker.

MEASUREMENT In order to measure if the Mole Hill project has been successful or not, and in which categories, the Megan Da Silva and Jane Henderson, 2011, “Sustainability in Conservation Practice” article will be used. The categories as defined by Da Silva and Henderson, label the measurement below:

- Compliance with Regulations, Targets and Best Practice: This category is met, as the district is owned by the City of Vancouver, and in conjunction with the province of British Columbia, oversaw all steps of the project, ensuring all aspects are up to code. This includes both the building code, and making sure the project did not cause unneeded harm to the environment (Mole Hill Community Housing Society, 2013).

- Waste Management: This category is met as the construction waste was minimized by the adaptive reuse of recycled building material (Open Green Building Society, 2013). To add to this, the community has a communal recycling system for acquired material (Mole Hill Community Housing Society, 2013).

- Sustainable Procurement and Energy Management and use of other Natural Resources: This is met, as “Mole Hill is the first social housing project in North America with ground source heating. The system’s up-front costs are prohibitive, but the long-term savings in operating costs have been estimated at six to ten million over the term of the 60-year lease the City has given the co-operative.” (Grdadolnik, 2005). The “geothermal heating system in each building is sourced from one ground loop and a well planned storm water management system retains 95% of pre-existing trees and diverts rainwater into an ornamental pond rather than into the city’s storm system” (The Carrot City Initiative, 2014). This category could be critiqued however, as the Mole Hill newsletter from May 2014, stated, “For some time the effectiveness of the geothermal system has been in question. A study completed in February this year revealed that heat extraction from the geothermal fields over the last 10 years has resulted in the temperature in the fields being below the 48F required by the original design. A pilot project to address this problem will be completed over the summer.” This, and other environment elements should be revaluated, to ensure everything is working.

- Pollution Management: There is a lack of documentation, to properly state what the status of pollution management is in the Mole Hill project.

- Staff Involvement: As the Mole Hill Society runs Mole Hill, the project is maintained in relation to the staff having knowledge about environmental sustainability and making environmentally friendly decisions. Outside sources are brought in to ensure this is occurring (Mole Hill Community Housing Society, 2014). An example of this is requesting the City of Vancouver’s support “replacing 9 diseased cherry trees… with Big Leaf Maples” (Beauchamp, 2013). Without conducted research, a wise choice would not have been made by the staff of Mole Hill, to seek help and know which species to replace the cherry trees with.

- Public Involvement and Communication: This project has a ton of examples as to the community being encouraged to participate is making the Mole Hill project to be continuous environmentally friendly. This includes the encouragement to not own a car and share one, walk to needed places, contribute to the community garden, and recycle (Mole Hill Community Housing Society, 2014).

- Review of the Success of Sustainability Efforts: Well there is a touch of information that can be found of some aspect of environmental sustainability, there is a lack of documentation, for the Mole Hill project. This category is strongly underdevelopment, and is not a measurement of the project’s success.

- Actions for the Future: This category is addressed in Betty Baxter’s report with the Community Housing Society, as described above.

AWARDS

Listed on the Mole Hill Community Housing Society website (2013), the awards received for this project include:

- “City of Vancouver Heritage Award – 1996 and 2004;

- Heritage Canada Foundation & Heritage Society of BC Award – 2004;

- Canadian Construction Association, Environmental Achievement Award – 2004 (Kindred Construction);

- Vancouver Regional Construction Association Award of Excellence – 2004 (Kindred Construction);

- Canadian Society of Landscape Architects Award – 2005 (Durante Kureuk);

- Royal Architect Institute of Canada (RAIC) National Urban Design Award, Community Improvement Projects – 2006 (Hotson Bakker and Sean McEwen)

- Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation Award for Best Practices in Affordable Housing – 2006

- Architect Institute of BC, Lt. Governor of BC, Special Jury Award – 2007 (Hotson Bakker, Sean McEwen, Sandra Korpan)

- Smart Growth Project of the Year in BC – 2007”

SOURCES

- Baxter, Betty (2013). “Strategic Intent Document 2010-2015,” Mole Hill Community Housing Society, pp. 1-15. Retrieved from: http://www.mole-hill.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/Mole-Hill-Strategic-Plan-2010-15.pdf

- Beauchamp, Margot. (2013) “Mole Hill Press Release,” Mole Hill Community Housing Society, 1. Retrieved from: http://heritagevancouver.org/pdf_letters/letter-Mole-Hill-trees-2013-02-08.pdf

- Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. (2006) “Innovative B.C Partnership Revitalizes Vancouver Heritage Community from the Inside Out,” Housing Awards, Government of Canada, p. 1. Retrieved from: http://www.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/en/inpr/afhoce/afhoce/tore/hoawpr/upload/111824_3.pdf

- The Carrot City Initiative (2014) “Mole Hill,” Ryerson University. Retrieved from: http://www.ryerson.ca/carrotcity/board_pages/housing/mole_hill.html

- City of Vancouver. (2012) “Protecting Heritage Sites Through Legal Designation,” Heritage Designation. Retrieved from: http://vancouver.ca/home-property-development/heritage-designation.aspx

- Da Silva, Megan and Jane Henderson, 2011, “Sustainability in Conservation Practice,” Journal of the Institute of Conservation, 34.1, pp. 5-15.

- Donald Luxton and Associates. (2012). Mole Hill Statement of Significance. Vancouver Heritage Society, pp 1-10. Retrieved from: http://www.mole-hill.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Mole-Hill-Statement-of-Significance.pdf

- Grdadolnik, Helena. (2005) “Garden City,” Canadian Architect. Retrieved from: http://www.canadianarchitect.com/news/garden-city/1000199577/?&er=NA

- Ground-Oreiented, Medium Density Housing (GOMDH). (2003). “Best Practices in Housing,” Mole Hill Community Revitalization City of Vancouver, pp. 1-4. Retrieved from: http://www.metrovancouver.org/planning/development/housingdiversity/GOMDH2003/VancouverMoleHill.pdf

- Heritage Canada Foundation (2004). Mole Hill Community Housing Society of Vancouver, BC Receives Heritage Canada Achievement Award. Canada NewsWire, 1, p. 1. Retrieved from: http://search.proquest.com.proxy.library.carleton.ca/docview/455656424?pq-origsite=summon

- Mah, Cheryl. (2004) Mole Hill: New Honours for Vancouver’s Serenely Livable Heritage Neighbourhood. Journal of Commerce. 93.59. Retrieved from: http://search.proquest.com.proxy.library.carleton.ca/docview/215181494?pq-origsite=summon

- Mole Hill Community Housing Society. (2013). Providing and Advocating for Secure, Affordable Housing. Retrieved from: www.mole-hill.ca

- Mole Hill Community Housing Society, (2013). Mole Hill Newsletter May 2014, pp. 1-4. Retrieved from: http://www.mole-hill.ca/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/Newsletter-2.May-2014.pdf

- Open Green Building Society. (2013). “Design Centre for Sustainability,” Green Building Brain. Retrieved from: http://greenbuildingbrain.org/neighbourhoods/mole_hill

- Terra Housing. (2013) “Mole Hill Case Study,” Mole Hill Community Housing Society, pp. 1-2. Retrieved from: http://www.mole-hill.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Mole-Hill-Case-Study.pdf

- Vancouver Heritage Register (2014). “Land Use and Development Policies and Guidelines,”City of Vancouver, pp. 1-33. Retrieved from: http://former.vancouver.ca/commsvcs/guidelines/V001.pdf