Case study prepared by Dorian Pai of Carleton University.

401 RICHMOND, TORONTO: A HUB AND MODEL OF SUSTAINABILITY

Keywords: Toronto, Cultural Centre, Industrial heritage, Adaptive Reuse, Sustainability Challenges

The exterior of 401 Richmond facing the front entrance with its original, brick facade. Lima, E. (2017). 401 Richmond. [Photograph] Retrieved from http://www.metronews.ca/

401 Richmond serves not only as offices or workspaces, but is also the home to several art galleries, design stores, a daycare, and an accessible green roof. These functions, the building’s unique circumstances, as well as its developments, make 401 Richmond a valuable source of knowledge to learn from, especially as a model of:

- Successful rehabilitation: showcasing different approaches to adaptive reuse with alternative functions and ideas that can be adapted within an old building.

- Modern approaches to sustainability: utilizing new technologies and ideas to help promote both the social and environmental sustainability of a site.

- Challenges such rehabilitation projects may encounter: with threats to the economic sustainability of the building today as a cultural and heritage site in the context of Toronto’s accelerated development and property values.

In red is 401 Richmond Street West. Outlined is the King-Spadina Heritage Conservation Area that it is a part of. City of Toronto (2017), Proposed Plan Area.

PRESENTATION: This presentation, given to the class of CDNS 4403 on November 28, 2017, highlights some of the key themes and ideas that will be further discussed here about 401 Richmond. View it to get a quick grasp about 401 Richmond, its history, and its rehabilitation; more details of which can be found within this webpage.

The Dark Horse Espresso Bar in 401 Richmond featuring the original walls, flooring and supports that were preserved and have now become part of the space’s aesthetics. Dorian Pai (2017). 401 Richmond Interior.

DESCRIPTION: In 1994, the former factory was purchased by Margie Zeidler (Cohnstaedt, Shields, & MacDonald, 2003, p. 8.), daughter of the Toronto-based architect, Eberhard Zeidler of Toronto Eaton Centre and Ontario Place fame. Margie Zeidler also had big plans for 401 Richmond as a key, cultural site within Toronto and over the course of the next eighteen month, with her ideas in mind, led its rehabilitation. This development was prompted by the lack of affordable workspaces for the creative sector within the city. As a member of that community, Zeidler was aware of the issues and realized that 401 Richmond was an opportunity to tackle it (Hannon, 2007, p. 61.) perhaps even helping inspire more cultural spaces like it.

In addition, Zeidler pushed aspects of sustainability and cultural heritage with this adaptive reuse project. 401 Richmond was to not only serve as an affordable, creative work space but also a sustainable site that valued the heritage it was built within. There was respect for the environmental and social impacts of the building, viewed with various modern perspectives and ideas in mind to create a site of longevity and livability. There was also an understanding of what 401 Richmond represented, why it was valued, and how to preserve that value through its developments. All of these elements of 401 Richmond served as goals during its rehabilitation and are still very much important and relevant today playing a big part in its development as a commercial and cultural centre and heavily influencing the decisions made for the building moving forward.

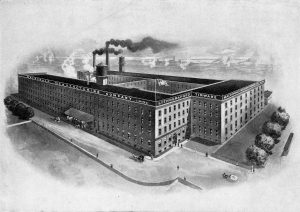

The original Macdonald Manufacturing Company from the early twentieth century during the height of the factory’s, and Toronto’s, industrial era. Artist Unknown. (Date Unknown). Works of Macdonald Mlg. Co., Limited. Retrieved from The history of the Macdonald Manufacturing Company Ltd. Toronto, Ontario.

TIMELINE

- 1899 – The Macdonald Manufacturing Company constructs a small, tin lithography factory (Lloyd, 1993, p. 1). Built during a wave of industrial development in Toronto along with several other manufacturers in the area, the factory quickly grew and expanded (City of Toronto, 2017, p. 6.).

- 1967 – There is a shift away from industry and manufacturing in Toronto, resulting in many factories moving elsewhere or closing, as the Macdonald Manufacturing Company did in 1967 (Cohnstaedt, Shields, & MacDonald, 2003, p. 8.). It passes through several hands for a variety of general use, though is largely left empty.

- 1994 – Margie Zeidler purchases the property and leads a rehabilitation project over the next 18 months, transforming the factory into a commercial and cultural centre (Cohnstaedt, Shields, & MacDonald, 2003, p. 8).

- 2007 – The site is designated as a municipal heritage site and added to the City of Toronto Inventory of Heritage Properties as “an outstanding example of the successful adaptive reuse of historic buildings.” (City of Toronto, 2006, p. 1.)

- 2016 – The site is designated as part of the King-Spadina Area as a Heritage Conservation Area. “As a whole, [the buildings] reflect the District’s evolution from an institutional and residential neighbourhood to a warehouse and manufacturing area over the course of the District’s period of significance.” (City of Toronto, 2017, p. 6.)

- 2017 – 401 Richmond faces issues of property taxes and its culture and function is threatened. As of the posting of this page, it is still working with both the municipal and provincial government in finding a solution.

STAKEHOLDERS

Owners

- Margie Zeidler – The president of 401 Richmond who initially purchased the property and started the rehabilitation project. She is trained as an architect and is heavily involved in several community projects both within and outside of Toronto (Hannon, 2007, 61).

- Urbanspace Property Group – Founded by Margie Zeidler, this organization owns and manages properties in Toronto, including 401 Richmond. They are in charge of the preservation of the building, its operation, its tenants, as well as carrying out Marge Zeidler’s vision.

Users

- The Tenants – Currently, there are 127 tenants utilizing 401 Richmond for a wide range of uses. Among them are 11 galleries, 7 publishers, 6 performance organizations, 3 architecture firms, 2 cafes, and a day care (401 Richmond, 2017. Tenants. http://www.401richmond.com/tenants/). They are an essential part to the building, contributing to its daily activities and livelihood.

Organizations

- City of Toronto – 401 Richmond plays an important part in the cultural community within Toronto as a centre of creative work and events. Additionally, the municipality has been working closely with 401 Richmond since its rehabilitation, especially during its heritage designation.

- Province of Ontario – Recently, 401 Richmond has been closely involved with the provincial government, discussing solutions and compromises to issues of property tax that may determine the building’s future.

HERITAGE: 401 Richmond has a long history in Toronto, stretching back to 1899 when it was constructed by the Macdonald Manufacturing Company. It served as a small factory for tin lithography but underwent several developments and expansions with the growth of the company (Lloyd, 1993, p. 59.). There are several industrial buildings in the area like it from the same era, all built in the period of 1880 to 1940 during a massive wave of industrial growth in Toronto. Many of these factories saw similar success up until the Second World War when the city began shifting away from manufacturing and heavy industries to tertiary services and products .

In 2007, the building was designated by the City of Toronto as a Municipal Heritage Site as “an outstanding example of the successful adaptive reuse of historical buildings” (City of Toronto, 2006, p. 1.). More recently, in 2016, the building was designated as part of the larger King-Spadina Heritage Conservation District by the city. In the designation reports, it is described that “as a whole, [the buildings] reflect the District’s evolution from an institutional and residential neighbourhood to a warehouse and manufacturing area over the course of the District’s period of significance” (City of Toronto, 2017, p. 6.).

This heritage remains an important part of the building’s character today, as well as the character of the area around it, helping define what it is and how it came to be. All of this was valued during 401 Richmond’s rehabilitation; its heritage was taken into account and also largely preserved. This was apparent by the very fact that the original building was not demolished or built over, but simply repurposed and renovated for its new functions. The brick exterior of the factory form was left undisturbed along with the original windows, which hold heritage value of its own in Toronto (401 Richmond, 2017. Architecture). Made of wood and steel, these were very large windows that lined each of the many hallways across the 3 floors that were originally made for factories like 401 Richmond to bring much needed light into the building. Decades ago, these windows would have been common to see around the various factories in the city, but today, few are left remaining, especially in such great condition. Although, work was done to the interior of 401 Richmond, its structure and layout was left largely the same, with the original, wooden supports and wooden flooring preserved. Parts of the building were even restored to their earlier industrial state, as seen with the years of paint stripped from the walls and windows (Cohnstaedt, Shields, & MacDonald, 2003, p. 8.).

Interior passage (Dorian Pai)

The building’s successful rehabilitation was recognized by several groups. This includes Heritage Toronto, who awarded the building the Award of Merit in 1999 for its “outstanding adaptive reuse of a historic building” (Cohnstaedt, Shields, & MacDonald, (2003), p. 8.).

Recognition of 401 Richmond’s cultural heritage values help emphasize its importance to the city and its people, and of preserving these values in older buildings like it. Especially amidst Toronto’s rapid growth today, older buildings such as this, as well as the history behind them, are disappearing and being forgotten. They are quickly being overshadowed and built over by new offices and condominiums that are also altering the character and identity of the city as a whole.

SUSTAINABILITY: Sustainability was another major goal in the rehabilitation project of 401 Richmond and still is an important part of the building’s philosophy today. A more modern approach was taken in regards to it, utilizing new technologies and ideas to better promote both social and environmental sustainability. This process makes the building a particularly interesting project to view as a model, to understand the different approaches that can be taken and its effectiveness.

Jane Jacobs and her ideas were so influential to the rehabilitation of 401 Richmond that a large painting and exhibit about her is displayed within the building. Dorian Pai (2017). 401 Richmond – Jane Jacobs. [Photograph]

401 Richmond’s rehabilitation can also be viewed alongside the modern ideas of Richard Florida, who helped popularize the concept of the “creative class” and the “creative city” as a new way of understanding the modern growth of cities today (Cohnstaedt, Shields, & MacDonald, 2003, p. 21.). With this concept, Florida draws upon the importance of “creative” professionals, including teachers, scientists, and artists, who produce goods and ideas that can fuel a city’s development. Many cities today have began acknowledging the potential of the “creative class” in urban development and growth, shifting their activities and focuses to better take advantage and attract this growing group. An important aspect of this is ensuring there are enough resources for the “creative class” to live, work, and thrive within, including appropriate facilities and services. 401 Richmond can be seen as such an asset providing affordable workspaces for artists and similar professionals as well as provide a central space for them to socialize and interact. The building has certainly helped drawn and retain this group and in turn, helped Toronto further develop as a “creative city”.

The award winning rooftop garden and green roof of 401 Richmond offering a nature filled retreat the busy city of Toronto around it.

Gareth Bate (Date Unknown) The stunning roof garden of 401 Richmond. [Photograph] Retrieved from http://www.garethbate.com/

Economic Sustainability: Despite 401 Richmond’s approaches and successes in social and environmental sustainability, it has recently been facing challenges of economic sustainability that threaten the building’s function and survival. Toronto continues to grow as a city, and nowhere is that more apparent than within the downtown core with new people and businesses moving in, and new highrises for offices and condos being built for them. There are few signs of this growth slowing down and it has led to drastic increases in property values and taxes. This has become an issue for many existing building like 401 Richmond, which have been struggling to keep up with this growth and its costs. Since 2012, property taxes have nearly doubled for 401 Richmond from $446,689 to $846,211 in 2017 (Whyte, 2017, p. 2.) This number is expected rise to $1,286,800 by 2020 (Whyte, 2017, p. 3.).

It was only recently, in September of 2017, that discussions with both the municipal and provincial government have made headway, as the province of Ontario announced a new tax class for buildings like 401 Richmond of cultural and heritage value within the community (Whyte, 2017, p. 1.). Although the exact numbers and details are still being discussed, this is certainly a huge step forward for not just 401 Richmond, but other buildings like it as well. There are several heritage sites and cultural centres within Ontario, many of which are smaller than 401 Richmond and some that have even already succumbed and closed. It is certainly not a unique situation and not one limited to just the province as well. As cities grow, this issue will almost inevitably reappear if it is not quickly recognized and learned from today.

REFERENCES

Books/Book chapters/Journal articles

- Brand, S. (1995). How Buildings Learn: What happens After They’re Built. New York: Penguin Books.

- Carroon, J. (2010) Sustainable preservation: greening existing buildings. New Jersey: Wiley.

- Elefante, C. (2007). The Greenest Building is… One That is Already Built. Forum Journal, 21(4), 67-72. Retrieved from https://muse.jhu.edu/.

- Jacobs, J. (1961). The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House.

- Maddex, D (Eds.). (1981). New Energy from Old Buildings. Washington: National Trust for Historic Preservation.

- Mieg, H. A., & Oeverman, H. (Eds.). (2014). Industrial Heritage Transformed, Clash of Discourses. New York: Routledge.

Policies and reports

- City of Toronto. (2017). King-Spadina Heritage Conservation District Plan. Retrieved from https://www.toronto.ca/.

- City of Toronto. (2017). Report for Action: Designation of the King-Spadina Heritage Conservation District under Part V of the Ontario Heritage Act. Retrieved from https://www.toronto.ca/.

- City of Toronto. (2017). Report for Action: Supplementary Report – Designation of the King-Spadina Heritage Conservation District under Part V of the Ontario Heritage Act. Retrieved from https://www.toronto.ca/.

- City of Toronto. (2006). Staff Report: 401 Richmond Street West – Inclusion on the City of Toronto Inventory of Heritage Properties and Intention to Designate under Part IV of the Ontario Heritage Act. Retrieved from https://www.toronto.ca/.

- Cohnstaedt, J., Shields, J., and MacDonald M. (2003). New Workplace Commons. Toronto: Ryerson & York University. Retrieved from http://www.401richmond.com/.

- Lloyd , L. L. (1993). The history of the Macdonald Manufacturing Company Ltd. Toronto, Ontario. Toronto: R. D. Lloyd.

Websites

- Hannon, G. (2007). Zeidler, Inc. Toronto Life, 39(7), 59-62. Retrieved from http://www.proquest.com/.

- Whyte, M. (2017). Good news for 401 Richmond – but what took so long?. The Toronto Star. Retrieved from https://www.thestar.com/.

- Whyte, M. (2017). Time running out for deal to save 401 Richmond. The Toronto Star. Retrieved from https://www.thestar.com/.

Banner image taken by Dorian Pai (2017)