Renewing Heritage for Art: Construction of the Judith and Norman Alix Art Gallery in Sarnia, Ontario

Case study prepared by Jack Mallon, Carleton University

Keywords: urban renewal, historic streetscape, socio-cultural sustainability, urban development, facadism

LESSONS LEARNED

The Judith and Norman Alix Art Gallery (JNAAG), operated by the County of Lambton, was constructed to fulfill the community’s need for a cultural institution that would contribute to the urban renewal of the downtown core whilst conserving the architectural heritage of the downtown streetscape. The gallery, a postmodern construction cloaked in the façade of the Victorian 1893 Thom Block, points to a problem encountered by many historical city centres, where heritage buildings are no longer able to meet the needs of the community without alterations, often extensive, that enable them to adapt to modern usage and societal trends. The gallery demonstrates how facadism can preserve historic streetscapes and architectural heritage while meeting the needs of a modern community.

Located in the heart of downtown Sarnia, the gallery is intrinsically linked to the cultural and economic revitalization of the downtown core and is mentioned in municipal and county plans as a component in the cultural sustainability of the region. However, evident in these plans is the difficulty encountered by governing bodies in articulating the precise contribution of the cultural dimension to community sustainability. The Lambton County Integrated Community Sustainability Plan notes that:

While the economic, environmental and social pillars have been well defined and documented in community sustainability planning, inclusion of the cultural pillar is a relatively new phenomenon in sustainable development. Lambton County has included the cultural pillar because of the important role that culture plays in defining our attitudes, values, and behaviours (2014, p. 18).

Though the plan identifies that “a community’s vitality and quality of life are closely related to the vitality and quality of its cultural engagement, expression, dialogue, and celebration” (2014, p. 18) specific language linking culture to sustainability is lacking. The arts are described as “a tool to foster social inclusion, cultural diversity, rural revitalization, public housing, health, ecological preservation, and sustainable development” (2014, p. 18) but the plan falls short of specifying how culture contributes to these aspects of sustainability. This is reflected in ICSP’s across Canada, where the inclusion of culture within conceptual and planning frameworks for community sustainability has tended to be vague and fractured (Duxbury & Jeanotte, 2012, p.1).

PRESENTATION

See presentation below which briefly summarizes the case study

Presentation: Renewing Heritage for Art

DESCRIPTION

The Judith & Norman Alix Art Gallery is a free public art gallery operated by the County of Lambton and located in downtown Sarnia, Ontario. With over 1,100 works of Canadian art in the permanent collection, the support of over 400 members, and a keen volunteer team, the gallery serves an immediate community of 128,000 people across Lambton County. JNAAG offers a “safe space that provides creative opportunities for people to connect, share stories, and discover new insights through art” (JNAAG, 2017). As the sole public art gallery in Lambton County, it engages with every artistic practice and media, from painting to performance art, and offers contemporary exhibitions that celebrate Canadian and international artists. The gallery provides the community of Lambton County with exciting access to exhibitions, programming and professional development opportunities (Artsbuild, 2013, p. 1).

Formerly known as “Gallery Lambton” and located in the Bayside Mall in downtown Sarnia, the County of Lambton Cultural Services Division recognized the need in 2009 to relocate the gallery to a new site that could meet the needs of the community and the collection. The County determined the new site would need to be within the downtown core, and the new space had to meet the physical requirements of a Category “A” gallery, yet reflect the gallery’s artistic vision (SNC Lavalin, 2009, p. 1). SNC Lavalin was hired in 2009 to conduct site assessments for three proposed locations. It ranked the Thom Block, locally known as the Saks building, as the best choice because it would contribute to the City of Sarnia’s economic revitalization along the waterfront, rescue an architecturally and historically significant building, assist in economic development, and become the focal point of a new “vibrant arts and cultural district” (SNC Lavalin, 2009, p. 23).

The Thom Block, erected in 1893 to house the photography studio of Major J.S. Thom, was one of the few Victorian facades to survive the 1953 Tornado and urban renewal of the 1960’s. The building had functioned as a bank, a dentist’s office, a stationary shop, and a women’s clothing store. Vacant for 25 years, by 2009 it was in a state of severe disrepair, with significant structural deterioration. The site assessment indicated that in order to meet the requirements of a category “A” gallery the interior would have to be demolished and replaced with a new structure.

The design conceived by Architect Alar Kongats would synthesize postmodern and Victorian architectural styles to create a gallery that would both enhance and respect the historic downtown streetscape. The two street-facing façades of the Thom block would form the exoskeleton of the new building, and a third story, set back and clad in contrasting metal sheeting, would be added to meet the 17,400 square foot requirement of the gallery (SNC Lavalin, 2009, p. 2). Temporarily shored by steel beams, the interior of the Thom Block was demolished in 2010 and the façade was stripped of the exterior lead paint to reveal the original red brick and granite lintels. The brick was repointed, and the foundation stabilized by Empire Restoration (JNAAG, 2011). A heritage staircase was salvaged from the interior, restored, and reinstalled in the foyer of the gallery. The dark wood staircase now dominates the first floor of the gallery and contrasts with the modern white walls and glass windows; a stark reminder of the building’s past.

TIMELINE

The timeline is divided into two sections to reflect the life of the building: First, as it was originally constructed by J.S. Thom and, secondly, its transformation into the Judith and Norman Alix Art Gallery.

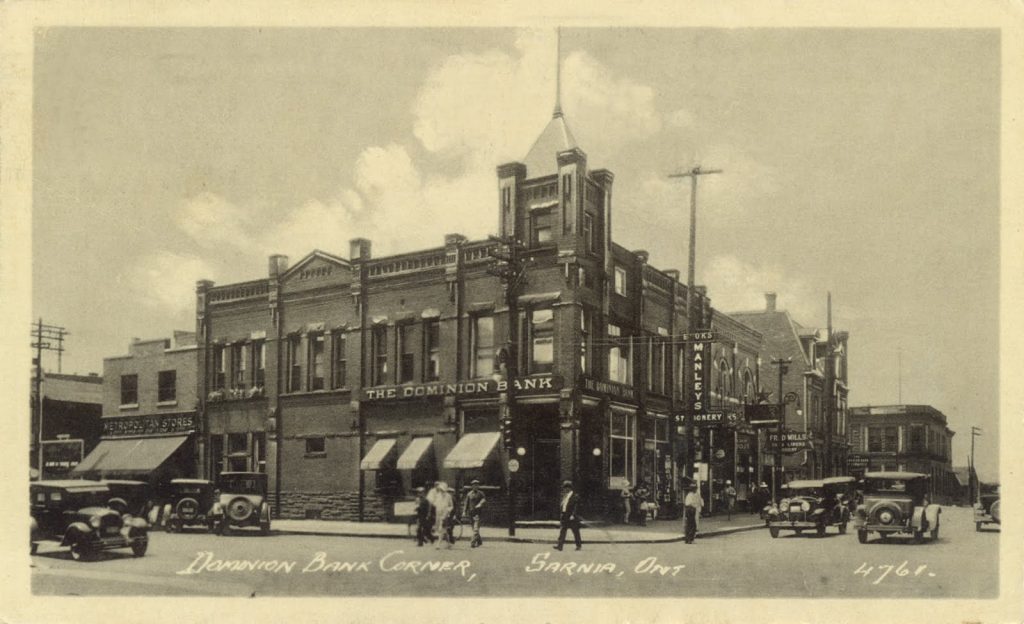

The Thom Block (Ontario Photos and Photographers, 2010; Rochon, 2010)

| 1890 | McLellan Hotel is destroyed by fire | |

| 1893 | Major J.S. Thom erects building for photography firm | |

| 1893 – 1920 | J.S. Thom photography studio (2nd floor) | |

| 1893 – c. 1960 | Dominion Bank and Manley’s Stationary (1st floor) | |

| c. 1960 | Saks Women’s Clothiers (1st and 2nd floors) | |

| 1977 | Saks purchases and installs c. 1870 staircase | |

| c. 1985 | Saks closes | |

| 1986 – 2010 | Thom Block is vacant |

Construction of JNAAG (JNAAG Project Blog, 2010-2012)

| 2009 | Thom Block chosen as site of new gallery | |

| Aug. 2010 | Demolition of interior begins | |

| Sept. 2010 | Support beams installed to shore façade | |

| Feb. 2011 | work begins on third level | |

| May 2011 | lead paint removed from façade | |

| June 2011 | Roof installed | |

| July – Aug. 2011 | Brick repointed | |

| Oct. 2011 – March 2012 | Interior construction | |

| July 2012 | Permanent collection moved to JNAAG | |

| October 2012 | Gallery opens to public |

STAKEHOLDERS

From proposals for a new location to the design and construction of the new gallery, the County of Lambton made every attempt to include the community in the process to create JNAAG. JNAAG was constructed in conjunction with the city of Sarnia’s downtown revitalization project, which complemented the building of the gallery with new infrastructure and the downtown business façade improvement program (Artsbuild, 2013, p.4). Proposals for a new location were welcomed from the community and advice was sought from relevant community groups.

Funding for the project was provided from federal, provincial, county, municipal, and private donors. Lambton County committed $2.6 million for the project and Canadian Heritage’s Canada Cultural Spaces Fund provided a $3 million grant (County of Lambton, 2009). The Judith and Norman Alix Foundation, a philanthropic organization dedicated to improving quality of life in Lambton County, donated $1.5 million to the project (Judith and Norman Alix Foundation, 2019). This generosity was recognized by changing the gallery’s name from “Gallery Lambton” to the “Judith and Norman Alix Art Gallery. It should be noted that funding for the gallery was provided by donors too numerous to list in this case study. The list above reflects donations of $50,000 or more.

| Government | City of Sarnia County of Lambton Province of Ontario Department of Canadian Heritage Sarnia Heritage Committee | |

| Donors | Judith and Norman Alix Foundation CIBC County of Lambton Councillors and Employees Sarnia Construction Association Enbridge Pipelines Inc. Steeves and Rozema Enterprises Ltd. Fairbank family Thomas and Maxine Kenny Numerous private donation of $49,000 or less (JNAAG, 2017) | |

| Community | Downtown businesses and residents Lambton County residents Gallery members/staff/volunteers Sarnia Historical Society | |

| Construction | Empire Restoration PCR Construction Maple Industries | |

| Consultants | Alar Kongats, Architect MIG Engineering SNC Lavalin Pro Fac Inc. Others include: real estate professionals, LEED certified architect, building professionals, art gallery professional, structural engineer, county representatives. |

HERITAGE

Natural Heritage: The urban location of JNAAG dictates that there is little to no natural heritage on the site itself. However, the development of Sarnia as a port town in the mid-nineteenth century is reflected in the downtown core’s orientation towards the waterfront. The city’s economic shift from shipping to chemical processing, combined with the 1953 tornado that destroyed waterfront commercial structures, resulted in the shipping-oriented waterfront being converted into a park. This park, approximately 100 meters from JNAAG, is designated in the Lambton County Official Plan as a primary corridor: A regionally important concentrations of natural heritage features and/or large, naturally vegetated, natural areas (County of Lambton, 2014).

The St. Clair River, a south flowing river between the United States and Canada that connects Lake Huron to Lake St Clair, defines the eastern boundary of the downtown core. Formerly a bustling port, the waterfront is now populated primarily with recreational boaters and anglers, though the St. Clair River remains a significant international shipping lane. The river was designated an International Area of Concern in 1985 “because available data and field studies indicated that water quality and environmental health were severely degraded. A history of industrialization, urbanization and agricultural land use activities on the St. Clair River and in its tributary watersheds” led to 9/14 of the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement beneficial use indicators being deemed as impaired (Government of Canada, 2017).

Cultural Heritage: Downtown Sarnia maintains a unique sense of place and human scale derived from its history, architecture, and streetscapes. Once packed by Victorian commercial buildings, the 1953 tornado caused irreparable structural damage to many of the downtown’s nineteenth-century brick structures. From this devastation arose urban renewal projects of the 1950’s and 1960’s that resulted in the creation of a modern city hall, library, and post office (Gamble, 2016). The Thom Block is one of the few Victorian facades to survive into the twenty-first century.

Constructed in the Italianate style (Blumenson, 1990, p.27) and erected in 1893, the red brick Thom Block dominated the southwest corner of Lochiel and Christina streets in the heart of downtown Sarnia. According to the Sarnia Heritage Committee’s (SHC) Heritage Inventory, “the architecture of this building… is rare and unique within the city… particularly important to the overall appearance of the building is the tower” (SHC, 2010, p. 368). The building originally housed the photography studio of Major J.S. Thom on the second floor with the Dominion Bank and Manley’s stationary on the first floor (Rochon, 2010). From the 1960’s until the mid 1980’s it housed Saks women’s clothiers. In 1977 the owner of Saks bought an ornate walnut staircase from one of Sarnia’s earliest banks located at 149 Front St. (Rochon, 2010). Saks closed in the mid 1980’s and the Thom block was vacant for 25 years.

Though part of Sarnia’s Heritage Inventory, the block was set for demolition several times during its vacancy (Rochon, 2010). The SHC, a pro heritage municipal committee, commended “the decisions made to preserve the façade of the building and the internal staircase” and identified that the façade was important to the “historic architectural character of the Sarnia’s Downtown” (SHC, 2010, p. 127). In a 2010 letter, the committee maintained “that all efforts must be made to incorporate the original façade, especially the tower of the building, into the new development” (SHC, 2010, P. 127). However, the peak atop the turret at the corner of Locheil and Christina streets was a roadblock to achieving the 17,400 square foot required for the gallery. The design team collaborated with the Sarnia Historical Society and the SHC and concluded that a peak would be reflected through the situation of exterior “A” and “G” letters added to the gallery roof (Artsbuild, 2013, p.3).

In the site assessments the project is repeatedly described as “adaptive re-use” of a heritage structure (SNC Lavalin, 2009, p. 24). However, because the entirety of the block’s interior was demolished, save for the staircase, the JNAAG project is more aptly described as facadism. According to Kyiazi, “façadism lies in the grey zone between building conservation and development (2019, p. 185). Facadism is frequently criticized for disregarding authenticity, as it supposedly “disguises major destruction of the physical and social fabric and to cultural identity” (Rodwell, 2003, p. 62). However, JNAAG utilized a heritage structure that was likely to be demolished. The new structure both preserved and enhanced a significant component of the downtown streetscape and strengthened the cultural identity of the region by housing the county’s significant art collection in a building swathed in an architecturally significant façade. JNAAG houses a permanent collection of primarily Canadian historical and contemporary works of regional and national significance. The permanent collection is founded upon works collected during the interwar period by the Sarnia Women’s Conservation Art Association. Donated to the Sarnia Library in 1956, these works formed the foundation of the permanent collection (JNAAG, 2017). Initially exhibited on the second floor of the Sarnia Library, the collection was moved to Gallery Lambton in the Bayside Mall, a space that did not meet the spatial and environmental requirements of the collection. (SNC Lavalin, 2009, p. 1). The JNAAG, constructed using the façade of the Thom Block, between 2010-2012, now houses the permanent collection and, as a Category A gallery, can exhibit moveable cultural heritage from other Canadian institutions.

SUSTAINABILITY

Environmental Sustainability: Though recommended in the 2009 SNC Lavalin site assessment, the building is not LEED certified. This is likely due to the excessive energy consumption required to maintain the high standard of environmental control required by a Category A gallery. The LEED assessment noted that the Thom Block proposal “demonstrated no commitment, construction, or cost allocation for LEED in the proposal,” and there was “no provision in the design for recyclables,” and no “waste management plan” (SNC Lavalin, 2009, Appendix B).

JNAAG’s location in the centre of Sarnia’s downtown core provides excellent access for pedestrians and cyclists and thus encourages active transport. During the construction of JNAAG the lead paint was removed from the exterior of the building utilizing an environmentally safe method that keeps the lead paint in a wet state, so no airborne lead dust is generated (JNAAG, 2011).

The gallery is located in an area that is identified by the City of Sarnia as being “partially affected” by flooding and sewer overflow (Irwin, 2019). The first floor is level with the street and would thus be susceptible to flooding that rose above the sidewalk. However, the collection and the exhibition galleries are located on the upper floors, safeguarding them from the impact of flooding on the first floor or basement levels.

Social Sustainability: According to Polèse et al, “the sustainability of cities and the quality of life they provide for all their citizens are shaped not only by the quality and distribution of “hard” public services, but by policies that address social activities” (Polèse et all, 2000, p.22). Art galleries improve social and cultural development by creating better urban life (Polèse et all, 2000, p.171). With no cost of admission and full physical accessibility for all gallery space, JNAAG’s services are available to all demographics of the Lambton County community. According to the Sarnia Official Plan, culture is a meaningful and tangible contributor to quality of life, and cultural activities foster community participation and social cohesion (City of Sarnia, 2014, p. 97).

Cultural Sustainability: According to Hawkes, the arts are the paramount symbolic language through which shifting social meanings are articulated. Active community participation in the arts contributes toward a more inclusive and engaged democracy (Hawkes, 2001, p. 30). The relocation of Gallery Lambton to the Thom Block site was intended to “reflect the community value of the artistic content” (SNC Lavalin, 2009, p. 51) of the gallery. Public engagement through the arts empowers people to be reflexive and emotional in a way that traditional forms of engagement cannot access (O’Shea, 2011, p. 34).

The Sarnia Official Plan recognizes JNAAG, in conjunction with the Sarnia Library as “major public cultural facilities in the downtown that together with entertainment facilities, speciality industries and artisans form a regionally significant cultural cluster” (2014, p. 65). The County of Lambton Cultural Plan (CLCP) states that “creativity, culture and quality of place are fundamental to building a sustainable, prosperous and diversified economy and providing a superior quality of life for [Lambton County] residents” (2013, p.1). The provision of “a wide range of art and art practices” (JNAAG, 2019) to the Lambton County community fosters creativity and dialogue. According to the CLCP, “a creative community is a healthy community that supports the protection of our environmental and natural heritage resources” (2013, p.1).

Economic Sustainability: In the SNC Lavalin site assessment, the Thom Block was emphasized as possessing the best “potential to act as a catalyst to the arts and cultural community… It has the potential to attract restaurants, cafes, music stores and other private galleries” (SNC Lavalin, 2009, p.24). The assessment argued that the Thom Block site “will draw tourists from the waterfront to the gallery, Sarnia’s main street, and downtown core, spurring spin-off spending… anticipated to act in a major way as a catalyst for related and ancillary economic development in the vicinity (SNC Lavalin, 2009, p.24). Both the Sarnia and Lambton Official Plans recognize that “a flourishing cultural life is a magnet that attracts tourists, residents and businesses to the city, and encourages existing residents and businesses to stay (City of Sarnia, 2014, p. 97). This is a common tactic for downtown revitalizations, as support for cultural intuitions often translates into commercial advantage (Polese et al, 2000, p. 22). The dual role of JNAAG as both an art gallery and significant contributor to the downtown streetscape gives it instrumental value for creating a sense of identity for people living close to that site and for raising economic well-being through tourism (Soni, 2016, p. 167). The gallery’s capacity to bring visitors to the downtown is demonstrated by the over 18,000 visitors that attended the “Masterworks” exhibition in late 2015/early 2016 (JNAAG, 2016).

MEASUREMENT

Integrated Community Sustainability Plans: JNAAG primarily contributes towards the social and cultural pillars of sustainability as outlined in the Lambton County Integrated Community Sustainability Plan. The gallery and other downtown cultural institutions were identified by the city of Sarnia as forming a “cultural cluster” (City of Sarnia, 2014, p. 65) which is essential to creating a vibrant downtown that functions as a social, cultural, and economic hub in the community (Lambton County, 2013, p. 1). However, as Duxburn and Jeanotte note in their study of Canadian Integrated Community Sustainability Plans (ICSP), the inclusion of culture within conceptual and planning frameworks for long-term community well-being and sustainability has tended to be vague and fractured (Duxbury & Jeanotte, 2012, p. 1). The Lambton County Integrated Community Sustainability Plan is not alone in lacking both a definition of culture and specifications on how culture can contribute to sustainability.

The inclusion of culture in Canadian ICSP’s is rationalized by either its economic or social contributions. In the plans, culture is either defined as an asset that enhances touristic economic development, aesthetic and architectural attractiveness, and downtown revitalization or as contributing to quality of life, community engagement, social cohesion, and collective identity (Duxbury & Jeanotte, 2012, p.9). The Lambton County ICSP combines both the economic and social definitions to identify culture as “fundamental to building a sustainable, prosperous and diversified economy and providing a superior quality of life for [Lambton County] residents” (Lambton County, 2013, p. 7).

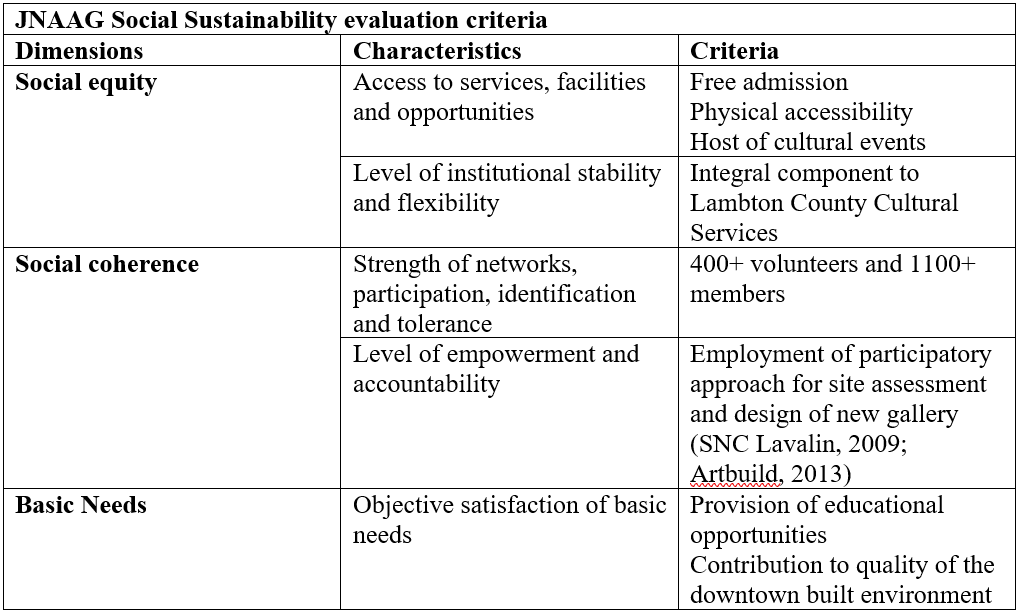

Landorf’s evaluation of social sustainability: JNAAG’S contribution to community social sustainability, broadly defined for this case study as the provision of “equal access to services and opportunities” (Landorf, 2011, p. 465) is articulated by the gallery’s guiding principle: “Visual art and visual culture, with its capacity to embrace and reflect the multifaceted makeup of our society, is a powerful and vital medium that stimulates opportunities for creative exchange and discovery” (JNAAG, 2019). JNAAG strives to make “art and visual culture relevant to a wide demographic” in the Lambton County community and utilizes art and art practices “to provide opportunities for engagement that draws on the experience and stories of the region as a reference point (JNAAG, 2019).” JNAAG’s specific contributions to social sustainability can be measured using Landorff’s “Social sustainability evaluation criteria for historic urban environments” (Landorf, 2011, p. 472):

United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: JNAAG’s contribution to the quality of life in Sarnia and Lambton County makes it a localized contributor to United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goal 11: “Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable”.(United Nations, 2015). Specifically, JNAAG contributes to

- target 4, to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural heritage, and

- target 7 , to provide universal access to safe, inclusive and accessible, public spaces.

Environmental control standards for museums: Ensconced in a heritage façade, JNAAG safeguards movable cultural heritage and in a physically accessibility and free public space. Specific metrics to measure the environmental sustainability of the JNAAG are not publicly available. However, designated a “Category A” institution by the Canadian Conservation Institute, the JNAAG must meet strict environmental controls as prescribed by the American Society of Heating, Refrigeration, and Air Conditioning Engineers Inc. (ASHRAE) Handbook. These strict environmental controls require integrated design, construction, and operations to achieve stipulated condensation control, humidity control, UV control, thermal resistance, lighting control. Class A environmental control designation requires “short-term fluctuations of ±5% RH and ±2°C, with a seasonal temperature change of up 5°C and down 10°C, and a seasonal humidity change of up 10% RH and down 10% RH” (Grattan & Michalski, 2017). Although JNAAG’s modern construction suggests energy efficiency, conditioning the indoor climate of museums according to a strict climate class results in excessive energy consumption (Kramer et al, 2016, p. 286).

REFERENCES

Books/Book chapters/Journal Articles

- Blumenson, J.J. (1990). Ontario architecture: A guide to styles and building terms, 1784 to the present. Markham: Fitzhenry & Whiteside.

- Duxbury, N., & Jeannotte, M. S. (2010, August). Culture, sustainability and communities: Exploring the myths. In 6th International Conference on Cultural Policy Research, Jyväskylä, Finland (pp. 24-27).

- Duxbury, N., & Jeannotte, M. S. (2012). Including culture in sustainability: an assessment of Canada’s Integrated Community Sustainability Plans. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, 4(1), 1-19.

- Duxbury, N., Jeannotte, M. S., Andrew, C., & Mateus, J. M. (2012). Culture in Sustainable Communities: Integrating Culture in Community Sustainability Policy and Planning in Canada and Europe. In Presentation at the International Conference on Cultural Policy Research, Barcelona, Spain, July (pp. 9-12).

- Hawkes, J. (2001). The fourth pillar of sustainability. Culture’s Essential Role in Public Planning. Melbourne, Australia.

- Kramer, R. P., Schellen, H. L., & Van Schijndel, A. W. M. (2016). Impact of ASHRAE’s museum climate classes on energy consumption and indoor climate fluctuations: Full-scale measurements in museum Hermitage Amsterdam. Energy and Buildings, 130, 286-294.

- Kyriazi, E. (2019). Façadism, Building Renovation and the Boundaries of Authenticity. Aesthetic Investigations, 2(2), 184-195.

- Landorf, C. (2011) Evaluating social sustainability in historic urban environments, International Journal of Heritage Studies, 17:5, 463-477.

- O’Shea, M. (2011). Arts engagement with sustainable communities: Informing new governance styles for sustainable futures. Culture and Local Governance, 29-41.

- M., Stren, R. E., & Stren, R. (Eds.). (2000). The social sustainability of cities: Diversity and the management of change. University of Toronto Press.

- Soini, K., & Dessein, J. (2016). Culture-sustainability relation: Towards a conceptual framework. Sustainability, 8(2), 167.

Policies and Reports

- County of Lambton (2009). County of Lambton Announces Site for New Public Art Gallery. Retrieved from https://www.lambtononline.ca/home/government/newsreleases/Lists/News%20Releases/DispForm.aspx?ID=391

- County of Lambton (2009). Gallery Lambton expansion planning study. https://www.lambtononline.ca/home/government/countydivisions/administration_cao/Pblictions/Documents/TCI%20study%20-%20Gallery%20Lambton.pdf

- County of Lambton (2019). Official Plan. https://www.lambtononline.ca/home/residents/planninganddevelopment/Documents/Official%20Plan%20Documents%20-%202019/Lambton%20County%20Official%20Plan%20-%20Portions%20Under%20Appeal%20Noted.pdf

- County of Lambton (2013). Integrated community sustainability plan. https://www.lambtononline.ca/home/government/SustainableLambton/Documents/Lambton%20ICSP.pdf

- County of Lambton (2019). Official plan: natural heritage systems. https://www.lambtononline.ca/home/residents/planninganddevelopment/Documents/Official%20Plan%20Documents%20-%202019/LC_OP_NaturalHeritage_System_Map2_FINALVersion7_May_2019_NoSecondary_MMA.pdf

- Government of Canada (2017). ‘St. Clair River: Area of concern.’ In Great Lakes Areas of Concern. https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/great-lakes-protection/areas-concern/st-clair-river.html

- Sarnia Heritage Committee (2009). ‘Agenda Item C,’ in Sarnia City Council Agenda and Minutes Feb. 8, 2010. https://sarnia.civicweb.net/document/9853

- Sarnia Heritage Committee (2010). Heritage Inventory. https://www.sarnia.ca/doing-business/cultural-heritage/

- SNC Lavalin ProFac (2009). County of Lambton Gallery Lambton site assessment.https://www.lambtononline.ca/home/government/countydivisions/administration_cao/Publictions/Documents/SNC%20Lavalin%20Pro%20Fac%20Report%20%20Gallery%20Site%20Assessment.PDF

Websites

- Artsbuild Ontario (2013). Making spaces for art. Retrieved from https://www.artsbuildontario.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/Making-Spaces-for-Art-Alix-Art-Gallery-FINAL.pdf

- Federation of Canadian Municipalities (2014). City of Sarnia Integrated Community Sustainability Plan. Retrieved from https://fcm.ca/en/resources/gmf/case-study-city-sarnia-integrated-community-sustainability-plan

- Gamble, Adrien (2016). “How a 1950s tornado kickstarted urban renewal in the imperial city,” Skyrisecities. Retrieved from https://skyrisecities.com/news/2016/07/cityscape-how-1950s-tornado-kickstarted-urban-renewal-imperial-city

- Grattan, D. and Michalski, S. (2017). ‘Environmental guidelines for museums,’ Preventative Conservation, Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/conservation-institute/services/preventive-conservation/environmental-guidelines-museums.html

- Irwin, M. (2019: March 28). “Sarnia gets $10M to prevent flooding.” Blackburn News. Retrieved from https://blackburnnews.com/sarnia/sarnia-news/2019/03/28/sarnia-gets-10m-prevent-flooding1/

- Rochon, J. (2007). “Downtown Sarnia.” Flickr. Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/34370769@N07/albums/72157612531691205

- Judith and Norman Alix Art Gallery (2014). JNAAG project blog. Retrieved from http://gallerylambton-onsite.blogspot.com/2010/09/perfect-september-day-for-construction.html

- Judith and Norman Alix Art Gallery (2017). Mandate, vision, and guiding principles. Retrieved from https://jnaag.ca/about/

- Judith and Norman Alix Art Gallery (2017). Donors Gallery. Retrieved from https://jnaag.ca/join-give/donors-gallery/

- Judith and Norman Alix Art Gallery (2016). Over 18,000 visitors to the masterworks! Retrieved from https://jnaag.ca/over-18000-visitors-to-the-masterworks/

- Judith and Norman Alix Foundation (2019). Judith & Norman Alix Art Gallery. Retrieved from https://jnaf.ca/projects/judith-norman-alix-art-gallery/