Ji-ganawendamang Gidakiiminaan: Pimachiowin Aki and the Value of Living Cultural Landscapes

Case Study prepared by Samantha David, Carleton University

Keywords: Indigenious Knowledge, Indigenous Peoples, Self-Determination, Community-Driven Development, Stewardship

- Lessons Learned

- Description

- Timeline

- Rightsholders and Collaborators

- Heritage

- Sustainability

- Measurement

- Works Cited

LESSONS LEARNED

Heritage conservation needs to explore ways in which alternative interpretations of heritage can be meaningfully protected and engaged with. One step towards the expansion of this idea can be found through the experiences of the Pimachiowin Aki Corporation in their journey to attain the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Site listing. Pimachiowin Aki is not only significant for its distinctive mixed-heritage landscape, but it also serves as a major milestone in the international discourse of how outstanding universal values may be interpreted. Driven by First Nations interests and supported through co-governance mechanisms, this site is unique in that this process was Indigenous-led and defined, and was successful in an international fora with limited understandings of Indigenous notions of place.

Pimachiowin Aki is important as it offers an exceptional example of how heritage conservation can be inherently sustainable, and how the values of sustainability can, in themselves, be interpreted as cultural heritage. Anishinaabe practices of Ji-ganawendamang Gidakiiminaan, or Keeping the Land, offer exciting imaginaries of heritage conservation as an intergenerational, interdependent and experiential practice. It is through supporting Indigenous leadership in the protection of the land that we enable the protection of cultural heritage. By shifting cultural interpretations of heritage value, there is an opportunity to reconsider the relationship between sustainability and heritage conservation to not be conflictual, but complementary practices. This benefits not only the health of the lands we learn, live and play on, but it serves as a mechanism through which governments of all jurisdictions can advance tangible actions towards respecting Indigenous rights and treaties.

This case study will explore these themes, illustrating the journey to Pimachiowin Aki’s inscription and providing a theoretical exploration of living heritage and its inclusion in the current heritage ecosystem.

PRESENTATION

This slide presentation was presented at Carleton University in CDNS 5403 (Heritage Conservation and Sustainability in Canada) on November 24, 2022, a course associated with the School of Indigenous and Canadian Studies.

DESCRIPTION

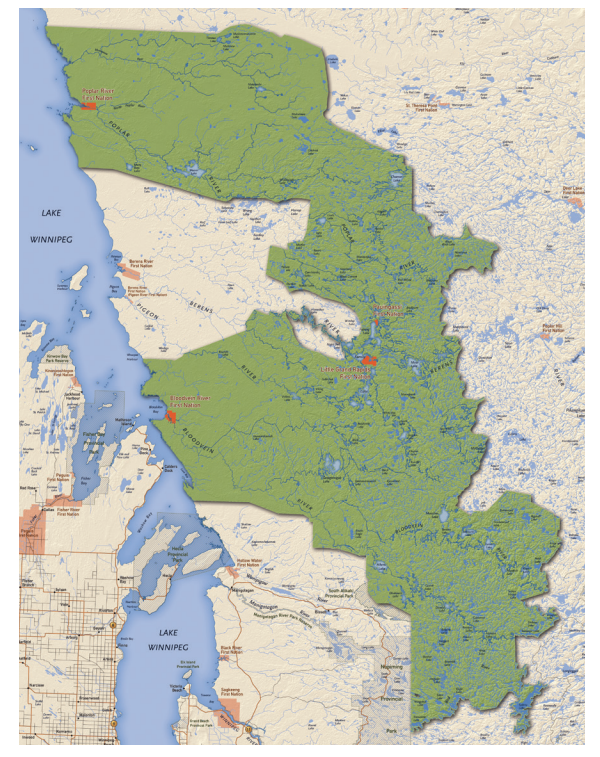

Pimachiowin Aki (pronounced pim-MA-cho-win ah-KAY), also known as The Land that Gives Life, is a mixed-heritage landscape and UNESCO World Heritage Site located between the provinces of Manitoba and Ontario along the eastern shores of Lake Winnipeg. It is the ancestral land of the Anishinaabeg located in Treaty 5 territory and comprises the traditional territory of four First Nations, three provincial parks and one conservation reserve (Pimachiowin Aki Corporation 2021, 3). At 29,040 square kilometres, it is the largest protected area in the boreal shield and is home to a significant amount of wetlands and biodiversity (Pimachiowin Aki Corporation 2022, Fast Facts).

The landscape is significant not only because of its impressive natural features, but its role in shaping Anishinaabe worldviews and history. The land is home to hundreds of distinctive place names, thousands of pictographs and ceremonial sites that have been used since time immemorial (UNESCO World Heritage Centre 2022). The UNESCO World Heritage Centre highlights this:

“Pimachiowin Aki thus expresses an outstanding testimony to the beliefs, values, knowledge, and practices of the Anishinaabeg that constitute Ji-ganawendamang Gidakiiminaan; the persistence of Anishinaabe customary governance ensures continuity of these cultural traditions across the generations.”

(2022)

As a mixed-heritage landscape, Pimachiowin Aki met the listing criterion in the following ways:

- Criterion (iii): Pimachiowin Aki is an exceptional testimony to the continuing Anishinaabe cultural tradition of Ji-ganawendamang Gidakiiminaan (Keeping the Land)

- Criterion (vi): Pimachiowin Aki is embedded in the living tradition and beliefs of the Anishinaabeg, and thus possesses both tangible and intangible heritage characteristics.

- Criterion (ix): Pimachiowin Aki is the most complete and the largest example of the North American boreal shield, with all its biodiversity and ecological processes. (2022)

The wording for this criterion proved to be a challenge to Pimachiowin Aki’s initial nomination, as many of the concepts of outstanding universal value translated poorly in anishinaabemowin and thus caused tensions in its assessment (Rabliauskas 2020, 11). In particular, the initial assessments by the World Heritage Committee utilized a deficit-lens on the lifestyles of First Nations living in Pimachiowin Aki, casting doubt on their leadership abilities despite the fact that the nomination was an assertion of their land and treaty rights by those very communities (2020, 12).

It is in recognition of these challenges that the commemoration of Pimachiowin Aki is so significant, as it marks two decades of ongoing collaborations and a milestone shift in the cultural mindset of international bodies such as the World Heritage Committee and its advisory bodies of the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). As a site with intimate interlinkages between nature and culture, Pimachiowin Aki is a shining example of living heritage and the capability of heritage conservation to expand beyond the socially-constructed binary values of natural and cultural heritage.

TIMELINE

| Time | Event |

| Time Immemorial-Present | Pimachiowin Aki is actively occupied by the Anishinaabeg, shaping culture, language and the natural landscape |

| 1875 | Treaty 5 is signed, outlining the ongoing rights of First Nations within the area of Pimachiowin Aki and the obligations of the Government of Canada to uphold them (Pimachiowin Aki Corporation 2022, Timeline). |

| 2002 | The Cooperative Relationship Accord was struck between four First Nations (Poplar River First Nation et al, 2002). Simultaneously, the Government of Manitoba and the Government of Ontario identified an interest in developing a more robust woodland caribou conservation area (Rabliauskas 2020, 10). These mutual interests begin a dialogue. |

| 2006 | Pimachiowin Aki Corporation is established. |

| 2009 | Bloodvein River First Nation joins Pimachiowin Aki Corporation, increasing First Nation membership to five nations (CPAWS Manitoba 2009). |

| 2012 | The first UNESCO World Heritage Site nomination bid was made on behalf of the Pimachiowin Aki Corporation. (Pimachiowin Aki Corporation 2022, Timeline). |

| 2013 | Initial application was deferred by UNESCO, as the evaluation metrics were insufficient to assess a mixed-heritage cultural site of this design. A working group with ICOMOS and IUCN, in collaboration with Pimachiowin Aki Corporation was established (UNESCO World Heritage Centre 2013). It is important to note that in the official deferral, there is a clear lack of understanding on how natural and cultural heritage may be interdependent on one another. The factual errors letter linked to the original assessment indicate a lack of understanding about Indigenous occupation, treaty rights and their placement as part of Canada’s larger judicial system, and lack of recognition for Indigenous land stewardship practices such as aquaculture. The assessors failed to spell the park names correctly throughout the entirety of the assessment as well, indicating a lack of basic care for the nomination (UNESCO 2013, 3-10). |

| 2016 | The second attempt at the UNESCO World Heritage Site listing begins. It is deferred a second time. Pikangikum First Nation chooses to leave the Pimachiowin Aki Corporation. |

| 2017 | The third nomination bid for the UNESCO World Heritage Site listing is submitted with amendments to reflect the change in partnerships. |

| 2018 | Pimachiowin Aki Corporation is successful in achieving the UNESCO World Heritage Site listing, making it the first and only mixed-heritage site in Canada. |

RIGHTSHOLDERS AND COLLABORATORS

Pimachiowin Aki Corporation:

- Bloodvein River First Nation

- Little Grand Rapids First Nation

- Pauingassi First Nation

- Poplar River First Nation

- Government of Manitoba

- Government of Ontario

The Pimachiowin Aki Corporation is a non-profit charity organization consisting of the key decision-makers for Pimachiowin Aki. Representatives from each community and partner department are included on the board of directors. Annual reports on site activities and ongoing alignment of interests through eight1 different land management plans are integrated into their key operations (Government of Canada 2016, 35).

Former Partners:

- Pikangikum First Nation

It is important as part of the assessment of the partnership to be mindful of, and recognize the contributions of Pikangikum First Nation in the pursuit for the UNESCO listing. As a founding member of the partnership, they contributed time and effort into the development of the original nomination.

Government Collaborators (Advisory):

- Parks Canada

Relative to other heritage sites, Parks Canada has a minimal role administratively in the support of Pimachiowin Aki. This is not to say that the partnership is inadequate, but that it requires a unique framing as Parks Canada does not hold the same scale of decision-making power over Pimachiowin Aki. Parks Canada provided technical support to the initiative, offering guidance in filling out the UNESCO nomination and representing the application on behalf of the Pimachiowin Aki Corporation as the main lead agency for the implementation of the World Heritage Convention in Canada (Government of Canada 2018).

HERITAGE

The question of heritage values represents the core challenge of Pimachiowin Aki’s journey towards its World Heritage Site commemoration. In particular, existing heritage conservation theories, practices and beliefs struggle with how heritage is classified.

Joe Watkins highlights this as a struggle between tangible heritage – that which can be touched and seen, intangible heritage – that which is composed of social constructs and knowledge, and immovable heritage – landscapes that have significance to a particular group (Watkins 2019). An additional construct, that of natural and cultural heritage, creates a secondary regulatory binary that lies embedded in UNESCO through two separate advisory bodies, ICOMOS and IUCN (Singh 2011, 87). It is worth noting that the fundamental structures of international heritage conservation are constructed upon Eurocentric conceptions of preservation (Singh 2011, 84), and thus serve to reinforce these structures by existing.

For Indigenous communities, these values are not conflicting but interdependent (Watkins, 2019). It is not the label of heritage that is ascribed to a place that is important, more as the actions that are taken to ensure its longevity for generations to come. Living heritage, or the notion of natural and cultural heritage in its totality, needs people to care for it as much as people require engagement with heritage for their own well-being. Elder Albert Bittern describes it as such:

“We all fit side by side on this circle of life, and we all are important, depending on each other for life. No one is more important than the other. That is why we have a strong relationship with all life.”

(As cited in Jones 2018, original quote said November 2013)

How can living heritage be understood in this context, and how might it be evaluated? For the Anishinaabeg, the conceptualization of this relationship is described through Ji-ganawendamang Gidakiiminaan. Life is a sacred gift, and as First Nations people, there is a sacred responsibility associated with respect and care for the land (Poplar River First Nation et al, 2002, 1). This relationship establishes an ethos of care for one’s community, the land, and all living things which occupy that land alongside them. This may be demonstrated through gibimi-giiwewatoon, the practice of giving something back to the land as part of harvesting, or through ji-gichi-inenimidiyang, the maintenance of good relations with all people. All such practices are tied with mino-bimaadizi, or the pursuit of the good life (Pimachiowin Aki 2022, Keeping the Land).

Evaluation of such concepts is difficult, as the diversity of Indigenous nations globally, and even within the boundaries of Turtle Island, mean that there is no set template or baseline through which an assessment can be made. Maintaining good relations also means recognizing all such communities as equal, which is a challenge to the exceptionalist narrative that outstanding universal value encourages. The 2018 ICOMOS evaluation of the third nomination bid does a better job of outlining this nuance relative to past assessments:

“ICOMOS considers that further studies should be undertaken on the way landscape reflects the important cultural systems that characterise the many indigenous communities of the American sub-Arctic region, before any further sites are considered for nomination.”

(ICOMOS 2018, 26)

The recognition that sites such as Pimachiowin Aki require a distinctions-based lens, which requires careful thought and understanding of regional differences in and between Indigenous nations, is a promising development. Whether this has led to actionable outcomes for similar Indigenous-led nominations and sites remains to be seen.

SUSTAINABILITY

From its inception to its operation, Pimachiowin Aki stands as the embodiment of sustainability. This is embedded into the first tenants of the original accord:

“Our shared vision also acknowledges that we are to protect and take care of the land and resources that the Creator has given us for our survival and well-being.”

(Poplar River First Nation et al, 2002, 1)

Sustainability of the land, particularly for future generations and as part of enacting sacred responsibilities has always been the objective of Pimachiowin Aki, and is encoded through the act of Ji-ganawendamang Gidakiiminaan and through its iteration in the UNESCO World Heritage List (UNESCO 2022). This has since manifested in multiple ways:

Environmental and cultural sustainability: Ecologically and culturally, Pimachiowin Aki is one of the most intact sites representing the boreal landscape in the world. Plantlife residing in the site has been carefully cultivated since time immemorial, maintained through regular site rotations as part of Ji-ganawendamang Gidakiiminaan (ICOMOS 2018, 23). The influence of culture on the ecosystem is also evident through historical cultivation of wild rice (manoomin), which not only enhances the health of freshwater wetlands, but has served as a culturally-tied food dating back at least 12,000 years (ICOMOS 2018, 24).

Biodiversity in Pimachiowin Aki does not merely extend to plants. The site is home to ten species-at-risk and over 300 separate animal species, including three herds of woodland caribou (Pimachiowin Aki Corporation 2022, Fast Facts). The connectivity of nature to culture is demonstrated through the many place names that have been identified by several of the host communities, documenting stories about the landscape and the intimate relationship First Nations hold with them. It is through the practices of maintaining these names that ties to the ancestors are maintained with the stewards of the present (Pimachiowin Aki Corporation 2022, Named Places).

Social and economic sustainability: Despite the sheer size of Pimachiowin Aki, the Pimachiowin Aki Corporation operates on a relatively modest budget. The 2021 Annual Report indicates that the site is maintained in part through a newly-established Pimachiowin Aki Guardians Fund, the Winnipeg Foundation and in part through grants obtained from the Government of Canada, at both the federal and provincial levels (Pimachiowin Aki Corporation 2021, 21). Overall, growth for these funds has been increasing, indicating longer term interest and support from the donor community (Pimachiowin Aki Corporation 2021, 16). What is more difficult to quantify is the true value of the ecosystem services that Pimachiowin Aki provides, but undoubtedly its protection has always been central to its operation.

In order to continue Ji-ganawendamang Gidakiiminaan, it was important to ensure that First Nations stewardship remained a continuous practice. One way in which this is done is through the Pimachiowin Aki’s Guardians Program. Based on a similar program from Environment and Climate Change Canada, Guardians are those responsible for keeping Indigenous knowledge alive while cultivating and monitoring Pimachiowin Aki (Pimachiowin Aki Corporation 2022, Guardians Program). They are responsible for working with knowledge holders and Elders to support good stewardship practices which respect traditional governance and law (Pimachiowin Aki Corporation 2022, Guardians Program). Pimachiwin Aki’s Guardians also play an educational role, reaching out to First Nations youth to ensure that these valuable teachings are passed down to future generations as part of their curriculum (Pimachiowin Aki Corporation 2022, How a Meeting with Hunters and Trappers Led to the Idea for a New School Program).

MEASUREMENT

To evaluate the effectiveness of Pimachiowin Aki as a living heritage site, two metrics have been selected. The first is an assessment of the site against the original agreement it was established under, the Protected Areas and First Nation Resource Stewardship: A Cooperative Relationship Accord. This Accord and its tenants most accurately depict the original core objectives of establishing Pimachiowin Aki as a network of linked protected areas, and as it is sourced directly from the same nations involved with its governance, it is the most appropriate metric of evaluation.

Based on the Accord, the following assessment has been made:

| Terms of Agreement (Poplar River First Nation et al, 2002) | Actions Taken | |

| “3. We recognize and affirm that each of our First Nations has established planning areas for our respective protected area proposals and initiatives. We have established theboundaries of our respective planning areas based on the traplines of the members of ourrespective First Nations.” (2002, 4) | Each member of Pimachiowin Aki has an established land management plan which is available on the main website (Pimachiowin Aki Corporation 2022, Resources). Each plan has a designated area of Pimachiowin Aki, and is implemented with the guidance of their own stewardship boards. Activities are coordinated through conferences with Pimachiowin Aki members, including but not limited to: Elders, youth, women, Guardians and the Directors. Together, this forms the supporting network for Pimachiowin Aki. (Government of Canada 2016, 39-47) | |

| “5. We acknowledge and affirm that it is the Elders and members of each of our First Nations who hold the richest knowledge of our respective planning areas. We affirm that our traditional indigenous knowledge, and the customary resource stewardship through which it is expressed, is vital to the protection and care of our respective planning areas. Wealso affirm that our traditional indigenous knowledge will play a lead partnership role inthe design and implementation of stewardship strategies for protected areas within ourrespective planning areas.” (2002, 4) | The involvement of Elders and youth, the future Elders, is embedded across Pimachiowin Aki’s operations. This is demonstrated through the existence of an Elder and Youth Forum (2016, 47) and through the principles of Ji-ganawendamang Gidakiiminaan. Teachings to uphold these practices, aadizookewin, are transmitted to the community through Elder engagement, which is apparent through the contributions of various Elders directly on the Pimachiowin Aki website (Pimachiowin Aki 2022, Keeping the Land). | |

| “15. We commit to pursuing our relationships with non-aboriginal governments in a respectful and cooperative manner that harmonizes First Nation, provincial and federal responsibilities required to facilitate the realization of our vision of a network of linked protected areas.” (2002, 5) | Partnerships with various non-Indigenous governments have been established and are ongoing. Both the Government of Manitoba and the Government of Ontario are involved in the Board of Directors for Pimachiowin Aki (Pimachiowin Aki 2021, 2). Additionally, Pimachiowin Aki runs an Indigenous Guardians Pilot Program with support from the Government of Canada through an associated joint working group (2021, 5). Academia, UNESCO and conservation networks were also listed (2021, 7-8). The 2021 Annual Report also noted at least 9 other collaborators under Information, Educations and Communications (2021, 12-13), indicating high engagement. |

The second metric of evaluation is the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) from 2007. Of all the existing international charters and declarations that exist, this declaration is the most closely associated with the political and rights-based interests of Indigenous peoples on a global scale and as such is the most appropriate metric for a case study of this nature.

| Objectives | Outcomes | |

| Article 13.1“Indigenous peoples have the right to revitalize, use, develop and transmit to future generations their histories, languages, oral traditions, philosophies, writing systems and literatures, and to designate and retain their own names for communities, places and persons.” (United Nations General Assembly 2007, 12-13) | Pimachiowin Aki is a prime example of First Nations communities taking agency over the stewardship of their traditional territories. The site’s programming touches upon all aspects of cultural revitalization. Notably, both Poplar River First Nation and Bloodvein River First Nation have developed place name maps to ensure the continuity of anishinaabemowin and the associated place-knowledge within Pimachiowin Aki (Pimachiowin Aki Corporation 2022, Cultural Heritage). | |

| Article 29.1“Indigenous peoples have the right to the conservation and protection of the environmentand the productive capacity of their lands orterritories and resources. States shall establishand implement assistance programmes for indigenous peoples for such conservation andprotection, without discrimination.” (2007, 21) | In the case of Pimachiowin Aki, conservation and protection is driven by participating First Nations communities. Arguably, this goes beyond the minimums of the rights outlined through UNDRIP as the leadership of these activities is predominantly Indigenous-led and maintained. The cooperation of provincial governments, and periphery support by the federal government still play a role in ensuring effective collaboration across the network of sites and the development of community capacity to partake in conservation activities. | |

| Article 32.1“Indigenous peoples have the right to determine and develop priorities and strategies for the development or use of their lands or territories and other resources.” (2007, 23) | The journey to Pimachiowin Aki’s World Heritage Site listing was imagined, initiated and implemented by the First Nations stewards associated with those lands. This was demonstrated through the commitment to linking together numerous protected sites that were worthy of international recognition (2002, 4-5). It was important enough that the partnership went through tremendous efforts in order to achieve this inscription and ensure the protection of these lands. Sophia Rabliauskas summarizes this resolution as so: “Each of our First Nation representatives responded [in response to a question about the continuation of the site after its listing] by saying: Pimachiowin Aki is our home, we will care for it, so that our children and grandchildren will havea healthy environment in the future” (Rabliauskas 2020, 13). |

This assessment only offers a glimpse of the immense benefits Pimachiowin Aki has brought to sustainability and heritage conservation. Further analysis has indicated alignment and success across many of the UNDRIP articles and the Accord, and there would be a benefit in exploring this further.

ENDNOTES

1 The land management plans are represented by each member of the Pimachiowin Aki Corporation, but two additional plans from Little Grand Rapids and Pauingassi also exist as a result of their territories overlapping the Ontario and Manitoba border.

WORKS CITED

Books/Book chapters/Journal articles

- Rabliauskas, Sophia. “An Indigenous Perspective: The Case of Pimachiowin Aki World Mixed Cultural and Natural Heritage, Canada” in Journal of World Heritage Studies. Special Issue 2020.

- Singh, J. P. United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) : Creating Norms for a Complex World. New York: Routledge, 2011.

- Watkins, Joe. “From the Inside Looking Out: Indigenous Perspectives on Heritage Values” in Values in Heritage Management: Emerging Approaches and Research Directions. Getty Publications, 2019.

Policies and reports

- Government of Canada on behalf of Pimachiowin Aki Corporation. “Management Plan Appendix I.” Pimachiowin Aki World Heritage Project. UNESCO World Heritage Centre, December 2016.

- ICOMOS. “Advisory Body Evaluation (ICOMOS): Pimachiowin Aki (Canada) No 1415rev” UNESCO World Heritage Centre. UNESCO World Heritage Centre, 2018.

- Pimachiowin Aki Corporation. Annual Report 2021. Pimachiowin Aki Corporation, 2021.

- Poplar River First Nation, Pauingassi First Nation, Little Grand Rapids First Nation and Pikangikum First Nation. Protected Areas and First Nation Resource Stewardship: A Cooperative Relationship Accord. Pimachiowin Aki Corporation, March 2002.

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage: World Heritage Committee Thirty-Seventh Session . WHC-13/37.COM/INF.8B.4, June 17 2013.

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. “37 COM 8B.19 – Decision on Pimachiowin Aki (Canada).” UNESCO World Heritage Centre, 2013.

- United Nations General Assembly. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. September 2007.

Websites

- “Bloodvein River First Nation Supports World Heritage Site Bid.” Edited by CPAWS Manitoba, CPAWS Manitoba, Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, Manitoba Chapter, 22 December 2009. .

- Government of Canada. “The Government of Canada celebrates Pimachiowin Aki as Canada’s first mixed cultural and natural World Heritage site.” Parks Canada, Government of Canada, July 1, 2018. Accessed December 4, 2022.

- Jones, Gord. “Pimachiowin Aki – Canada’s Newest World Heritage Site” in Heritage Matters, Heritage Matters, September 7, 2018. Accessed December 5, 2022. heritage-matters.ca/articles/pimachiowin-aki-canadas-newest-world-heritage-site

- Pimachiowin Aki Corporation. Pimachiowin Aki. Pimachiowin Aki Corporation. Accessed December 4, 2022.

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. “Pimachiowin Aki.”