The Biophilic Design of a Botanical Garden: A Case Study of VanDusen Botanical Garden Visitor Centre in Vancouver

Case Study prepared by Farah Ahmad, Carleton University

Keywords: Sustainability, Botanical Gardens, Biophilic Design, Environmental Education, Heritage

- Lessons Learned

- Description

- Timeline

- Rightsholders and Stakeholders

- Heritage

- Sustainability

- Assessment and Measurement

- Works Cited

PRESENTATION (Download )

This presentation was delivered in class on 8th December 2022. It briefly summarizes the VanDusen Botanical Garden and its Visitor Centre. The presentation showcased the significance of its location, its heritage history, and its role in sustainable development.

LESSONS LEARNED

The various requirements of sustainable certification organizations aim to better the design and construction of buildings today. However, along the way, these requirements put more emphasis on the challenges and influence many design decisions, as seen in the construction of the VanDusen Botanical Garden’s Visitor Centre. There is no doubt that sustainability can take a long time to take effect. That being said, it produces rewarding results, and the effort to build buildings sustainably is the path that must be taken and is, according to Winona LaDuke, “well-worn and green” (LaDuke 3:25). WHile designers are learning how to achieve this, challenging projects such as the VanDusen Botanical Garden’s Visitors Centre will continue to be developed. Adoption of the Visitor Centre’s strategies will help further research and production of alternatives to current practices and effectively narrow the gap. Incorporating cutting-edge modern technologies can bring complexity to a building. The collaboration between various disciplines must happen to gain an understanding of the non-standard systems and how they affect other systems. Typical construction practices are so well embedded into the industry that we automatically use the same products repeatedly without question. For that, the VanDusen Botanical Garden Visitor Centre sets a precedent by asking why such material could or could not be used, its impact on the environment, and whether there are alternatives. Lastly, as demonstrated in the Hamilton case study elsewhere on this site, botanical gardens themselves can be sustainability leaders as they ultimately play a central role in meeting human needs, such as providing green spaces, aiding people’s well-being and developing public educational programming to raise awareness of environmental issues and climate change.

DESCRIPTION

The VanDusen Botanical Garden, located in the heart of Vancouver, British Columbia, was initially founded in 1971. The spectacular 22-hectare Botanical Garden is recognized internationally for its beauty and leadership in plant conservation, biodiversity and sustainability. When it opened in 1975, VanDusen Botanical Garden’s mission was “to awaken an understanding of the vital importance of plants to all life through the outstanding botanical collections, programs, and practices” (“Vandusen Botanical Garden Visitor Centre” Greenroofs). However, in the early 2000s, the Garden’s entrance needed higher visibility, and its existing building structure saw much wear (noting that no information was found on the use or condition of the previous structure). There was also a desire to revitalize interest to attract more visitors, reach a younger demographic and elevate the Garden’s profile internationally. (“Vandusen Botanical Garden Visitor Centre” Greenroofs)

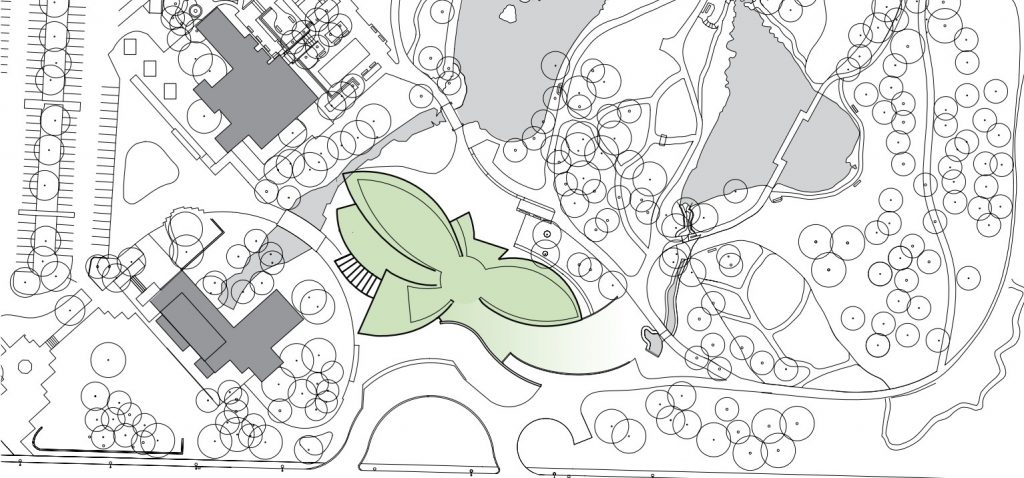

In 2007, Architects Perkins+Will and landscape architect Cornelia Hahn Oberlander were commissioned to design a new Visitor Centre with the objective of increasing the VanDusen Botanical Garden’s visitorship and promoting human-nature interactions, especially within the younger demographic. A lack of facilities to accommodate new needs on the Garden’s grounds combine with the existing buildings’ need for repair formed the basis for discussions on how to develop the new Visitor Centre project for the VanDusen Botanical Garden.

“Flower as Metaphor: A flower is rooted in its own place by harvesting all its own energy and water, by adapting to the climate and site, by operating pollution free, and by promoting health and well-being”

Perkins + Will

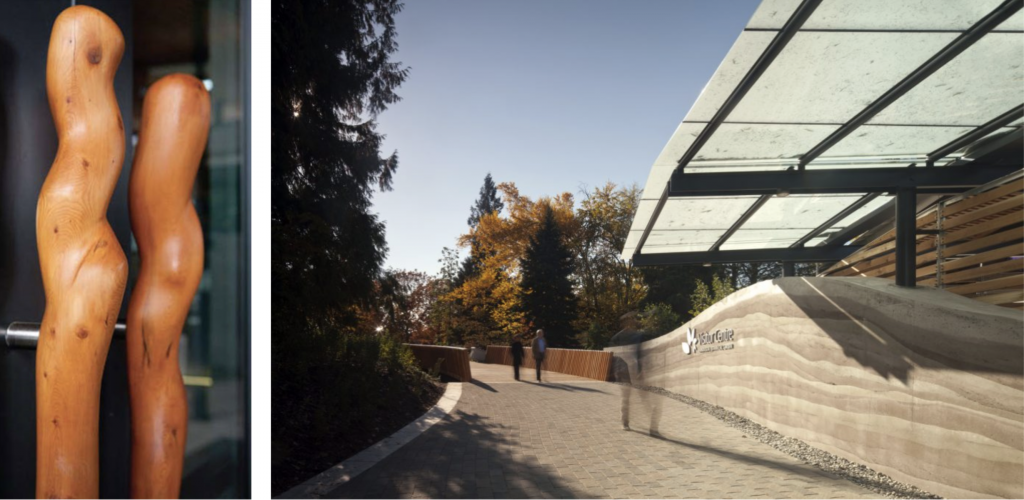

Designed to be one with nature, the Visitor Centre acts as the gateway to the Garden while creating a harmonious balance between architecture and landscape from both a visual and an ecological perspective. The 1,858 m2 single-storey structure is inspired by the organic forms unique to the petal and stem structure of the delicate native British Columbia White Bog Orchid flower. The project’s roof symbolizes undulating green ‘petals’ that float above rammed earth and concrete walls. The vegetated roof undulations representing the petals are connected and blend seamlessly with the ground plane to encourage its use by local wildlife. On the top, these undulations converge at the “oculus,” a skylight feature which tops the central atrium area in the building (“Vandusen Visitor Centre – Wood Works”).

Once in the building, the oculus that metaphors the stem is mounted dramatically overhead. The atrium, with its fully glazed walls, creates a visual interest that inspires visitors and passersby to explore the grounds beyond whilst serving as a transition zone between the gardens and the gathering spaces within the Visitor Centre. The Visitor Centre houses a café, an expanded library, volunteer facilities, a garden shop, office space and flexible classroom spaces for meetings, lectures, workshops and private functions.

The net-zero VanDusen Botanical Garden Visitor Centre is designed to meet the Living Building Challenge (LBC), the most strict set of sustainability requirements in built environments. It received the Living Building Challenge Petal Certificate in 2016 and was one of the first buildings in Canada to receive this certification. The LBC encompasses the LEED Platinum requirements leading the building to receive certification in 2014. The VanDusen Botanical Garden Visitor Centre formally and functionally encompasses the goals of environmentally, socially, culturally, and economically conscious design which will be discussed in detail below (“Case Study: Vandusen Botanical Garden Visitor Centre”).

Despite all the design considerations and sustainability features, there is no record of First Nations being involved in the development of the new centre.

TIMELINE

According to the Vancouver Heritage Foundation, the timeline for the Botanical Garden is as follows:

- 1910: The land was originally a private golf club owned by the Canadian Pacific Railway to encourage wealthy people to settle in the company’s nearby exclusive community of Shaughnessy.

- 1965 – 1966: A group of gardening enthusiasts keen to see a public garden built on the site of the former Shaughnessy Gold Course adopted the idea of creating a botanical garden. They later became the Vancouver Botanical Garden Association.

- 1971: After prolonged negotiations, the Canadian Pacific Railway sold 22.3 hectares for $2.2 million—while keeping the other 4.8 hectares to develop for housing. $1 million was donated by Whitford Julian VanDusen, who was a Canadian lumber magnate, philanthropist, and the Vancouver Foundation founder. He became the garden’s namesake.

- 1975: After four years of development work, the VanDusen Botanical Garden opened to the public on August 30th, 1975. Of the buildings, Herb Wilson of Underwood, McKinley, Wilson and Smith designed the floral hall and garden pavilion; Paul Merrick of Thompson, Berwick, Pratt and Partners designed the forest centre.

- 1977-1996: The curation of the park continued by planting 12,000 trees, flowers and shrubs representing 3,072 species.

- 2007: The Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation, together with the VanDusen Botanical Garden Association, selected the design team of Busby Perkins + Will and landscape architect Cornelia Hahn Oberlander to develop a Master Plan for the Garden.

- 2011: The addition of the Visitor Centre was completed.

- 2014: Received Canada Green Building Council LEED Platinum Certification

- 2016: Received Living Building Challenge Petal Certificate from the International Living Future Institute.

- 2022: The Garden has an administrative staff consisting of approximately 1200 non-gardening volunteers and six full-time gardeners, with seasonal interns assisting during the summer. The Garden’s special features include totem poles, large stone and wooden sculptures, a maze, a Korean Pavilion, a cypress pond and a seasonal heritage vegetable garden. The Gardens also organize special annual events, including the VanDusen Garden Plant Sale and the Festival of Lights in the winter (“Vandusen Botanical Garden” Vancouver Heritage )

W.J. VanDusen at age 85 (left) and then-premier Dave Barrett (right) at the opening of the VanDusen Botanical Garden in Vancouver on Aug. 30, 1975. Photo courtesy of Brian Kent – Vancouver Sun Files

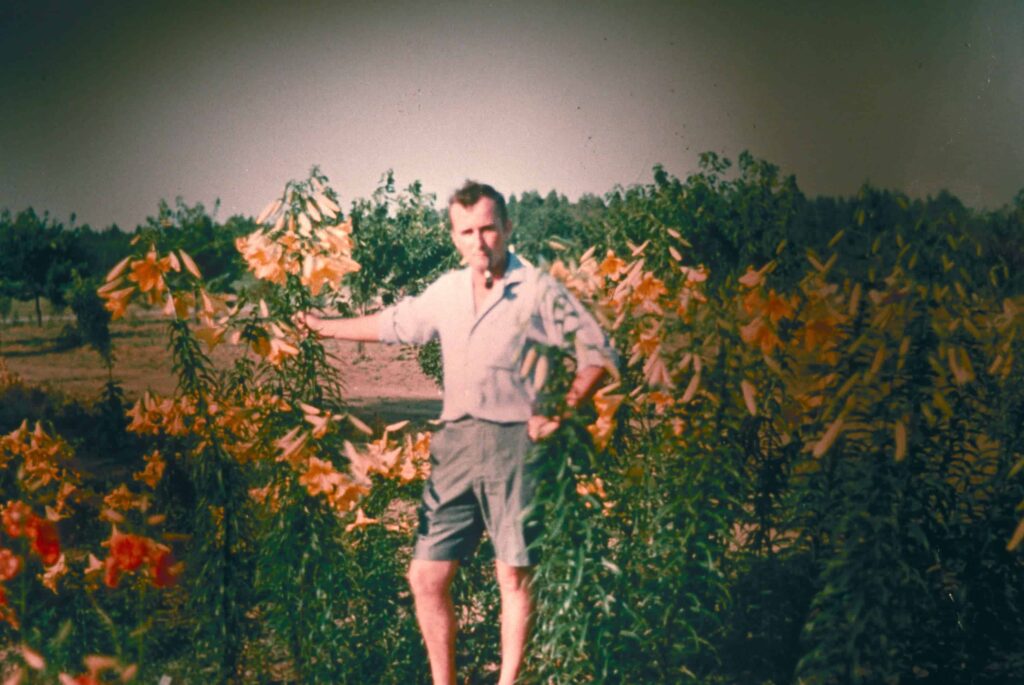

Botanist Roy Forster- Photo courtesy of PlacesThatMatter

Plant curator Roy Foster – Photo courtesy The Province.

RIGHTSHOLDERS AND STAKEHOLDERS

The VanDusen Botanical Garden is located on the unceded Ancestral shared lands of elevent First Nations groups, who are the original inhabitants and make up the Coast Salish people. The Vancouver Botanical Gardens Association acknowledges that the VanDusen Botanical Garden is located on the unceded Ancestral shared lands of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh Nations (“Vandusen Botanical Garden”). These First Nations provide consultation and are invited to give insights about their relationship with plants and nature as they continue to maintain stewardship and live in balance with nature (“Vandusen Botanical Garden”).

Key Organizations:

- City of Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation

- The Vancouver Botanical Gardens Association

- Vancouver Heritage Foundation

Design Consultant:

- Richard Roy Forster (First plant curator of the VBG)

- Garden Caretakers (6 Full-time Members + Seasonal Interns)

- Perkins and Will (Architects)

- Cornelia Oberlander (Landscape architect)

- Morrison Hershfield (Energy consultants)

- Cobalt Engineering (Mechanical & Electrical engineers)

- Fast + Epp (Structural Engineers)

Owners/Rightsholders/Users:

- Musqueam Indian Band

- Squamish Nation

- Tsleil-Waututh Nation

- Government of British Columbia

- Visitors

Sustainability Consultants:

- ARCHITEK Sustainable Building Products

- Raincoast Applied Ecology

For more than 40 years, the VanDusen Botanical Garden has been jointly operated by the City of Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation and the Vancouver Botanical Gardens Association, the city’s charitable non-profit partner. Each organization has its respective responsibilities that have largely stayed the same throughout the history of the Garden. While the Board of Parks and Recreation is responsible for maintaining and managing the facilities and collections, special events, rentals and marketing, the Botanical Gardens Association is responsible for volunteer services, educational programming, running the resource centre and the library at the Garden, the select social media channels and website, and the membership program (“Vandusen Botanical Garden”).

Although the Garden is modest in size, volunteering efforts and financial support from contributors have been key to its advancement, given that a non-profit organization is operating it. Volunteer work includes tending to the gardens, working in the fields, managing the library, educating, and roles in visitor experience, governance, administration and other maintenance and management positions (“Vandusen Botanical Garden”).

Visitor and Membership Services Volunteers – Photo courtesy of VanDusen

School Program Leaders Volunteers – Photo courtesy of VanDusen

HERITAGE

The nature–culture divide is an old dichotomy between humans and the environment. Unfortunately, this notion in modern times continues to be framed by the question of whether the two commodities function separately from one another or if they are in a continuous relationship with each other. Understanding how the nature-culture dichotomy came to be will help policymakers and environmentalists determine a new future in human and nature relations. Accordingly, this analysis aims to break this dichotomy regarding heritage.

While many sources date the inhabitation of the land where the Vandusen Botanical Garden and its Visitor centre are situated to the early 1900s, as noted above, the first known inhabitants of the land are the eleven First Nations that make up the Coast Salish people. During excavation for the landscaping in the late 1900s, workers discovered sea shells, evidence that the land had been under the ocean about 12,000 years ago.

Later, in his curation of the gardens, Roy Forster brought a unique skill set to the design and integrity of VanDusen’s remarkable curatorial collections. In 1999, Forster was made a member of the Order of Canada for his groundbreaking design and exceptional accomplishments at VanDusen. During the time Forster was the plant curator at the VanDusen Botanical Garden, he oversaw the planting of 12,000 trees, flowers and shrubs representing 3,072 species. Today, rivalling the international calibre of botanical gardens, VanDusen is the home of over 7,500 different types of plants from six continents.

Devil’s Club – Photo Courtesy of Herbal Academy

Within the Garden, certain plant species are used as a food source. They are gathered in well-known, well-tended locations by First Nation communities that often stay near these gathering locations for days or weeks to harvest and prepare plants for year-round use. The Garden also houses two ‘story poles’ carved to preserve the local Indigenous knowledge, history and stories. These story poles are preserved as they carry many spiritual values. The two-story poles are the Mosquito Story pole carved by Earl and Brian Muldoe and Al of the Gispudwad by Arthur Sterritt from the Gitxsan Nation. Lastly, The Garden is set within a sprawling network of parkways and an urban context that harmonizes the site’s heritage (“Vandusen Botanical Garden” Vancouver Heritage Foundation).

SUSTAINABILITY

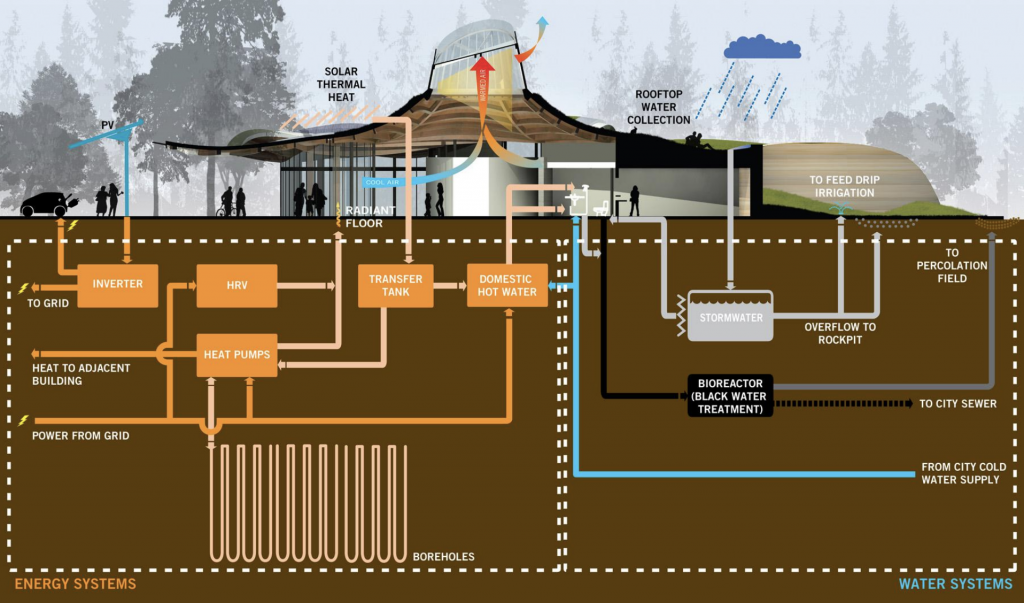

Environmental Sustainability: The VanDusen Botanical Garden Visitor Centre is designed to exceed LEED Platinum standards and achieve recognition for the Living Building Challenge requirements. The Visitor Centre uses natural and mechanical systems together to create a building with a low environmental impact by reusing the site’s renewable resources and the building’s waste. Collectively, the design addresses seven sustainability performance areas: Site, Water, Energy, Materials, Equity, Health and Beauty (“Vandusen Botanical Garden Visitor Centre” International Living Future Institute)

- Site: By analyzing the garden’s ecology, the project’s team was able to situate the visitor centre seamlessly into the natural landscape, avoiding the destruction of rare trees, shrubs and plants around the structure. The building’s green roof also attracts native fauna to access the roof’s ecosystem. (“Vandusen Botanical Garden Visitor Centre” International Living Future Institute)

- Water System: 100% of the water used comes from captured precipitation or reused water. Rainwater is collected, treated and reused for the centre’s grey-water needs. Moreover, blackwater is also treated by an on-site bioreactor and used to water the garden. (“Vandusen Botanical Garden Visitor Centre” International Living Future Institute)

- Energy System: The Visitor Centre is designed to use on-site, renewable systems to achieve net-zero energy requirements. It generates enough energy to offset its own uses on an annual basis. The various features that help achieve the net zero energy requirements are the following:

- Photovoltaic (PV) panels are designed to provide 11,000 kWh of power to the Visitor Centre.

- Four hundred solar hot water tubes produce thermal energy and store them in 50 geo-exchange boreholes. This thermal energy is used for heating the building’s water.

- A green roof provides added insulation for the building, and a solar chimney composed of an operable glazed oculus provides natural ventilation. The solar chimney also features an aluminum heat sink, which converts sunlight into convection energy, providing air movement through the space.

- Daylight and views are maximized through large areas of glazing. 93% of daylighting is at levels that allow lights to be off during daylight hours, while 85% of spaces have outdoor views. As for the evenings, light levels are optimized according to the spaces’ occupancy (“Vandusen Botanical Garden Visitor Centre” International Living Future Institute).

- Materials: Careful attention was given to material selection that requires less maintenance over the life of the building. Perkins+Will chose materials according to their health, carbon footprint, recycling ability, and individual life cycles.

- The Visitor Centre uses wood as the primary building material as it sequesters enough carbon to achieve carbon neutrality. Wood products are used extensively in the panelized roof structure to the cladding, furnishings, millwork and wall finishes.

- Another key imperative regarding the enclosure’s material is the locally sourced materials used to build the rammed earth walls. Primarily chosen for its potential for high insulating value, the idea of sourcing locally further solidified the choice to build rammed-earth walls at the Visitors Centre. Rammed earth is the process that takes the native soil from the site and combines it with approximately 10% cement and other admixtures, and then rams it into place against formwork (“Vandusen Botanical Garden Visitor Centre” International Living Future Institute).

Socio-Cultural Sustainability: Since 1975, Vandusen Botanical Garden and its later addition, the Visitor Centre, have been connecting its visitors to nature while promoting environmental knowledge and willingness to engage in sustainability actions. Discussed below are some themes that contribute to socio-cultural sustainability:

- Affordability, availability of amenities that facilitate inclusion and access, way-finding, and non-educational signage provide an equitable garden for all where nature has beneficial effects on well-being, cognition, and behaviour.

- Events, family memory making, volunteerism, and the connection between people to plants and nature, create a sense of community and connectives.

- Advocating climate change issues, Indigenous reconciliation and animal welfare, planting and protecting Indigenous plant collections, promoting ecology, and practicing sustainability are all ways responsible socio-cultural stewardship is present at the Vandusen Botanical Garden.

- Educational opportunities such as educational programmes and youth and family engagement contribute to and promote a social understanding of the balance between human activities and natural ecosystems (“VanDusen & Bloedel Strategic Plan”).

Economic Sustainability: The Vandusen Botanical Garden Visitor Centre construction and its sustainability features had high front-end costs, but which over the long term, should be most economical. The Wood First Act passed in 2009 by the provincial government of British Columbia, is the primary driver that led to the extensive use of wood products in construction. The Act mandates that all new publicly-funded buildings utilize wood as the primary building material. The idea is to support the provincial lumber industry and the communities that depend on it by generating a higher demand for wood products leading to economic growth (Lemieux 6).

ASSESSMENT AND MEASUREMENT

The United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide a framework to understand and evaluate The VanDusen Botanical Garden and the Visitor Centre’s contribution to sustainability. Arguabley the Vandusen Botanical Garden and Visitor Centre can contribute in one way or another to all 17 of the SDGs. This is a consequence of Botanical Gardens aligning their actions to the SDGs since their work is closely tied to public education, climate action, plant conservation, and sustainability. However, this assessment considers only three targets that are part of the three SDGs the Garden contributes to the most: Goal 4—Quality Education, Goal 12—Responsible Consumption and Production and Goal 15—Life on Land.

| UN – SDG | UN – SDG Targets | VanDusen Botanical Garden Contribution | Potential Metrics/Metrics |

| Target 4.7 – Education for Sustainable Development and Global Citizenship | Delivers educational experiences that raise awareness linking plant conservation and cultural diversity. Installs interpretive signage to include indigenous knowledge & languages as well as people with disabilities. | Percentage of participants on educational experiences Percentage of users/visitors who are either from Indigenous Communities or/and people with disabilities. |

| Target 12.2: Sustainable Management and Use of Natural Resources | Promotes the sustainable use of natural resources by transitioning towards clean and sustainable energy sources. | The total annual electrical energy consumption for the building is 119 kwh/sm-yr, a 66% reduction over the reference building. |

| Target 15.5: Protect Biodiversity and Natural Habitats | The Visitor Centre is integrated into the environment avoiding the destruction of the ecosystems and natural habitats. Collaborations to advance plant conservation and the protection of wildlife. | Percentage of plant and animal species. |

Similarly, to some degree, the Garden and the Visitor Centre can meet all 20 imperatives outlined by the Living Building Challenge. However, in this assessment, the top two imperatives, which fall under the material category within the Living Building Challenge and the LEED scorecard are outlined.

| Living Building Challenge Petal | Imperative | VanDusen Botanical Garden Contribution | Potential Metrics |

| Material | Imperatives 10 – Red List | The Red List is a list of currently 14 chemicals that must not be used in the building due to their links to severe negative effects on the environment and/or health. In the construction of the new Visitor Centre, the design team did not use any material that consists of any of these chemicals in any whole assembly to the smallest of components (Lemieux). | Percentage of environmental issues caused by the toxic material (should be diminished) Percentage of health issues caused by the toxic material (should be diminished) |

| Material | Imperatives 13 – Appropriate Sourcing | Appropriate Sourcing provides maximum travel distances for various contributors to the project. In the construction of the new Visitor Centre, the maximum travelled distance for consultants was within a 2,500 km radius from the project. Additionally, high-density materials came from within a 500 km radius (Lemieux). | Percentage of carbon footprint realized during the construction. |

LEED SCORE CARD (New Construction and Major Renovations) “The VanDusen Botanical Garden Visitor Centre.” Canada Green Building Council.

| LEED Criteria | Points/Level |

| Certification Level | Platinum |

| Total Points Earned | 54 |

| Sustainable Sites | 10 out of 14 |

| Water Efficiency | 5 out of 5 |

| Energy & Atmosphere | 15 out of 17 |

| Materials & Resources | 6 out of 14 |

| Indoor Environmental Quality | 13 out of 15 |

| Innovation in Operations | 5 out of 5 |

In an age of the biodiversity crisis and the climate emergency, sustainability and, in particular, the Sustainable Development Goals can help re-imagine the role of botanical gardens. However, it is also essential to note that the SDGs lack focus on Indigenous Rights. They focus on inclusive economic growth but overlook power structures that increase inequalities and pressures on natural resources. This negligence exacerbates biodiversity loss and climate change and results in social tensions. For that reason, alternative education that emphasizes planetary ethics and degrowth, as well as education on alternative paradigms such as Indigenous learning, and circular economy, is vital in this modern world we live in. Leaders in environmental education, such as Botanical gardens, can incorporate alternative worldviews and systemic thinking into their educational programs. They are where concepts may be sow sowed to germinate in the broader community.

WORKS CITED

Books/Book chapters/Journal articles

- Author. “Botanic Gardens and Their Contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals.” Journal of Botanic Gardens Conservation International, date. https://www.bgci.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/BGjournal%2015_1.pdf.

- Kellert, Stephen R., et al. Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life. John Wiley & Sons, 2008.

- Lemieux, Catherine. How the Current Sustainability Movement Impacts the Enclosure: A Look at the VanDusen Botanical Garden Visitors Centre.

- Zelenika, Ivana, et al. “Sustainability Education in a Botanical Garden Promotes Environmental Knowledge, Attitudes and Willingness to Act.” Journal title. Taylor & Francis, 2018, pp..

Policies and reports

- Alec, Geronimo. “First Nations Heritage and Vandusen Botanical Garden Collections.” Erica Notebook.

- Annual Report 2021. Vandusengarden.org.

- Lopez-Villalobos, Adriana, et al. “Aligning to the UN Sustainable Development Goals: Assessing Contributions of UBC Botanical Garden.” MDPI, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 21 May 2022, .

- Palibroda, Duane. “VanDusen Botanical Gardens Visitor Centre.” Wood Works, Dec. 2012.

- Szeleczky, Olivér Lóránt, and Shizuka Sasaki. “Vandusen Botanical Garden Visitor’s Centre and Green Roof.” Spacing, Apr. 2014.

- Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation. “VanDusen & Bloedel Strategic Plan.” Park Board Meetings, 7 Oct. 2021.

- “Vandusen Visitor Centre – Wood Works.” Canadian Wood Council.

Websites – need to pull out image credits and move to captions.

- Berrisford, Michael. “Vandusen Botanical Garden Visitor Centre: Trim Tab.” Trim Tab Online Magazine, 12 May 2016.

- “Case Study: Vandusen Botanical Garden Visitor Centre.” BKL, https://bkl.ca/projects/vandusen.

- Greenroofs.com. “Vandusen Botanical Garden Visitor Centre – Featured Project.” YouTube, YouTube, 10 Aug. 2021.

- Griffin, Kevin. “This Week In History: 1975 From Golf Green to Garden Green, VanDusen Botanical Garden Made Its Mark on a City.” Vancouversun.

- “LEED Spotlight: The Vandusen Botanical Garden Visitor Centre Certifies LEED Platinum.” Canada Green Building Council (CAGBC), 30 Mar. 2022, .

- “Overcoming the World’s Challenges.” The Global Goals, 12 Dec. 2022,

- TEDxTalks. “Minobimaatisiiwin – The Good Life | Winona LaDuke | Tedxsitka.” YouTube, YouTube, 3 Sept. 2014, .

- TheVancouverGuy. “Totems.” Flickr, Yahoo!, 24 Mar. 2013.

- “Vandusen Botanical Garden Founding Director Passes Away.” VanDusen Botanical Garden Founding Director Passes Away | American Public Gardens Association, .

- “Vandusen Botanical Garden.” VanDusen Botanical Garden, .

- “The VanDusen Botanical Garden Visitor Centre.” Canada Green Building Council (CAGBC), .

- “Vandusen Botanical Garden Visitor Centre.” Greenroofs.com, 9 Nov. 2021.

- “Vandusen Botanical Garden Visitor Centre.” International Living Future Institute, 21 Sept. 2022.

- “Vandusen Botanical Garden Visitor Centre.” International Living Future Institute, 1 Aug. 2022.

- “Vandusen Botanical Garden Visitor Centre: Perkins&Will.” Archello.

- “Vandusen Botanical Garden • Vancouver Heritage Foundation.” Vancouver Heritage Foundation, 23 Aug. 2017, .

- “Vandusen Botanical Garden: Visitor Centre: Community + Recreation, Hotels + Tourism Wood Design + Construction: Naturally:Wood.” Naturally Wood, 11 May 2022, .

- Vinnitskaya, Irina. “Vandusen Botanical Garden Visitor Centre / Perkins+Will.” ArchDaily, ArchDaily, 20 Mar. 2012, .

- Wolfe, Devon. “Vandusen Botanical Garden Visitor Centre.” Perkins&Will, 10 Feb. 2021, .

- Zia, Sumra. “Botanical Gardens As Sustainability Leaders.” Sustainable Heritage Case Studies, 7 Feb. 2022.