Renewable Energy in Tourism: Repurposing the Abandoned Industrial Town of Val-Jalbert, Quebec

Case study prepared by Kaleigh MacLeod, Carleton University

Keywords: Industrial Heritage Tourism, Adaptive Re-Use, Pulpwood Industry, Renewable Energy and Hydroelectric Generating Station.

LESSONS LEARNED

In the twentieth century, the province of Quebec prospered in the pulpwood industry and became recognized worldwide for its resources (Canada’s Historic Places, n.d., para. 2). After years of neglect the Quebec City Tourism purchased the industrial site of Val-Jalbert to convert the existing infrastructure into a tourist destination (Canada’s Historic Places, n.d., para. 5). Over the years, the park made many efforts to restore the existing buildings and streetscapes to attract visitors (Val-Jalbert, n.d.). While the park carefully executed work on the fragile state of the existing buildings, it was very important that new development not interfere with the overall image of the town and that visitors could differentiate between old and new structures.

The construction of a new hydroelectric generating system is an excellent example of a new development within the original context. This station has many sustainable aspects that benefit the industrial town and other nearby municipalities. A list of sponsors confirm that the project served the following local municipalities: Pekuakamiulnuatsh Takuhikan, the regional county municipality of Maria-Chapdelaine and Domaine-du-Roy, and the municipality of Chambord. Pekuakamiulnuatsh Takuhikan, a political and administrative organization of Pekuakamiulnuatsh First Nation residing in Mashteuiatsh, holds the share majority for the hydroelectric generating station (Moar, 2013, para. 6). The Pekuakamiulnuatsh First Nation chief, Clifford Moar, states: “The Val-Jalbert project, along with other recent development projects, are an important opportunity for the Mashteuiatsh community to develop and take control of its future. This project is beneficial in terms of socio-economic development for a community that aims for greater political and financial autonomy and harmonious cohabitation with its community (Moar, 2013, para. 5).” The above points have argued for the economic and socio-cultural pillars of sustainability, but the environmental sustainability of the renewable energy produced in a power plant is also understood.

PRESENTATION

The sustainable heritage case study assignment was divided into three sections: proposal, presentation and final written submission. The presentation was completed prior to the final deliverable to provide the students with guidance and feedback for the upcoming section. The attached PowerPoint document was presented to the class on November 14th, 2019.

DESCRIPTION

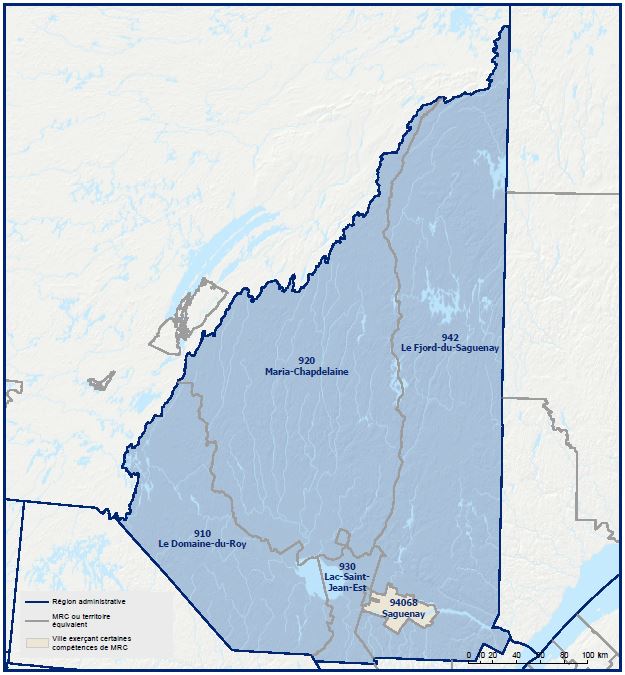

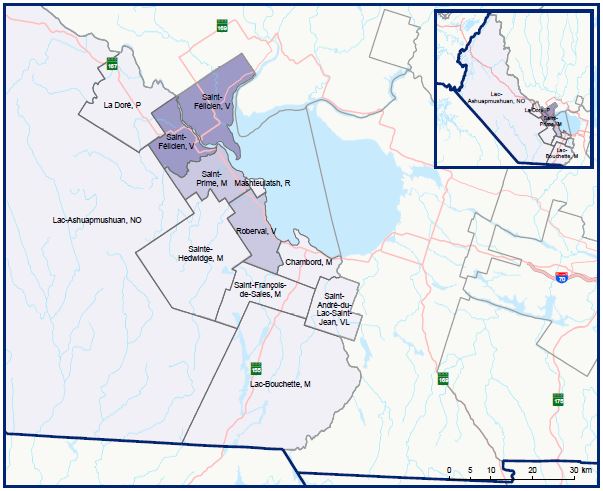

The industrial town of Val-Jalbert is sited in the regional county municipality (RCM) of Domaine-du-Roy of the Saguenay Lac-Saint-Jean administrative region (Figure 1) (Parks Canada, 2019, para. 2). More specifically, the town is located within the municipality of Chambord, Quebec (Figure 2) (Parks Canada, 2019).

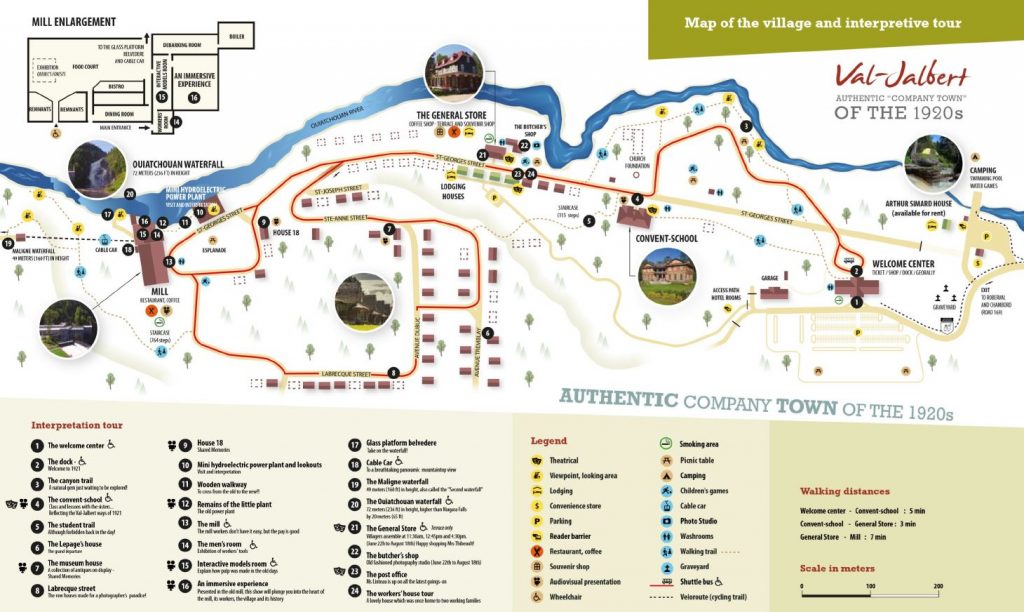

Established in 1901, the town built a pulp mill for the increasing demand in newsprint paper in American and British markets (Canada’s Historic Places, n.d., para. 2). The town strategically borders the Ouiatchouan River, from the Maligne Waterfall to its mouth, for the extraction of hydraulic energy from water currents (Canada’s Historic Places, n.d.). In the twentieth century, it was not unusual for mechanical pulp and paper industries to be erected against constant water streams to harness energy for the mill’s operation (Figure 3) (Canada’s Historic Places, n.d., para. 4). The province of Quebec turned to hydroelectric energy as an alternative to other non-renewable energy, such as coal, oil or gas (Courville, 2008, p. 191).

The town underwent multiple ownership changes; the reoccurring dilemma of expanding and upgrading the plant was financially overbearing on each of the owners until Val-Jalbert eventually declared bankruptcy in 1942 (Répertoire du Patrimoine Culturel du Québec, n.d.).

Under management of Chicoutimi Pulp Company, the mill experienced its first closure on May 16, 1924 (Val-Jalbert, n.d.). Later, the Quebec Pulp and Paper Mills, gained control of the Compagnie de Pulpe et de Pouvoirs d’Eau du Saguenay and its subsidiaries, including Chicoutimi Pulp Company (n.d.). The pulp mill continued to operate for another year until it ceased production indefinitely (n.d.). The Quebec Pulp and Paper Corporation acquired the property until the Quebec government expropriated the site (n.d.). Following the mill’s definitive closure, most residents had left with the exception of a dozen families who had grown attached to the site and tried to keep it going (Gagnon, n.d.).

The Quebec City Tourism acquired the industrial town of Val-Jalbert after many years of inactivity (Canada’s Historic Places, n.d., para. 5). During the process of designation, the Ministry of Culture and Communication identified ninety-four buildings and ruins including a few homes, the hotel, the general store, the school and the pulp mill (Gagnon, n.d.). The town is recognized for its impressive urban planning practices where Gagnon (n.d.) stated: “Through the alignment of streets, the division of properties and the structuring of institutional and commercial space, as well as by the quality of existing building stock of American vernacular influence, the striking features of the site attest to the unique character of this industrial village (Author’s translation).” Divided into two sectors, the upper and lower town, the site delineated the residential from the industrial, commercial and intuitional activities respectively (Canada’s Historic Places, n.d., para. 3).

Many adaptive re-use projects were conducted to preserve the existing building stock and transform the facility into a tourist destination. The restoration and development of trails, stairs and local roads were completed and basic services such as aqueduct and sewage networks and electricity within the town were repaired (Val-Jalbert, n.d.). Following the initial preservation efforts, the town welcomed tourists to visit the abandoned site of Val-Jalbert. There have been numerous renovations since the opening of the tourist destination; the projects include the mill, school, church, hotel and a few houses (Val-Jalbert, n.d.).

The tourist destination offers different accommodation possibilities: there are 188 campsites and mini cottages with a variety of service options (Val-Jalbert, n.d.). When visiting the industrial town, there is a panoply of activities available (Val-Jalbert, n.d.):

- Animation

- Look-outs

- Guided tours

- Expositions

- Geo-rally

- Nature hikes

- Cable car

- Pulp mill and mini power plant

The industrial town of Val-Jalbert prides itself on heritage and natural values, just as their mission statement (Val-Jalbert, n.d.) articulates, “Operate, protect, develop and exhibit in a sustainable way the industrial town of Val-Jalbert where its interest lies in the history, heritage and natural environment (Author’s translation).”

There has been much controversy regarding the addition of a hydroelectric generating station at Val-Jalbert. The Quebec government planned on reducing the flow rate to 0.3m3 per second, but the heritage council repeatedly stated that the proposed flow rate would dry out the waterfall (Shields, 2013, para. 2). The Quebec government authorized construction of the power plant with a revised 0.7m3 per second during periods of visit and 0.3m3 per second during the off season (Shields, 2013, para. 7). The RCM of Domaine-du-Roy united with other groups, namely Pekuakamiulnuatsh Takuhikan and the RCM of Maria-Chapdelaine for the development of a project that will produce electricity for Hydro-Quebec (Regional County Municipality [RCM] Domaine-du-Roy, n.d., para. 3). Each partner receives an economic return of $90 million over a twenty-five-year period (Val-Jalbert, n.d., para 7). The industrial town of Val-Jalbert receives $19.8 million over a forty-year period, which will contribute to the repair and maintenance of the town (Val-Jalbert, n.d., para. 8).

TIMELINE

Full dates are included where they were available.

Archeologists found Native American and European-Quebec traces on the designated site of Val-Jalbert (Canada’s Historic Places, n.d., para. 5).

Industrial town timeline

- April 27, 1901 – Damase Jalbert founded Ouiatchouan Pulp Company (Val-Jalbert, n.d.)

- 1902 – construction of the pulp mill and the Ouiatchouan hydroelectric dam was completed and operation commenced (Val-Jalbert, n.d.)

- March 31, 1904 – Damase Jalbert passed away and the industrial town was acquired by Ouiatchouan Falls Paper Company (Val-Jalbert, n.d.)

- 1907-1914 – the development of the town proved costly and the American shareholders sold shares of the company to Julien-Edouard-Alfred Dubuc of Chicoutimi Pulp Company (Val-Jalbert, n.d.)

- 1913 – originally called Ouiatchouan, the town adopted the new name of Val-Jalbert (Répertoire du Patrimoine Culturel du Québec, n.d.)

- 1915 – a new plan for the town was commissioned by the Quebec government (Répertoire du Patrimoine Culturel du Québec, n.d.)

- May 16, 1924 – the pulp mill paused its operation due to administrative setbacks (Val-Jalbert, n.d.)

- December 9, 1925 – the pulp mill continued operation under the management of Quebec Pulp and Paper Mills (Val-Jalbert, n.d.)

- August 13, 1927 – the mill permanently stopped the production of pulpwood products (Val-Jalbert, n.d.)

- November 30, 1927 – Quebec Pulp and Paper Corporation acquired the property (Val-Jalbert, n.d.)

- 1930 – the church bell was removed and installed in the nearby Saint-Eugene church (Gagnon, n.d.)

- October 19, 1942 – Quebec Pulp and Paper Corporation declared bankruptcy as it never paid its share to the Quebec government for the development of a reservoir at Lake Kenogami (Répertoire du Patrimoine Culturel du Québec, n.d.)

Tourist destination timeline

- 1960-1986 – Quebec City Tourism managed the town and initiated restorations, renovations and new development projects (Val-Jalbert, n.d.)

- June 24, 1963 – the abandoned industrial town opens to the public as a tourist destination (Gagnon, n.d.)

- 1987 – the site was sold to la Société des établissement de plein-air du Québec (SEPAQ) (Val-Jalbert, n.d.)

- 1996 – the entire site of the industrial town of Val-Jalbert, architecture and landscape, was formally recognized by the Canadian Register of Historic Places (Canada’s Historic Places, n.d.)

- 1998-2009 – the RCM of Domaine-du-Roy joined SEPAQ in 1998 (Val-Jalbert, n.d.) but became sole proprietor in 2009 (Répertoire du Patrimoine Culturel du Québec, n.d.)

- Autumn 2009 – the hydroelectric project on the Ouiatchouan River was launched and public consultations were organized to include the population in the project (Val-Jalbert, n.d., para. 10)

- November 24, 2011 – Val-Jalbert wins a Canadian tourism award for touristic experience of the year (Val-Jalbert, n.d.)

- December 2012 – the sponsors for the Hydroelectric project received government permission to commence construction (Val-Jalbert, n.d.)

- February 24, 2012 – three more Canadian tourism awards were given to Val-Jalbert for personality of the year, 50 000 visitors and best website (Val-Jalbert, n.d.)

- February 6, 2015 – the construction is completed and the hydroelectric generating system is in operation (Val-Jalbert, n.d.)

STAKEHOLDERS

Organizations: A few organizations that had a toll in the town’s conversion include the Quebec government, the Ministry of Natural Resources, Quebec City Tourism and Société des Établissements de Plein Air du Québec (SÉPAQ). Others that had an influence on the construction of the hydroelectric generating station include: Société Énergie Hydroelectrique Ouiatchouan whose sponsors were Pekuakamiulnuatsh Takuhikan, the regional county municipality of Maria-Chapdelaine and Domaine-du-Roy, and the municipality of Chambord (Groupe Pek, Val-Jalbert, n.d., para.4). In addition, Conseil du Patrimoine Culturel du Quebec (CPCQ), had an important role in defending the integrity of the natural appearance of the Ouiatchouan waterfall during the proposal of a hydroelectric generating station (Shields, 2013, para. 9). Finally, the Ministry of Culture and Communications should also be mentioned under this section for their work in the designation of the heritage site (Répertoire du Patrimoine Culturel du Québec, n.d.).

Owners/ users: Over the years, there have been countless changes in ownership which are increasingly evident when observing the timeline. The regional county municipality of Domaine-du-Roy in the Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean region of Quebec became the sole proprietor of the tourist destination in 2009 (Répertoire du Patrimoine Culturel du Québec, n.d.). The users include staff members, maintenance crew, and visitors of course.

Consultants: The architecture firm commissioned for the design of the hydroelectric station was Atelier Pierre Thibault (see figure 5) (Mairs, 2016). The design team included Pierre Thibault, Jerome Lapierre and Mathieu Leclerc (Mairs, 2016). Another consultant was Génétique, an engineering, manufacturing and construction company, mandated to design electrical, protection and control and monitoring aspects of the Val-Jalbert hydroelectric station (Génétique, n.d.)

HERITAGE

The town of Val-Jalbert was recognized August 8, 1996 for its heritage value through the site’s interest in the province’s industrial and economic history, in urban development of the industrial town and the relationship to the surrounding environment (Canada’s Historic Places, n.d.).

Natural heritage: As it was very common for an industrial town to harness energy from water currents, it is no surprise that the pulp mill was located against the Ouiatchouan river (Canada’s Historic Places, n.d., para. 4). Additionally, its location within the forestry sector provided a supply of natural resources for the processing of pulpwood products (Canada’s Hisotric Places, n.d.). Without the surrounding landscape, the industry could not function in the same way, therefore the natural heritage is intrinsic to the industrial site.

Cultural heritage: There is an unfortunate negative connotation related to the remnants of the industrial age. In his chapter, Massimo Preite wrote: “Beginning in the 1990s, industrial cities faced a new cycle of transformations which, unlike the renewals of previous years, saw abandoned production and manufacturing sites not as obstacles to be removed but as opportunities for development” (Preite, 2013, p.101). This shift in perspective no longer considered the conservation of industrial buildings and landscapes as “redundant and uneconomical” (Xie, 2015, p.6). The United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO, 2013) mentioned that industrial heritage sites are valued because ‘industrial sites are important milestones in the history of humanity, marking humankind’s dual power of destruction and creation that engenders both nuisances and progress’ (as cited in Xie, 2015, p.2). Not only is the industrial heritage valuable but there are many sustainable benefits to industrial heritage conservation, which will be discussed in the sustainability section of this essay.

The value of conserving the industrial heritage in Val-Jalbert was recognized and a new program, industrial tourism, was proposed to be implemented. In his text, Industrial Heritage Tourism, Wolfgang Ebert explains: “The preservation of industrial monuments no longer appears as a cultural luxury but as a necessary expenditure that promises good economic return” (Ebert, 2013, p.202). The industrial town of Val-Jalbert, is an example of industrial monuments making a profitable income from tourism. The pulpwood industry at Val-Jalbert experienced economic hardships in the past, but it has found a new income-generated use for the site.

When Quebec City Tourism acquired the land, the organization contacted René Bélanger, the engineer that arrived in Val-Jalbert in 1927 (Gagnon, n.d.). He was hired for his knowledge and expertise in the history of the pulpwood industry (Gagnon, n.d.). There was obviously an attempt to project an authentic experience for all who visited the site.

In the first chapter, The Scope of Industrial Heritage Tourism, the author cautions that industrial heritage tourism can be faced with the potential for both problems and opportunities when maintaining a site’s historical identity and the spirit of the past (Xie, 2015, p. 5). Rising concerns with authenticity and commodification in industrial heritage tourism can result from transforming industrial landscapes into aesthetic spaces for recreation and entertainment (Xie, 2015, p. 5). The industrial town of Val-Jalbert made an effort to accurately portray the lifestyles of the citizens and the urban context through consultants. Additionally, new development was designed in respect to the industrial heritage context while ensuring that modern construction could be easily discerned from the original buildings.

SUSTAINABILITY

The industry might not have been sustainable while it was running, but this fact should not prevent the heritage conservation of an industrial site. As Benjamin Fragner explained in his text, Adaptive Re-use: “Every mill in the past affected its environment directly and indirectly and left an ecological footprint” (Fragner, 2013, p. 142). Regardless of the harmful consequences related to the operation of various industries, it would be equally harmful to demolish the existing industrial building stock rather than recycling. There is also an opportunity to “reflect upon the pollution and destruction of our environment, social and economic changes, our changing perception of technology and the debates concerning priorities in society” (Fragner, 2013, p. 142). In doing so, the visitors learn about the wonderful aspects of the industrial age while being aware of the negative impacts it held as well.

When the proposal for a hydroelectric generating station in the industrial town was announced, community members and organizations voiced their concerns. There was a debate on the subject that indicated the inherent consequences of a hydroelectric generating system in relation to the heritage site’s authenticity (Shields, 2013, para. 9). Large players in the debate included the heritage council, Conseil du Patrimoine Culturel du Quebec (CPCQ), arguing for the preservation of the Ouiatchouan waterfall flow rate (Shields, 2013).

It seems that the Quebec government and the community arrived at a compromise. With the operation of the hydroelectric generating system commencing in 2015; a portion of the profits generated by the sale of electricity will be utilized to maintain the industrial town of Val-Jalbert (Val-Jalbert, n.d., para. 8).

Environmental sustainability: The heritage council was worried that the Quebec government’s revised flow rate of 0.7m3, although improved from the previous 0.3m3 per second, was still not sufficient (Shields, 2013, para. 9). The article wrote, “In the summer, the flow can vary between 12 and 20m3 per second (Shields, 2013, para. 7).” Therefore, the flow rate is still reduced significantly from its original rate.

The concerns for the construction of a hydroelectric generating system affecting the tourist destination might be valid, but the implementation of such a system can have positive impacts on the site as well. The renewable energy produced from hydroelectricity is sustainable in that it aims at minimizing climate change through mitigation (Sæþórsdóttir & Hall,2018, p. 1).

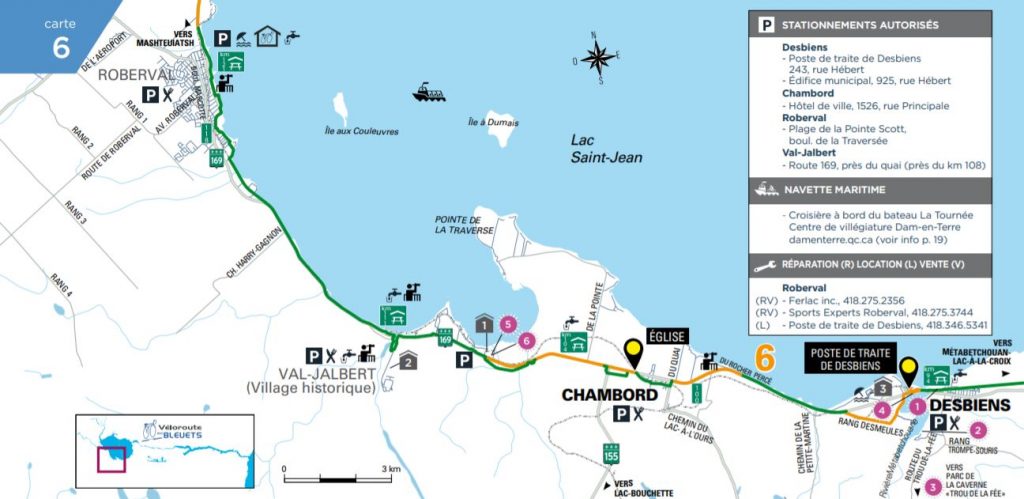

A few green initiatives were implemented on the town’s premises and surrounding landscapes. The first was an electric charging station recently installed at the welcome center (Val-Jalbert, n.d.). The second is a network of bike lanes (Figure 6), called Véloroute des Bleuets, with lanes across the Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean region, including Val-Jalbert (Véloroute des Bleuets, n.d.). The Regional Parc has proven that they are committed to offering an amazing experience during a visitor’s stay at Val-Jalbert with a number of useful services.

Social sustainability: The industrial town of Val-Jalbert is making an effort to preserve the cultural setting of the abandoned town. Their goal is to welcome visitors and educate them on the livelihoods of the community that lived in this industrial town.

The power plant is a prominent source of energy for the province of Quebec because other energy sources are mostly inaccessible (Courville, 2008, p. 271). In Serge Courville’s book, Quebec: A Historical Geography, he wrote: “Following the Second World War, Quebec entered a new phase of growth, led this time by expansion in the mining and forest industries with massive hydroelectric power projects and brand-new towns” (Courville, 2008). Therefore, the hydroelectric production of electricity speaks to the landscape of the province of Quebec and helps to form a provincial identity.

Economic sustainability: While the town was quickly declining as a result of the mill’s closure, another means to support to town was required. The transformation of the town into a tourist destination allowed for the story of this industrial site to be shared with the public.

Another revenue for the industrial town is the compensation from the hydroelectric generating system. (Val-Jalbert, n.d., para. 7). The system will be beneficial as the Regional Parc plans to receive appropriate economic benefit for housing the Hydroelectric generating station next to the Ouiatchouan River and pulp mill (Val-Jalbert, n.d., para. 8). In the article, Floating away: The impacts of hydroelectric power stations on tourists’ experience in Iceland, Sæþórsdóttir wrote: “It is generally assumed that power plants and accompanying infrastructure reduce the attractiveness of nature-based tourism destinations. Therefore, opposition against power plant development can be expected and it is often greater in natural areas which possess a high-quality landscape, than at destinations where developments are already in place (Sæþórsdóttir & Hall,2018, p. 1).” To summarize, a hydroelectric generating system is often considered intrusive and unattractive in a touristic natural setting, but the author argued that visitors aren’t bothered by these types of development (Sæþórsdóttir & Hall,2018, p. 30).

The plans for the power plant were conceived with a goal of creating new lookouts on the structure’s roof and a new interpretive program was developed inside (Val-Jalbert, n.d., para. 5). The industrial town of Val-Jalbert incorporated the power plant in a respectful manner to combine old and new development.

Sustainable development goals: It can be argued that the industrial town of Val-Jalbert is subject to all the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). For the purpose of the essay, three goals related to the themes of this essay will be discussed in further detail:

- Goal 7 – Affordable and clean energy: ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all.

- Goal 8 – Decent work and economic growth: promote sustained inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all.

- Goal 11 – Sustainable cities and communities: make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable.

The construction of a hydroelectric generating system at Val-Jalbert provides clean energy while having economic benefits to all the organizations involved. In SDG 7, target 7.1 alludes to ensuring universal access to affordable, reliable and modern energy services by 2030 (United Nations, 2015). The new construction of a modern power plant was reliable for its abundant production of electricity: “Production was equal to these facilities: by the late 1950s, it exceeded nine million kilowatts, the highest in Canada, and at 8, 100 kilowatt hours per capita, the highest in the world at the time (Courville, 2008, p.191).” In target 7.2, the efforts to increase substantially the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix are mentioned (United Nations, 2015). The hydroelectric station located on the heritage site of Val-Jalbert has shared the responsibilities between four sponsors: Pekuakamiulnuatsh Takuhikan, the RCM of Maria-Chapdelaine, the RCM of Domaine-du-Roy and municipality of Chambord (Groupe Pek, Val-Jalbert, n.d., para.4).

The Sustainable Development Goal 8, is present for the operation of a tourist destination in the industrial town of Val-Jalbert. In SDG 8, target 8.9 explores the implementation of policies to promote sustainable tourism that creates jobs and promotes local culture and products (United Nations, 2015). This target was clearly achieved within the heritage site; tourism is the contemporary program occurring within the industrial site.

Finally, SDG 11, target 11.4 explains that efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage should be strengthened (United Nations, 2015). The heritage designation of Val-Jalbert considered the built heritage along with the natural heritage of the industrial site as character defining elements where enumerated for both (Canada’s Historic Places, n.d.).

MEASUREMENT

The following table lists the measures describes in an environmental policy developed by the regional county municipality of Domaine-du-Roy in 2015. Although this does not specifically refer to the industrial town of Val-Jalbert, it encompasses the entire RCM of Domaine-du-Roy.

| Policy | Performance | |

| Measure A – maintain an environmental management system and prepare required resources for environmentally responsible activities. | The tourist destination attracts nature admirers to the green forested landscapes. The site offers nature hikes and more activities of the sort that attest to the appreciation for natural environments (Val-Jalbert, n.d.). | |

| Measure B – continuously improve environmental management practices to increase performance. | The Regional Park is continuously adapting to the current technologies. The implementation of electric charging stations encourages visitors to travel with their electric cars, reducing emissions. | |

| Measure C – exercise pollution prevention in environmental and forest management practices. | The industrial town of Val-Jalbert determined a set of rules to be followed by anyone accessing the park. Article 5 a. states that it is forbidden to, “defile park property by leaving behind garbage, paper, liquid or any other refuse other than in garbage cans or other containers provided for this purpose (Val-Jalbert, n.d.)”. | |

| Measure D – minimize negative impacts of the environment by limiting/ reducing emissions, the use of hazardous materials, consumption of energy, and waste. | The example of electric cars can be utilized here, as the vehicles produce less emissions. In addition, the Véloroute des Bleuets might be a wonderful means of green transportation for those, living in the Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean region, who are physically able to bike long distances and willing to accept the challenge (Véloroute des Bleuets, n.d.). | |

| Measure E – provide the information and training required for the application of this policy | This responsibility is essential for consistency across the regional county municipality of Domaine-du-Roy. | |

| Measure F – maintain an open discussion with all interested parties and respect their needs in the decision. | This measure was respected during public consultations held prior to the construction of a power plant (Val-Jalbert, n.d.). | |

| Measure G – constructive collaboration with governing bodies. | Four regional and municipal organizations united to finance the hydroelectric station project; Pekuakamiulnuatsh Takuhikan (45%), RCM Maria-Chapdelaine (22.5%), RCM Domanine-du-Roy (22.5%), municipality of Chambord (10%) (Groupe Pek, Val-Jalbert, n.d., para.4). |

REFERENCE LIST

Books/ Book chapters/ Journal articles

- Courville, S., 1943, & Howard, R., 1940. (2008;2014;2007;). Quebec: A historical geography. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Douet, J., & ProQuest (Firm). (2012;2016;). Industrial heritage re-tooled: The TICCIH guide to industrial heritage conservation. Lancaster [United Kingdom]: Carnegie Publishing Limited. doi:10.4324/9781315426532

- Mieg, H. A. 1., & Oevermann, H. (2015). Industrial heritage sites in transformation: Clash of discourses. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Sæþórsdóttir, A., & Hall, C. (2018). “Floating away: The impact of hydroelectric power stations on tourists’ experience in Iceland.” Sustainability, 10(7), 2315. doi:10.3390/su10072315

- Xie, P.F. (2015). Industrial Heritage Tourism. Retrieved from https://books.google.ca/books?id=hUg9CQAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Lévesque, L. (2015). Val-Jalbert établie la nouvelle norme des mini-centrales. Le Quotidien. Retrieved from https://www.lequotidien.com/archives/val-jalbert-etablit-la-nouvelle-norme-des-mini-centrales-f713d1a0846d743de806fb8a445f58cb

- Shields, A. (2013). Val-Jalbert: Québec a ignoré deux avis du Conseil du Patrimoine. Le Devoir. Retrieved from https://www.ledevoir.com/societe/environnement/369727/val-jalbert-quebec-a-ignore-deux-avis-du-conseil-du-patrimoine

- Tremblay, I. (2012). Manifestation à Val-Jalbert. Le Quotidien. Retrieved from https://www.lequotidien.com/actualites/manifestation-a-val-jalbert-af42c933b042e5365f27a702843478e0

Policies and reports

- Canadian Register of Historic Places. (n.d.). Village historique de Val-Jalbert. Retrieved from https://www.historicplaces.ca/en/rep-reg/place-lieu.aspx?id=5503&pid=0

- Répertoire du Patrimoine Culturel du Québec. (n.d.). Village historique de Val-Jalbert. Retrieved from http://www.patrimoine-culturel.gouv.qc.ca/rpcq/detail.do?methode=consulter&id=92690&type=bien#.XafX63dFxPY

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming Our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Retrieved from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdgs

Websites

- Gagnon, G. (n.d.). Val-Jalbert, la valorisation touristique d’un patrimoine du XXe siecle. Encyclopédie du patrimoine culturel de l’Amérique française. Retrieved from http://www.ameriquefrancaise.org/fr/article-499/Val-Jalbert,__la_valorisation_touristique_d%E2%80%99un_patrimoine_du_XXe_si%C3%A8cle.html#.Xb3R0S0ZNQM

- Val-Jalbert. (n.d.). Activities. Retrieved from https://www.valjalbert.com/en/activities

- Val-Jalbert. (n.d.). Accommodations. Retrieved from https://www.valjalbert.com/en/accommodation

- Val-Jalbert. (n.d.). Services. Retrieved from https://www.valjalbert.com/en/services/charging-terminal

- Val-Jalbert. (n.d.). Mini power plant. Retrieved from https://www.valjalbert.com/en/mini-hydroelectric-power-plant

- Val-Jalbert. (n.d.). Mission and values. Retrieved from https://www.valjalbert.com/en/mission-and-values

- Val-Jalbert. (n.d.). Rules and Politics. Retrieved from https://www.valjalbert.com/en/rules-and-politics

- Val-Jalbert. (n.d.). Village’s Hisotry. Retrieved from https://www.valjalbert.com/en/village-history

- Mairs, J. (2016). Timber-clad walkway wraps Quebec hydroelectric plant by Atelier Pierre Thibault. Dezeen. Retrieved from https://www.dezeen.com/2016/01/04/val-jalbert-belvedere-hydroelectric-plant-atelier-pierre-thibault-ouiatchouan-river-quebec-wood-cladding-walkway/

- Génétique. (n.d.). Val-Jalbert Power Plant. Retrieved from https://www.genitique.com/en/achievements/__trashed/

- Parks Canada. (2019). The Historic Village of Val-Jalbert, Chambord, Quebec. Retrieved from https://www.pc.gc.ca/en/culture/clmhc-hsmbc/res/doc/information-backgrounder/village-val-jalbert

- MRC Domaine-du Roy. (n.d.). Tourisme. Retrieved from https://mrcdomaineduroy.ca/vision-strategique/tourisme

- Moar, C. (2013). Project Val-Jalbert: lettre ouverte du chef Clifford Moar. Pekuakamiulnuatsh Takuhikan. Retrieved from https://www.mashteuiatsh.ca/messages-aux-pekuakamiulnuatsh/actualites/640-projet-val-jalbert-lettre-ouverte-du-chef-clifford-moar.html

- Pekuakamiulnuatsh Takuhikan. (n.d.). Conseil de bande. Retrieved from https://www.mashteuiatsh.ca/bureau-politique-1/conseil-de-bande.html

- Groupe Pek. (n.d.). Val-Jalbert. Retrieved from http://www.pekglobal.com/en/achievements/val-jalbert.html

- Véloroute des Bleuets. (n.d.). Activités et attraits. Retrieved from https://veloroutedesbleuets.com/activites-et-attraits

Feature image: Atelier Pierre Thibault. 2018. View of Ouiatchouan Fall from hydroelectric generating station. [Photograph]. Retrieved from http://www.pthibault.com/project/belvedere-de-val-jalbert/