Case Study prepared by Imogen Goldie, Carleton University

Benny Farm Redevelopment – Maintaining Community While Greening Affordable Housing

Keywords: Affordable housing, community gardens, energy saving, green urbanism, materials reuse, Montreal.

LESSONS LEARNED: The Benny Farm housing project is a complex story spanning almost 70 years. Programmatically it has changed only slightly; established as social housing for veterans, the nature of those serviced expanded to include single-parent and low-income families, seniors and physically disabled individuals. In 2004, it became the location of a large, award‑winning, green urbanism project. This case study focuses on that large-scale redevelopment from uncertain conversations in 1998 to construction between 2004 and 2007. As architect Daniel Pearl (2015) refers to Benny Farm as “the world’s first government‑subsidized, large-scale, community-driven neighborhood renewal project combining affordability, green building technologies, rehabilitation, and new construction,” (p. 13) this case study focuses on two key themes: environmental sustainability and social sustainability. In reusing some of the extant buildings, Benny Farm stands as a strong example of the effectiveness of adaptive reuse and material reclamation in mitigating the waste generated through development. It is also important to note that Benny farm illustrates the impact integrated renewable energy systems can make on the economic viability and sustainability of a project.

As important as the environmental considerations are, maintaining a strong community has played a key role in the ongoing survival of Benny Farm. Community groups like Heart and Hands have been operating in the community since the 1970s and its members were instrumental in developing the contemporary coop programs, like Coopérative d’Habitation Benny Farm/Benny Farm non-profit housing cooperative, Coopérative d’Habitation ZOO (Zone of Opportunity)/ZOO Non-Profit Housing Cooperative and Chez Soi, that operate on the site today. These community groups and others from surrounding neighborhoods were directly involved in planning the redevelopment. This illustrates the effectiveness of community activism and initiatives but also illuminates the features that residents see as increasing the livability and sustainability of their communities, including community gardens and low-speed, heavily treed streetscapes. Finally, a community or resident perspective helps offer a more robust assessment of the effectiveness of a project surrounded with sensationalized and overly positive media attention and discourse. The community viewpoint helps shows that award‑winning planning does not always translate to award‑winning execution.

Presentation. Presentation in class November 21, 2017.

DESCRIPTION: Benny Farm is a 7.3-hectare (18 acre) housing property in Montreal’s west-end Côte-des-Neiges/Notre-Dame-de-Grâce (Notre-Dame-de-Grâce (NDG) before 2002) municipality. Designed by architect Harold James Doran, it was developed beginning in 1944 and constructed in 1946 to house veterans returning from World War II. Originally on the outskirts of Montreal, as the city grew, the site found itself on a much more desirable and valuable piece of land (Baker, 1998, p. 28). This made the development of the property highly contentious and often political.

Through the 1990s while under the ownership of the Canada Mortgage and Housing Company (CMHC), at least three redevelopment proposals were undertaken, with scopes ranging from a complete demolition of all buildings on site in 1992, to a plan that proposed the complete conservation of all existing buildings introduced by the architectural firm L’OEUF in 1994. Finally, in 1998, while still under CMHC ownership, permission was granted to demolish the entire site (Baker, 1998, p. 28). This permission and date also marks the beginning of this case study’s focus. In 1998, in response to the demolition approval architect and community activist Joseph Baker wrote,

“Scandal is not too strong a word for the unjustifiable and imminent destruction of a valuable public resource. To date the Federal Minister responsible for the CMHC has turned a deaf ear to all representation, while the Quebec government has lent a sympathetic one but is powerless to intervene in a jurisdiction not yet its own” (Baker, p. 29)

Ownership changed hands the following year with the site being purchased by the Canada Lands Company (CLC). Discussions were undertaken between the CLC and local organizations as the Benny Farm Round Table with a community group, the Fond Foncier Communautaire Benny Farm (FFCBF)/Community Land Trust Benny Farm emerging from these meetings. After a questionable (Baker, 2003, p.1), failed deal (van Drimmelen, 2007, p. 6) with the newly formed Land Trust, CLC undertook a site redevelopment plan with themselves as the principal developer (Baker, 2003, p 1). In 2002 after more than a decade of citizen advocacy and in service of a more participatory design process, CLC formed a task force of representatives from variety of stakeholder groups (Yilmaz, 2008, p. 1370). After a design competition was held, a plan was chosen that retained 40% of the original buildings along Cavendish Blvd. and created 60% new construction.

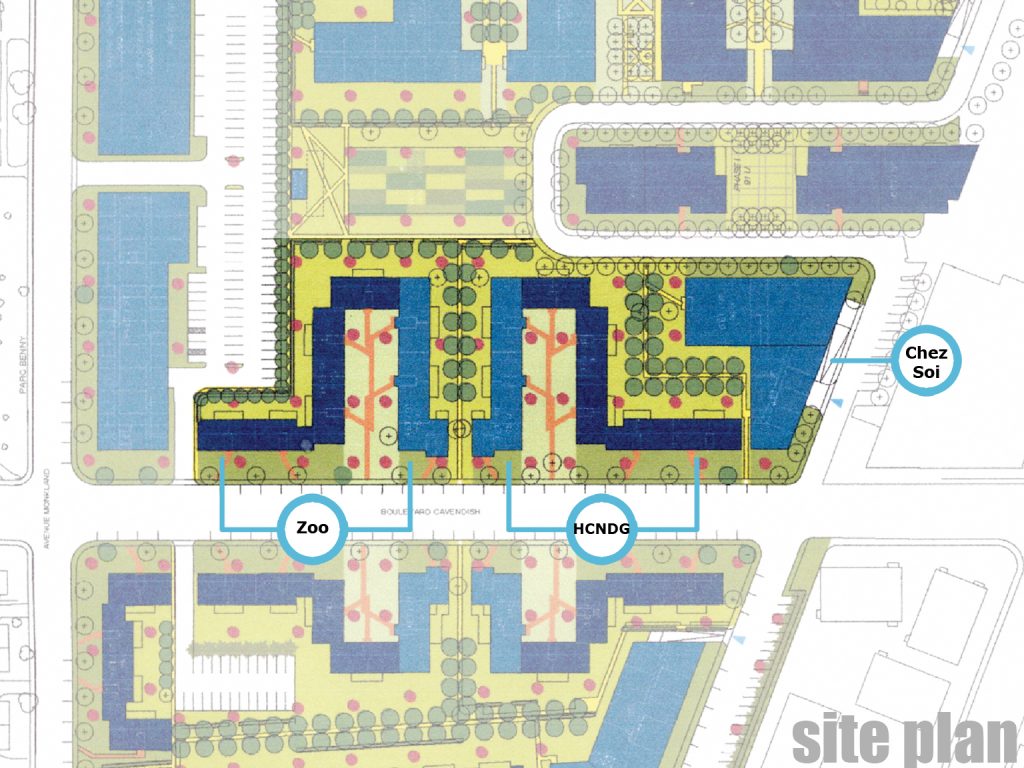

Beginning in 2004, this project relied on a combination of multiple construction approaches and the installation of innovative green systems to provide dense, affordable but ultimately safe and comfortable rental units for at least three co-operative organizations. These three organizations and their corresponding three buildings occupy the east side of Cavendish Blvd. as can be seen in the illustration below.

Benny Farm Redevelopment – www.lafargeholcim-foundation.org

TIMELINE

Selected events. See attachment for detailed list of dates.

TIMELINE Benny Farm – detailed

Site History

- 1944 – property purchased by Minister of Pensions and National Health; first sketches appear in ‘The Monitor’

- 1946 – Canadian Housing and Mortgage Corporation created, purchases the property

- 1947 – Benny Farm built for $3 million, designed by architect Harold J. Doran; 4000 applications by April, first tenants moved in by May

- 1954 – Benny Farm Charter published

- 1970 – Head and Hands Support Group founded

Early Development

- 1983 – government attempts to sell units to the inhabitants

- 1990/91 – CMHC discloses plan to raze site, relocate tenants

- 1991 – CMHC proposal by Gauthier Guité Daoust Architectes (100% new construction)

- 1992 – Montreal’s ‘Master Plan’ released

- 1992 – L’OEUF founded by Mark Poddubiuk and Daniel Pearl

- 1994 – land rezoned, six-storey buildings permitted on site; “counter project” proposed by L’OEUF (100% Conservation); not adopted but strongly influenced redevelopment plan ultimately realized on site; Gauthier Guité Daoust Architectes New Proposal (36% Conservation)

- 1995-1997 – demolition begins according to Gauthier Guité Daoust Architectes plan; first GDA building constructed; 2 six-storey apartments built, approx.90 residents of the old buildings relocated

- 1997 – CMHC pushes to relocate residents, demolish 1940s structures

Redevelopment Plan

- 1998 – CMHC given permission to demolish the site.

- 1998 – CMHC Proposal by Saia Barbarese Architectes (SBA) (100% new construction); 2 new buildings from the SBA plan are built

- 1998 – CMHC sells property to Canada Lands Company (CLC)

- 1998 – Community Land Trust Benny Farm (CLTBF) founded, with an objective to purchase the remaining property on the site.

- 1998 – CLC refuses to sell to CLTBF

- 1999 – round table organized by CLC prior to hosting design competition.

- 2000 – Zone of Opportunity (ZOO) Co-op founded

- 2001 – Fond Foncier Communautaire Benny Farm/Benny Farm Community Land Trust (FFCBF) in conjunction with L’OEUF, sign “protocol agreement” with CLC for 6 months to acquire site – L’OEUF Proposal (100% Consevation)

- 2002 – task force put in place to draw up the plan

- 2002 – CLC Design Alternative (proposals by L’OEUF, Daoust Lestage, Atelier BRAQ, Saia Barbarèse)

- 2003 – development plan presented to the Task Force / Borough of CDN/NDG residents. Final version validated September 10, 2003.

- 2004 – Green Municipality Fund (GMF) application begins for a sustainable infrastructure project, approved by March

- 2005 – Green Energy plan implemented, GMF contract signed. Construction begins.

- 2006 – community- run utility company Green Energy Benny Farm begins operation

- 2007 – properties including those associated with Chez Soi, ZOO and Habitations Communautaires NDG sold to Office municipal d’habitation de Montréal

Awards

- 2002 – Governor General’s Medal in Architecture (Saia and Barbarese and Laverdière + Giguère)

- 2005 – Urban Development Institute of Quebec Award of Excellence

- 2005 – Real Property Institute of Canada Award for Comprehensive Planning

- 2005 – Gold regional Holcim Award “Greening the Infrastructure at Benny Farm”

- 2006 – Bronze Holcim Global Award

STAKEHOLDERS

Selected stakeholders. See attachment for detailed lists.

STAKEHOLDERS Benny Farm – detailed

Community

- Benny Farm Tenants Association Incorporated – Benny Farm Residents

- Coopérative d’Habitation Benny Farm

- Coopérative d’Habitation ZOO (Zone of Opportunity)

- Fond Foncier Communautaure Benny Farm

- Green Energy Benny Farm

Redevelopment Task Force

- Metu Belatchew; Rosemary Bradley; Ken Briscoe; Miriam Green; Needet Kendir; Zane Korytkyo; Ghilaine Prata

Government/Non-Profits

- Canada Lands Company

- Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation

- Chez Soi

- City of Montreal/Ville de Montreal Administration

- Federation of Canadian Municipalities (Green Municipal Fund)

Design

- Claude Cormier and Associés – landscape architecture

- Gauthier Guité Daoust Architectes

- L’OEUF – architectural firm

- Martin Roy et Associes – engineering firm

- Saia Barbarèse (Topouzanov) Architectes

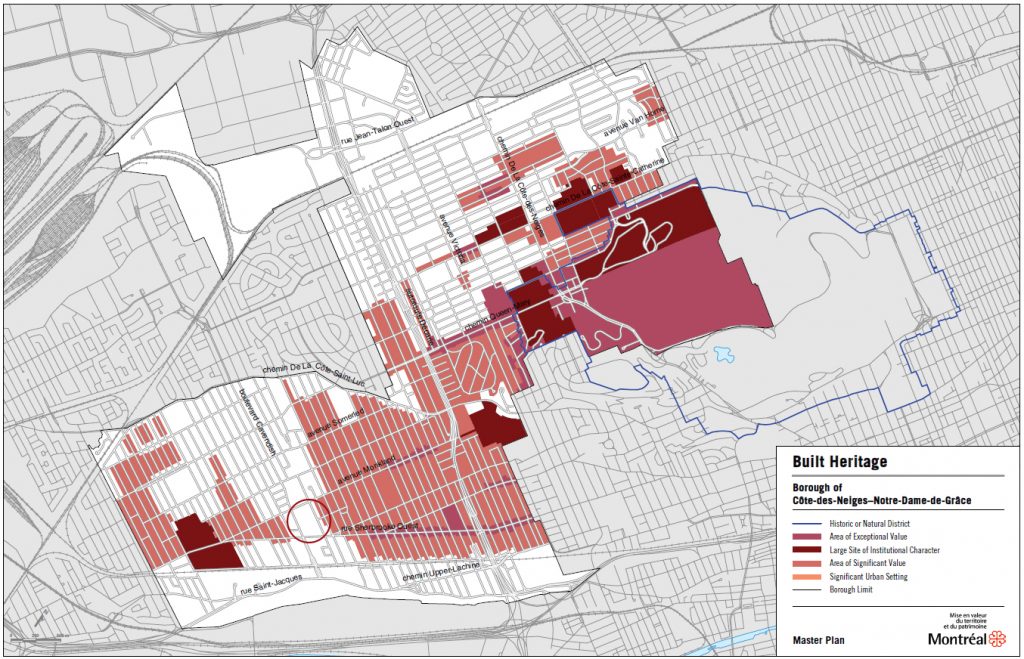

CULTURAL HERITAGE: Benny Farm had in the past been characterized as having little or no historical or heritage value (Fish, 1994, p.2; Baker, 1998, p.29). In 1992, coinciding with the early CMHC attempt to demolish the site, Montreal’s “Master Plan” was released. The plan (see below) highlighted neighborhoods and areas that held varying levels of heritage value. Benny Farm was left entirely blank (Fish, 1994, p. 2).

Near the end of the 1990s when CMHC was once again pushing to demolish, their heritage consultant wrote, “the Benny Farm buildings are not of sufficient historical, architectural, urbanistic or environmental interest to justify conservation as a heritage property” (Baker, 1998, p. 29). This opinion of an absence of heritage value arose again with Montreal’s 2002 “Master Plan,” and once again, though bordered to the east and west by areas of “exceptional value,” Benny Farm remained entirely blank (Benny Farm site circled for the purpose of this case study).

Montreal Master-plan 2002, Areas of Built Heritage Value – http://ville.montreal.qc.ca

Benny Farm’s first families – coolopolis.blogspot.ca

Architects like Joseph Baker have contradicted this absence of heritage value, citing Benny Farm as being an “expression of our society,” also noting that “perhaps it would serve to remember, with more than poppies on our lapels each November, how we faced up to our responsibilities to those who served” (Baker, 1998, p. 29.) Baker identifies the connection between Benny Farm’s original social housing purpose and Canada’s involvement in WWII as the “cultural context of our built stock,” following an idea proposed by historian and planner Jean-Claude Marsan (Baker, 1998, p. 29).

Benny Farm under construction, 2947 – BANQ/Fonds Conrad Poirier

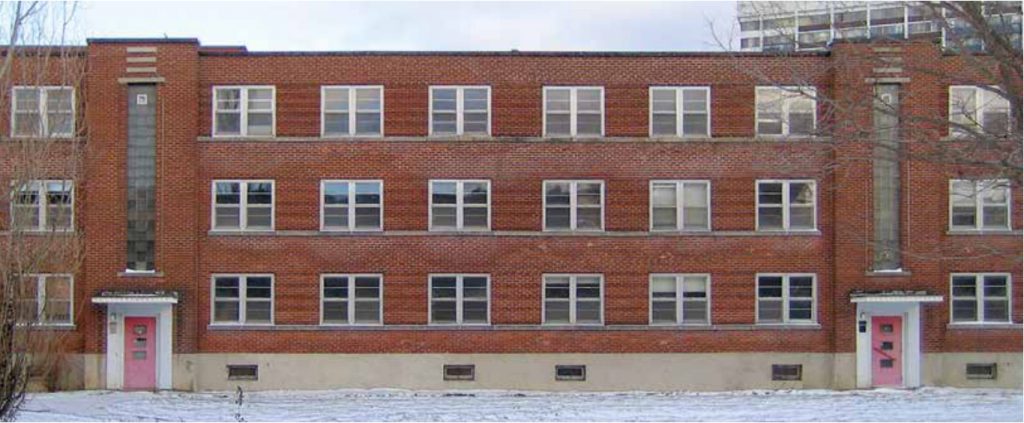

Benny Farm’s built environment also has ties to the ‘Amsterdam School’ style of architecture (Baker, 1998, p. 29), which had emerged in the Netherlands in the early twentieth century. This can be seen in the humble, but expertly applied art deco-styled brickwork and the artistic use of glass blocks. Further, its urban planning was inspired by the “Garden City Movement” (Baker, 1998, p. 29) theorized by Ebenezer Howard in his 1898 book To-morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform.

“in this tradition it was a brave vision that offered the returning servicemen, a healthy, spacious environment in which to raise their families (Baker, 2003, p. 2).

Benny Farm 1940s Facade – src.lafargeholcim-foundation.org

Benny Farm’s contribution to Montreal’s exemplary built heritage is embodied in these ties to Canada’s militaristic history and in the well-constructed buildings holding deeper ties to a wider architectural discourse. It is also easy to see how these ideas were maintained in the Benny Farm redevelopment expanded on below.

ENVIRONMENTAL SUSTAINABILITY

“The redevelopment of Benny Farm represents a significant step forward in bringing sustainable energy efficient design to affordable housing in Canada.” (Market Wired, 2006)

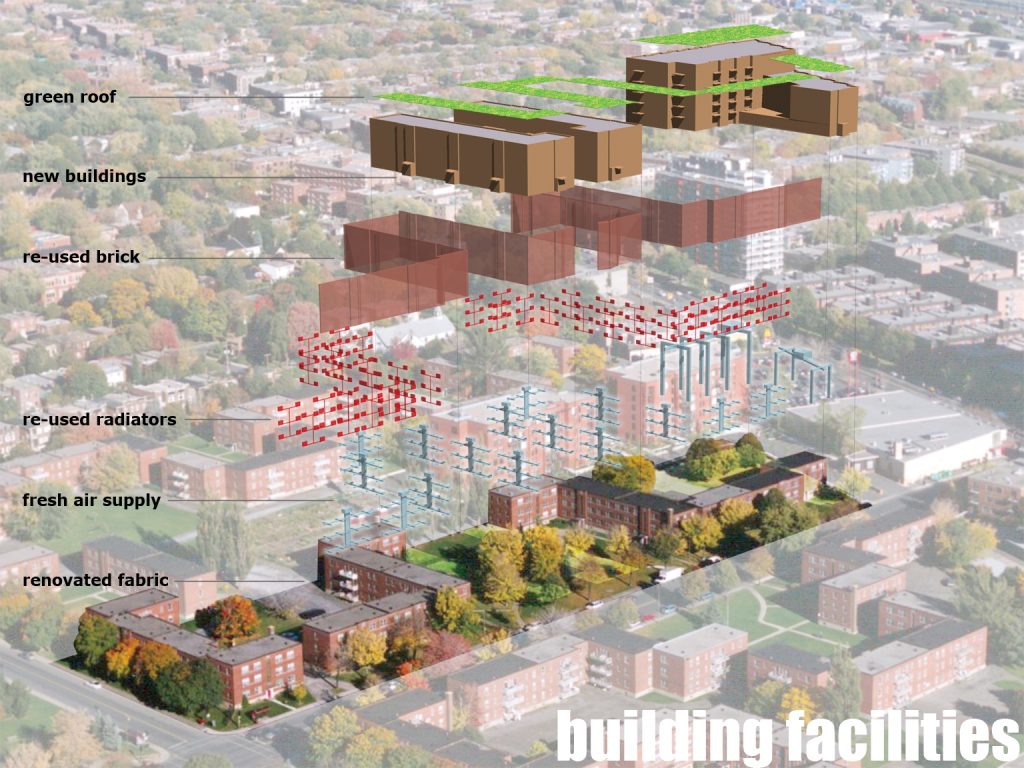

Benny Farm Facilities – lafargeholcim-foundation.org

Sustainable materials: The building strategy behind Benny Farm addressed environmental sustainability concerns in several ways. First, through the materiality. The project involved the reconditioning and reuse of some of the original 1940s building stock, the project capitalized on the high-quality materials used in the original project including the plank hardwood floors, thick spruce sub-flooring, pine doors and cabinets and interior double layer gypsum board partitions (Baker). The amount of waste generated by the partial demolition and subsequent renovation of several of the buildings on site was also mitigated by the reclamation and reuse of materials.

- During work on the building envelopes, dismantled brickwork was sorted by condition and potential usefulness, later utilized in the new building construction as well as in the repair of any degraded early facades that were being retained (Lafarge Holcim, 2006, p. 2).

- The original cast-iron radiators were saved as it was discovered that they would be compatible with the planned geothermal heating system (Lafarge Holcim, 2006, p. 2).

- Glass blocks that were originally used to allow light into the building’s central stair-wells were used as partitions between individual unit’s entry foyers (CMHC, 2006, p. 1).

- New materials included the use of fibreglass framed, double-glazed, low-e, argon-filled, insulated glass units (innovative building) and the utilization of insulated steel doors for the entries (CHMC, 2006, p.1).

- Many other construction materials were chosen for their recycled content (Lafarge Holcim, 2006, p. 2).

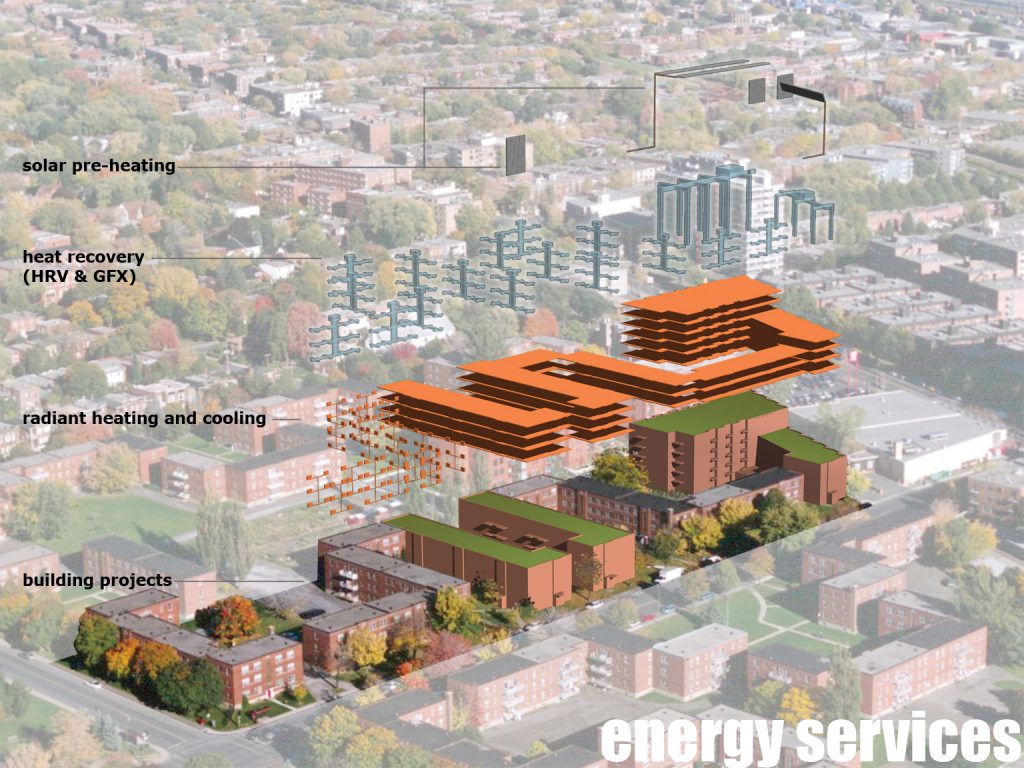

Energy Systems – lafargeholcim-foundation.org

Renewable Energy: Starting at their core, the renovated buildings were to receive structural upgrades to accommodate the proposed new loads of a green roof, but also to future proof for later adjustment and expansion. This involved stripping roofs down to their rafters and installing rigid insulation and an air barrier to improve the building’s overall thermal performance. The process of conversion to a green roof was scrapped due to both technological and financial limitations (CMHC, 2006, p.2).

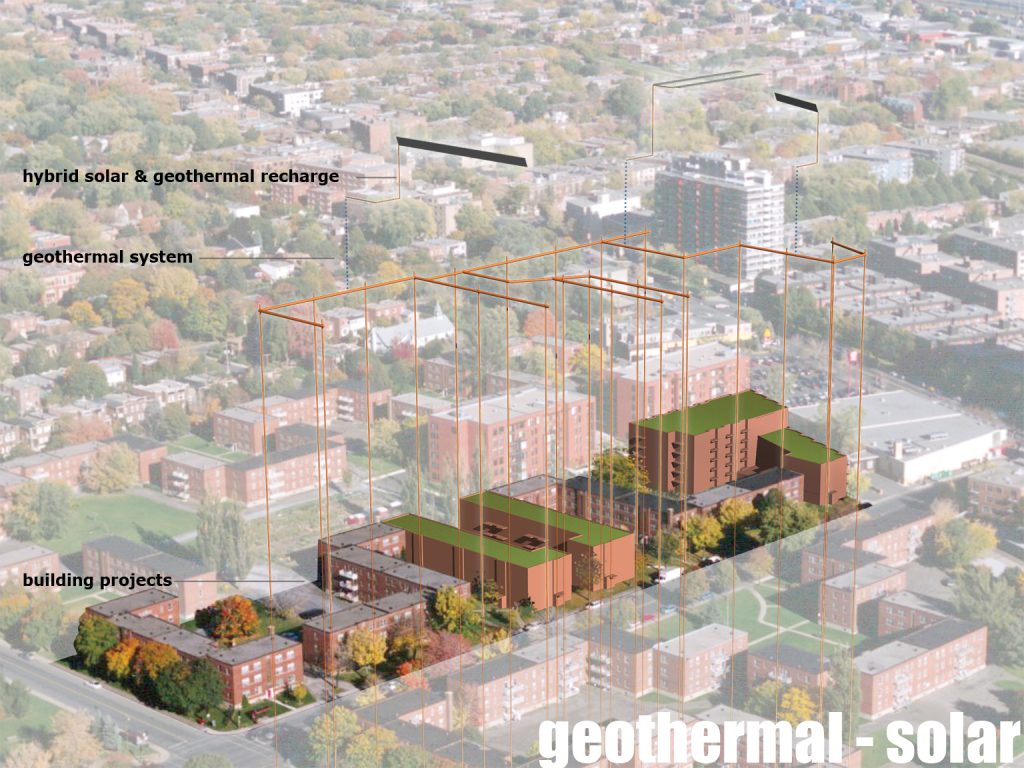

Geothermal and Solar Systems – lafargeholcim-foundation.org

Benny farm utilizes both geothermal and solar energy in its heating system. This includes roof mounted evacuated tube solar panels and a solar wall; it also involves geothermal wells bored on the property to a depth of about 200m (Lafarge Holcim, 2006, p. 4; Pearl, p. 43). This energy is then transported through all three buildings through an integrated community energy system. To run the operation, a non-profit, community-run utility company called Green Energy Benny farm was developed (Pearl, p. 41).

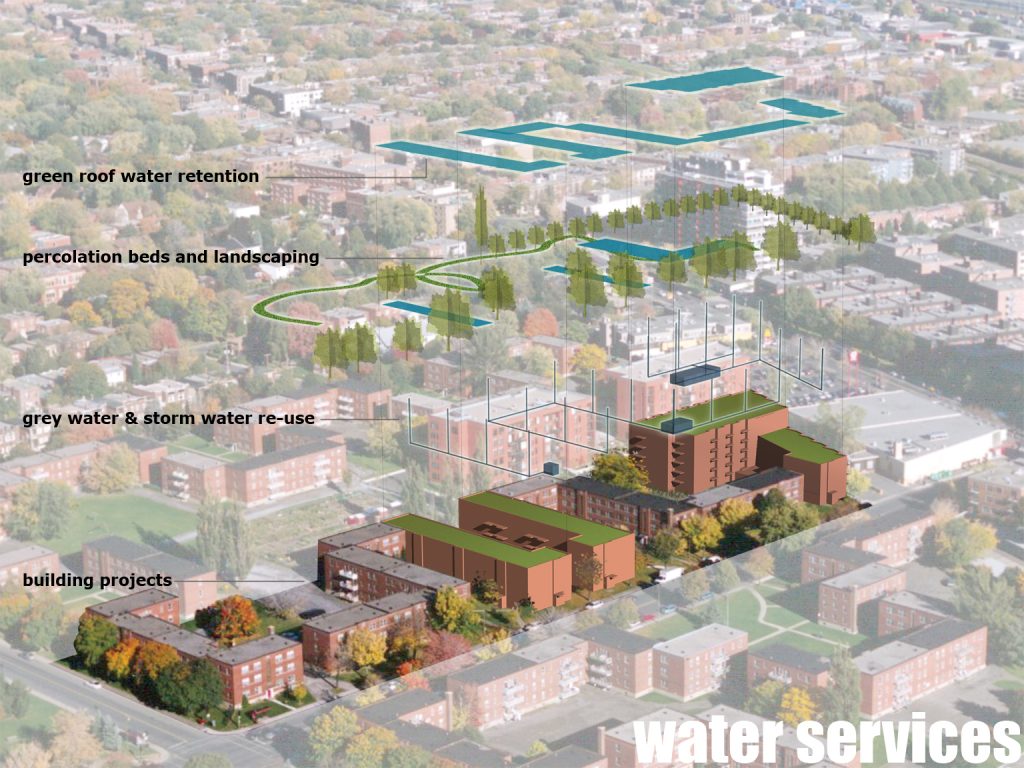

Water Systems – lafargeholcim-foundation.org

Finally, water is also considered a finite resource in the redevelopment. Aside from all fixtures being replaced with efficient, low-flow heads and taps (innovative building), and toilets, with low-flow units (CMHC, 2006, p. 1), sustainable water systems were installed, including: a storm water retention system, and percolation beds for the extensive gardens and grey water retention (Lafarge Holcim, 2006, p. 4; Pearl, p. 43).

SOCIAL SUSTAINABILITY

Benny Farm Community Garden – lafargeholcim-foundation.org

A key factor in Benny Farm’s social sustainability is in its continued support of social housing. Over 200 of the units in the redevelopment are operated co-operatives and other non-profits that target groups who are most vulnerable in relation to shelter and other services. (CLC, 2003, p. 9)

Benny Farm and residents of the larger NDG neighbourhood have a long history with the ‘green landscape’ and the act of community gardening. Many of the young mothers living in Benny Farm in the 1990s were participating in the community-run Friendship Garden behind NDG’s Wesley United Church (Moatasim, 2005, p. 76-77). Community gardens foster a sense of community and facilitate friendships (Moatasim, p. 77). Hence, a community garden became an integral feature of Benny Farm’s redevelopment and landscape design. The gardens and green-spaces were created by landscape architecture firm Claude Cormier and Associates and retained many of the original Garden City ideals, by creating large, lush, green common areas and many tree and bench-lined, walkways. Within the general objectives of the CLC redevelopment plan, several elements were developed entirely in service of livability and social sustainability. Housing distribution was planned in a way that located seniors and veterans homes together to promote a quite zone and sharing of services (CLC, 2003, p. 8). Conditions put in place to respect the neighbourhood included height limits on the buildings that faced the smaller residential lots on the streets surrounding Benny Farm.

MEASUREMENT: The Lafarge Holcim Foundation was created in 2003 to contribute to and help facilitate sustainable construction practices. They do so through publications, but most notably through their regional and international sustainable construction competitions. In 2005, the “Greening the Infrastructure at Benny Farm” project won Gold at Holcim’s regional level, later taking Bronze in the global competition. The criteria Lafarge Holcim uses to assess competition entrants thus offers a framework for measuring the effectiveness of Benny Farm’s sustainability efforts. The selection criteria are broken down into five pairs, with many sections interrelating or overlapping: “Innovation and Transferability”, “Ethical Standards and Social Inclusion”, “Resource and Environmental”, “Economic Viability and Compatibility” and finally, “Contextual and Aesthetic Impact”. Lafarge Holcim also refers to these five sections as 5 ‘p’s: progress, people, planet, prosperity and place.

- Innovation and Transferability – Progress: To fulfil this criterion, there must be evidence of not only sustainable development, but innovation and exploratory work in service of said sustainable development. There is also an aspect of flexibility, as “breakthroughs and trend-setting discoveries must be transferable to a range of other applications.” (Lafarge Holcim)

-

- The Benny Farm project meets the Innovation and Transferability criteria through its material use and reclamation, its renewable and interconnected energy systems, its empathetic landscape design and through the documentation and publication of the project through online and print publications.

-

- Ethical Standards and Social Inclusion – People: Considered projects must adhere it high ethical standards and “promote social inclusion at all stages of construction, […]” There must be evidence that the project has or will impact the community in a positive manner. (Lafarge Holcim) On the matter of Benny Farm, architect Phyllis Lambert wrote, “my first and primary concern is the social approach adopted. Benny Fram, as originally constituted by the CMHC had a social purpose. The rare commodity – social responsiveness, is of the greatest importance to the well being of all Montrealers” (Lambert, 2003).

-

- Ethical standards and social inclusion were neglected in the original Benny Farm plans, but embraced a little more emphatically in the Benny Farm redevelopment project. This was achieved at conception and design stages through creation of the advisory task force by CLC in 2002. This task force composed of ten members was meant to represent the various interest groups and perspectives on the project. It featured a range of local community and municipality representatives along side those representing the land owner (CLC, 2003, p. 25). After the contentious plans of the 1990s under the CMHC, CLC wanted to ensure the new plan contributed to an inclusive and integrated community while also retaining as much of the historical as was feasible.

-

- Resource and Environmental Performance – Planet: These criteria appealed to the Green Benny Farm project’s strengths as it’s emphasis was on the “sensible use of material and resources” (Lafarge Holcim)

-

- Benny Farm utilized and rejuvenated portions of the site’s built fabric to reduce the generation of emissions and waste. New products were chosen based on environmental impacts and many older materials were used rather than having all new items manufactured and shipped to site. The award also uses water and land reclamation as an indicator of a project’s effectiveness. The Benny Farm redevelopment put a heavy emphasis on green areas, and developed a simple but effective community water system.

-

- Economic Viability and Compatibility – Prosperity: To achieve this criterion, projects must be, “economically feasible and able to secure financing.” (Lafarge Holcim)

-

- There is less publicly available documentation on the specific means CLC utilized in financing the Benny Farm project, though as a “self-funding, arms-length, ‘non-agent’, federal Crown corporation,” (CLC, 2003, p. 2) whose purpose is to purchase, improve and manage or sell government properties, there were probably related funding resources available to them. The project itself maintained economic viability by driving down construction and waste costs, and seeking to generate their own energy, thus driving down operation costs.

-

- Contextual and Aesthetic Impact – Place: For this criterion, the project is required to have extremely high standards of architectural quality. Space, form and aesthetic impact are weighed heavily, as well as the projects ability to “make a positive and lasting contribution to the physical, human and cultural environment.” (Lafarge Holcim)

-

- The Benny Farm redevelopment project made improvements to the overall context of the project through upgraded landscape design that not only retained past Garden City ideals but improved accessibility for aging and vulnerable residents. This design was combined with the “sensitive restoration” (Lafarge Holcim) of at least some of the existing building stock and through the reuse of those structures that may not have been able to be saved.

-

References

Books/Journal Articles

- Baker, J. (1998). Selling the farm. The Canadian Architect 43(9), 28-29.

- Moatasim, F. (2005). Practice of Community Architecture: A Case Study of Zone of Opportunity Housing Co-Operative, Montreal. Research Report, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec.

- Pearl, D. & Wentz, D. (2014). Community-Inspired Housing in Canada.

- Silver, E. (2008). “Hope, Effort, Family.” The Benny Farm Community Then…and Now? Montreal as Palimpsest: Architecture, Community, Change, Montreal, Quebec, April 18, 2008. (p.1-21).

- Van Drimmelen, A. (2007, Jan/Feb). Greening the Farm. This 40(4), 6.

Policies and Reports

- CLC. (2003). A Project for the Community.

- CMHC. (2006). Redeveloped Benny Farm Brings 60-Year-Old Garden City Back to Life.

- CMHC. (2006). Innovative Buildings: Benny Farm Redevelopment, Montreal.

- CMHC. (2011, October). Case study research on social housing development.

- Fish, M. J. S. (1994). The Benny farm: A brief asking the City of Montreal to cite the Benny Farm housing and its garden courts as a heritage site; also, asking for support for a non-profit group trying to buy the Benny Farm to continue and further develop its mission; also, a plea to conserve the Benny Farm Project from any demolition. Montreal: Goliath Printing.

- Lafarge Holcim Foundation. (2006). Greening the Infrastructure at Benny Farm.

Websites/News articles

- CTV News. (2014, October 18). Broken Elevators Leave NDG Residents with Reduced Mobility Stuck in Apartment. CTV News Montreal.

- Lefarge Holcim Foundation (n.d.-a) Targets.

- L’OEUF. (2007). Project: Benny Farm.

- Market Wired. (2006, April 25). ‘Green Energy Benny Farm’ Project Takes Bronze Prize at Global Holcim Awards. Market Wired.

Other

- Baker, J. (2003, November 26). Benny Farm Redevelopment [Letter].

- Lambert, P. (2003, November 25). Comments by Phyllis Lambert on the Proposed Master Plan for Benny Farm of 26 September 2003 [Letter].

- Yilmaz, M. (2008, May). Sustainable Community Design – Benny Farm/Montreal as a Sample. Presented at the International Design Conference, Dubrovnik, Croatia.

- Chen, D.H., Greenwald, A.G., & Yamaguchi, S. (2003, June). Cross-cultural comparisons of implicit and explicit self-esteem. Poster presented at the 5th annual meeting of the NorthWest Cognition and Memory Conference, Seattle, WA.