From Endangered Industrial Site to Community Landmark: Sustainable Rehabilitation of the Salt Building, Vancouver

Case Study prepared by Shivani Kaul, Carleton University

Keywords: Sustainability, Industrial Heritage and Landscape, Rehabilitation, LEED certification, South East False Creek Neighbourhood, Vancouver

LESSONS LEARNED

Heritage buildings tend to be innately sustainable and there are many good examples of where sustainable practices have been aptly incorporated in their conservation. One such building, which this case study explores for its rehabilitation of holistic sustainable neighbourhood design, is the Salt Building. Located in Vancouver’s Olympic Village neighbourhood, the Salt Building is an example where sustainable practices are integrated with adaptability concepts and heritage rehabilitation. The site maintains a balance between the pillars of sustainability as the project not only fulfils the needs and aspiration of the community being socially sustainable but also represents itself as an excellent example of both economic and environmental sustainability.

Originally constructed in 1930 for refining salt, the building was later abandoned for many years, and severely deteriorated (Heritage Vancouver, 2002). Many times, such a building would have been dismantled and ended up in a landfill to make space for a new building. However in 2009 the Salt Building was restored in an exemplary manner for Winter Olympics Games 2010, demonstrating that a significant amount of energy and resources can be saved by retrofitting and reusing a heritage structure. From this case, however, it can also be understood that making decisions for architectural or other interventions on a heritage structure often faces several site-specific challenges that must be addressed. For the Salt Building, protecting the historicity and materials of the structure while upgrading it for its functional use was one of the major challenges. The historic structure which lies in a high earthquake risk zone was upgraded seismically which represents building resilience.

The rehabilitation of the building incorporated several sustainability strategies which validate that with an appropriate approach, an endangered heritage site can also become a milestone. Presently, the building stands as an active community gathering space and one of the rare examples of the heritage building to receive LEED-CS Gold certification. Thus, it can be learned that the community always remains a major driving force for a successful sustainable heritage conservation project and strong interventions (not always minimum) are at times required for the benefit of the people.

The heritage structure narrates a story of its continuous interaction between man and nature over a period and the importance of salt in the historic industrial neighbourhood describing how the food was preserved using salt. The later usage of the building as a recycling paper industry indicates the awareness about sustainability and people’s initiatives to save resources. The past and the present uses of the Salt Building underline the educational significance of the heritage site.

PRESENTATION

The case study was presented at Carleton University on November 21, 2019. The presentation outlines the key aspects of heritage sustainability for the Salt building, Vancouver and describes how a neglected site was rehabilitated and established as a landmark for the SEFC community.

DESCRIPTION

The Salt Building is in Vancouver’s South East False Creek (SEFC) neighbourhood also known as Olympics Village. It was constructed in the year 1930 as a refinery for the salt, which was shipped from San-Francisco (Vancouver Heritage Foundation, n.d.). The Salt industry that was mainly used by the local fish and food industry of the False Creek, gradually declined after the change of transportation from the shipping to railways. In 1987, the building use was changed to a Paper recycling plant under Belkin Paper Stock Ltd. (Green Building Brain, n.d.).

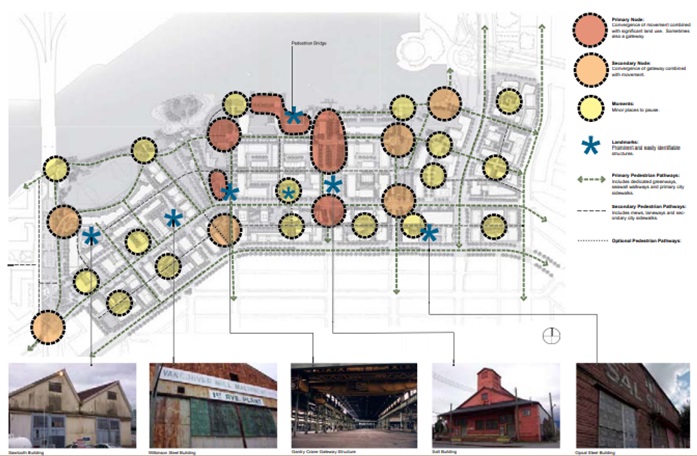

Afterwards, the building was severely deteriorated, abandoned for many years and was among the Vancouver Heritage Society’s Top Ten Endangered Sites in 2002 (Heritage Vancouver, 2002). In 2006, the city of Vancouver prepared South East False Creek Public realm proposal in which 5 heritage buildings with historic value were identified to be maintained and the Salt building was one of them. The building was part of the historical shipyard neighborhood and the only surviving industrial building of that time in the neighbourhood. A consortium was designated to renovate and rehabilitate the building as a community lounge and an interactive place for the athletes for the Winter Olympics Games-2010. In 2009, the rehabilitation project of this 1509 sqm building was completed in 20 months. The building received a LEED-CS gold certification in 2012.

To meet the LEED certification requirements and restore the building to the modern standards, various sustainable construction methodologies like raising the existing timber foundation with steel piles to match the street level; repairing of the original timber trusses; protecting and reusing original material, procuring other materials locally and regionally, etc. were incorporated. In order to meet heritage concerns especially preserving the historic clapboard exterior cladding, the structure’s wall insulation and rainscreen were installed from the interior (Sorensen, 2010.).

Vancouver is earthquake-prone and hence many historic buildings are dismantled to ensure the safety standards. However, for the rehabilitation of the Salt building, this historic structure was seismically upgraded (Sorensen, 2010) which reflects its characteristic being seismic resilient.

The use of the building was changed in the year 2013 and today it operates as a SEFC community craft beer pub, bakery and a coffee house (Wilson, 2013).

TIMELINE

| Pre-settlement | Part of the natural history | |

| Settlement | The land and the water belonged to the Coast Salish people | |

| 1913 | The shoreline changed and only then there was a space for utilizing the land | |

| After 1913-1930 | The site used was used a gravel storage | |

| 1930 | The Salt Building was originally constructed as a salt refinery, The Vancouver Salt company | |

| 1950 | As False Creek’s industrial base grew, the waterfront access was filled | |

| 1954 | The demand for salt was high and therefore to accommodate new equipment Northern side of the building was expanded | |

| 1970 | The building was taken over by the Arden Vancouver Salt Co. Ltd. | |

| 1987 | The Salt Industry declined after the change of transportation from shipping to railways and the building was used as a Paper recycling plant under Belkin Paper Stock Ltd. | |

| 2006 | It was abandoned for several years and only in 2006, the city of Vancouver identified the Salt building as heritage and included it in the SEFC public realm proposal | |

| 2007 | The city of Vancouver appointed a consortium to renovate and re-use the building as a lounge and gathering place for the athletes during the Olympics Winter Games | |

| 2008 | Registration for the LEED CS certification | |

| 2009 | The rehabilitation project was completed in November 2010 for the Winter Olympics | |

| 2010 | The Salt Building received many awards including the Heritage BC Award of Honour, Canadian Institute of Planners Award, Canadian Association of Heritage Professionals Award, and Vancouver Regional Construction Association Award | |

| 2011 | The building received the City of Vancouver Heritage Honour Award and Canadian Wood Council Green Building Award | |

| 2012 | The Salt building received LEED-CS Gold certification | |

| 2013 | The heritage building was adapted again for use as a community brewpub, bakery and coffee house | |

| 2014 | The Salt Building was awarded a Heritage Canada-National Trust Award |

STAKEHOLDERS

Organizations: The concerned organizations for the rehabilitation project of the Salt Building include:

- Canada Green Building Council,

- Vancouver Heritage Foundation,

- Heritage Canada, Heritage BC,

- Canadian Wood Council,

- Canadian Institute of Planners,

- Canadian Association of Heritage Professionals, and

- Vancouver Regional Construction Association.

Owners/users: The City of Vancouver is an unceded territory of Coast Salish People.

- The Salt building is a designated Heritage B structure and comes under the jurisdiction of the City of Vancouver who is the owners of the land.

- Presently, the site is managed by the Marks James Group who is running the brewpub and coffeehouse.

- The various users of the brewpub and coffee house consist of the South East False Creek community, Vancouverites and other guests.

Consultants: The rehabilitation project involved various consultants to restore the deteriorated structure and fulfill the LEED certification requirements.

- In most of the rehabilitation projects the sustainability consultants are not involved whereas in this case, Recollective, a sustainability consultant was included in the team especially for the certification.

- The other consultants comprise Commonwealth Resource Management Ltd as a heritage consultant,

- Acton Ostry as project architects,

- Haebler Construction as Contractors,

- Cobalt Engineering for Mechanical Engineering,

- Glotman Simpson Consulting Engineers for Structural Engineering,

- Gage-Babcock & Associates ltd for Safety,

- Morrison Hershfield for other engineers and managers and

- Citysphere Project Management was responsible for the overall management of the rehabilitation project.

HERITAGE

The Salt building is a designated Heritage Category ‘B’ structure and falls under the jurisdiction of the City of Vancouver (City of Vancouver, n.d.) for representing the historical style of early 1900’s industrial architecture and having cultural significances in the False Creek neighbourhood.

Natural heritage: The Salt building site represents an evolved and continuing cultural landscape of the SEFC neighbourhood. It is an Industrial Cultural Landscape site which is the only surviving structure of the strong industrial history from Shipping Yard of the False Creek, that earlier included several other industries.

The SEFC has a diverse history related to its origin, use of the land and a continuous association of human interaction with nature. Its value resides in its pre-settlement natural history, Coast Salish people’s history and post-settlement history as an industrial area. “Industrial uses were shaped by both private and public landowners from the late nineteenth century until the end of the twentieth century. Most of the land in SEFC was created by filling the estuarine wetland throughout the twentieth century” (SEFC Public Realm Proposal, City of Vancouver, 2006).

The changes to the landscape and the relationship of the water made possible for the building to even exist. The present site was part of the natural waterbody before the shoreline changed. The changing shoreline during 1913 enabled the construction of the industrial park in the neighbourhood. The building was constructed in 1930 above the historic shoreline and wooden timber piles were used for its construction. These historic timber piles are visible today.

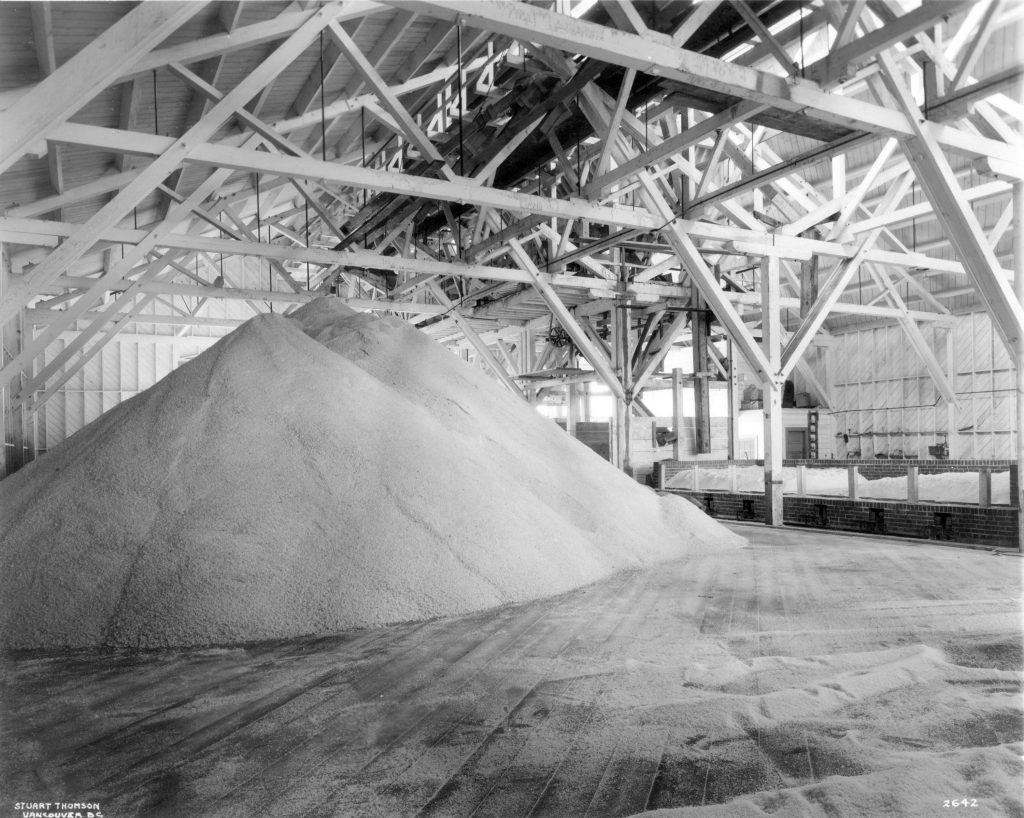

The building used as a Salt processing unit represents the relationship between False Creek and other food-fishery industries for preservation. “Unrefined salt was shipped to Vancouver from the San Francisco Bay Area where it had been recovered from brine by solar evaporation. This was an unusual technique that was traditional to the Bay area. It had originated with the Ohlone Indians and was continued by the Spanish missionaries. The Vancouver bound salt was extracted by the Leslie Salt Refining Co. of Newark, California (bought in 1978 by Cargill Inc.) which owned the Vancouver Salt Co. The operation changed to Arden Vancouver Salt Co. Ltd. in 1970 and was later acquired by Domtar Ltd. Raw salt was unloaded at Burrard Inlet and brought by scow to False Creek where the Vancouver Salt Co. ‘semi-refined’ it by washing, drying, grinding, and sifting it into a coarse product fit for human consumption. The original market was as a preservative for the fishery, particularly the area’s Asian-Canadian fish packers. Later uses included other kinds of food-packing, tanneries, cold-storage plants and highway ice removal” (Vancouver Voyager, n.d.).

By 1950, shipping replaced railways reflecting the changes by the transportation system and the salt trade declined. In the year, 1987, the replacement of the salt-processing equipment with paper shredding machinery reflects the growing importance of the recycling industry and people’s initiatives to save resources.

Therefore, the site and the structure have a great significance as a reminder of the rich Vancouver industrial past. The site has a constant connection to the natural waterbody, i.e. the False Creek over the years that forms a part of the historic shipyard SEFC neighbourhood. The building is a landmark in the neighbourhood that has maintained a continuous relationship with the site which provides a picturesque silhouette and highlights the setting of the structure with its industrial identity.

Cultural heritage: The Salt building is an excellent example of an industrial typology of the early twentieth-century architecture that reflects the industrial features which were common during that period. The building is the only standing structure of the historical shipyard neighbourhood of the South East False Creek. It always was a significant site as a salt refinery for the neighbourhood especially for the fishing and food industry who relied largely on the salt for the process of preservation.

Constructed in the 1930s, the Salt building is a remnant of Industrial Architecture with heavy timber structure and clapboard siding as a building material. It is a single storey building and has a complex system of wooden trusses supported by wooden piles to create a large space. It has a gable roof on the top with a clerestory to provide natural light and ventilation.

The heritage site also represents the identity of the Olympics athletes, the SEFC community associating with the building and industrial ancestry. The building signifies its authenticity and integrity in its existence, historical components, and continuity with time. It is a landmark building of the community that reflects a strong emotional and symbolic value attached to it. The site today continues to be habitable and is used as a community brewpub and a gathering space. It has an economic significance related to its function and for supporting employment in the SEFC neighbourhood.

SUSTAINABILITY

The site maintains a balance between the sustainability pillars as the project not only fulfil the aspirations of the neighbourhood being socially sustainable but also represents itself as an excellent example of both economic and environmental sustainability.

Environmental: The location of the building provides good access to pedestrians and public transportation. The pioneering qualities of the building range from macro-scale of a sustainable neighbourhood design to the micro-scale related to the design details of the structure such as “NEU that reclaims heat from sewage wastewater to service to the building’s highly efficient radiant floor heating system” (Green Building Brain, n.d.).

The project received LEED Core and Shell Gold-level certification, by complying with different factors including natural lighting and ventilation, durability, high ceilings, maintenance, retrofitting of wooden trusses, etc. See more below under Measurement.

The conservation approach includes reuse of more than 75 percent of the existing material to provide durability and create a cavity wall system for the rainscreen and thermal performance upgradation (Green Building Brain, n.d.) while respecting the spirit of the place. Other building materials required for the project were sourced locally and regionally which affects the overall embodied energy, approximately 98 percent was construction waste from landfills and 15 percent of recycled material was used for rehabilitation (Green Building Brain, n.d.). With the NEU system up-gradation that serves the entire SEFC area, the Salt building is estimated to save around 1400 gigajoules of energy and reduces a significant amount of approximately 150 tons of carbon dioxide (embodied carbon) every year (Green Building Brain, n.d.). The industrial site that was on the verge of dying got contaminated over the years, for the rehabilitation, the contaminants such as asbestos, lead, fecal material from birds, etc were identified and removed (Sorensen, 2010). The existing windows on the east and west which allowed for natural light to enter the building were retained and repaired while new glazed windows were added to the north and south walls to enhance daylighting and natural ventilation (Green Building Brain, n.d.).

Fig.6: Salt Building raised with steel pile extensions, Source: Acton Ostry. (n.d.). Salt Building. Retrieved from https://buildingresilience.ca/case-study/salt-building/#iLightbox[gallery_image_1]/2

Fig.7: Existing timber trusses were repaired installing steel plates at connection points, Source: Acton Ostry. (n.d.). Salt Building.Retrieved from https://www.actonostry.ca/project/salt-building-vancouver/

Social/ Cultural: The rehabilitation of the Salt building is environmentally sustainable. It is an example of maintaining community health and resilience through adaptive design. The neighborhood’s liveliness and wellbeing are enhanced when they share experiences and resources. The heritage building stands as a landmark in the neighbourhood and increases interaction between locals being an active community gathering space. Moreover, it provides an employment opportunity for the local SEFC community at the same time. The building also educates the people about the unique industrial heritage of the neighbourhood and sustainable features incorporated in it.

Economical: The Salt building is an economy generating site used for retail food services such as brewpub, coffee shop and bakery, which makes it self-sustainable. The building saves a considerate amount of approximately $19,000 per year being energy efficient (Green Building Brain, n.d.). For the project, to support the local economics, local and regional materials were sourced and used for the rehabilitation.

Sustainable Development Goals: The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 2030 (SDGs) specifically Target 7.3, 8.5 and 11.4 are associated with the rehabilitation project of the Salt Building. Target 7.3, that is ‘double the global rate of improvement in energy efficiency’ is evident in this case as the building was upgraded to the Neighbourhood Energy Unit (NEU) system that reclaims heat from sewage wastewater to service the radiant floor heating of the building (Green Building Brain, n.d.).

Target 8.5 that mentions, ‘achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men, including for young people and persons with disabilities, and equal pay for work of equal value’ corresponds to this as the present use of the heritage building as a brewpub and coffee house, provides job prospects and economic opportunities to the people of the SEFC neighbourhood.

The overall protection and rehabilitation of the heritage site align with Target 11.4 that is, ‘Strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage’.

MEASUREMENT

The Salt building is an outstanding example of environmental sustainability that is demonstrated by the inclusion of sustainable building practices while preserving its heritage values. The project has won many accolades and awards after its completion. It is one of the only few heritage projects in Canada to achieve LEED-CS Gold certification. The LEED scorecard is used to assess the environmental sustainability of the building. The scorecard in totality presents a good representation of sustainable works on the existing heritage building.

The LEED Scorecard for the Salt Building is retrieved from:

LEED Project Information (CaGBC, 2019)

- Rating System-LEED Canada Gold for Core and Shell Development-1.0 : 40 points achieved out of 70 possible points. Gold Assessed as 39-51 points

- Project Size: 1509 m²

- Project Type: Retail

- Owner Type: Government-Local

- Certification Date: 2012-03-08

| LEED CATEGORY | LEED Score (out of total points) | Case Study Author’s Commentary | ||

| Sustainable Sites | 5 /14 | The building has missed points on the Stormwater Management | ||

| Water Efficiency | 2 /5 | Scores low on this section and missed the points for water efficient landscaping as it is a rehabilitation project for a historic building and not a new development | ||

| Energy & Atmosphere | 10 /17 | Scores reasonably well considering it is a rehabilitation project for an existing building | ||

| Materials & Resources | 7 /14 | Scores well for building reuse, construction waste management, recycled content and durable building. However, has not received points for Resource Reuse | ||

| Indoor Environment Quality | 11 /15 | Seems reasonable except for Low Emitting Material: Carpet, as a new concrete floor was made for the building re-use | ||

| Innovation & Design Process | 5 /5 | Received maximum points including Exceptional Performance in water use reduction, Heat Island Effect, and Construction Waste Management. It has received an extra point based on the engagement of a LEED Accredited Professional |

Table.1: An assessment of the Salt building’s LEED Scorecard

Measuring social sustainability: Chris Landorf ‘s paper “Evaluating social sustainability in historic urban environments” from the Journal of Heritage Studies is used to evaluate the social sustainability of the rehabilitation of the Salt building.

| Social Equity | Access to services, facilities and opportunities | The new use of the Salt Building, a historical resource as a brewpub and cafeteria is an important component of community and social infrastructure of the SEFC neighbourhood | ||

| Social Coherence | Strength of networks, participation, identification and tolerance | The community and other stakeholders understand the heritage values of the site and the structure. The rehabilitation project has formed ties between the community and the government. However, there is no mention of the Coast Salish people in the project | ||

| Basic Needs | Objective satisfaction of basic needs | Rehabilitation of the Salt Building has provided employment opportunities for the people of SEFC neighbourhood It has added value to the overall built environment |

Table.2: An assessment of the Salt building’s social sustainability based on Chris Landorf’s evaluation criteria

Conservation Standards and Guidelines: The rehabilitation of the Salt building respects several principles of the Standards and Guidelines for the Conservation of Historic Place in Canada. The most pertinent standards that align with the rehabilitation of the Salt Building are Standard 7, 10 and 11.

| Standard 7: Evaluate existing condition | The existing condition of the character-defining elements of the industrial salt building such as clapboard siding, heavy timber trusses, windows and timber piles were analysed. Based on the evaluation, an appropriate intervention respecting the heritage values was followed. The external clapboard siding was retained while adding new insulation layer from inside, the timber trusses were strengthened using metal connectors, the existing windows were repaired and new openings were incorporated in the design to allow natural light and ventilation, the historic timber piles were extended using steel pile extensions to match exiting street level. | |

| Standard 10: Repair instead of replace | Most of the character-defining elements such as the gable roof with clerestory and other historic openings were retained instead of being replaced. Only the decayed timber members were replaced wherever required with new wooden members which were distinguishable by the colour and type of wood. A new signboard was replicated which was placed at the top of the gable roof as it was in the past, the replication was based on the archival photographs. | |

| Standard 11: Compatible addition | The overall character of the industrial building at a micro and macro level is enhanced by the appropriate conservation approach. For the building in order to meet heritage concerns especially preserving the exterior cladding, the structure’s wall insulation was done from the interior. This was also done to meet the LEED requirements and incorporate facilities for the new use of the building. The new work respected the visual compatibility in terms of style and material used for retrofitting. The interventions are not overpowering, bold or disrespectful, they merge well with the historic character of the industrial building. |

The rehabilitation of the building makes an excellent socio-cultural, environmental and economic sense and improves the overall character of the SEFC neighbourhood. The holistic approach followed for it ensures the continuation of the industrial memory of the neighbourhood and has protected the heritage building from being demolished, ending up in a landfill while enhancing the spirit of the place.

REFERENCES

Books/Book chapters/Journal articles

- Carroon Jean. (2010). Sustainable Preservation: Greening Existing Buildings. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN: 0470882131, 9780470882139

- Elefante, Carl. (2012). The Greenest Building Is…One that is already Built. Forum Journal 21.4. p.67-72

- Landorf, Chris. (2011). Evaluating social sustainabilty in historic urban environments. International Journal of Heritage Studies 17.5. p. 463-477

- Leifeste, Amalia; Stiefel, Barry. (2018). Sustainable heritage: merging environmental conservation and historic preservation. Abingdon, Oxon; New York, Routledge. ISBN 1138812196, 9781138812192, 9781138812185

- Ross, Susan. (2008). How Green Was Canadian Modernism, How Sustainable will it be? Docomomo Journal: Canada Modern 38.

- Ross, Susan. (2017). Keyword-Deconstruction Waste (Building). Discard Studies. Retrieved from https://discardstudies.com/2017/11/27/keyword-deconstruction-waste-building/

- Sorensen, Jean. (2010). Salt Building merges old and new in Vancouver. Journal of Commerce Retrieved from https://canada.constructconnect.com/joc/news/others/2010/03/salt-building-merges-old-and-new-in-vancouver-joc038154w

Policies and reports

- Canada Green Building Council. (n.d.). The Salt Building Project 11304. Retrieved from https://leed.cagbc.org/LEED/projectprofile_EN.aspx

- Parks Canada. (2010). Standards and Guidelines for the Conservation of Historic Places in Canada: a federal, provincial and territorial collaboration. Parks Canada. ISBN:9781100159539, 1100159533

- The City of Vancouver. (2006). Southeast False Creek Public Realm Program. Retrieved from https://vancouver.ca/docs/sefc/public-realm.pdf

Websites

- Acton Ostry Architects INC. (n.d.). Salt Building. Retrieved from https://www.actonostry.ca/project/salt-building-vancouver/

- Building Resilience. (n.d.). Salt Building Vancouver, British Columbia. Retrieved from https://buildingresilience.ca/case-study/salt-building/

- Glotman Simpson. (n.d.). The Salt Building Vancouver B.C. Retrieved from https://glotmansimpson.com/project/the-salt-building/

- Green Building Brain. (n.d.). Salt Building. Retrieved from https://greenbuildingbrain.org/buildings/salt_building

- Heritage Vancouver. (2002). Domtar Salt Building (1931). Retrieved from http://heritagevancouver.org/top10-watch-list/2002/9-domtar-salt-building/

- Recollective. (n.d.). The Salt Building. Retrieved from https://recollective.ca/projects/the-salt-building/

- Thompson, Stuart. (n.d.). City of Vancouver Archives. Vancouver Salt Company [at 85 West 1st Avenue]. Retrieved from https://searcharchives.vancouver.ca/vancouver-salt-company-at-85-west-1st-avenue-3

- Vancouver Heritage Foundation. (n.d.). Vancouver Salt Co. Building. Retrieved from https://www.vancouverheritagefoundation.org/location/85-w-1st-ave-vancouver-bc/

- Wilson, Stevie. (2013). You should know: a few cool things about the old salt building on False Creek. Retrieved from https://scoutmagazine.ca/2013/06/24/you-should-know-a-few-cool-things-about-the-old-salt-building-on-false-creek/

Feature image: add credit here.