The heritage in environmental sustainability: The rehabilitation of Still Creek, Vancouver, British Columbia

Case Study prepared by Nansen Murray, Carleton University

Keywords: Urban natural heritage; Steam rehabilitation; Rewilding cites; Daylighting; Hydrology and biodiverse ecosystems

LESSONS LEARNED

There are two main lessons learned through the rehabilitation of Still Creek. The first is the cost, daylighting is an expensive task, although it can be cheaper than replacing underground infrastructure. One cost which is enormous is land acquisition. If a stream has been channeled or culverted it takes far less space than a complex stream with meanders and a 5-50m riparian zone, as called for in provincial legislation (Lee + Associates et al., 2002, p.22). The first phase of rehabilitation on Still Creek avoided this issue by only using land already owned by the city and rerouting streets. The second phase calls for purchasing land from nearby landowners, the estimated cost in 2002 already ran into millions of dollars and the price of real estate in Vancouver has greatly increased in the 18 years since then (Lee + Associates et al., 2002, p.60).

Another lesson is unintended consequences of ecological health. It was not a stated goal of the rehabilitation of Still Creek to bring back Salmon to eastern Vancouver (Lee +Associates et al., 2002, pp.5, 84). Yet when the salmon did in 2012, and continued to until 2016, it was seen as a huge indicator of the success of the project (Munro and Schwark, 2014, p.4). In 2017 when Chloe Boyle conducted a community monitoring study of the ecological health of Still Creek, she discovered that the stream still displayed numerous qualities of a struggling urban stream (p.59). It was at this time that salmon stopped returning, but due to the lack of consistent monitoring it is unknown whether stream health declined or it was due to a massive decline in regional salmon populations (CBC News, 2019, Dec.1). Clearly, more systematic monitoring is necessary to determine success of the Still Creek project, and it would be wrong to think that the presence of salmon as the sole indicator of success and their disappearance as indicative of failure.

Importantly Still Creek shows that even where stream health is particularly degraded, and there is very little available space, with political will and community support, small projects can be successful at promoting the environmental, social and economic sustainability.

PRESENTATION

DESCRIPTION

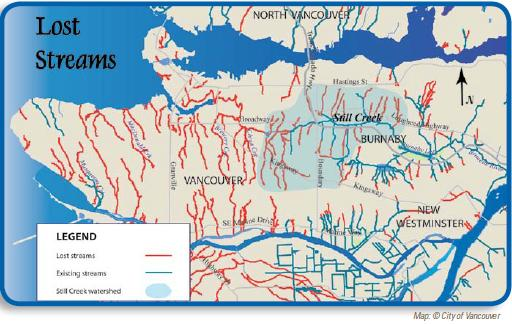

In order to understand the rehabilitation of Still Creek as a sustainable way to conserve natural heritage, it is necessary to examine the history of urban streams. The Industrial Revolution caused enormous increases in urban populations throughout Europe and North America. The localised water supply and waste water disposal, which was used previously was no longer adequate (Buchholz and Younos, 2007, p.5). Effluent which had formerly been channeled straight into streams and rivers—turning them into open sewers—was placed into underground sewers and culverts, along with the streams and rivers themselves. While this was a boon for city dweller’s health—cases of cholera and yellow fever declined significantly—it was catastrophic for aquatic life. The streams were effectively dead ecosystems and the larger water bodies, that they flowed into became dead as well (Hough, 1996, p.49). Sewage treatments developed as a technical solution to this problem, but it was too late for the streams already underground (Hough, 1996, 46). In the 20th Century the practice of channeling and culverting streams continued. The automobile meant that cites spread in all directions; streams and gullies took up valuable land that could be leveled and drained for ease of development (Boucholz and Younos, 2007, p.6).

This was the case for Still Creek, which was primarily buried in the 1950s. Although, almost unique for the City of Vancouver it was not completely hidden and sections of the main channel remained visible. However, sewage treatment and its place on the surface, did not mean that Still Creek was free from pollution or was a healthy ecosystem. Walsh et al. (2005) develop a concept they call, “the urban stream syndrome.” They state, “Consistent symptoms of the urban stream syndrome include a flashier hydrograph, elevated concentrations of nutrients and contaminants, altered channel morphology and stability, and reduced biotic richness, with increased dominance of tolerant species” (Walsh et al., 2005, p.707). Flashier refers to increased flow during rain events caused by the watershed catchment area being covered in impervious surfaces which quickly transfers the water—along with any pollutants—into sewers and creeks (Walsh et al., 2005, p.707).

Many issues associated with the hydrology of urban creeks stem from the impervious surfaces which surround them, and their reduced riparian zone. The riparian zone refers to the liminal space between the aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, which very biodiverse in a healthy ecosystem (Boyle, 2017, p.xi). According to Hough,

“The amount of water run-off is governed by the filtration characteristics of the land and is related to slope, soil type and vegetation…In forested land, run-off is generally absent…run-off from urban areas that are completely paved or roofed might constitute 85 per cent of the precipitation” (p.38).

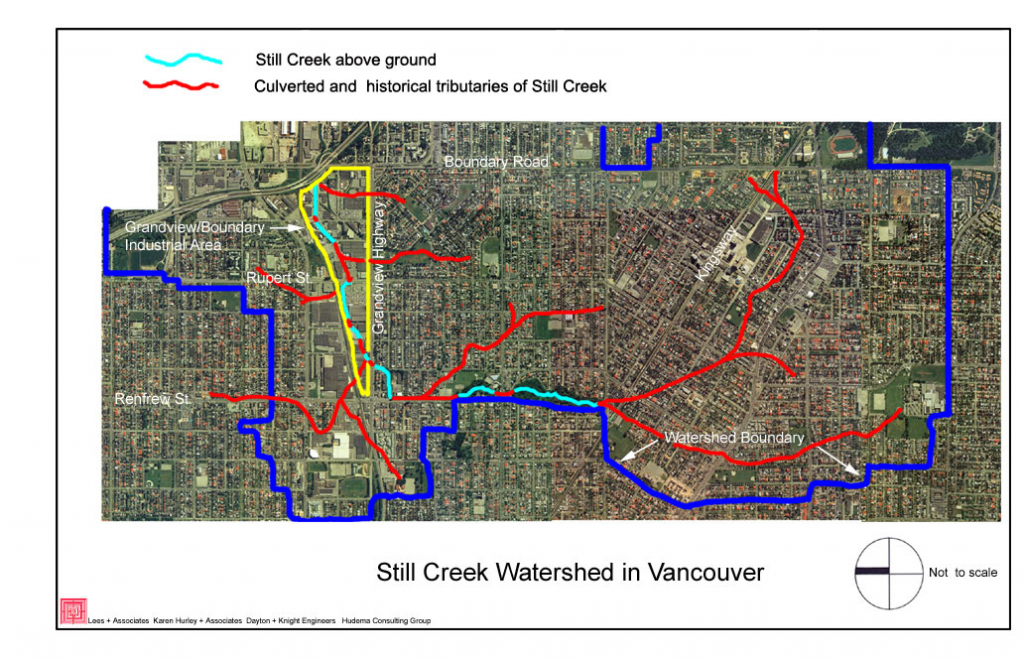

Because water is not filtered into the soil, evaporated to the air, or taken up by vegetation and subject to transpiration, numerous problems arise. Aquifers can be depleted, urban heat islands are exacerbated, pollutants have no chance to be filtered through the soil or broken down through the actions of bacteria and plants. Additionally, high flow rates destroy physical aquatic habitat, cause increased erosion and flooding (Walsh et al., 2016, p.401; Hough, 75, pp.77-8). The observations of Chloe Boyle (2017) demonstrate that Still Creek is symptomatic of ‘the urban stream syndrome’ (pp.4-5). In fact, the Still Creek watershed is 68% impervious and within the Grandview Boundary Industrial Area (GBIA) it is over 90% (Lee + Associates et al., 2002, p.93).

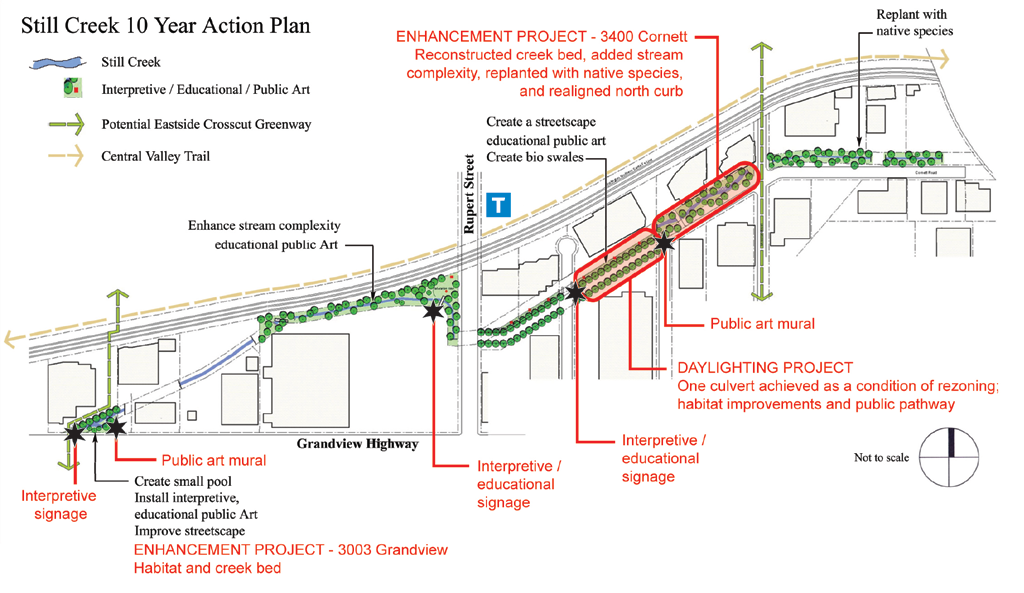

In 2002, the city of Vancouver endorsed the Still Creek Rehabilitation and Enhancement Study. The study laid out recommendations for the next 10 and 50 years, to address the numerous problems, laid out above, which affected the creek. The recommendations focused on five main goals: increasing education and connection to nature in local populations, creating pedestrian and bike paths along the creek, daylighting certain sections, storm-water management and improving water quality (Lees + Associates et al., 2002, pp.83-4). The latter two of these are accomplished through increasing creek complexity by adding meanders, side channels, pools, riffles, wetlands and replanting riparian zones with native species. Improved water quality and creek complexity together creates a situation where fish are able to once again use the creek. The plan also had separation between the watershed and the local level. The local level focused on 2 sections of creek outside of the GBIA and 5 sections within it (Lees + Associates et al., 2002, p.VII, XV).

Nine projects were completed between 2005 and 2011 within the GBIA. These include enhancement of stream complexity at all five sites, in addition to a 75m section which was daylighted near Cornnet Road. The increase in complexity included removing concrete flumes, reconstructing creek bed and banks, removing invasive vegetation and replanting with native species, and the creation of fish habitat (Vancouver Parks and Recreation, Still Creek, 2019). It also includes pathways, public art, and interpretive signage to make the creek a usable place for people (Munro and Schwark, 2018, p.4).

TIMELINE

| Time Immemorial | The lower mainland is occupied by various Indigenous groups (The Canadian Encyclopedia, 2019). | |

| 19th Century | Increasing contact with Europeans due to the fur trade (The Canadian Encyclopedia, 2019). | |

| 1886 | Vancouver chosen for the Canadian Pacific Railway Terminus (The Canadian Encyclopedia, 2019). | |

| 1914 | Still Creek Designated for storm-water runoff (Varty, et al., 2017). | |

| 1929 | A plan is developed to create a ‘parks and pleasure drive’ between Vancouver and Burnaby. The plan is dropped and much of the creek is culverted over the next decades (Varty, et al., 2017). | |

| 1932 | The last remembered salmon run on upper Still Creek (Varty, et al., 2017). | |

| 1950s and 60s | Increasing urbanisation leads to more pollution, and decreasing stream complexity (Varty, et al., 2017). | |

| 1980s | The city of Vancouver decides, based on changing values and community activism, that no more of Still Creek will be placed underground (Varty, et al., 2017). | |

| 1996 | Community groups led by Carmon Rosen develop initiatives to clean up sections of the creak such as Renfrew Ravine (Varty, et al., 2017). | |

| 2002 | The City of Vancouver endorses the Still Creek Rehabilitation and Enhancement Study, which recommends short- and long-term actions, in addition to local and watershed-based actions (Lees + Associates et al., 2002). | |

| 2005-2011 | Rehabilitation work carried out within the GBIA. This work includes, both enhancements to the steam ecosystem and infrastructure to improve human access and use (Munro and Schwark, 2018, p.4). | |

| 2012 | Chum salmon return to spawn in Still Creek for the first time since 1932 (Varty, et al., 2017). | |

| 2017 | Community monitoring of the ecology of Still Creek in the areas affected by rehabilitation (Boyle, 2017). | |

| 2018 | Funding for a salmon viewing platform approved by the city (Munro and Schwark, 2018, p.5). | |

| 2017-19 | Salmon fail to return for 3 years, although this is at a time when salmon populations across the west coast are in severe decline (CBC News, Dec. 1, 2019). |

STAKEHOLDERS

Still Creek exists within a complex web of responsibilities and desires. However, many stakeholders are quite passive only providing the framework under-which decisions are made. This is true of the B.C. and Canadian Governments (Lee + Associates, 2002, pp.22-3). The axis on which decisions are made is between residents, represented by community groups and the municipalities, on upper Still Creek where this project takes place that means the City of Vancouver. While Still Creek in part of the Brunette and Fraser River watersheds, and there is no single conservation authority who is responsible for the entire watershed, rather each municipality holds jurisdiction although the Fraser Basin Council facilitates cooperation between jurisdictions (BC Parks, 2019). During the process around the first phase of the Still Creek rehabilitation First Nations were not involved, however, there is some indication that may be changing with the Musqueam being involved in another rehabilitation, that of Tatlow Creek (Tatlow and Volunteer Creek, 2019).

- First Nations: Coastal Salish peoples, including the Musqueam, Tsliel-waututh and Squamish First Nations.

- Governments: The Canadian Government through the Department of Fisheries and Oceans; the Government of B.C. through legislation such as the Fish Protection Act and the Water Act; the Greater Vancouver Regional District is responsible for storm-water management; the City of Vancouver; the City of Burnaby; Vancouver Parks and Recreation.

- Community and non-governmental organizations: Still Moon Arts Society; Evergreen; Silva Forest Foundation; Collingwood Neighborhood House; Friends of Renfrew Park; Friends of Renfrew Ravine; and the Friends of Falaise Park.

- Owners/users: Residents and property owners in the Still Creek watershed; Businesses which own property in the GBIA.

- Consultants: Numerous consultants have worked on reports such as Lee + Associates et al., and AXYS Environmental Consulting Ltd, in addition to companies which have carried out the work on the creek enhancements.

- Universities: University of British Columbia; British Columbia Institute of Technology

HERITAGE

Natural heritage: Natural heritage is often not apparent when an urban ecosystem is as degraded as Still Creek was in the 1960s, but in the 1970s society began to realise the value in maintaining natural heritage even in urban environments. This sentiment prevented Still Creek from following the majority of creeks in Vancouver and disappearing (Varty, et al., 2017). Heritage is the message from the past projected into the present, therefore it often means looking backwards. Many authors therefore, call stream rehabilitation: stream restoration (Walsh et al., 2016, p.399; Wohl, Lane and Wilcox, 2015, p.5975). Rehabilitation is used in this case study because it is used by the City of Vancouver, and because, following the Canadian paradigm in heritage conservation, rehabilitation looks to future use and value (Standards and Guidelines 2010, p.16). For Still Creek and urban water courses generally, this is more appropriate because a return to an undeveloped state is impossible. The hydrological cycle is a large system which relies on soil filtration and vegetative uptake of water over the watershed as a whole. The percentage of impermeable surfaces in urban environment precludes any true restoration (Walsh et al., 2016, p.402; Zandbergen, 1998, p.170). The high imperviousness of the watershed continues to threaten the viability of the natural heritage rehabilitation as high flow events can cause the erosion of fish habitat and drown riparian vegetation (Boyle, 2017, p.52).

Despite this negative view of the restoration of natural heritage, Leticia Leitao (2017) wrote that although natural heritage is often completely siloed from cultural heritage, it should not be. She suggests that to better understand our heritage,

“We need to develop new concepts that build upon the full continuum of humans’ interactions with nature, ranging from areas set aside to preserve nature from significant direct intervention by humans; to biocultural landscapes, representing intertwined holistic systems that have been shaped by human management over long periods of time” (Leitao, 2017, p.208).

This understanding opens up the possibility that Still Creek has important natural heritage, even though it has been managed and changed beyond recognition in 130 years.

The rehabilitation of Still Creek aimed to, and was successful at restoring many natural elements. Salmon are a keystone species on the northwest coast of North America. Salmon bring the resources of the ocean back to the creeks where they were born. Their bodies provide food to numerous predators including humans, and when they decay the nutrients accumulated through their lives go into the earth (MacDuffee and Scott, 2018). This is one reason that the temperate rainforest is one of the most biomass dense ecosystems in the world (Buma, Krapek and Edwards, 2016, p.844).

The riparian zones planted between 2005 and 2011 are not yet mature ecosystems, but have the potential to be amongst the most biodiverse in Vancouver (Lee + Associates, 2002, p.19; Boyle, 2017, p.51). There is little data available on the use of the stream corridor by birds although they are also important indicators of ecosystem health. Anecdotal evidence suggests Still Creek is used as a travel route by numerous species (Boyle, 2017, p.20). Given the scale of the project the rehabilitation has been a success at returning natural heritage to east Vancouver.

Cultural heritage: The cultural heritage in a rehabilitation of a stream’s natural elements is not overt. However, the return of salmon to Still Creek along with the use of the stream for recreation and travel by locals connects the creek back to its function in the early 20th century. Still Creek was used for recreation, including salmon fishing and swimming. The dislocation felt by residents as the creek was developed, is clearly seen in Geraldine Knibb’s recollections of the 1950s. ““I just love to talk about when we lived down on the creek, and there’s not one soul living that I can laugh and say, ‘remember the good days,’” she says. “Nobody’s left”” (Fuller-Evans, 2015). Still Creek also functioned as liner landscape feature leading from Vancouver to Burnaby, and was considered for a scenic parkway between the two cities (Varty, et al., 2017). The rehabilitation has recreated this link—although not in full—and for pedestrians and cyclists rather than automobiles.

The return of the salmon is important culturally for the city, for the general population and especially for the Indigenous population—for whom Salmon was a key resource and spiritual species. Susan Buggey (2007) writes about the cultural values of natural resources in her work, “Associative Values: Exploring Nonmaterial Qualities in Cultural Landscapes.”

“…they [associated cultural landscapes] are defined by cultural values related to natural resources. Enduring use of the land and interactivity of nature and culture illustrate the values attached to place. In language, narratives, sounds, ceremonies, and social customs are found the cohesive evidences” (Buggey, 2000, p.23).

A quotation in The Tyee from J.B. MacKinnon, a curator at the Museum of Vancouver, helps to illuminate this connection,

“Vancouver might be the only big city on earth where another species, salmon, is so much a part of our urban identity…We’re still salmon people here, and we can use that connection to revive our lost salmon streams (Holdsworth, 2014).

The strong support for the rehabilitation of Still Creek amidst the community, as illustrated by participation in the numerous stream keeper groups, shows the strong connection to the natural environment. Natural heritage is culturally important because the community says it is.

For Indigenous people the connection is even more overt. The normal state of the land for land surrounding Vancouver before settlement by non-Indigenous people is for the numerous creeks to have 100 000 returning salmon (Holdsworth, 2014). There are numerous spiritual stories which recount this importance, “the head, bones, and entrails are separated from the flesh of the salmon. The fish is carried by twins…to the river’s edge where the chief thanks the Salmon People and returns the remains to the water” (Laiwanette, 2019). The loss of the fish is felt in more modern stories, “a woman witnesses the ghosts of salmon floating in and out of the water. She asks them what is the matter and they tell her that the humans have stopped bringing their bones to the water and the salmon are unable to return home” (Laiwanette, 2019). This suggests that First Nations would be incredibly interested in the Still Creek rehabilitation, although I have not found any reference to their reaction.

SUSTAINABILITY

Environmental sustainability: Still Creek lost almost all of its environmentally sustainable elements over the course of the 20th Century. The municipal projects in the early 21st Century have sought to return sustainability to the watershed. Still Creek contains the only un-modified section of nature in Renfrew Ravine and it remains undeveloped as an urban nature preserve (Lee + Associates, 2002, p.12). By expanding the amount of riparian zone in Renfrew Park and the GBIA, which contains a variety of native species, such as alder, willow and evergreen, rather than the mono-culture of the invasive Himalayan Blackberry, which dominates in non-habilitated stretches of stream. Replacing shrubs with large woody trees has the added benefit of sequestering additional carbon from the atmosphere (Hough, 1996, p.15). Having a variety of native flora makes the vegetation more resilient to climatic change, in addition, it supports a wider variety of both aquatic and terrestrial species of animals.

The addition of wetlands, riparian vegetation, meanders and naturalised stream beds to Still Creek serves multiple purposes. The primary purpose is to slow the removal of storm-water from the system to prevent flooding, and help improve water quality (Walsh et al. 2016, p.399). The methods employed to that end are in line with Best Management Practices for water management. These are designed to facilitate the “Protection of life and property (flood and erosion control); Protection of habitat (erosion and sedimentation), and, Protection of water quality” (Lee + Associates, 2002, p.89). The removal of culverts and concrete flumes allows water to filter through the soil and evaporated to the air; the riparian vegetation absorbs water from where it can then transpire over a much longer time period; and wetlands pool larger bodies of water, allowing pollution to sink to the bottom, and support unique biomes in their own right. By holding water in the ecosystem for an increased amount of time, it moves toward a sustainable hydrological system that replenishes aquifers, nourishes vegetation and mitigates the urban heat island effect through evaporation and transpiration (Walsh et al., 2016, pp.400-2).

Social sustainability: The rehabilitation of Still Creek benefits the social fabric of the neighbourhood in a number of ways. It turned the creak into a sustainable transportation corridor focusing on linking Skytrain stations to pedestrian and bike paths. The path is surrounded by vegetation where the creek right-of-way is large enough, and there are park benches at numerous intervals, turning the creek into an inviting place to use. Public art displays and interpretative signs bring an educational element to the space encouraging a knowledgeable population, who can see the value in the rehabilitation of Still Creek (Lee and Associates, 2002, p.5). Within the GBIA Still Creek has become the only green-space, this means that employees who work in the industrial area are able to psychologically recharge in a natural area. This improves the viability of the GBIA to retain employees, and give them a sustainable way to get to work (RivInstitute, 2012; Cheung, 2019)

Chris Landorf (2011) in her article, “Evaluating social sustainability in historic urban environments” writes that socially resilient communities’ function through social networks, common values and pride and identification with the community. These qualities give work together and promote social cohesion (Landorf, 2011, p.569). The large number of stream-keeper groups and community initiatives show Still Creek to be a focal point to increase social cohesion.

Economic sustainability: The economic sustainability of Still Creek is largely unrecognised by the City of Vancouver, however, there are examples of other daylighting projects, which can show the various ways rehabilitating waterways can benefit the economy. The first stems from a stated goal of the Still Creek rehabilitation: flood management. In Kalamazoo the municipality expropriated the land, but added financial incentives, such as assuming liability for flooding. The city would then need to engineer the rehabilitated stream to accommodate a 500-year flood, or similar as in Kalamazoo McGrath, 2014, p.16). The rehabilitation in Kalamazoo also is seen a revitalisation of the neighbourhood, attracting more people and therefore money to businesses (Buchholz and Younos, 2007, p.17). While this sort of incentive along with public pressure for companies to be socially responsible could lower the cost of rehabilitation, it is important for Still Creek to not lose its focus on ecological health, in which it outpaces Kalamazoo (Buchholz and Younos, 2007, p.18). These projects are designed around these principals and use far more land than the current project of Still Creek, but these benefits likely exist to a lesser degree.

United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): There are clear links between Still Creek rehabilitation and the United Nations SDGs. However, I will focus on two. The first is SDG 14: Life Below Water. The links here are clear even though SDG 14 focuses heavily on oceans, and sustainable fish harvesting this is seen in target 14.2 among others (UN, SDG 14, target 14.2). This is because salmon are anadromous fish, meaning they spend part of their life in the ocean before swimming back to the creek of their birth and spawning before dying. Salmon are a commercial fish, which is also in population decline throughout the west coast. Therefore, providing spawning habitat is a valuable contribution to salmon conservation. The number of fish present in Still Creek compared to the cost of the rehabilitation, determines that if numbers are the only metric the money would be more useful elsewhere.

However, creating an ecosystem in an urban setting where salmon and other flora and fauna can thrive, increases citizen appreciation of their link to the natural world. This education provided by functioning city ecosystems combined with the environmental sustainability discussed above strongly links Still Creek to SDG 11 Sustainable Cities and Communities, specifically target 11.7 and 11B, which advocate for access to green-space and resilience to climate change respectively (UN, SDG 11, target 11.7, 11B).

MEASUREMENT

Two sources are used to assess the success of the Still Creek rehabilitation. The first is the Still Creek Rehabilitation and Enhancement Study, which contains goals for the project. “The science and practice of river restoration,” by Ellen Wohl, Stewart Lane and Andrew Wilcox (2015), provide principles for the practice of rehabilitation of waterways and issues to avoid to have a successful project.

REFERENCES

Book chapters/Journal articles/Theses

- Boyle, C. (2014). Vancouver stream restoration practices: Piloting a community-based monitoring framework along Still Creek [masters report]. Simon Frazer University.

- Buchholz, T., & Younos, T. (2007). Urban Stream Daylighting Case Study Evaluations. Virginia Water Resources Research Center: Virginia Tech.

- Buggey, S. (2000). “Associative Values: Exploring Nonmaterial Qualities in Cultural Landscapes.” APT Bulletin: The Journal of Preservation Technology, 31, 4, 21-27.

- Buma, B., Krapek, J., & Edwards, R. (2016), “Watershed-scale forest biomass distribution in a perhumid temperate rainforest as driven by topographic, soil and disturbance variables.” Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 46, 6, 844-854.

- Hough, M. (1995). Cities and Natural Process. London: Routledge.

- Landorf, C. (2011). “Evaluating social sustainability in historic urban environments.” International Journal of Heritage Studies, 17, 463-477.

- Leitao, L. (2017). “Bridging the Divide Between nature and Culture in the World Heritage Convention: An Idea Long Overdue?” The George Wright Forum, 34, 2, 195-210.

- McGrath, D. (n.d.). Daylighting in Halifax’s Urban Core: A case study-based analysis of the proposed daylighting of Sawmill River in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. Master’s Project Dalhousie University. Accessed from https://ecologyaction.ca/files/images-documents/file/Coastal/Water/Daylighting%20Report-Darryl%20McGrath%20PLAN5000.pdf.

- Robertson, J. (2019). “British Columbia.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. Accessed from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/british-columbia.

- Spatari, S., Yu, Z., & Montalto, F.A. (2011). Life cycle implications of urban green infrastructure. Environmental Pollution, 159, 2174-2179.

- Walsh, C., et al. (2016). “Principals for urban stormwater management to protect stream ecosytems.” Freshwater Science, 35, 398-411.

- Walsh, C., et al. (2005). “The urban stream syndrome: current knowledge and the search for a cure.” Journal of the North American Benthological Society, 24, 3, 706–723.

- Wohl, E., Lane, S., & Wilcox, C. (2015). “The science and practice of river restoration.” Water Resources Research, 51, 8, 5974-5997.

- Zandbergen, P. (1998). “Urban watershed ecological risk assessment using GIS: a case study of the Brunette River watershed in British Columbia, Canada.” Journal of Hazardous Materials, 61, 163-173.

Policies and reports

- Lees + Associates, Karen Hurley + Associates., Dayton + Knight Engineers., & Hudema Consulting Group. (2002). Still Creek Rehabilitation and Enhancement Study. City of Vancouver Community Services, Planning Department, City Plans. Accessed from https://vancouver.ca/files/cov/still-creek-rehabilitation-enhancement-study.pdf.

- Munro, K., M. Schwark. (2014,Aug. 28). Sill Creek Enhancement -Project Funding. City of Vancouver. Accessed from https://council.vancouver.ca/20140916/documents/a9.pdf.

- Munro, K., M. Schwark. (2018, Mar. 23). Administrative Report: Still Creek Enhancement Project. City of Vancouver. Accessed from https://council.vancouver.ca/20180417/documents/a10.pdf.\

- Parks Canada. (2010). The Standards and Guidelines for the Protection of Historic Places in Canada. Accessedfrom https://www.historicplaces.ca/media/18072/81468-parks-s+g-eng-web2.pdf.

- United Nations (2015). Sustainable Development Goal 11. Accessed from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg11.

- United Nations (2015). Sustainable Development Goal 14. Accessed from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg14.

Websites

- BC Parks. (2019). Fraser River. Provence of British Columbia. Accessed from http://www.env.gov.bc.ca/bcparks/heritage_rivers_program/bc_rivers/fraser_river.html.

- Cheung, C. (2019, Feb 21). “Never Give Up on Any Waterway.” TheTyee.ca. Accessed from https://thetyee.ca/News/2019/02/21/Burnaby-Waterways-Daylighting-Creeks-Streams-Buried/.

- City of Vancouver. Tatlow and Volunteer Park stream restoration. (2019). Accessed from https://vancouver.ca/parks-recreation-culture/tatlow-and-volunteer-park-stream-restoration.aspx.

- East Vancouver’s urban salmon stream sees no returning fish in 3 years. (2019, Dec. 1) CBC News. Accessed from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/still-creek-salmon-1.5380465.

- Fuller-Evans, J. (2015). Still Creek History in Burnaby Now [web log post]. http://brentwoodstation.blogspot.com/2015/10/still-creek-history-in-burnaby-now.html.

- Holdsworth, P. (2014). Vancouver’s Lost Salmon Steams Wriggle Back to Life. TheTyee.ca. Accessed from https://thetyee.ca/News/2014/07/05/Lost-Salmon-Streams-Vancouver/.

- Laiwanette. (n.d.). “Return to the Water: First Nations Relationship with Salmon.” The Hydraulic blog. Accessed from http://www2.laiwanette.net/fountain/return-to-the-water-first-nations-relations-with-salmon/.

- MacDuffee, M., & Scott, D. (2018). “Wild Salmon Program.” Raincoast Conservation Foundation. Accessed from https://www.raincoast.org/projects/wild-salmon/.

- RivInsitute. (2012). Salmon Return to Still Creek (video). YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7XWH4us7M8w.

- Still Creek Enhancement. (2019). City of Vancouver. Accessed from https://vancouver.ca/home-property-development/still-creek-enhancement.aspx.

- Varty, F., Mak, J., Dou, M., & Wellian, J. (2017). The Restoration of Still Creek: How the Salmon Returned [web log post]. https://blogs.ubc.ca/stillcreek/.

Feature image: The Still Creek Streamkeepers are a group of neighbours and citizen scientists who help take care of Still Creek and Renfrew Ravine, with the support of Still Moon Arts Society. Image source: https://stillmoonarts.ca/streamkeepers/