The Saskatchewan Ecomuseum Initiative: A Look into the Sustainable Initiative of the “museums without walls”

Case study prepared by Julie Boudrias, Carleton University

Keywords: Ecomuseum, sustainability, living heritage, conservation, community, counter-museum

LESSONS LEARNED

This case study shows that museums are far more than relicts of the past on display in a grand building, museums are a tool for education, culture sharing and preservation of our land and communities (Power). Museums do not have to be extravagant structures that we must travel to, they can be in our communities, telling stories and preserving objects of local histories. Ecomuseums press the fact that culture can be the basis for a museum and that the concept is open to interpretation, it is the community that defines living heritage (Power).

Traditional museums, although beneficial in many ways, have a reputation brimming with controversy that is deeply tied to colonialism (CBC Radio). Many traditional Museums are large, intricate structures that hold stolen artifacts; this is neither sustainable nor is it community-based (CBC Radio). Ecomuseums differ from traditional because they only include local living heritage, and sustainability is a key factor in their development (Power). All museums have a responsibility to ensure they are giving back to an equal or greater amount than they are taking from the land and the people of that land (Power). Traditional museums have the capacity to be more sustainable in all areas and should be held to that standard (Power).

Further, this case study proves that there are ways that provinces can work seamlessly with small communities through initiatives such as this. However, implementing a project takes years and massive organization and planning, many have been in the works for close to a decade and are still in progress (north central Regina example). It is essential that federal, provincial and small community groups work together to ensure every ecomuseum is given the right amount of time and attention in order for them to be brought to life.

This presentation provides a simplified description of the case study, including images and preliminary findings and information.

DESCRIPTION

An ecomuseum is a community-run initiative whereby a structure, site, place or area are protected by the local community and is turned into a museum (Heritage Saskatchewan and Museums Association of Saskatchewan, 7). Ecomuseums combine online projects, objects, sites, structures and wildlife habitats with the traditions, practices, and customs of living heritage (Heritage Saskatchewan, and Museums Association of Saskatchewan, 7). It is not a museum in the traditional sense, in fact in many cases there is no building at all, this is why ecomuseums are sometimes referred to as “museums without walls” (Sutter et al., 7). Traditional museums are incredibly valuable learning tools around the world, they teach us about the past of different cultures and how society was formed as a result (CBC Radio). However, despite their significance, traditional museums are often faced with controversy for their stolen artifacts and their refusal (in many cases) to return them (CBC Radio). An ecomuseum is, in a sense then, a counter-museum, it aims to take all the benefits of the traditional museum and add sustainable practices and community involvement to create a new form of museum (Sutter et al., 7).

The ecomuseum concept was developed in France in the 1970s, the developers wanted to reimagine the traditional museum while keeping its core principles (Heritage Saskatchewan, and Museums Association of Saskatchewan, 7). The purpose of an ecomuseum is to create sustainable social and economic development by using in situ conservation and interpretation of natural and cultural heritage (Heritage Saskatchewan, and Museums Association of Saskatchewan, 7). It is meant to be developed by the community for the community, It serves as a way to bring a community together through sustainable interaction with living heritage, and creating strong social connections through cultural sharing (Sutter et al., 2).

In situ means from a natural or original source, in this context, it means that the items or sites used for the museums are already in that area and not moved (Merriam-Webster). Once the idea gained popularity it was brought to the attention of Glenn Sutter, the curator of human ecology at the Royal Saskatchewan Museum, from here the idea spread and the Saskatchewan ecomuseum initiative was created (GlennSutter.com). The Saskatchewan Ecomuseum Initiative was created with the purpose of creating sustainable museums as well as to demonstrate how existing museums can be more sustainable in practice and in their communities (Heritage Saskatchewan, and Museums Association of Saskatchewan, 7). Several ecomuseums are currently in existence or are in the process of being created, some of these include:

- North Central Regina: the community would like to make the area into an ecomuseum and are in the process of development

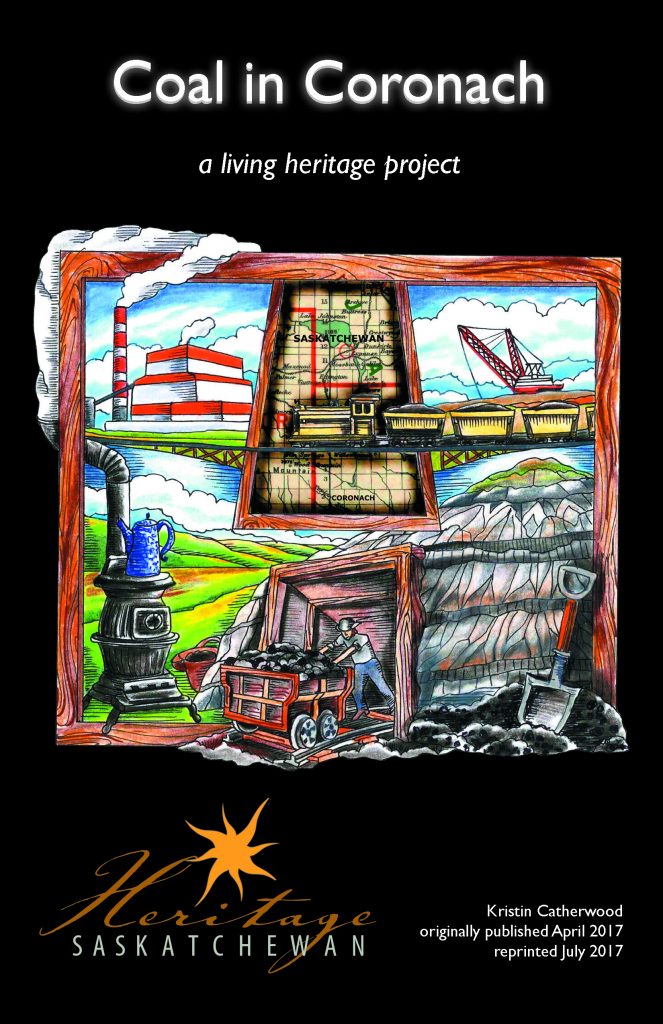

- Coal in Coronach Living Heritage Project: a pamphlet and two videos made available online about the importance of the coal industry in the town of Coronach, Saskatchewan (Coal in Coronach)

- Val Marie Elevator Living Heritage Project: A retired grain elevator in Val Marie, Saskatchewan that is now popular for tourists, it has also attracted many artists to the area

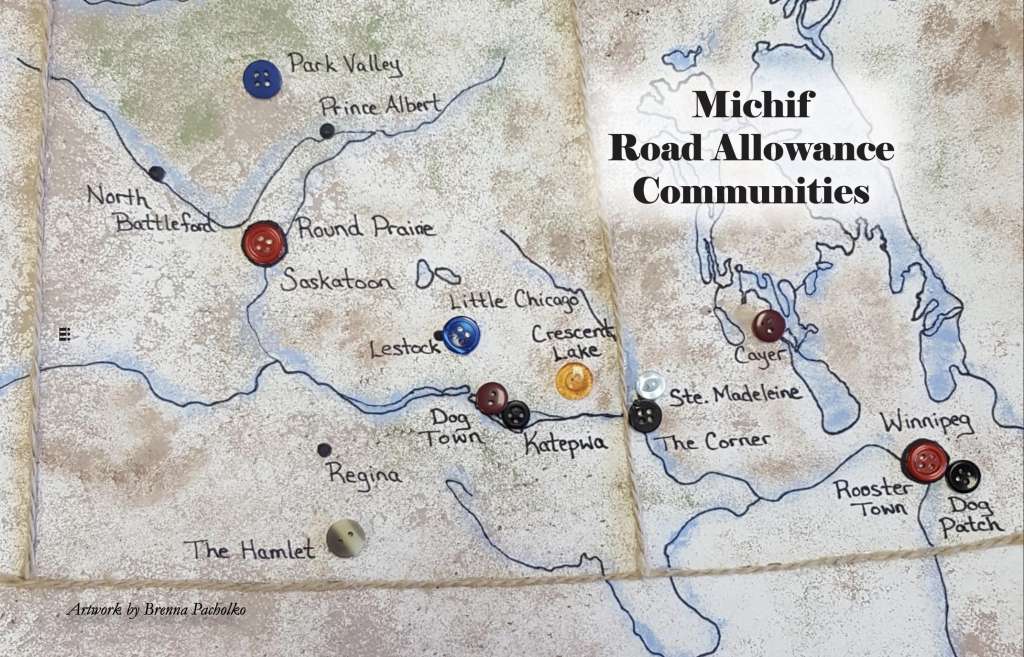

- gee meeyo pimawtshinawn (It Was a Good Life) booklet – Saskatchewan Métis Road Allowance Memories living heritage project: a booklet available online, it consists of stories by Indigenous people about places they grew up (Métis Road Allowance Memories)

TIMELINE

Place Timeline

- 1972: the ecomuseum concept was developed in France (Sutter & Kincaid & Fletcher, 2)

- 2011: European popularity of the ecomuseum reaches Saskatchewan. Glenn Sutter from the Royal Saskatchewan Museum sent an inquiry for interest in creating ecomuseums and received positive responses from over 15 locations (Power)

- 2012: the Saskatchewan Ecomuseums Initiative (SEI) was established (Heritage Saskatchewan)

- 2013: Ecomuseum Planning Framework established (Heritage Saskatchewan)

- 2012-present: ecomuseums being established all over Saskatchewan such as Indian Head, Wolseley and Nipawin communities (Power)

Project Timelines

- 2014-present: North Central Regina ecomuseum

- 2014: project was presented to the community, several community members were interested

- Present: little is known about where the project currently stands, projects of this scale take time, the COVID-19 pandemic likely slowed the process as well

- (North Central Regina)

- 2016-2017: Coal in Coronach Living Heritage Project

- 2016-2017: the project began filming for the documentary and the booklet began, both heavily involved locals (Catherwood)

- February 2017: the idea is introduced to the public via news article, coal has a significant history in Coronach and is the main employment line for many. With coal becoming increasingly controversial, the town wanted a way to remind the community of its legacy and continued importance to the town (Catherwood)

- April 12th, 2017: Coal in Coronach Living Heritage Project presented (Coal in Coronach)

- 2018: Val Marie Elevator Living Heritage Project

- 2015: National Trust for Canada placed wooden grain elevators on the Most Endangered Places list

- January 2018: the idea was launched and work began, community members were interviewed by high school students over several months and then were converted to the booklet

- September 15, 2018: Val Marie Elevator Living Heritage Project launched

- (Val Marie)

- 2017-2019: Métis Road Allowance Memories Living Heritage Rpoject

- Fall 2017: Kristin Catherwood gave a presentation about documenting living heritage to an indigenous studies class, their interest inspired her and the idea for this project was born

- September 2018: the project was launched, from here, stories and art were collected for the booklet

- April 5, 2019: the official launch of gee meeyo pimawtshinawn (It Was a Good Life) booklet

- (Métis Road Allowance Memories)

STAKEHOLDERS

Every community that has an ecomuseum becomes a stakeholder because the museum is run by the community. According to an interview by Kevin Power with Glenn Sutter (a key creator of the initiative), it appears that some stakeholders were greater contributors than others (Power). Glenn Sutter, curator of human ecology at the Royal Saskatchewan Museum (RSM), is the one who introduced the idea of ecomuseums to Saskatchewan, the RSM and Heritage Saskatchewan are behind many of the projects created thus far (Power). They function as consultants and researchers for projects and offer help where needed, however they only intervene where necessary as to not jeopardize the importance of them being community-run (Power). Dr Glenn Sutter and Kristin Catherwood are included because they are heavily involved in several projects, either contributing in the organization of it or researching about a project or ecomuseums in general, they both come up often throughout this case study. The communities associated with the four examples are:

- North Central Regina (North Central Regina)

- The community of Val Marie (Val Marie)

- The community of Coronach (Coal in Coronach)

- Michif Road Allowance Communities (Métis Road Allowance Memories)

Provincial and federal organizations (Massey)

- Royal Saskatchewan Museum

- Heritage Saskatchewan

- Museums Association of Saskatchewan

- SaskCulture

- The Saskatchewan-United Nations Regional Centre of Expertise (RCE) on Education for Sustainable Development

- Heritage Canada the National Trust

Indigenous Contributors (Massey)

- Raven Consortium inc. (an association of First Nations consultants).

Researchers

- Glenn Sutter

- Kristin Catherwood

HERITAGE

Living heritage are the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills, instruments, objects, and cultural aspects of what people (usually groups or communities) understand is their cultural heritage (UNESCO). This is also called intangible heritage and it is passed on through generations and is in constant circulation through time as communities use them to connect with the environment, nature, and their histories (UNESCO). Living heritage provides people with a sense of self, this can lead to respect of different cultures (UNESCO). This is especially relevant to group such as the Saskatchewan Ecomuseum Initiative because they focus on rural heritage rather than urban (Heritage Saskatchewan). Rural areas are where you find communities that are closely tied to their heritage, something that is seldom seen in urban spaces (L. Massey, 16). Ecomuseums are beneficial to both natural and cultural heritage because it encourages conversations about sustainability and how communities can come together and create positive change (L. Massey, 24).

The sites used in ecomuseums already exist and are valued for what they already offer, nature is not damaged in the process, additionally, wildlife conservation areas are protected through these museums (L. Massey, 31-32). By educating the community of the importance of these areas and how they connect to their history, it becomes important to their heritage, meaning they will feel a responsibility to protect it, this could lead to other areas being protected as well (L. Massey, 32). Further, culture can be preserved through the practice of culture sharing, when people tach about their cultures through an ecomuseum, it is educating those interacting with the museum, this education leads to community bonding and the creation of culturally sensitive workspaces (Massey).

Each community initiative presents diverse interpretations of heritage. For the Val Marie living heritage project, it is a physical structure that represents an important aspect of the community (Val Marie). It is something that the community chose to preserve for its agricultural significance during its operation (Val Marie). It became increasingly important to the community after the mill was deemed endangered due to the rapid deterioration and destruction of wooden grain mills across the province (Val Marie). An unexpected reaction to the mill has been its attraction for artists who visit the area as tourists and new residents (Power). In contrast to this, the Métis road allowance memories living heritage project had a different approach to their ecomuseum in which storytelling and art was their avenue (Métis Road Allowance Memories). This project understood the value of lived experiences from a larger community and found a sense of self in the histories and artistry of the people of the Michif communities (Métis Road Allowance Memories).

SUSTAINABILITY

Environmental Sustainability: The physical sites or structures used to create an ecomuseum already exist, construction is not required for an ecomuseum, meaning the land is protected (Sutter et al). Any physical objects or artifacts are not moved, where they are found is where the ecomuseum is created (Heritage Saskatchewan). An essential element of the framework that was created by the Saskatchewan Ecomuseum Initiative was environmental sustainability (Heritage Saskatchewan). It is required that ecomuseums are more beneficial to the environment than damaging, ecomuseums are themselves environmentally sustainable (Heritage Saskatchewan). The framework created even goes a step further and provides suggestions on how existing traditional museums can be more sustainable and community oriented.

Social Sustainability: The Saskatchewan Ecomuseum Initiative also relies heavily on the local communities for development, expertise and management of ecomuseums, they are mean to represent the community (Heritage Saskatchewan). In order for the community to be involved, they work together to create and maintain exhibits, this requires a great deal of organization and social interaction (L. Massey, 6). Beyond its creation, an ecomuseum itself would attract local and outside visitors which benefits the community but especially seniors as it promotes healthy active living options (Massey). Ecomuseums strengthen social bonds by bringing people together, making the town a more welcoming and tolerant place (Massey).

Cultural Sustainability: The cultural benefits of an ecomuseum are extensive, ecomuseums are a reflection of the community and its values, by placing such importance on a piece of living heritage, people are encouraged to share and absorb the cultures of others (L. Massey, 15). An ecomuseum is an expression of culture in itself, by showing off what the community views as an important cultural site, it is sharing a culture with visitors, in turn, those visitors will learn of the cultural significance and possibly share their own or bring the ecomuseum concept back home to create their own (Sutter et al). The Saskatchewan Ecomuseum Initiative has several main goals but a major one is ensuring the community where the ecomuseum is being created has the most influence over the project because it is meant to give the community reasons to be proud of where they are from, ad pride is essential to a sense of culture (L. Massey, 23-26).

Economic Sustainability: Due to the fact that ecomuseums are community-based and locally run, it creates jobs which directly benefits the community (Power). It also attracts visitors from near and far which brings in revenue to the ecomuseum as well as local businesses such as restaurants, stores, and hotels (Power). The Val Marie Grain Elevator Ecomuseum has gained popularity for artists to visit and even move to the community, proving that ecomuseums can bring in people from diverse backgrounds and for many reasons (Power). Finally, the information for the ecomuseums mentioned are widely available online and due to it being a relatively new concept, they come up first, making it more liely that people will chose to visit those places (Power).

MEASUREMENT

The Saskatchewan Ecomuseums Initiative (SEI) released a framework for developing an ecomuseum, they provide a list of indicators of a well-functioning ecomuseum (SEI, 18 & Appendix 1). This list is extensive, but it has four main pillars; levels of activity, levels of use/participation, levels of interactions, communication, transaction and exchange, and levels of representation (SEI, 18). In order to determine their success, the three completed ecomuseums mentioned above will be measured under these criteria.

Coal in Coronach

| Levels of activity/number of things going on (how effective are we at delivering activities that support engagement with our purposes?) (SEI, 18) | The booklet and the documentary are the only methods currently in use for engagement with the project, however the online presence means it will never end and factors like weather and distance do not have an impact |

| Levels of use/participation (how effective is the programming we are providing at reaching a wider audience?) (SEI, 18) | Due to its online presence, this project has an endless reach for wider audience |

| Levels of interactions, communication, transaction and exchange – the relationship between people and activities and the establishment of critical mass (what is the depth and mode of participation in our programming?) (SEI, 18) | This project involved community and provincial/federal participation, the project was introduced by stakeholders and the community helped bring it to life. The community of coronach were involved in the film and booklet by conducting or staring in interviews, it |

| Level of representation – how the ecomuseum is projected and discussed in the outside world (what is the perception of this initiative and our programming in the local and wider communities? How widespread is the awareness?) (SEI, 18) | The online booklet was posted to Heritage Saskatchewan The promo video and accompanying documentary, which are posted for free on YouTube, have a combined 5 thousand views (Heritage Saskatchewan YouTube) |

Val Marie Grain Elevator

| Levels of activity/number of things going on (SEI, 18) | The grain elevator is open to the public to visit and the booklet created is available online making it a high activity ecomuseum |

| Levels of use/participation | This project has both online and physical access |

| Levels of interactions, communication, transaction and exchange – the relationship between people and activities and the establishment of critical mass (what is the depth and mode of participation in our programming?) (SEI, 18) | The booklet includes interviews of people local to the grain elevator and their memories of it, these interviews were conducted by local high school students The grain elevator itself is managed and cared for by the community |

| Level of representation – how the ecomuseum is projected and discussed in the outside world (SEI, 18) | This project has the potential for a massive audience due to the online presence of the booklet The grain elevator has become popular for visitors due to the dwindling number of remaining grain elevators in the province, it also has attracted artists to the area Overall, this project has a wide audience who all have a positive perception of it |

Métis Road Allowance Memories

| Levels of activity/number of things going on (SEI, 18) | It is very easy to interact with this ecomuseum, although it is only one booklet, it provides the viewer with an in-depth look at the lives of many people within the Michif communities in the area, and therefore is very effective to the purpose |

| Levels of use/participation | The booklet is available for free download on heritage Saskatchewans website, this makes it widely accessible to anyone that comes across it |

| Levels of interactions, communication, transaction and exchange – the relationship between people and activities and the establishment of critical mass (SEI, 18) | This project took a great deal of organization and involved many groups and individuals to work together. This includes the people who consented to submit stories and artwork, the groups that collected the work, the designers who put together the booklet, those who provided funding, and the publishers |

| Level of representation – how the ecomuseum is projected and discussed in the outside world (SEI, 18) | It is unclear how far this project has reached overall due to the website it is posted being public domain, anyone with open internet access could view it |

WORKS CITED

Websites

- Catherwood, Kristin.“PressReader.com – Connecting People through News.” Pressreader.com, PressReader, 2019.

- CBC Radio. “Western Museums Need to Return Stolen Artifacts to ‘Get on the Right Side of History,’ Says Art Historian.” CBC, 11 Nov. 2021.

- Coal in Coronach. “Coal in Coronach – Heritage Saskatchewan.” Heritagesask.ca, 2017.

- GlennSutter.com. “Glenn Sutter – About.” Glennsutter.com.

- Heritage Saskatchewan. “Coal in Coronach Full Community Version.” YouTube, 2021.

- Heritage Saskatchewan. “Ecomuseums – Heritage Saskatchewan.” Heritagesask.ca.

- Massey, Sandra. “Museums without Walls: Getting the Conversation Started on Ecomuseums.” www.saskculture.ca, 2014.

- Merriam-Webster. “Definition of in SITU.” Merriam-Webster.com, 2020.

- Métis Road Allowance Memories. “Métis Road Allowance Memories – Heritage Saskatchewan.” Heritagesask.ca, 2019.

- North Central Regina. “North Central Regina as an Urban Eco Museum.” Uregina.ca, 2014.

- Sutter, Glenn & Kincaid, Adela & Fletcher, Amber. “Highlights and Future Directions for Ecomuseum Development in Saskatchewan.” Prairie Forum, vol. 40, 2019, pp. 72-83.

- Sutter, Glenn C., Tobias Sperlich, Douglas Worts, René Rivard, and Lynne Teather. 2016. “Fostering Cultures of Sustainability through Community-Engaged Museums: The History and Re-Emergence of Ecomuseums in Canada and the USA” Sustainability, vol. 8, no. 12, p. 1310. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8121310

- UNESCO. “Safeguarding Communities’ Living Heritage | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.” www.unesco.org,.

- Val Marie. “About Val Marie.” Village of Val Marie & R.M.

Podcasts

Power, Kevin. “SaskScapes – the Ecomuseums of Saskatchewan.” Culture Days Saskatchewan, 26 Feb. 2015.

Pamphlets

- Heritage Saskatchewan, and Museums Association of Saskatchewan. Ecomuseum Concept a Saskatchewan Perspective on ‘Museums without Walls.’ 2015

- L. Massey, S. Living Heritage & Quality of Life: Reframing Heritage Activity in Saskatchewan. 2012.

- Saskatchewan Ecomuseums Initiative (SEI). Newly Forming Ecomuseums Development Framework. 2016.

Banner image: “Val Marie School Grade 10 and 11 classes and Maurice Lemire at the Val Marie Heritage Elevator March 14, 2018.” Photo: Kristin Catherwood, Heritage Saskatchewan.