A “Sustainable” Place to Grow? Intensification and Conservation in the St. Lawrence Neighbourhood HCD, Toronto, Ontario

Case study prepared by Greg MacPherson, Carleton University

Keywords: Intensification, Urban Planning, Toronto, Sustainability, Appeals

Lessons Learned

A case study examining the St. Lawrence Neighbourhood Heritage Conservation District, the St. Lawrence Neighbourhood Heritage Conservation District Plan (SLNHCDP), and the appeal of the SLNHCDP to Ontario’s land use planning tribunal offers several key lessons applicable locally and globally. Generally, the case study highlights the implicit tensions which influence heritage conservation decision-making processes, contributes to an understanding of the challenges in integrating urban planning and heritage conservation practices for sustainable development, and reiterates the necessity of consultation and consensus-building in heritage conservation policymaking.

An evaluation of the SLNHCDP appeal reveals that environmental and economic sustainability factors implicitly influence conservation decision-making, given their entrenchment within broader policy frameworks regulating urban planning in Ontario. Environmental and economic sustainability influence conservation decision-making through the prioritization of intensification in policy statements, framed as a key contributor to environmental sustainability through the efficient uses of resources and contributing to the neoliberalization of land through speculative purchasing and development made viable by increased densification potentials. Regardless of if conservation decisions specifically address these factors, this is the context that most land-related decisions exist within and must contend with. The case study also highlights the necessity of consensus building and consultation, as concerns from the local development community and subsequent appeals of the SLNHCDP resulted in a plan developed over multiple years altered significantly. Therefore, in contexts where appeal to appellant bodies is a possibility, broad approval of heritage conservation plans should be prioritized where possible.

A presentation was delivered on November 25, 2021, providing an introductory summary of the St. Lawrence Neighbourhood Heritage Conservation District Plan and the related tribunal appeal. The presentation included a description, timeline and analysis of the sustainable aspects of the case study subject.

Description

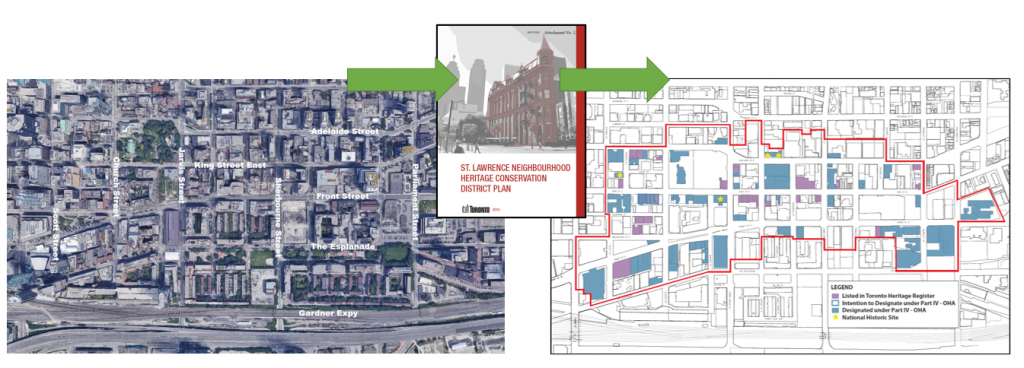

Located in downtown Toronto’s south-east and centred on the iconic St. Lawrence Market, a historic commercial hub and longstanding tourist destination, the St. Lawrence neighbourhood is an area significant to the historical and contemporary functioning of the City of Toronto (Dickau et al.; City of Toronto, St. Lawrence Neighbourhood Heritage Conservation District Plan). In December 2015, the City of Toronto designated the majority of the St. Lawrence neighbourhood under Part V of the Ontario Heritage Act, the governing legislation for heritage conservation in the Province of Ontario, to establish the St. Lawrence Neighbourhood Heritage Conservation District and implement its associated management plan, the St. Lawrence Neighbourhood Heritage Conservation District Plan (SLNHCDP) (City of Toronto, St. Lawrence Neighbourhood Heritage Conservation District Plan). This plan was subsequently appealed to Ontario’s urban planning appeal tribunal, known in 2015 as the Ontario Municipal Board, by a consortium of area property owners (Vincent). The SLNHCDP and its appeal are of particular interest as a sustainable heritage case study because they highlight the ongoing tensions between the adjacent practices of urban planning and heritage conservation, particularly concerning urban intensification policies. The remainder of this section defines three concepts critical to understanding and assessing the St. Lawrence Neighbourhood Heritage Conservation District and the appeal of the SLNHDCP.

Heritage Conservation Districts: In Ontario, a heritage conservation district refers to an area of a municipality designated under Part V of the Ontario Heritage Act (OHA). Designation under Part V of the OHA “enables the council of a municipality to manage and guide future change in the district through the adoption of a district plan with policies and guidelines for conservation, protection and enhancement of the area’s character or appearance” (Government of Ontario, Ontario Heritage Toolkit: Heritage Conservation Districts (Draft) 5). HCDs have many similarities with UNESCO’s Recommendations for the Historic Urban Landscape, with both seeking to integrate conservation into existing frameworks for development and conserve heritage values in a landscape setting (Rey-Pérez and Pereira Roders).

Urban Intensification: Urban Intensification is defined as “the densification of population and built form in cities” (Bunce 6). The Provincial Policy Statement and A Place to Grow: Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe, two policy documents which municipal planning strategies are required to conform with,both establish intensification as a goal for existing urban areas in the Greater Toronto Area (Government of Ontario, Provincial Policy Statement, 2020; Government of Ontario, A Place to Grow: Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe). Generally, intensification is framed as a contributor to sustainable development, despite a lack of consensus regarding its actual impact (Bunce 6).

Ontario Land Tribunal and Planning Appeals: Land use planning and heritage conservation decisions made by municipalities are subject to appeal to the Ontario Land Tribunal, an independent appellant board established under the Ontario Land Tribunal Act (Ontario Land Tribunal). Prior to 2021, the Ontario Land Tribunal was known as the Ontario Municipal Board until 2017, and the Local Planning Appeal Tribunal from 2017 to 2021 (Ontario Land Tribunal).

Timeline

The selected case study site represents a living historic neighbourhood in Toronto, a designated heritage conservation district with associated management policies, and a related legal dispute simultaneously. The following timeline highlights key dates in the establishment of the St. Lawrence Neighbourhood HCD, the creation of the SLNHCDP, and the appeal of the SLNHCDP.

Development of SLNHCDP (City of Toronto)

| Date | Action |

| July 2005 | St. Lawrence Neighbourhood identified by City of Toronto as potential HCD |

| September 2009 | St. Lawrence Neighbourhood Potential Study Area expanded |

| June 2013 | Formal HCD study commences |

| May 2014 | Study concludes and is endorsed by Toronto Preservation Board |

| September 2014 | HCD Plan development begins |

| October 2015 | City heritage staff recommend approval of HCD Plan |

| November 2015 | HCD Plan endorsed by TPB |

| December 2015 | City Council Adopts HCD Plan |

| January 2016 | Appeals of HCD Plan submitted to OMB (later LPAT, now OLT) |

| November 12, 2019 | LPAT Hearing Commences |

| July 2020 | LPAT decision released, HCD Plan and Boundary altered |

| November 2021 | Revised plan approved by Ontario Land Tribunal (not yet publicly available |

Stakeholders

The stakeholders identified below represent those relevant to the development and implementation of the St. Lawrence Neighbourhood Heritage Conservation District and SLNHCDP, in addition to those involved in its appeal. Stakeholder consultation in support of the heritage conservation district study was undertaken throughout 2014 and 2015 by the City of Toronto and the HCD consultant team, consisting of FGDMA Architects, Archaeological Services Inc., and Bousfields Inc (City of Toronto, St. Lawrence Neighbourhood Heritage Conservation District Plan). Consultation included focus group meetings with members of the St. Lawrence Neighbourhood Association Development Sub-Committee, public community consultation meetings, and individual meetings with local property owners (City of Toronto, St. Lawrence Neighbourhood Heritage Conservation District Plan 18). Indigenous groups and institutions were not identified as key stakeholders in the HCD study process and accordingly did not participate in specific engagement sessions with the City of Toronto.

Stakeholders (City of Toronto, Vincent)

| Government | City of Toronto Province of Ontario Toronto Preservation Board |

| Extra-Governmental | Ontario Land Tribunal (Local Planning Appeal Tribunal/LPAT) |

| Community | St. Lawrence Neighbourhood Association (SLNA) St. Lawrence Neighbourhood Residents St. Lawrence Market Neighbourhood BIA St. Lawrence Neighbourhood Market Business Owners |

| Institutional | Toronto Public Library George Brown College Canadian Opera Company Toronto Public School Board |

| Development Industry | Allied Properties REIT: York Heritage PropertiesBILDGWL Realty AdvisorsLamb Bahaus Inc. First Gulf King Street Premium Properties Ltd. York London Holdings |

| Consultants | FGDMA Architects Archaeological Services Inc Bousfields Inc |

Heritage

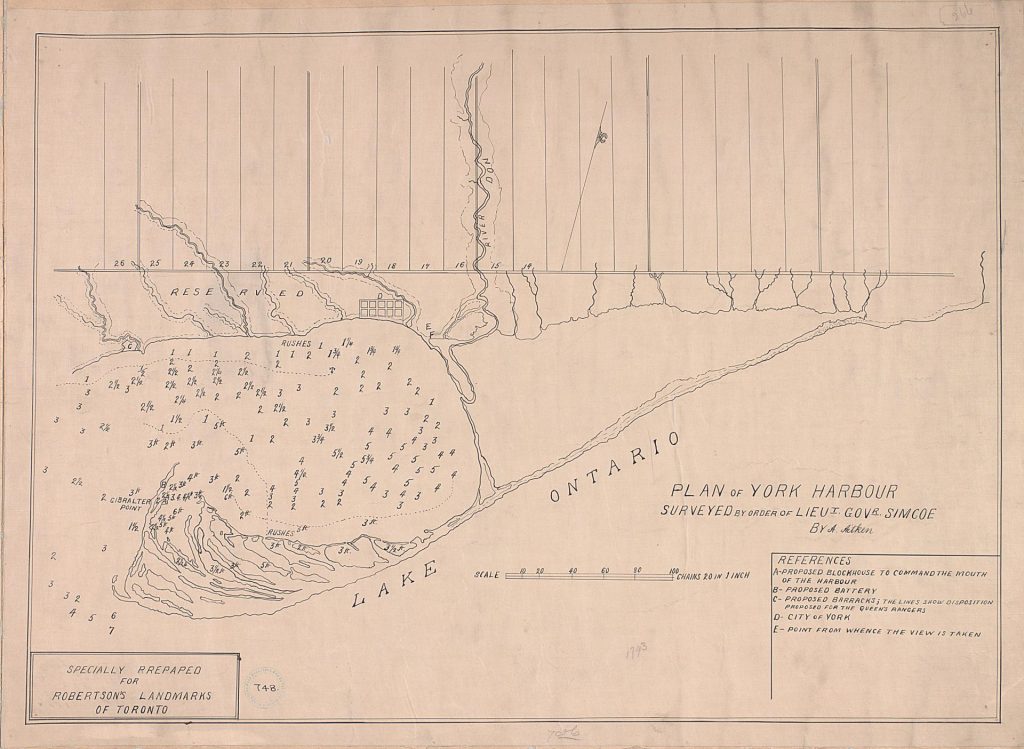

Natural Heritage: The dense urban setting of the St. Lawrence Neighbourhood Heritage Conservation District results in few natural heritage resources existing within its boundaries, except for mature street trees throughout the district and limited vegetation within some urban parks, including Berczy Park and St. James Park. However, the evolution of Toronto’s shoreline along Lake Ontario – and accordingly the growth and development of downtown Toronto from the 18th century to the present day – is reflected in the street pattern and orientation of the St. Lawrence Neighbourhood towards the waterfront. Front Street, the spine of the St. Lawrence Neighbourhood HCD, was built along the former shoreline of Lake Ontario (Waterfront Toronto). Over approximately 100 years, beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, the shoreline was infilled to support continued industrial growth in manufacturing, enabled by the significant shipping industry on the Great Lakes, creating the lands south of Front Street (Desfor and Laidley; Waterfront Toronto). Commemoration of the original shoreline exists in piecemeal form throughout the surrounding area, but a cohesive strategy is currently in development, separate from the St Lawrence Neighbourhood HCD (St. Lawrence Neighbourhood Association). While not referenced explicitly in any related documentation, the future commemoration of the original shoreline presents an opportunity to collaborate and engage with Indigenous communities and institutions, especially in light of ongoing claims to title over Lake Ontario (Government of Ontario, ‘Current Land Claims’).

Cultural Heritage: The St. Lawrence Neighbourhood HCD designates the subject area under Part V of the Ontario Heritage Act. The SLNHCDP, the associated management plan enabled by the Part V designation and required under the Ontario Heritage Act, summarizes the cultural heritage value and interest of the subject area as follows:

The cultural heritage value and interest of the St. Lawrence Neighbourhood HCD is based on three factors. The District has historical value as the original footprint of the town of York, which was the seat of government for Upper Canada and which evolved into the City of Toronto and capital of Ontario. Secondly, the District has its own distinctive physical character, which includes its concentration of 19th century buildings. Thirdly, the District has contextual, social and community significance by virtue of its numerous institutions and landmarks, including the St. Lawrence Market and Hall, St. James Cathedral and its numerous theatres. (City of Toronto, St. Lawrence Neighbourhood Heritage Conservation District Plan 26)

In addition to the designation of properties as part of the St. Lawrence Neighbourhood HCD, numerous buildings within its boundaries are designated as individual heritage properties under Part IV of the Ontario Heritage Act, including the Gooderham Building at the intersection of Wellington, Front, and Church Street. Properties designated individually have a designation by-law registered on the property’s title, which establishes specific physical attributes to be conserved and summarizes the individual significance of the property.

Sustainability

Environmental Sustainability: The SLNHCDP and its appeal make limited direct reference to concepts of environmental sustainability. Section 6.9 of the original plan encourages new development and alterations to non-contributing properties in the district to meet or exceed Tier 2 of the Toronto Green Standard, a recently approved set of policies that regulate the environmental performance of new development (City of Toronto, Toronto Green Standard (TGS) Version 4 Adopted by Toronto City Council; City of Toronto, St. Lawrence Neighbourhood Heritage Conservation District Plan 138). Despite emerging trends relating concepts such as the circular economy to heritage conservation through retrofits, adaptive reuse and deconstruction, similar policies do not apply to contributing buildings within the HCD (Foster; Huuhka and Vestergaard).

Environmental sustainability is considered implicitly through the position of the SLNHCDP and its appeal within the intensification-focused planning policy framework in Ontario. In its final order, the Local Planning Appeal Tribunal removed all policies within the SLNHCDP that prescribe mandatory setbacks and the application of an angular plane to new development, reducing policies related to compatibility between new development and contributing buildings to guidelines, therefore enabling the achievement of greater densities within the HCD. This outcome resembles the general approach recommended by Skrede and Berg, who suggests that sustainable development via densification should be undertaken with an explicit cultural component influencing decision-making, such as the SLNHCDP (Skrede and Berg). In theory, this revised framework will result in more environmentally sustainable urban development as greater density can be achieved using existing resources; however, the pursuit and prioritization in policy of a property’s most intense developed form use can also undermine community values and priorities such as those identified through consultation during the creation of the SLNHCDP (Leffers and Ballamingie). :

Economic Sustainability: The SLNHCDP does not explicitly address economic sustainability. Urban intensification, a key issue in the subject case study, has been framed as a planning discourse that can hide the economic interests of developers behind sustainability goals (Kern; Rosol). Given the neo-liberalization of the real estate market, policies supporting intensification have further exacerbated land value and the potential for gentrification in existing urban centres (Bunce). Therefore, by imposing policies that seek to regulate urban intensification within the St. Lawrence Market HCD, the SLNHCDSP can impact the economic sustainability of the City of Toronto and private property owners within it.

Measurement

This case study simultaneously examines related components nested within a common geographic area: the St. Lawrence Neighbourhood Heritage Conservation District Plan and the appeal of the approved heritage conservation district plan to the former Local Planning Appeal Tribunal. As such, measurement must relate to both the contents of the plan itself and the specifics of the appeal and subsequent order. The following review applies three different methodological approaches – two focused on evaluating social sustainability in historic urban environments, the other intended to assess the multi-faceted elements that makeup debates in heritage conservation – to provide a holistic assessment of the case study subject. The review also suggests measures for assessing the environmental sustainability of future development projects located within the jurisdiction of the heritage conservation district plan.

Landorf’s Evaluation of Social Sustainability: The specific impacts and contributions of the SLNHCDP to social sustainability can be assessed using Landorf’s “Social sustainability evaluation criteria for historic urban environments” (Landorf 472). Landorf frames social sustainability as a three-dimensional framework, derived from a review of existing literature on social sustainability and sustainable development, consisting of social equity, social coherence, and basic needs (Landorf 468–69). Using these dimensions, Landorf proposes a flexible framework for heritage assessment, capable of producing “indicators that allow [for] a consistent appraisal of sustainable development objectives within any historic urban environment while providing a basis for the assessment of any new development within a historic area” (Landorf 471). The following chart considers the social sustainability of the SLNHCDP following the amendments ordered by the LPAT.

| Dimension | Characteristics | Localized Examples |

| Social Equity | Access to services, facilities, and opportunities | Creation of new housing units potentially increased |

| Level of institutional stability and flexibility | Municipal decision overturned by separate, non-local decision-making bodyConfidence in long term stability of heritage conservation decisions potentially eroded | |

| Social Coherence | Strength of networks, participation, identification and tolerance | Questions surrounding social coherence and sustainability not addressed explicitly |

| Level of empowerment and accountability | Community given limited role in LPAT appeal despite significant contributions to plan creation | |

| Basic Needs | Objective satisfaction of basic needs | Character of built environment positively impacted: greater potential for contextually sensitive design |

Rodwell’s Principles for Sustainable Heritage Conservation: In an early theorization of the relationship between heritage conservation and sustainable development, Dennis Rodwell suggests that sustainable heritage conservation relies on engagement and an extended sense of resource value (Rodwell). Building on Giovannoni’s theory of harmonious co-existence, Rodwell suggests that conservation and sustainable development can be compatible if they are creatively integrated into the development process, resource value is enhanced to consider existing material resources for their environmental benefits, and engagement is broadened to “shed [conservation’s] timidity” (Rodwell 67). Rodwell sets out multiple guiding principles for sustainable heritage conservation, intended to capture the range of factors that must be considered in a conservation project and contribute to sustainable, “bottom-up” conservation and planning processes (Rodwell 68). The following chart comments on the relationship between a selection of these principals and the SLNHDCP.

| Principle | Description (Rodwell) | Case Study |

| Participation | To secure ‘common ownership’ of a conservation- and sustainability-orientated vision and approach to our tangible and intangible heritage. | Participation was a priority in the creation of the HCD Plan, but more stakeholders could still be reached. Participant interests go largely unconsidered in tribunal setting. |

| Sustainability | To express concisely and convincingly the connections between the conservation of our built heritage and the wider national and international agendas of sustainability. | Heritage conservation in Ontario is tied directly to the planning process, therefore requiring conformity with broader sustainability goals even if they are not considered explicitly in conservation program. |

| Housing | To minimize destructive interventions in the built and social fabric and to maximize the potential of historic city areas to function as sustainable communities. | Heritage conservation can contribute to the provision of housing units, or it can reduce a development’s potential size. Contextual development can help strike an appropriate balance. |

| Urban Planning | To provide the framework within which historic city areas can contribute to today’s society whilst retaining the integrity of their tangible and intangible heritage. | Urban planning and heritage conservation are adjacent frameworks and processes that must coordinate to achieve broader sustainability goals. |

Mualam and Alterman’s Framework for Evaluating Heritage Conservation Disputes: Mualam and Alterman propose a framework for identifying and assessing the multi-faceted dimensions of heritage conservation disputes, arguing that despite assumptions regarding the dominance of architectural or aesthetic factors in conservation decision making, “[b]uilt-heritage [conservation] invokes conflicts which are not limited to built form” (Mualam and Alterman 304). Using a dispute settled at Israel’s National Appeal Tribunal – one of few appellant bodies comparable to the Ontario Land Tribunal – as an example, Mualam and Alterman frame the appeal of a large-scale heritage conservation district plan by multiple property owners along a pro-preservation and anti-preservation binary organized around five factors: architectural, planning, social, economic, and property (Mualam and Alterman 305; Mualam). This framing allows for factors less explicitly prevalent in typical heritage conservation decision-making processes – such as economic factors, which the Ontario Heritage Act officially does not consider – to be assessed alongside others. Notably, this framework omits the inclusion of environmental factors despite including other pillars of sustainability, likely a symptom of the still underdeveloped relationship between conservation, planning, and sustainable development (Avrami). As such, the framework has been adapted to consider environmental factors. The following chart evaluates the SLNHCDP appeal within Mualam and Alterman’s framework.

| Dimension of Conflict | Pro-preservation | Anti-preservation |

| Architectural | Municipal support for strict regulation of built-form through standards within HCD | Appellant position that prescribed standards are redundant, not correctly implemented |

| Planning | Municipal position that HCD plan is legally empowered to contradict Planning Act policy | Appellant position that HCD Plan cannot in any form conflict with Official Plan |

| Social | Municipal position that the provision of new housing units via intensification must conform to standards in HCD Plan | Appellant position that provision of new housing units via intensification should be based on iterative contextual development |

| Economic / Property | Limited consideration by municipality | Implicit – appeal of HCD Plan initiated primarily by development corporations, likely influenced by economic interests in developing lands in HCD |

| Environmental* | Supports intensification where appropriate using HCD policies | Supports intensification where appropriate using iterative contextual development |

Works Cited

Books/Book Chapters/Journal Articles

- Avrami, Erica. ‘Making Historic Preservation Sustainable’. Journal of the American Planning Association, vol. 82, no. 2, Apr. 2016, pp. 104–12. DOI.org (Crossref), doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2015.1126196.

- Bunce, Susannah. Sustainability Policy, Planning and Gentrification in Cities. Routledge, 2018.

- Desfor, Gene, and Jennefer Laidley. ‘Introduction’. Reshaping Toronto’s Waterfront, University of Toronto Press, 2011.

- Dickau, Joel, et al. ‘If You Wanted Garlic, You Had to Go to Kensington: Culinary Infrastructure and Immigrant Entrepreneurship in Toronto’s Food Markets before Official Multiculturalism’. Food, Culture & Society, vol. 24, no. 1, Jan. 2021, pp. 31–48. DOI.org (Crossref), doi.org/10.1080/15528014.2020.1860375.

- Foster, Gillian. ‘Circular Economy Strategies for Adaptive Reuse of Cultural Heritage Buildings to Reduce Environmental Impacts’. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, vol. 152, Jan. 2020, p. 104507. ScienceDirect, doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104507.

- Huuhka, Satu, and Inge Vestergaard. ‘Building Conservation and the Circular Economy: A Theoretical Consideration’. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development, vol. 10, no. 1, Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2020, pp. 29–40.

- Kern, Leslie. ‘Reshaping the Boundaries of Public and Private Life: Gender, Condominium Development, and the Neoliberalization of Urban Living’. Urban Geography, vol. 28, no. 7, Routledge, Oct. 2007, pp. 657–81. Taylor and Francis+NEJM, doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.28.7.657.

- Landorf, Chris. ‘Evaluating Social Sustainability in Historic Urban Environments’. International Journal of Heritage Studies, vol. 17, no. 5, Routledge, Sept. 2011, pp. 463–77. Taylor and Francis+NEJM, doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2011.563788.

- Leffers, Donald, and Patricia Ballamingie. ‘Governmentality, Environmental Subjectivity, and Urban Intensification’. Local Environment, vol. 18, no. 2, Routledge, Feb. 2013, pp. 134–51. Taylor and Francis+NEJM, doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2012.719016.

- Mualam, Nir. ‘Appeal Tribunals in Land Use Planning: Look-Alikes or Different Species? A Comparative Analysis of Oregon, England and Israel’. The Urban Lawyer, vol. 46, no. 1, 2014, pp. 64-.

- Mualam, Nir, and Rachelle Alterman. ‘Architecture Is Not Everything: A Multi-Faceted Conceptual Framework for Evaluating Heritage Protection Policies and Disputes’. International Journal of Cultural Policy, vol. 26, no. 3, Routledge, Apr. 2020, pp. 291–311. Taylor and Francis+NEJM, doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2018.1518978.

- Rey-Pérez, Julia, and Ana Pereira Roders. ‘Historic Urban Landscape: A Systematic Review, Eight Years after the Adoption of the HUL Approach’. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development, vol. 10, no. 3, Jan. 2020, pp. 233–58. doi.org/10.1108/JCHMSD-05-2018-0036.

- Rodwell, Dennis. ‘Sustainability and the Holistic Approach to the Conservation of Historic Cities’. Journal of Architectural Conservation, vol. 9, no. 1, Routledge, Jan. 2003, pp. 58–73. doi.org/10.1080/13556207.2003.10785335.

- Rosol, Marit. ‘Vancouver’s “EcoDensity” Planning Initiative: A Struggle over Hegemony?’ Urban Studies, vol. 50, no. 11, SAGE Publications Ltd, Aug. 2013, pp. 2238–2255. doi.org/10.1177/0042098013478233.

- Skrede, Joar, and Sveinung Krokann Berg. ‘Cultural Heritage and Sustainable Development: The Case of Urban Densification’. The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice, vol. 10, no. 1, Jan. 2019, pp. 83–102. doi.org/10.1080/17567505.2019.1558027.

Policies and Reports

- City of Toronto. St. Lawrence Neighbourhood Heritage Conservation District Plan. 2015.

- —. Toronto Green Standard (TGS) Version 4 Adopted by Toronto City Council. City of Toronto, 30 July 2021.

- Government of Ontario. A Place to Grow: Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe. Ontario Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing, 1 May 2020.

- —. ‘Current Land Claims’. Ontario.Ca, Dec. 2021.

- —. Ontario Heritage Toolkit: Heritage Conservation Districts (Draft). 2021.

- —. Provincial Policy Statement, 2020. 28 Feb. 2020.

Websites

- Ontario Land Tribunal. ‘About the OLT’. Ontario Land Tribunal.

- Ontario Land Tribunal. ‘About the OLT’s Planning Jurisdiction’. Ontario Land Tribunal.

- St. Lawrence Neighbourhood Association. ‘Original Shoreline Commemoration’. SLNA – St. Lawrence Neighbourhood Association.

- Vincent, Sharyn. Allied Properties REIT v. Toronto (City). 27 July 2020.

- Waterfront Toronto. ‘History & Heritage’. Waterfront Toronto.

Banner image: TBD