Tr’ondëk-Klondike: Evaluating a Nominated World Heritage Site

Case Study prepared by Jonas Vasseur, Carleton University

Keywords: Indigeneity, cultural tourism, ecological integrity, economic sustainability, Yukon, Gold Rush

Lessons Learned

The proposed Tr’ondëk-Klondike world heritage site represents a meeting of Indigenous peoples and newcomers, similar to meetings that took place all over the world in the larger history of colonization. The site and its nomination are a case study of the continuing process of colonization, evident first in that the first nomination area was shrunk to not include mining areas rather than improving the protections on the area. And despite a stated focus on collaboration, management plans for the component sites and a separate process with similar stakeholders show a significant difference in priorities. These problems emphasize the importance of control of Indigenous culture resting in their own communities and in prioritizing actual and committed collaboration in heritage and sustainability projects.

Presentation

Description

The proposed Tr’ondëk-Klondike world heritage site represents a meeting of Indigenous peoples and newcomers, similar to meetings that took place all over the world in the larger history of colonization. Like many of these meeting spots over the world, overtures from the local Indigenous populations were largely ignored as newcomers assumed that the “exotic” people who already inhabited the land would transform into something more recognizable.

As Neufeld describes, Chief Issac of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in made efforts to reach out to newcomers that were largely ignored, including invitations to Christmas gatherings (116). Instead, as at many other sites of contact the newcomers sought unity through a racial Anglo-Saxon identity, represented by the governing institutions of Britain and the United States. In order to establish and maintain clear physical and social boundaries, the newcomers’ Indigenous neighbours were moved several times (Neufeld 120).

The previous incarnation of this proposed world heritage site once focused much more on the narrow point of time of the Klondike Gold Rush (covered more below under Heritage). Over the course of more than a century, the narrative of an untouched land of mineral resources was developed through a national effort to deny Indigenous peoples their past, present, and future (Neufeld 128) and we can still see efforts to do this today. The Klondike region is more than just the Gold Rush, and more than just a moment in time.

The Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in hold a connection to the area that stretches back far into the past, at least 8000 years (as the lowest estimate) in the community of Moosehide (Green). Notably, the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in hold a strong history of adapting to extreme circumstances as they came—including in weather extremes and food scarcity—and survived as a people and culture in spite of colonial efforts to the contrary (Parks Canada 6). The current incarnation of the site nomination better reflects influences from the Trondëk Hwëch’in.

Since signing their 1998 self-government agreement with Canada in 1998, the Trondëk Hwëch’in First Nation have been able to better express the desire to present their own cultural narrative of the Trondëk-Klondike region and have articulated worries about a lack of representation at national historic sites in the Klondike region (Neufeld 115).

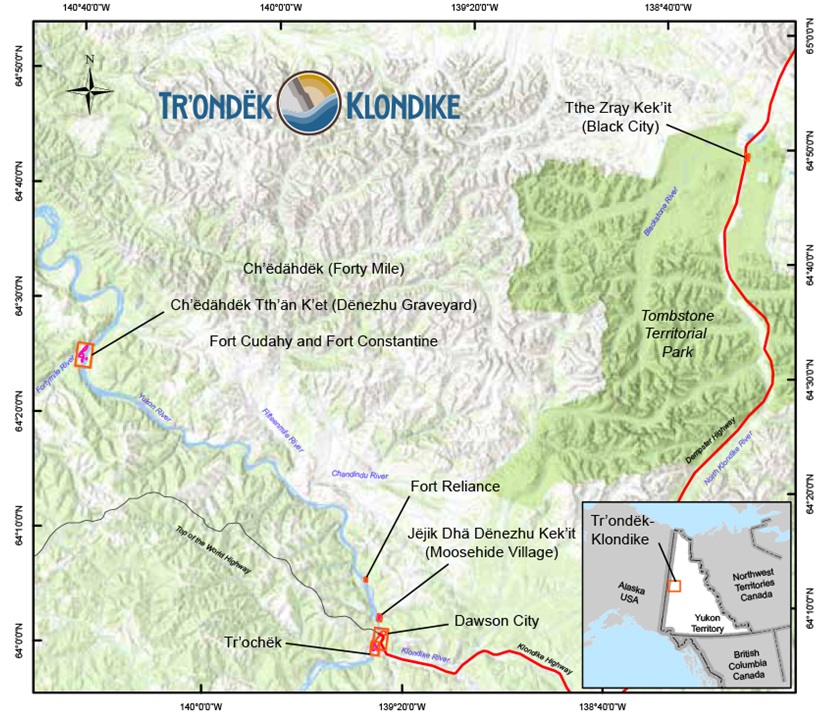

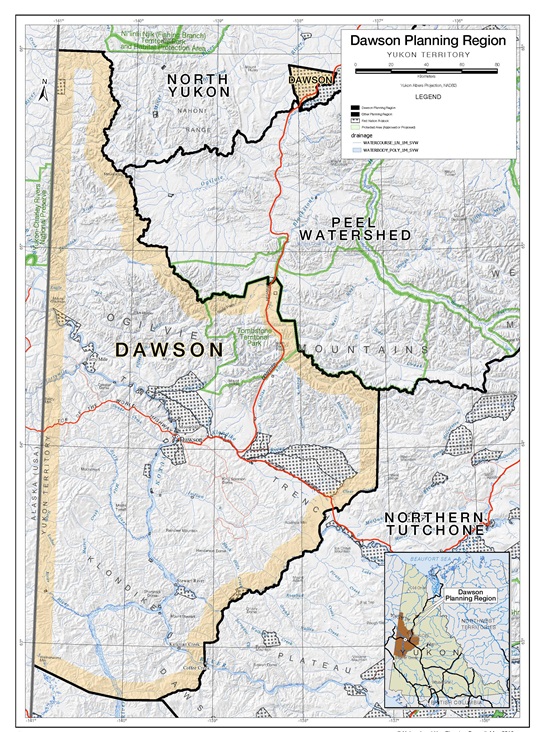

The nominated world heritage site is a serial site made up of 8 component sites that together tell the story of the experiences of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation people and responses to colonialism between 1874-1908.

All 8 of those sites, except Dawson City, are on Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in settlement lands or are on co-managed lands. Those sites are “Fort Reliance; Ch’ëdähdëk (Forty Mile); Ch’ëdähdëk Tth’än K’et (Dënezhu Graveyard); Fort Cudahy and Fort Constantine; Tr’ochëk; Dawson City; Jëjik Dhä Dënezhu Kek’it (Moosehide Village); and Tthe Zra¸y Kek’it (Black City)” (“Trondëk-Klondike World Heritage Status”).

In order to spend more time focusing on the site as a whole these individual component sites will largely not be referred to individually, but readers are encouraged to refer to the nomination website for further information, as referenced in the works cited section.

Timeline

As with many sites that highlight Indigenous heritage, one of the difficulties in describing the sites is formulating a timeline that does not erase Indigenous voices and histories. As described above, the Moosehide settlement shows evidence of habitation for at least 8000 years.

Forty Mile shows significant evidence of occupation and use for at least 2300 years, and other archaeological evidence and oral histories describe habitation in the Yukon long before those dates (Campbell et al. 2). Both in order to limit the scope of this analysis and to better reflect the time period around initial Contact that these sites represent, this section will mostly focus on the period of contact (1874-1908) and the significant dates after that impact the management of the sites.

• 8000+ years ago: Indigenous habitation of area

• 1874: Period of major contact begins

In virtually every meeting point with new, Indigenous cultures, European settlers tended to view Indigenous peoples as “incomplete,” or almost as branched relics of their own past. The perspective that there was one form of human development and that they were the leaders in it informed the meeting in the area that would come to be known as Trondëk-Klondike (Neufeld 113).

Gold was originally mined near the Forty Mile community, but there was not enough to warrant a widespread gold rush as would be seen soon. However, with the discovery of gold on Bonanza Creek 1896, the Klondike Gold Rush would soon be in full swing.

• 1896: Discovery of gold on Bonanza Creek

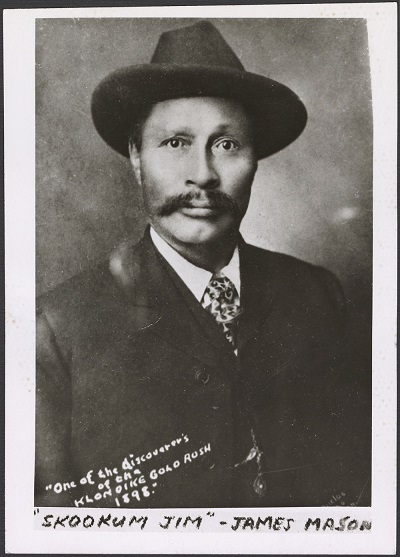

Unfortunately, even though the Yukon Commissioner recognized Skookum Jim Mason (Keish), a Tagish First Nation man, as the discoverer of gold initially, this would not make it into official narratives. To really sell the pioneer narrative white men were needed as founders of this new gold rush, and so the American George Carmacks and Canadian Robert Henderson were given joint attribution for the find (Neufeld 123).

• 1911: All-time high of Klondike gold bed production

• 1948: Alaska Highway opens to the public

• 1953: Yukon’s capital city shifts to Whitehorse

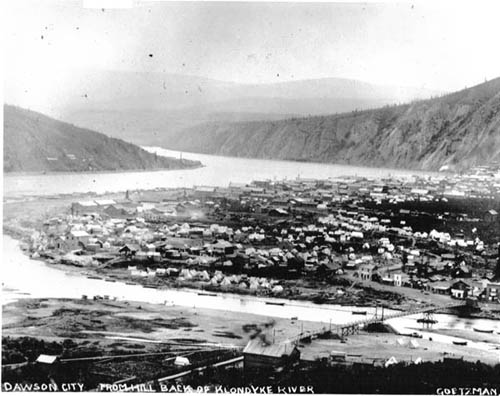

In Dawson City, the town that sprung up to support the Klondike Gold Rush, major mining operations began to take place over most of the Klondike gold beds, with an all-time high in gold production in 1911 that would be followed by significant declines (City of Dawson and Trondëk Hwëch’in 4).

The population of the Yukon continued to decline, and by the time the Alaska Highway connected the territory to the south expansive changes were already felt in the ways that people made a living, with informal cash economy opportunities almost disappearing (Neufeld 127).

• 1988: Umbrella Final Agreement first agreed upon

• 2004: “The Klondike” added to Canada’s tentative list for world heritage sites

The overall “umbrella” agreement of the Yukon Land Claims package was first agreed upon in 1988, and finalized in 1990. It provided the space and background for general agreements between the Canadian federal government, the Yukon territorial government, and the 14 Yukon First Nations (“Umbrella Final Agreement”).

In 2004 the Government of Canada released its second tentative list for world heritage sites, and the Klondike was included as representing the adaptation and innovation of First Nations people and as an exceptional example of a mining landscape (Neufeld 113).

• 2018: Initial nomination bid withdrawn

• 2021: Second nomination bid submitted

• 2022: Expected year of nomination decision

The original nomination bid was withdrawn in 2018, following critique from the UNESCO advisory body that the site was difficult to understand and that designating active mining sites was not within the scope of the list. In addition to this, placer miners in the area worried that a designation might bring about new restrictions (“Dawon City’s bid on hold”).

3 years later, a local committee based in Dawson City decided to try again, this time with a smaller area and a tighter focus for the nomination bid. The current nomination package focuses on the experiences of colonialism felt by First Nations, and it is expected that a decision to inscribe, delay the decision, suggest revisions, or reject will be made sometime in 2022 (“Yukon World Heritage bid shifts”).

Stakeholders

Although many other people and groups do not fit within them, to offer greater depth in this analysis, this case study focused on three main categories:

- Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation

- Territorial and municipal governments, with this analysis largely focusing on their economic concerns).

- Evironmentalists, who share much overlap with the First Nation.

The Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in and other Yukon First Nations were willing to enter Canada, but only on their own terms. They made sure that this involvement would not be simply in terms of tolerance, but rather on inclusion that acknowledged their power, knowledge, interests, and agency (Neufeld 129).

The Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in accepted the responsibility to lead the community consultations for the Tr’ondëk-Klondike site nomination, and fostered a nomination which promised to equitably tell the story of the region. Other organizations submitted feedback served in an advisory capacity, ranging from tourist organizations, the Chamber of Commerce, museums, mining associations, the territorial government, and Parks Canada, among others (“Tr’ondëk-Klondike World Heritage Status”).

As recognized in the Dawson City Integrated Community Sustainability Plan, a document which involves one of the sites of the nomination area and included many of the same stakeholders, planning decisions cannot be considered in isolation from the wider community (City of Dawson and Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in iv).

In most of the policy documents cited in this post the stakeholders were required to work together and seek compromise when goals differed. This came out most when considering two of the largest industries in the Yukon, the tourism sector and the mining industry. For example, the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in are not opposed to mining on principle, but want to ensure that it is carried out with proper consultation and reduced impacts on the land and water. The biggest questions that typically emerge around mining in the Yukon are what job opportunities will look like and what environmental impacts the mine will bring (Green).

Gold has been a large part of the Yukon economy since the days of the gold rush. Large-scale gold mining ceased in the 1960s, but placer-mining and mining for other minerals continues to be important to the Yukon’s economy (City of Dawson and Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in 4). Unfortunately, as will be explored further in the measurement portion of this post, the relationship between mining and Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in interests is not well-explored.

In southern Canada reserves were created to remove Indigenous peoples from land desired for settlement and agriculture, but in the Yukon where contact occurred later and large-scale settlement was not desired, Indigenous peoples were moved from traditional territories to make room for mining. Most of the areas inhabited by the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in were chosen as strategic sites for subsistence living, and so many of these moves prevented subsistence activities that had been occurring for centuries (Green).

As governments over the world attempt to address the socio-economic disadvantages experienced by Indigenous peoples, tourism has been advocated as a social intervention that may serve as a development force for host communities (Ruhanen and Whitford 179). Unfortunately, in too many cases the focus has been on the needs of non-Indigenous peoples, forgetting the very people those tourism initiatives were claimed to champion and setting the locus of control outside Indigenous nations (Ruhanen and Whitford 181).

There is a lot at stake in negotiating the relationship between tourism and Indigeneity in the Tr’ondëk-Klondike region, with impacts to be felt in the economy, on the land, and in Indigenous culture and life. The historic sites across the Yukon and Alaska relating to the Klondike Gold Rush host roughly 300,000 tourists annually, and continue to host series of films and television productions (Neufeld 114).

Many of the concerns of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in are related to the environment that their traditional territory rests in. The effects of climate change may be the biggest threat currently facing our planet, and have proven to be exacerbated in the north significantly. Fuel and energy shortages and crises, increasing globalization and commercialization, environmental degradation, and increasing resource consumption are all concerns that the Yukon faces (City of Dawson and Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in 6-9).

Recent policies such as the Dawson Regional Planning Commission (2019) hold long-term sustainability as a constant inspiration, and at the paper-level there is largely an understanding of the fact that economic sustainability and continued access to resources will require a sustainable environment (“Dawson Regional Planning Commission”).

Heritage

Indigenous heritage: As the current nomination focuses on the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in experience of colonization, it only seems fair that the major heritage values focused on will be those relating to them. As heritage is rooted in the landscape for the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in, their heritage is kept alive when they are able to hunt, fish, and harvest (“Dawso Regional Planning Commission”). As such, natural and cultural heritage values are being considered in tandem.

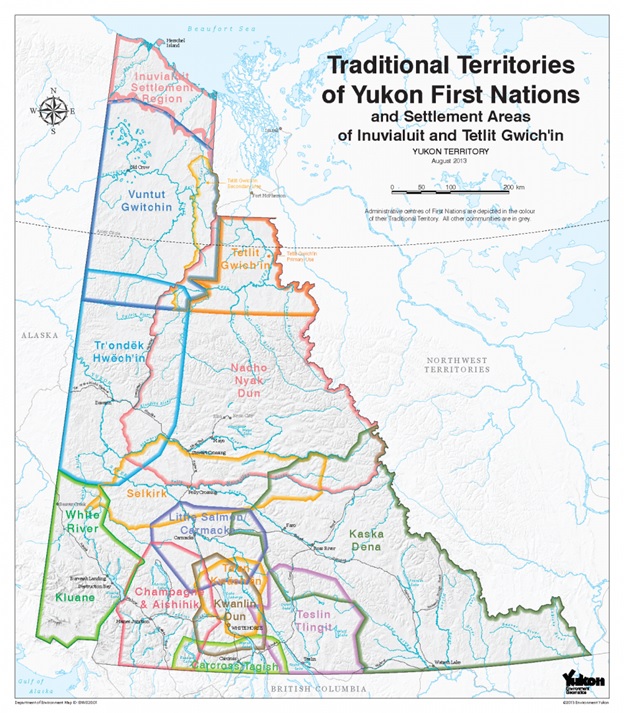

The Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in government represents approximately 1000 citizens, and exercise governance over approximately 2600 km2 of settlement lands. In addition, they hold hunting and other subsistence rights over more than 64,000 km2 of land that makes up their traditional territory (Roburn and TH Heritage Dep’t 440).

The First Nation’s central point of habitation is located in present-day Dawson City, and the nation’s name is evocative of the region, roughly translating to “the people who lived at the mouth of the Klondike (“Tr’ondëk-Klondike World Heritage Status”).

- Tr’o: hammer rock used to drive salmon weir stakes into the mouth of the river

- Ndëk: “river”

- Hwëch’in: “the people”

Water is immensely important to Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in people, both in terms of place and culture. Yukon First Nations describe the need to respect water and consider its place as a living entity with qualities of agency, describing water as not just enabling human life but as alive itself (Wilson et al. 3). These waters were not respected by newcomers, with miners originally arguing that the creation of new ponds and streams through intense mining was creating new habitats for animals, despite clear evidence in the present and centuries of Indigenous knowledge that ran contrary to this argument (Green).

Only through intense negotiation were the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in able to take back co-governance of all the lands and waters in the Yukon, retaining rights and title to less than 10% of their traditional territory in exchange for a partnered governance with the Yukon Government over their lands and waters (Wilson et al. 5).

Both the original and current nomination packages were located within the traditional territory of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in, and as discussed prior, the original nomination included active mining sites, which concerned UNESCO World Heritage about the future management of change within an industrial landscape (“Dawson City’s bid put on hold”).

The original area could have been maintained if the focus had been on the Indigenous people whose traditional territory the site rests on. Yet this area still holds memories of the original ideologies of the original newcomer miners, that nature was meant to be assessed, controlled, used, and valued commercially (Green).

For thousands of years the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in lived in close connection with the land, organizing their society around the animals and natural resources needed to thrive. Specifically at the component sites of Tr’ondëk-Klondike, the increasing impacts of colonialism over the course of a rapid three decades can be observed. Due to the boom-and-bust nature of gold rushes, these component sites were largely built rapidly and diminished in size nearly as rapidly, and these component sites have since been conserved and protected (“Tr’ondëk-Klondike World Heritage Status”).

Cultural heritage: An example of the cultural values found at these sites can be explored at Forty Mile, Fort Cudahy, and Fort Constantine (Campbell et al. 1).

- Early use as a site of caribou interception and as a spring grayling fish camp

- Where Hän culture was exposed to and changed by European influences

- First significant non-Indigenous settlement in the Yukon, a shift from furs to gold

Sustainability

One difficulty in addressing the sustainability of this region is that it exists within a much larger traditional territory within a much larger territory, and that territory is impacted by what is going on in the world at large.

An example of this in the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in’s traditional territory is the dramatically fewer numbers of Chinook salmon swimming into the Yukon over the past two decades, which has pushed the First Nation to voluntarily refrain from fishing for one of their main traditional food staples since 2013 (Gignac). Addressing this problem at a local level, the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in aim to plant up to 30,000 salmon eggs per year to bolster these numbers at their source, and hit about a third of this target in 2018 and 2019.

The Dawson City Management Plan and the Dawson Regional Planning Commission aim to address other factors of sustainable living in the region, but the first theme of the Dawson Regional Planning Commission is on a sustainable economy. The words included describe the need to balance economic interests with ecological, cultural, and social values, and does this with the express intent of ensuring that future generations are able to benefit from the wealth and abundance of the region (“Dawson Regional Planning Commission”). The Dawson Regional Planning Commission contains much of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in’s traditional territory and includes the area that the component sites of the Tr’ondëk-Klondike nominated world heritage site rest upon.

The Dawson City Management Plan also describes the need to address all aspects of community sustainability, including the built, economic, cultural, and natural environments. However, there is a focus here as well, this time on the historic character of the Dawson City community. Concerns for reducing emissions and consumption and improving farming activities are included, but come after calls to protect all of the historic buildings in the community (City of Dawson and Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in 17, 27).

As is shown in all of the above examples, the various stakeholders in this region generally understand that sustainable practices require looking broader than at one single pillar of sustainability. It is completely natural that some of the focuses of the stakeholders will differ, but that unfortunately implies that these intersecting policies and plans will be less sustainable, as explored in the measurement section to follow.

Measurement

As this case study addresses a proposed world heritage site, it is not yet possible to measure the impacts of that nomination. What can be measured though, and may be obvious based on the preceding sections, is what the process of creating policies and plans has looked like. A first note is that the world heritage nomination package and the Dawson Regional Planning Commission had similar stakeholders, but had fairly different results.

Even though the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in are listed as a major contributor and one of two parties (with the Yukon Government as the other) to have primary responsibility for implementation of the plan, the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in had many criticisms to make on the draft Dawson region plan. Presented as a major stakeholder and contributor, the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in public feedback document noted that a reflection of their traditional knowledge and experience, life, and values appeared nowhere in the document, representing a lack of understanding of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Final Agreement (“Dawson Regional Planning Commission”).

The Dawson Planning region overlaps with 75% of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in traditional territory, and also overlaps traditional territories of two other First Nations. To reiterate again though, there is no reference to the Umbrella Final Agreement and does not incorporate the UNDRIP principles into the plan. Feedback to the draft plan shows multiple shades of gray, making it clear that many of the collaborators were not happy with the draft plan. This included a hope for further support of the mining sector as an economic driver but also protection and love for the ecological characteristics of the region (“Dawson Regional Planning Commission”). From a certain point of view, this failure to satisfy any major group shows a failure to truly collaborate.

Moving to the 75 km stretch of river and sites included in the nomination site, 5 of the 8 component sites already have their own management plans, and if inscribed these sites would be guided by these plans. The plan for the other three is to have them managed according to existing legislation. Part of the reason for this is to keep the site simple, to keep the story true and communicate values in relatable and understandable ways (“Tr’ondëk-Klondike World Heritage Status”).

Several problems lie in this approach. First of all, in the Moosehide Community Management Plan it is very clearly described as not being a heritage site as it is an active residential community, and so any cultural management must prioritize residents’ daily life in the village (Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in and Moosehide Advisory Committee 3).

At the other end of the spectrum, the Dawson City Heritage Management Plan has strict goals to preserve, strengthen, and conserve the visual character of the Gold Rush era landscape (Commonwealth iv). The Forty Mile, Fort Cudahy, and Fort Constantine Historic site management plan includes specific reference to being open to improvement and as intending to meet the requirements and spirit of the Umbrella Final Agreement (Campbell et al. 1).

As the Dawson City municipality was involved and Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation took the helm in creating the nomination package it is likely that these management plans are conceived as fitting within the World Heritage inscription. However, these examples show significant differences in how the sites have been represented, and arguably do not fit within the goals of the current nomination package.

There are significant problems in the collaboration processes that resulted in these plans, especially noteworthy for documents that claim to rely so heavily on collaboration. Most also mention the importance of considering sustainability goals within context of each other, yet rarely seem to succeed in any sustainability goals. In 2022 there will likely be a decision on this nomination package, and ideally greater collaboration between parties will allow a satisfactory continuation of this process.

Works Cited

Book chapters, articles

- Campbell, Judy, Eileen Fletcher, and T. J. Hammer. “Forty Mile, Fort Cudahy and Fort Constantine Historic Site Management Plan.” 2006.

- Gignac, Julien. “How Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation aims to revitalize critical salmon stocks in Yukon.” The Narwhal, 27 May 2020.

- Neufeld, David. “A Cultural Cartography of the Tr’ondëk-Klondike: Mapping plural Knowledges.” Special issue of Zeitschrift für Kanada-Studien vol. 67, 2018.

- Roburn, Shirley, and Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Heritage Department. “Weathering Changes: Cultivating Local and Traditional Knowledge of Environmental Change in Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Traditional Territory.” Arctic, vol. 65, no. 4 (Dec 2012), 2012, pp. 439-455.

- Ruhanen, Lisa and Michelle Whitford. “Cultural heritage and Indigenous tourism.” Journal of Heritage Tourism, Vol 14, no 3, 2019.

- Wilson, Nicole J., Leila M. Harris, Angie Joseph-Rear, Jody Beaumont, and Terre Satterfield. “Water is Medicine: Reimagining Water Security through Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Relationships to Treated and Traditional Water Sources in Yukon, Canada.” Water, vol 11, no. 3, 2019.

Reports, policies

- City of Dawson, The, and Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in. “After the Gold Rush: The Integrated Community Sustainability Plan.” 1 Mar. 2007.

- Commonwealth Historic Resource Management Limited. Dawson City Heritage Management Plan. 2008.

- “Dawson City’s UNESCO World Heritage bid put ‘on hold’.” Cbc.ca, 25 May 2018.

- Dawson Regional Planning Commission, The. 2019, https://dawson.planyukon.ca/index.php, accessed October 20, 2021.

- Green, Heather. “Historical Mining and Contemporary Conflict: Lessons from the Klondike.” NICHE Canada, 2 May, 2018.

- Parks Canada. Klondike National Historic Sites of Canada Management Plan. 2018.

- Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in and Moosehide Community Plan Advisory Committee. “Moosehide Community Plan.” 2016.

- Tr’ondëk-Klondike World Heritage Nomination. Tkwhstatus.ca, 2021. Accessed 24 Nov. 2021.

- “Umbrella Final Agreement.” Council of Yukon First Nations. Accessed Nov 24 2021.

- “Yukon UNESCO World Heritage bid shifts focus from Gold Rush to Colonialism.” Cbc.ca, May 25 2021.

Banner image credit: Photo of (View of Dawson City from Moosehide Trail) or (Tr’ondëk-Klondike area taken by Neil-Macdonald). Hosted on World Heritage nomination status homepage.