Case Study prepared by Andrew Silver, Carleton University

Reusing and Recycling Historic Buildings: A Toolkit of Strategies to Reuse Materials That Are No Longer Useful (Halifax, Nova Scotia)

KEYWORDS materials reuse, waste, sustainability, historic buildings, demolition.

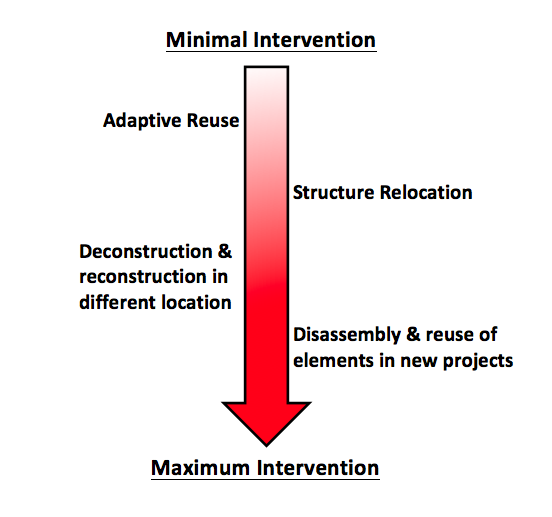

When buildings are no longer useful for their original purposes, there are four main methods for reusing these buildings to reduce waste. The Ecology Action Centre, a non-profit ecological activist group based in Halifax, Nova Scotia, developed a comprehensive toolkit containing strategies to reuse buildings (or at the very least their materials/components) to reduce waste and conserve heritage. These strategies are: adaptive reuse, structure relocation, deconstruction and reconstruction in a new location, and deconstruction and reuse of materials in new projects. Different situations require different approaches: the path with the least impact on historic buildings must be balanced with the path with the least environmental impact, which also must be balanced with the path of least financial impact. The Ecology Action Centre Waste? NOT! Toolkit is an excellent resource for helping individuals make sustainable decisions affecting the futures of historic buildings. It promotes environmental, social and economic sustainability, while also promoting the conservation of heritage.

PROJECT DESCRIPTION(S)

As mentioned above, when buildings become no longer useful for their original purpose, instead of just being demolished and scrapped. Buildings can be moved to new property to be reused in a different location, they can be retrofitted to serve a new purpose, they can be deconstructed and reconstructed in a different location or they can be carefully deconstructed and their components can be saved for future projects.

The Ecology Action Centre office offers an excellent example of an adaptive reuse project. The building was once a residential building, and was also used as an electrical supply store. The Ecology Action Centre renovated it to transform it into their office; their success inspiring many others to undertake adaptive reuse projects. Image Source: https://c1.staticflickr.com/1/63/378824182_9c80b1d2e0_z.jpg

Adaptive Reuse: Ecology Action Centre Office (2705 Fern Lane, Halifax, NS) Adaptive reuse involves renovating existing buildings to serve a different purpose. For example, a building that used to be an apartment building could be transformed into an office building. One excellent example of an adaptive reuse is the Ecology Action Centre Office in Halifax, NS. The Ecology Action Centre is a local non-profit that “respects and protects nature and provides environmentally and economically sustainable solutions for its citizens” (Ecology Action Centre). In 2005, the Ecology Action Centre purchased a 130-year-old house for its office. It took them roughly ten months to transform the building into their office. Once completed, the building was energy and water efficient, using natural, low-impact materials. The project was undertaken not only to create an office for their organization, but also to inspire “hundreds of property owners and builders to make greener choices.”

Currently, the Ecology Action Centre is exploring further renovations to the building. They have recently decided to add a third storey to the building and to finish their basement, as well as to make further improvements to the buildings efficiency. They need to expand their office as their organization has grown, and they want to do so sustainably. By finishing and insulating their basement, they will reduce energy consumption by reducing heating needs. By adding a third storey, they will save money by not having to construct a new building and will not have to increase their geographic footprint.

The Morris House, built around 1764, was moved to its new location at 2500 Creighton Street and work has begun to transform it into an affordable housing building for 9 youth. Image source: http://thekitchensinkproject.blogspot.ca/2013_01_01_archive.html

Moving Buildings: Morris House (2500 Creighton Street, Halifax, NS) Traditionally, buildings have been moved for many different reasons. Sometimes, they needed to be moved because of natural reasons (rivers, flooding, winds). Today, buildings are still being moved, but it has become much more difficult because of many restrictions. Moving buildings is an excellent way to preserve buildings that would otherwise have to be demolished because of development (Addis, 2006, p. 104). Power lines above roads make it quite difficult to plan a route given the height restrictions from the lines. Also, roads have certain weight limits, which prevent heavy trucks from passing down certain roads. Finally, police escorts may be needed, which are very costly. While it still is possible, careful planning needs to take place and a cost analysis needs to be done prior to undertaking the project.

The Morris House is an excellent example of a structure that was moved to a different location, so that the building could be reused in a different purpose. It was once the office of Charles Morris, Surveyor General of Nova Scotia. Now, it has been moved closer to downtown Halifax, and is being renovated into affordable housing for youth. The building, which was at risk of being demolished, is roughly 250 years old. A development was approved for the land it was located on. After performing an assessment of the costs, the Morris House team has determined that moving the building and renovating it will be two-thirds of the cost of building a new, comparable building (The Joint Action Committee on the Morris, 2013, p. 4). Therefore, not only has moving the house helped to preserve a historic building, it has also allowed a non-profit organization to create affordable housing units at a reduced cost to new construction.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FPADFvugvM4]

This 180-year-old barn was disassembled, restored and reassembled in a new location, and was then converted into a private home. Image source: http://www.balticwoodworking.com/photos/timberframingpics/turner-barn.jpg

Deconstruction: Turner’s Barn (Jeddore, NS – part of Halifax Regional Municipality) If buildings are unable to be moved in one piece, it may be viable to deconstruct the building (take it apart) and reconstruct it in a different location. This can sometimes be easier than moving the entire building but can also be more complicated, as it is necessary to be able to fit the pieces back together. If there is not an appropriate route to transport the intact building, it may be best to disassemble it. Further, if the building is not in an appropriate condition to be transported in one piece, it may be best to disassemble it and move it like that. For example, the Ecology Action Centre Toolkit discusses cases of buildings (wooden buildings in particular) being disassembled and reassembled in a different location.

Specifically, they discuss a project involving a barn that was built in 1834. “Turner’s Barn”, located in Jeddore, Nova Scotia, was to be demolished, but a client had it disassembled and the materials were restored. They were then transported to her property, where it was reassembled to become the client’s home. The contractor added new windows (there were no existing windows in the barn) and a new roof , but all of the wood and framing was reused. The original shape of the barn is the same and the wood is the same, but the look of the barn, because of the new roof and windows, has changed somewhat. The materials from the barn (mainly wood) would have gone to waste had the barn been demolished.

Many different types of building materials can be reused in new projects, including the lumber seen here. As long as the materials meet a required integrity, they are able to be reused. Image source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/6/6f/Dangar_Bridge_Timber.JPG

Materials Reuse If buildings are not able to be adapted to new uses, not able to be moved, or not able to be deconstructed and reconstructed in a new location, they may need to be demolished, However, if care is taken during demolition, materials may be salvaged for use in future projects. In Nova Scotia, it is estimated that 60% of construction waste comes from renovations, 20% from new construction and 20% from demolitions (Ecology Action Centre, 2010, p. 16). While some waste is inevitable, there are strategies that can be used to mitigate the waste and reuse as many supplies as possible. Any building materials that are in decent condition can be reuse. This includes: bricks, stone, lumber, flooring, siding, windows and others. In most circumstances, the use of these products will have to be approved by a structural engineer, so that it can be determined that they are structurally acceptable.

If they are determined to be acceptable, these products can be used in future building projects. For example, lumber that was used to frame the previous building can be used for framing in the current project. If the materials are not determined to be structurally acceptable, there are still many uses for salvaged materials. For example, bricks can be used to create paths or gardens. Many materials from old buildings may be of higher quality than those used in buildings today. One example of materials reuse is the Habitat for Humanity ReStore. These stores are stocked with new donated building supplies as well as used building supplies in good condition. Not only does this store divert waste from landfills, it also provides building supplies at reduced cost for those who are most in need. It allows projects to be completed at lower costs than by using new materials, generally without sacrificing quality.

TIMELINE

- The Ecology Action Centre was formed in the 1970s, from a Dalhousie University course entitled “Living Ecology.” Its first mission was to promote recycling in Halifax. Over the years, it has expanded, focusing other environmental and social issues.

- In 2006, the Ecology Action Centre purchased a 130-year-old building, which it renovated into its eco-friendly office.

- Finally, in 2009, the Ecology Action Centre became involved with a project started by the Heritage Trust of Nova Scotia – the Morris House.

- In, 2010, it released its “Waste? NOT! Toolkit” to promote the reuse of historic buildings, and the reduction in waste.

- In early 2013, the Morris House was moved across Halifax, to be repurposed as affordable housing for youth.

STAKEHOLDERS

Adaptive Reuse – Ecology Action Centre Building:

- Ecology Action Centre (owner of building)

- Tekton Construction (contractor)

- Solterre Design (Design firm)

- Volunteers (the majority of the renovation work was done by volunteers)

- The community

Structure Relocation – Morris House:

- Heritage Trust of Nova Scotia (owner)

- Metro Non-Profit Housing (not for profit housing organization in Halifax)

- the ARK (a community organization that works with homeless youth)

- Halifax Regional Municipality (the municipality the development is located in)

- 9 occupants of the affordable housing units being built

Deconstruction and Reconstruction in a different location – Turner’s Barn:

- Owner (unnamed)

- Baltic Woodworking

- Tenants of house (2 apartments)

Disassembly and reuse of elements in new projects:

- Habitat for Humanity ReStore

- Waste Management Organizations

- Municipalities

- Contractors

- Demolition Companies

NATURAL-CULTURAL HERITAGE

This project mostly deals with cultural (built) heritage, as it deals with buildings. Some buildings that are being reused may have heritage designations. However, both the Morris House, the Ecology Action Centre office and Turner’s Barn are historic buildings that do not appear to be designated, however they are 250 years old, 130 years old and 180 years old respectively. They do not appear to be part of heritage conservation districts either. While they are not designated, it does not mean that they do not deserve protection and should not be preserved. The Morris House, for example, is Halifax’s fourth oldest building, and the previous home of one of the founders of Halifax area.

This figure shows the types of projects discussed in the toolkit and ranks them by their level of intervention.

While heritage designation often means legal protection, it does not necessarily mean that places that are not designated are not important. However, buildings that are not designated do not have the same restrictions, meaning that non-designated buildings may be renovated more easily. However, when working with non-designated buildings, an approach of minimal intervention should be taken whenever possible. The Standards and Guidelines for the Conservation of Historic Places in Canada is an important document, and should be followed when renovating any historic building, not just one that is designated.

SUSTAINABILITY

- This case study relates to environmental sustainability as these strategies can help reduce waste and reduce energy consumption. Using less non-renewable resources means that more will be preserved for future generations, and less will end up in landfills. Also, reusing existing materials saves the energy that would normally be necessary to manufacture more of these materials. Further, in the case of reusing a building through moving and adaptive reuse, energy associated with construction will be saved.

- This topic also relates to economic sustainability, as reusing materials and buildings could potentially save money and conserve resources. While reusing materials and buildings might not always be economically sustainable, an analysis needs to be done to determine the potential cost differences. For example, if examining the possibility of an adaptive reuse, if the building that is to be renovated requires extensive work in order to useable, it is possible that it could be cheaper to build a new building. If the moving costs of a building are very high because of complications, new construction might be more economically sustainable. However, deconstructing the materials and reusing them for other projects is always economically sustainable. Adaptive reuse, materials reuse and structure relocation, in most cases, are economically sustainable. Overall, they encourage the conservation of resources, as well as encourage resources to be spent efficiently.

- Moreover, this topic is also connected to social sustainability. Historic buildings can be reused for many purposes. Economic savings of reusing historic buildings as compared to using new construction can allow non-profit organizations such as affordable housing organizations to repurpose buildings for community uses. The Morris House is an excellent example of a socially sustainable project. The house is being repurposed for affordable housing units, so that nine youth that would previously be on the street will now have a house to live.

- Further, recycling building elements is also very socially sustainable. An organization such as Habitat for Humanity ReStore sells recycled building materials to communities for discounted prices. This means that individuals and families that otherwise may not be able to afford safe housing are able to purchase quality products at low prices. This also allows houses to be built at lower costs, meaning that more people will have access to affordable housing that they own.

MEASUREMENT

It is extremely important that decision about what to do with buildings do not just revolve around costs. Many other factors need to be considered when making a decision to renovate, move or demolish a building. The Athena Institute has introduced a way to calculate the energy that has already gone into the construction of the building and the amount of “Global Warming Potential”. This tool is called the “ATHENA EcoCalculator”. Specifically, it measures the embodied primary energy in the buildings individual components, including: columns and beams, floors, exterior walls, windows, interior walls and roofs. This includes all energy in raw materials, energy in transportation and any other energy associated with the materials or construction (Athena Institute, 2009, p. 4) .The average energy of the materials per square metre is calculated and then the size of these materials is calculated. The energy and Global Warming Potential of the demolition of the building is then added to this analysis. The total energy and Global Warming Potential of the building is then calculated.

However, it is also important to measure the financial aspect of the project to determine the financial viability of the project. While a life cycle assessment is necessary to determine environmental impacts, this must be balanced with a financial analysis of the different options. It is necessary to compare the costs of new construction to that of moving and renovation, to determine if the project makes financial sense. If the costs of new construction are higher than the combined cost of moving (if applicable) and renovation, the project is financially viable. In the case of the Morris House, for example, the Heritage Trust of Nova Scotia determined that they were saving approximately one third of the cost of new construction by moving the house and renovating it, therefore they made the decision to proceed with the project.

Further, in the case of the Ecology Action Centre’s office project, it is important to measure the impact the project had on the surrounding community. As mentioned above, the project was meant to inspire the community to take on projects of a similar nature. Also as mentioned above, it appears that many people were influenced by the project and many did undertake similar projects. The affect these projects have on communities is extremely important. The Ecology Action Centre is an organization that claims to care about the environment and advocates for economic and environmental sustainability, the fact that they actually undertook a project that encompasses both of these principles is outstanding.

It is also necessary to measure the impact that these measures will have on heritage. In his book “Building with Reclaimed Components and Materials”, Bill Addis discusses the “Delft Ladder” – a tool to measure the impact of specific actions on heritage (Addis, 2006, p.15). While the sustainability, and specifically environmental sustainability is very important, conserving heritage is equally important. The route with the lowest effect on heritage should always be taken, when possible.

SOURCES

Books

- Addis, Bill. (2006). Building with reclaimed components and materials. Bodmin: MPG Books Limited.

- Crawford, Robert H. (2011). Life Cycle Assessment in the built environment. New York: Spon Press.

Academic Articles/Reports

- Athena Sustainable Materials Institute. (2009). A Life Cycle Assessment study of embodied effects for existing historic buildings. Retrieved from http://www.athenasmi.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/Athena_LCA_for_Existing_Historic_Buildings.pdf.

- Barliant, Claire. (2010). Adaptive reuse: New strategies in response to the housing crisis. A Journal of Art, Context, and Enquiry, 23, 108-119.

- Poon, Ben Ho-Sing. (2001). Buildings recycles, city refurbished. Journal of Architectural Education 54 (3), 191-194.

- Shen, Li-yun and Craig Langston. (2009). Adaptive reuse potential. Facilities, 28 (1/2), 6-16.

Websites

- Ecology Action Centre. (2010). Waste! Not? Toolkit. Retrieved from https://www.ecologyaction.ca/files/images-documents/file/Built_Environment/cdtoolkit/WasteNOT.pdf.

- Ecology Action Centre. (n.d.). 2014-2015 Fern Lane expansion. Retrieved on November 22, 2014 from https://www.ecologyaction.ca/expansion2014.

- Habitat for Humanity ReStore. Retrieved November 22, 2014 from http://www.habitatncr.com/index.php/restore/restore-overview.

- Jeffrey, Colin. (2011). Construction and demolition waste recycling. Retrieved from http://www.dal.ca/content/dam/dalhousie/pdf/sustainability/Construction_Demolition_Waste_Recycling.pdf.

- Joint Action Committee on the Morris, The. (2013). Moving the Morris House. Retrieved from https://www.ecologyaction.ca/files/images-documents/Morrisbackgrounder_January2013.pdf.

- Murnaghan, Aaron and Kim Thompson. (2011). Saving the Morris Building. Retrieved from https://www.ecologyaction.ca/files/images-documents/file/Mar22_11_%20Morrisktbackgrounder_compressed.pdf.

- Regional Waste Reduction Coordinators of Nova Scotia. (2013). Management guide for construction and demolition debris. Retrieved from http://www.wastecheck.ca/pdfs/2014/CandDManagementGuide.pdf.