Social Sustainability and the Culture of Outports

Port Union, Newfoundland and Labrador

Case Study prepared by Heather LeRoux, Carleton University

KEYWORDs Social sustainability, Community, Outport, Port Union, Industrial heritage, Education.

LESSONS LEARNED The Culture of Outports project uses the unique character of outport communities to create small scale interventions or reuse projects which highlight a community’s unique identity and cultural heritage. In 2013, Port Union, Newfoundland and Labrador collaborated with ERA Architects and the Culture of Outports to create a new recreational outdoor space, park and boardwalk to celebrate the unique culture and heritage of their community. To initiate a project like this in the context of a Newfoundland outport requires an intimate knowledge of the culture and history of the place, as well as the integrated involvement of community members. So far they have managed to do this successfully, and with the right plans to move ahead and willingness to respond to change, the Culture of Outports initiative can be socially and economically sustained for future generations.

DESCRIPTION This project was inspired by the idea of shipbuilders as community builders, as was traditionally experienced in Newfoundland and Labrador outport communities.1 ERA Architects in collaboration with students and community members take on a new town each year, engaging the community in a build project that reflects the historic and cultural character of each town that they visit. Projects so far have taken place in Burlington (2011), Brigus (2012), Port Union (2013), and Botwood (2014).

Port Union, Newfoundland and Labrador is located in the Northeast corner of the province, on the Eastern side of the Bonavista Peninsula looking over Trinity Bay. Founded in 1916, Port Union is the only town in North America founded by a labour union and was the headquarters for the Fishermen’s Protective Union (FPU) lead by William F. Coaker. The Fisherman’s Union was organized as early as 1908, as Coaker traveled around to various outports to gain support. By 1914 over 20,000 men were signed up for the union, and construction of Port Union began on the coast of Trinity Bay.2

The town of Port Union is set apart from other Newfoundland outports in that it was planned and designed with a specific intent, rather than happening organically like the sporadic settling of other outports. Architecturally, buildings in Port Union are emulate a traditional outport Newfoundland vernacular style, however some buildings are larger in scale due to the prominence of commercial and industrial structures.3 With its union organisation, Port Union was also unique beacause residents also relied on the union for most of its services, making the town mostly self-governed for the early part of the 20th century in pre-confederation Newfoundland.

Fisherman’s housing, Port Union, Newfoundland and Labrador. Photo: CBC The Sunday Edition with Michael Enright “Documentary: We Are Leaving Mr. Coaker.” (2012)

With Historic Port Union as the backdrop, ERA Architects and their team of students from Ryerson University lead the development of a community build in Trinity Bay North (amalgamated towns of Port Union, Melrose, Catalina, and Little Catalina) for the Culture of Outports project in 2013. For Port Union, the main community build project consisted of the creation of a new community gathering space and park in the heart of historic Port Union facing the harbour, as well as an extension to an existing boardwalk.

For their community build projects, the Culture of Outports outlines seven main objectives:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Using these objectives, the Culture of Outports aims to create place based initiatives that can be used by the communities to protect and celebrate their heritage resources, as well as assist in the sustainable development of each community.

TIMELINE (Port Union)

1908 The Fishermen’s Protective Union is formed.

1916 Founding of Port Union by Sir William F. Coaker.

1918 Fisherman’s Union Trading Company move operations to Port Union.

1945 Fire impacts a large section of Port Union, the industrial and commercial buildings are rebuilt in a similar style to those before.

1946 Buildings that are rebuilt include the Salt Fish Plant, FU Trading Company Store, Union Electric Company Office, Hotel/FU Trading Company Office, and the Holy Martyrs Anglican Church.

1949 Confederation, Newfoundland joins Canada.

1950 FPU continues to operate and export cod throughout the 1950’s

1992 Declining fishing opportunity resulted in the cod moratorium, limiting

fishermen’s ability fish in Newfoundland and Labrador and further straining the economy.

1995 The Sir William F. Coaker Heritage Foundation is founded.

2004-5 Completion of the Factory building restoration.

2013 ERA Architects take the Culture of Outports project to Port Union.5

STAKEHOLDERS (Culture of Outports and Port Union)

- ERA Architects The driving force behind this initiative is ERA Architects based out of Toronto, with principal ERA Architect Philip Evans at the helm. Several representatives from ERA participate in the projects from year to year.

- Ryerson University, Dalhousie University To execute the projects in various communities, ERA enlists the help of students to assist with the build and learn various skills while working in a community. Since 2011, ERA has brought students from Ryerson University and Dalhousie University along on different projects. For the 2013 Port Union project, five students from Ryerson’s architectural science program travelled to Newfoundland to take part in the initiative during the two-week build and assisted with the initial research.

- Centre for Growth and Urban Renewal Another partner in this project is the Centre for Urban Growth and Renewal (CUG+R), a not for profit research group promoting the sustainable development of rural and urban environments. CUG+R was co-founded by ERA Architects and planningAlliance (pA) in 2009.

- Municipality of Trinity Bay North The town of Port Union and the larger Trinity Bay North area, as inhabitants of the land, they will be the primary users of the space and stewards of the site.

- Sir William F. Coaker Heritage Foundation In a town that is intimately connected to the history of its founder, the Coaker Heritage Foundation is a group of volunteers who are dedicated to the preservation of the Port Union Historic District, on which the Culture of Outports project lies.

- Parks Canada and The Heritage Foundation of Newfoundland and Labrador Port Union is a National Historic Site of Canada, as well as designated as a provincial heritage district by the HFNL.

NATURAL/CULTURAL HERITAGE The heritage values associated with historic Port Union encompass many layers. The town itself is representative of an “outstanding example of a significant social phenomenon, that of the establishment of a union town noted for its commercial success in the face of aggressive competition from commercial merchants in Newfoundland.”6 Part of Port Union’s historic value is that very little of the industrial and commercial buildings have been changed since the town was founded, with the exception of some buildings which were damaged by a fire in the mid-1940’s but rebuilt with the same character and function as the initial buildings.

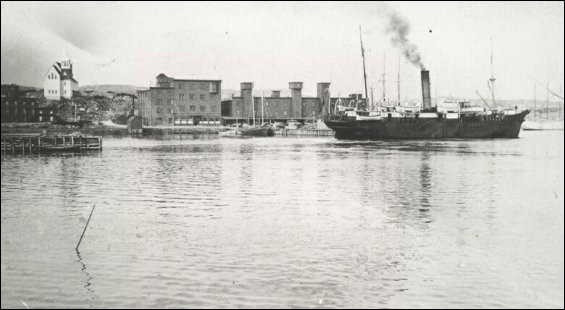

View of Port Union from the Harbour. Photo: Sir William F. Coaker Foundation Collection, Memorial University Maritime History Archive. No date.

Another aspect to the heritage value of Port Union is the districts connection to the hydro-electric power station, dam, and reservoir which are all included in the designations. The connection of the town to the historic hydro plant adds an additional layer of the industrial heritage value to the site. Historic Port Union also has heritage value connected to nature, as the Statement of Significance on the Canadian Register of Historic Places suggests, the town was informally planned to reflect the geography of the site and connection to the harbour side area.7

Because of its uniqueness, Port Union has been awarded several heritage designations at the municipal, provincial, and federal level. The heritage designations and years of recognition are listed below:

- Port Union Registered Heritage District, Provincial – Heritage Foundation of Newfoundland and Labrador (2006)

- Port Union Municipal Heritage District, Municipal – Newfoundland and Labrador Municipalities Act (2005)

- Port Union Historic District National Historic Site of Canada, Federal – Historic Sites and Monuments Board (1998)

SUSTAINABILITY As a town that is closely connected to its labour history, the socio-economic sustainability of Port Union, as with many other outport communities has been tied to its dependence on, and eventual loss of industry. After the decline of the cod fishery, seen most heightened in the early 1990’s with the cod moratorium, many communities across Newfoundland and Labrador lost their main source of income and industry, as well as a fundamental part of their cultural identity.

Like other regions that had been previously reliant on commercial industry, Newfoundland and Labrador experienced a shift towards tourism industries and promotion of heritage resources as a means to generate some of the income that had been lost. In Port Union, it should be noted that the Sir William F. Coaker Heritage Foundation was assembled in 1995 in a concentrated effort to conserve the built heritage of the town. The result has been multiple levels of recognition for Port Union, which can have tourism benefits and attract more visitors to the area. The Culture of Outports project assists in this process by creating a visually appealing outdoor space that can be used by both residents and the visiting public alike to experience the historic town and look out at the natural beauty of the harbour.

In the Port Union project, Culture of Outports was environmentally sustainable in the reuse of materials used in the creation of the boardwalk and archways near the old Coaker buildings. They recycled surplus material from the wharf, repairs, and previous projects to create an intervention that was as sensitive as possible to the existing structures.

Inspired by the idea of barrel arches that were often constructed used as a greeting for Sir William F. Coaker, the project in Port Union included these posts which are meant to emulate the barrel arches, as well as a new outdoor space, seating area, boardwalk extension, and fire pit. Photo: Foundation Square, Port Union. ERA Architects 2013. http://www.eraarch.ca/2013/port-union-success/

Also to consider with regards to social sustainability is the role that students play in the development of the projects, and their interactions with the communities. As noted by Green et al. in “Living heritage: universities as anchor institutions in sustainable communities,” students often have a significant role to play in the development of sustainable heritage development in communities.8 The participation of the students coming in from Ryerson and Dalhousie Universities in conjunction with each community is essential to the build in each town. As a province that has seen a loss of industry and at times a loss of its youth, the students involved in the Culture of Outports project can provide communities with a fresh perspective on cultural resources and can help to inspire youth in these communities which have often been heavily affected by patterns of out-migration.

In addition, the overall longevity of the Culture of Outports project as a whole should be considered with respect to sustainability. While the projects themselves are successful as place-specific and independent, it would be interesting to see if the communities involved in the Culture of Outports projects could create a network to share ideas of how to promote their unique communities which all have the common thread of connection to the larger Culture of Outports initiative. Collaborative discussions on how each of the projects can be used or promoted could be beneficial in ensuring that their stewardship and longevity are maintained through future generations and can be actively sustained without outside intervention. One possible strategy could be to develop a conservation or place-based management plan that could be used by each of the individual communities.

Community build days, Foundation Square – Port Union, Newfoundland and Labrador. Photos: ERA Architects, Culture of Outports Port Union Blog “Build day 3” and “Mission Accomplished” 2013. http://cultureofoutports.com/community_category/port-union/

MEASUREMENT In this section, Culture of Outports will be evaluated using Chris Landorf’s evaluation criteria for social sustainability as outlined in “Evaluating Social Sustainability in Historic Urban Environments.” Although the Port Union example is outside of what would normally be considered the “urban context,” Landorf provides useful criteria which inform a good model for which social sustainability can be successfully evaluated. For the purpose of this evaluation, criteria relating to the availability of basic goods and services for the population have been removed based on relevancy to the scope of this case study, and the nature of the Culture of Outports project.

- Social infrastructure (cultural events, historic resources and recreation facilities) Cultural events took place during the development of the Port Union project, consisting of various gatherings around town and at the project site. The project actively used the public space surrounding the Coaker industry buildings in the central area of town. Culture of Outports created a inventory of tangible and intangible resources, and used them in the creation of outdoor recreation facilities to be used by the town.

- Stability (institutional continuity, effectiveness, investment, reliability, turnover and trust) Institutional continuity is met as ERA takes the lead and provide the framework for which the project takes place. Culture of Outports are successful in effectiveness because they respond to the environment and the cultural and historical significance of a place to produce something that is useable to the community long term – community consultation is essential in this as well. Investments for this project are contributed from various heritage and community organizations, as well as TD Canada Trust and the Canada Council for the Arts. The Culture of Outports have also succeeded in building reliability since they began the first intervention in 2010, being approached by communities and invited in is a good sign. Turnover and trust is successful when communities are adequately consulted and there are existing groups or people in town who are willing to take the projects on long term to ensure their overall sustainability.

- Flexibility (institutional adaptability and innovation inter-organisational partnerships and effective negotiated outcomes) The Culture of Outports as a project is inherently flexible as it adapts to the different communities needs and wants, the project also has institutional adaptability as well as participants change from year to year, as well as the partners involved.

- Networks (informal social ties and formal community associations and organisation) From the beginning it appears the Culture of Outports team are welcomed in and easily integrated into the communities. Culture of Outports works in conjunction with existing heritage or historical organizations as well as municipalities to create projects that are in the interest of all parties involved. Various social media platforms and blog posts are maintained and can be easily accessed by community members, as well as be viewed from afar – this contributes to the aspect of giving back to the community and recording the process for them.

- Participation (broad scope and equitable influence on decision making, voter turnout, volunteering and charity work) Members of the community are welcomed and asked to participate in the community build, and is an important aspect of the main idea of the project. It is unclear how decisions are made with regards to project development, or how ‘equitable’ it is.

- Identification (association with community and place, understanding of heritage values) A considerable amount of research goes into the creation of these projects in order to understand the history of the communities, as well as the values that the communities see as important. An effort is made to become familiar with all of the town’s surroundings and built and natural form in preparation for the project.9

In evaluating the social sustainability of the Culture of Outports project, it is also helpful to examine whether or not it appears that the objectives set out were fulfilled. Below is an evaluation of the objectives of Culture of Outports, as described above in the Description. With respect to their objectives of Livable Communities First, Regional Perspectives, New Uses for Existing Places, Cross Generational Engagement, Place Based Economies, Incremental Growth, Community Values, all seem to be met in the Culture of Outports project. However, the prospect of incremental growth and the development of a place based economy are objectives that would need to be taken on by the community and evaluated in later years.

Future evaluation and research could consider the demographics of Port Union and Trinity Bay North, and how that is reflected in the community participation of the project and community build. Comparative case studies could also look at potential initiatives in other provinces with towns that have unique labour histories, or an examination of another Culture of Outports project that does not have the same context of heritage designation as Port Union, such as the community build that took place in Botwood in 2014.

In conclusion, using the various criteria above it appears that Culture of Outports project is socially sustainable because of the amount of community consultation and interaction that ERA and other partners have with the people who live in Port Union. What could make the social sustainability of the Culture of Outports stronger is a plan that better integrates the projects taking place in all of the individual communities in an effort to provide the communities with information that they can use and pass on to future generations to become stewards of their heritage resources.

SOURCES

[1] Philip Evans (2013). “The Culture of Outports Project,” in Calvin Evans, Master Shipbuilders of Newfoundland and Labrador Volume One: Cape Spear to Boyd’s Cove. St. John’s: Breakwater Books. P. 216.

[2] Sir William Ford Coaker Heritage Foundation, (2006). “Our History.” Retrieved Nov. 18, 2014 from: http://www.historicportunion.com/en/ourhistory.html

[3] Andrea O’Brien and Debbie O’Reilly (2006). “Architectural Survey of Port Union, NL. Conducted by Andrea O’Brien and Debbie O’Reilly, June 15-16, 2006. Compiled by Andrea O’Brien,” published by the Heritage Foundation of Newfoundland and Labrador. p. 8.

[4] Culture of Outports, “Objectives.” Retrieved Dec. 8, 2014 from: http://cultureofoutports.com/objectives/

[5] All dates relating to historic Port Union have been taken from “Architectural Survey of Port Union, NL. Conducted by Andrea O’Brien and Debbie O’Reilly, June 15-16, 2006. Compiled by Andrea O’Brien,” published by the Heritage Foundation of Newfoundland and Labrador.

[6] Canadian Register of Historic Places (2007). “Statement of Significance” Port Union Historic District National Historic Site of Canada. Retrieved Nov. 21, 2014 from: http://www.historicplaces.ca/en/rep-reg/place-lieu.aspx?id=7657&pid=0

[7] Canadian Register of Historic Places (2007). “Statement of Significance” Port Union Historic District National Historic Site of Canada. Retrieved Nov. 21, 2014 from: http://www.historicplaces.ca/en/rep-reg/place-lieu.aspx?id=7657&pid=0 http://cultureofoutports.com/community/what-is-it-that-youre-doing-out-there/

[8] Alix Green et al. (2013) “Living heritage universities as anchor institutions in sustainable communities.” International Journal of Heritage and Development. 3.1. p. 7-19.

[9] Information used in this evaluated criteria has been extracted from the Culture of Outports Port Union blog posts and social media pages in 2013. http://cultureofoutports.com/community_category/port-union/

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Evans, Philip (2013). “The Culture of Outports Project,” in Calvin Evans, Master Shipbuilders of Newfoundland and Labrador Volume One: Cape Spear to Boyd’s Cove. St. John’s: Breakwater Books. 211-222.

Academic Articles

Green et al. (2013) “Living heritage universities as anchor institutions in sustainable communities.” International Journal of Heritage and Development. 3.1. 7-19.

Landorf, Chris (2011). “Evaluating Social Sustainability in Historic Urban Environments.” International Journal of Heritage Studies. 17.5. 463-477.

O’Brien, Andrea and Debbie O’Reilly (2006). “Architectural Survey of Port Union, NL. Conducted by Andrea O’Brien and Debbie O’Reilly, June 15-16, 2006. Compiled by Andrea O’Brien,” published by the Heritage Foundation of Newfoundland and Labrador.

News Articles

Joy, Kristen (2013). “Designing for the Future: How – and why – Toronto based architects want to help Newfoundland and Labrador.” Downhome Magazine, Nov. 2013, 64-69.

Websites

Canadian Register of Historic Places (2007). “Statement of Significance” Port Union Historic District National Historic Site of Canada. Retrieved Nov. 21, 2014 from: http://www.historicplaces.ca/en/rep-reg/place-lieu.aspx?id=7657&pid=0 http://cultureofoutports.com/community/what-is-it-that-youre-doing-out-there/

Culture of Outports (2013), “Objectives.” Retrieved Dec. 8, 2014 from: http://cultureofoutports.com/

objectives/

Culture of Outports (2013), “Port Union.” Retrieved Nov. 18 from: http://cultureofoutports.com/

community_category/port-union/

Sir William Ford Coaker Heritage Foundation, (2006). “Our History.” Retrieved Nov. 18, 2014 from: http://www.historicportunion.com/en/ourhistory.html