Case study prepared by Stephanie Elliott, Carleton University

Sustainable Neighbourhood Regeneration in Hintonburg, Ottawa, Ontario

KEYWORDS Ottawa, Sustainable community, Cultural Heritage, Social Sustainability

The Hintonburg Community Centre, located on Wellington Street West, next to the St. François d’Assise Church. Photo: Stephanie Elliott 2014.

LESSONS LEARNED

After a fifty-year period of economic uncertainty, high crime rates, and marginalization, the Hintonburg neighbourhood has demonstrated that it is possible for a community to regenerate itself. Members of the community took an active position in the creation of a Neighbourhood Plan and a Community Design Plan to address their concerns about the neighbourhood. The Hintonburg/Mechanicsville Neighbourhood Plan was developed through public consultations beginning in 2006, and was completed in 2010, in a collaborative effort between the City of Ottawa and the Hintonburg Community Association. The Plan focused on making Hintonburg a sustainable community, and made many recommendations for how to do so, incorporating environmental, socio-economic, and cultural considerations. The Wellington Street West Community Design Plan was approved in 2013, three years after the Neighbourhood Plan. It contains parallels and progressions on the themes found in the Neighbourhood Plan, and it provides a framework for achieving community goals through planning.

Based on various measurement tools, Hintonburg has regenerated into a sustainable, walkable community. It is now an up-and-coming neighbourhood west of Ottawa’s downtown core. The neighbourhood is filled with diverse young families and couples, with a growing commercial district on Wellington Street West, and intensification occurring throughout the residential areas on either side of this main artery.

DESCRIPTION

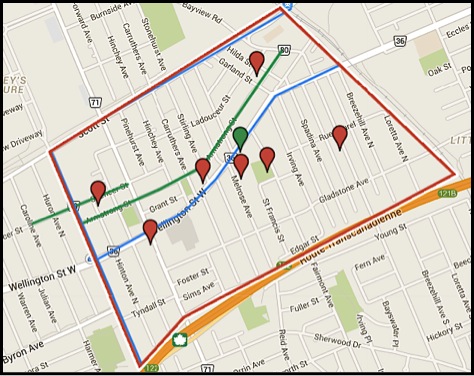

The area is centred on Wellington Street West, and bordered by Scott Street in the north, the Queensway on the south, the O-Train line on the east and Holland Avenue on the West. At times, the neighbourhood is split into North and South Hintonburg, with Wellington Street as the dividing line.[i]

Map of Hintonburg. Red Line: Case Study Boundary. Red Points: Heritage Designated Property. Green Point: Hintonburg Community Centre. Blue Lines: Main City Cycling Route. Green Lines: Community Cycling Routes. Stephanie Elliott via www.mapsengine.com

TIMELINE

- Pre 1818: Algonquin Nation living in the area.

- 1818: Richmond Road built – now called Wellington Street West.

- 1826: First settlers, farmers, building in the area

- 1854: Judge Armstrong Settles and builds his estate, Richmond Lodge, now Armstrong House.

- 1868: Joseph Hinton arrives, and by 1888 secures a town hall and a post office for the community

- 1870: CPR is installed through Scott Street and south from Gatineau

- 1893: Incorporation of the Village of Hintonburg, named after Joseph Hinton.

- 1896: Streetcars are installed along Richmond Road, Holland Avenue, and Byron Street.

- 1907: City of Ottawa Annexation due to population increase after Great Fire of 1900.

- 1907-1960: Growth in prosperity, services, population, etc.

- 1960-c.1999: Community decline – the CPR lines and Roundhouse were removed, more taverns opened, which brought motorcycle gangs, crime, and prostitution.

- 1991: Hintonburg Community Association is created

- 2006-2010: Process and approval of the Hintonburg / Mechanicsville Neighbourhood Plan (NP).

- 2013: Approval of the Wellington Street West Community Design Plan(CDP).[ii]

STAKEHOLDERS

Community members created the Hintonburg Community Association (HCA) in 1991. Initially, the HCA intended to monitor the development applications coming into the community. However, “[t]he founding members learned that… residents were concerned about rising crime rates and prostitution.” The HCA “has established a reputation among developers and city staff for fair consideration of proposals that fit the neighbourhood and fierce opposition to those who do not.” It has also developed social programs to improve crime rates. More recently, the association has collaborated with various groups to turn Hintonburg into an art and culture centre, encouraging independent artists and businesses in the region. Hintonburg is now viewed as a trendy, friendly, and accessible neighbourhood.[iii]

Hintonburg is a neighbourhood of the City of Ottawa. As such, it is subject to development, policy, and management decisions made by the City, including the Official Plan, the Greenspace Master Plan, and the Cycling Plan, among others.

The Wellington West BIA is heavily involved in regenerating the community. It was created by community businesses in 2008 as part of the City of Ottawa’s Wellington Street West reconstruction project. The BIA works with business owners and community members to create a vibrant main street for the Hintonburg and Wellington West communities.

PROJECT DESCRIPTION

The Hintonburg/Mechanicsville Neighbourhood Plan (NP) began in 2006 with a series of public consultations with the community to determine the needs, issues, and successes in the neighbourhood. The NP puts emphasis on the creation of a sustainable community, through the improvement of environmental, socio-economic, and cultural aspects of the area. The Wellington Street West Community Design Plan (CDP) was approved in 2013, three years after the NP was approved, and contains parallels and progressions on the themes found in the NP. Both the NP and CDP are examined in detail below.

The community wants to encourage new development in the area, while maintaining its defining characteristics. The NP addresses environmental concerns such as improving green space access, quality, and safety, and instituting a replanting plan for when trees die. The community also wants to make the area more cycle- and pedestrian-friendly. It addresses socio-economic concerns by ensuring the continuity of existing social amenities and institutions, as well as by attracting new amenities and a diverse group of commercial businesses. The NP details cultural concerns including maintaining and expanding the arts initiatives, while encouraging the re-use of existing buildings and the design of new ones for arts and cultural usage. Additionally, promotion is highlighted as an essential need.

The CDP includes the concerns identified in the NP by creating a framework for the City and for the community to address them, through development and planning policy.

NATURAL/CULTURAL HERITAGE

The heritage value of Hintonburg lies in its origins as one of the earliest industrial settlements in the area. The mix of residents, from mill workers and labourers to judges and civil servants, and their linguistic and religious diversity (French and Irish Roman Catholics, British Protestants), created a neighbourhood that is rich in different services, industries, businesses, churches and architectural styles. It is situated south of the Ottawa River, however the Sir John A. Macdonald Parkway has cut off access to the water. There are six heritage-designated properties within the Hintonburg neighbourhood.

One of the earliest estates built in Hintonburg, Armstrong House was designated as heritage property in 1976 (35 Armstrong Street). Photo: Stephanie Elliott 2014.

- Armstrong House, at 35 Armstrong Street, is one of the earliest estates built in the area, built by Judge Christopher Armstrong in 1854. It was designated as a heritage property in 1976 by the City of Ottawa. It currently houses an advertising firm.

- The former École Sacré-Cœur, at 19 Melrose Avenue was a French Roman Catholic school built in 1912, and stands for the strong Francophone history of Hintonburg. It was designated by the City of Ottawa in 2005 as heritage, and was the site of an award-winning adaptive re-use project in 2011.

- The MaGee House at 1119 Wellington Street West was designated in 1996 as a unique example of Second Empire style in the area. Its constantly changing uses “parallels the evolution of Hintonburg from a village within the Township of Nepean to an urban neighbourhood within the City of Ottawa.” An architecture firm currently occupies it.

- The Former Ottawa Fire Station #11 at 424 Parkdale Avenue was the Fire Station for this area from 1924 until 1986. It was also designated in 1996. A culinary event studio, Urban Element, now uses the space.

- The Capital Wire Cloth Company, at 7 Hinton Avenue, was a factory constructed between 1912 and 1948. It was designated in 2013 for its “historical associations with the pulp and paper industry, and its contextual significance as a unique example of the industrial history of this neighbourhood.” It serves as the Canadian hub for the digital gaming company Fuel Youth Engagement.

- The Robert Mason House at 101 Bayswater Avenue was built in 1981 as a family home, and remained with the Mason family until the late 1990s. After a contentious but defeated development proposal, and is again a private residence.[iv]

SUSTAINABILITY

Environmental Sustainability: There are two main environmental sustainability issues that the Neighbourhood Plan addresses: a commitment to improving public green space and making the community less car-dependent. The first issue is outlined in the NP section entitled “The Green Infrastructure.” This section aims “[to] protect, maintain and … expand green spaces and tree plantings.” There are six parks in the area, which all have one or more problems relating to security and maintenance. Infrastructure is also lacking, such as outdoor furniture and art installations. Only 5% of the Hintonburg area is currently used for Recreation/Open Space. Parkdale Park makes up most of this, and nearly all of the parks are located close to Wellington. “In general, the community is adequately served by the number, size and location of the parks.” Similar issues of security and accessibility are raised here as in the NP.

“Navigating Neighbourhood and City” and “Community Safety and Security” in the NP address walkability and cycling.[v] The former states that “[a]rea residents place an emphasis on walking, cycling, and transit use as preferred modes of travel,” and this section aims to increase this tendency. To do so, bike lanes and better pedestrian crosswalks are needed in the area. Community safety is a high priority for many residents. Better infrastructure, such as bike racks and signage, is needed to welcome the use of lower-carbon transportation.[vi]

Hintonburg Park entrance, from St. Francis Street. The St. François d’Assise Church, in the background on the left, dominates the park. The wall was renovated in 2010. Photo: Stephanie Elliott 2014.

The Community Design Plan addresses transportation as well. It states that because of the grid pattern of the streets, and the presence of sidewalks on most streets, Hintonburg offers pedestrians and cyclists many route options. The CDP describes Wellington, Holland, and Scott as main arteries appropriate for cycling, and Armstrong and Spencer streets as routes within the community. However, as pointed out in the NP, the first three streets are much too traffic-heavy to ride without dedicated bike lanes. Proposals for dedicated and shared-use lanes are ongoing, but not yet implemented.

Socio-economic Sustainability: The Neighbourhood Plan presents Hintonburg as a socially and economically sustainable community, but one that needs some improvement. The community is ethnically diverse, and the area features a large mix of residential, commercial, and institutional uses. There are numerous social initiatives operated by the HCA, which increase connectivity in the neighbourhood, improve education around social issues such as drug use and crime, and offer activities for residents. Residents wish to encourage “independent, locally owned, community-minded businesses” in the area to foster community support and interest. The Wellington West BIA promotes and improves both the building stock and the types of businesses that settle along the main street. The NP highlights issues that need to be improved in order to achieve socio-economic sustainability: increased public safety, increased programming for children, and promotion of the Hintonburg commercial area.[vii]

According to the Community Design Plan, 47% of the land in Hintonburg is residential, and only 8% is commercial and office space. The large majority of the latter is located along Wellington Street, where 40% of the land use is commercial and office space. Approximately 13 662 people lived within the borders of this case study in 2006. The “number of dwelling units is almost evenly split between the areas north and south of mainstreet.” The CDP also states that, compared to the City, the community has lower unemployment rates, two times the number of people cycle to work, and there is a smaller income gap. The CDP discusses the projected growth in the community, and provides design goals to manage intensification and ensure that new developments fit the community.[viii]

View of Wellington Street West from Fairmont Avenue looking southwest towards Irving Avenue. The Windmill development, The Eddy, is seen in construction on the left. Photo: Stephanie Elliott 2014.

Cultural sustainability: The Neighbourhood Plan emphasizes the importance of arts and culture in the neighbourhood, and aims to re-brand Hintonburg as a centre for these activities in the City. In both the general text and in “Appendix 4,” the authors list the numerous festivals, events, and initiatives hosted by the HCA to include all community members. The NP also recommends further arts and culture efforts, including the adaptation of historic properties for artistic or cultural uses; creating space for public art; and promotion of community programming and events. The CDP does not directly address cultural sustainability, but the idea of maintaining the neighbourhood character and encouraging its development is present throughout the document. It is included in the design goals by encouraging sensitive intensification that works with the physical fabric of the built environment, as well as ensuring there are public spaces for daily use.[ix]

MEASUREMENT

Impact of Intensification on Heritage Value: Due to the commitment of the community to adaptive reuse, the major built heritage features of the neighbourhood are still intact and performing either commercial, service or residential functions. Most of the intensification projects are integrating with the existing fabric sensitively, as in the case of the École Sacré-Cœur, or are replacing buildings that do not contribute to the heritage value of the community, as in the case of Windmill’s Eddy Development at the corner of Wellington and Irving. Both types of development are being encouraged and required to submit designs which complement the surrounding character; for example, low elevations at the street, and somewhat taller towers in the rear of the properties.[x]

The former École Sacré-Cœur is an award-winning adaptive use project. Infill condos built to the rear of the main building can be seen to the bottom left (19 Melrose Avenue). Photo: Stephanie Elliott 2014.

Walkability, bikeability, and transit availability: “Walk Score”, a website that measures the walkability, bikeability, and transit availability in a community, lists scores for Kitchissippi, the City of Ottawa Ward that contains Hintonburg, Mechanicsville and Wellington West. Kitchissippi has a Walk Score of 94, a Transit Score of 84 and a Bike Score of 100.[xi]Adjusting for the study area of this paper, however, the Walk Score may be somewhat diminished. Hintonburg still does not have a major supermarket, as was highlighted in the Neighbourhood Plan and confirmed by a current resident,[xii] while Walk Score’s analysis includes stores that are west of Holland, in the Wellington West neighbourhood. Likewise, the Bike Score needs adjustment. According to residents and the city in the NP and the CDP, dedicated and shared bike lanes do not yet exist, however Walk Score states, “there are excellent bike lanes.”[xiii] Despite these adjustments, Hintonburg can still be said to have high walkability and moderately high bikeability.

Community sustainability: Catalina Turco’s “Pragmatic List of Domains and Dimensions of Community Sustainability,” developed in her 2009 article, provides a measurement framework for determining the sustainability of a community.[xiv] Turco’s List (Table 1) presents six domains and twenty-eight dimensions of a sustainable community. Using these categories, Turco conducted surveys in three UK towns to discover how residents value these domains, their opinions of them. Since there has been so much community input in the Neighbourhood Plan and the Community Design Plan for Hintonburg, these documents can be applied to Turco’s framework to assess the Hintonburg’s sustainability.

- “Local Economy & Jobs” relates to the strong commercial centre running along Wellington Street West, and extending slightly outwards from this central line. While the entire population of Hintonburg cannot work on this street, many do, and it is convenient for people to access their jobs outside the neighbourhood due to the “excellent transit” linking them with the rest of Ottawa. Since the community encourages independent businesses, residents regularly patronise and promote them. There are social programs that offer training, such as the John and Jane schools for first-time offenders, and the Landlords School to help improve the rental properties in the area. House prices have steadily risen over the last twenty years, as demonstrated in “Appendix 1” of the NP, but the CDP has committed the to maintaining a lower price point in order to avoid gentrification.[xv]

- “Local Community” is emphasized throughout both the NP and the CDP. The community participated in over 100 consultations throughout the creation of both documents, and continue to do so through community groups. The many social initiatives to help reduce instances of illegal behaviour have been extremely successful. Unfortunately, traffic and personal safety goals have not been attained. The community is made up of a diverse ethnic, linguistic, and economic population. The large majority of residents have not moved within the last year, and just under half of the population have been in the community for at least the past five years.[xvi]

- “Local Environment & Natural Resources” is not well addressed in the NP and CDP. Energy use reduction is primarily discussed in the NP and the CDP as related to transportation. “Appendix 12” reflects this, demonstrating that only half of the population owns cars. Water use was not discussed in the Hintonburg documents. Nor were recycling and waste removal, however Ottawa’s Waste Management system of garbage, recycling, and green bins applies in this neighbourhood.[xvii]

- “Local Area & Housing Conditions” is discussed in the “Housing and Housing Stock” section of the NP. “Hintonburg…offers a range of housing options,” including traditional homes and apartments, “as well as rooming houses and social and supportive housing” The community “support[s] the renovation and improvement of homes, and the enforcement of property standards.” The community is proud of the diversity of homes and services incorporated into their area. Green space within the community is a high priority for residents, reflected in the design goals that stress the necessity of green space in new developments.[xviii]

- “Local Services & Facilities” are points of pride for the Hintonburg community. There are currently ten public elementary and middle schools, and one high school in the area, however there is no primary medical service in the study area. The community boasts a large number of accessible facilities and services, which are extensively listed in “Appendix 8.” Public transportation in the area is convenient, and links well with the rest of Ottawa.[xix]

- Finally, “Local Governance” plays strongly in this community. Participation in the NP and CDP processes demonstrates the community’s desire to be involved in the development of their neighbourhood, and the fact that many of the social programs in the neighbourhood have been resident-developed demonstrates that they are willing to work to improve services in their area.

Based on Turco’s framework, Hintonburg is a strong candidate for the title of a sustainable community. The neighbourhood performs poorly on only five of the twenty-eight dimensions of a sustainable community. With the recent implementation of the CDP, these dimensions have great potential to improve.

- [i] Wellington Street West is referred to by its original name, Richmond Road, in historical contexts. The borders outlined here (i.e. stopping at Holland Ave on the west side) reflect both the historic village boundaries and the current division between Hintonburg and the Wellington West community. Likewise, I do not include Mechanicsville in this study, although it is included in the Neighbourhood Plan. This is because information from Mechanicsville is difficult to obtain, their community association was not actively involved in the creation of the Neighbourhood Plan, and because the community is physically cut off from Hintonburg by Scott Street and the Transitway.

- [ii] John Leaning, 2003. Hintonburg and Mechanicsville: A Narrative History. Ottawa, ON: Hintonburg Community Association, 6, 20, 21, 26-31, 7, 32, 38.

- [iii] Leaning, 48. Service increases: The CPR round house was built in 1911 at Somerset and Bayswater, the Église St. François d’Assise had to be rebuilt larger in 1915 to accommodate the influx of Francophones after the fire, the Grace Hospital was built in 1922, the Parkdale Market opened in 1924, and the Parkdale United Church is established in 1925.

- [iv] Leaning, 20.; Jennifer Roddick, 1978. “LACAC Notes.” Heritage Ottawa Newsletter. 6(4): p. 1.; www.banfieldagency.com/contact/.; City of Ottawa, 2014. “Recent Designations.” City of Ottawa. www.ottawa.ca.; HCA, No date. “Hintonburg Walking Tour.” Hintonburg Community Association. www.hintonburg.com.; City of Ottawa, 2011. “2011 Winners.” City of Ottawa.; http://theurbanelement.ca; www.fuelyouth.com.

- [v] An interesting side note of history repeating itself: from the 1890s onwards, according to Leaning, “[a]fter streetcars, the bicycle was the most popular means of wheeled transportation, as is evidenced from the records of pedestrians’ complaints and accidents. There were even suggestions that bicycles should have their own roads, to avoid numerous accidents.” Leaning, 20.

- [vi] City of Ottawa, 2010. Hintonburg/Mechanicsville Neighbourhood Plan, 84.; City of Ottawa, 2013. The Wellington Street West Community Design Plan, p. 20, 22, 23.; City of Ottawa, 2010, 64.

- [vii] City of Ottawa, 2010, 43.

- [viii] City of Ottawa, 2013, 20, 18, 36-48. Hintonburg accounts for “about 73% of community residents” 73% of 18 715 in the greater Wellington West community.

- [ix] City of Ottawa, 2010, 32. City of Ottawa, 2013, 38, 36.

- [x] In August 2013, a proposal by Tega Developments for an 18 storey and 8 storey mixed use building on a 2 or 3 storey podium at 233 Armstrong was rejected by City Council for not complying with the recently approved CDP for the area. The proposed site has zoning for only 8 storeys. This is viewed by the community as a success, and demonstrates the City’s commitment to the CDP in this area. HCA, 2014. “Hintonburg Development Watch.” Hintonburg Community Association. www.hintonburg.com/devwatch.html.

- [xi] The website determines its scores by analyzing “hundreds of walking routes to nearby amenities.” Points are awarded or docked depending on how far those amenities are from the central address, up to a 30-minute walk away. They also account for “population density and road metrics such as block length and intersection density.” Walk Score takes similar approaches for measuring Bike Scores and Transit Scores. Walk Score, 2014. “Walker’s Paradise: Kitchissippi, Ottawa.” Walk Score. www.walkscore.com.

- [xii] City of Ottawa. 2010, 55.; Text conversation with Hintonburg resident Beverly Hinterhoeller, Nov. 21, 2014. “There’s the Giant Tiger … and there is the Metro, but it’s closer to Westboro than Hintonburg. I think that it’s technically in Wellington West?” (12:31-12:32pm). “Accurate” (12:34pm) that there are no grocery stores east of Holland.

- [xiii] Walk Score, 2014.

- [xiv] Catalina Turco, 2009. “In the Quest of Sustainable Communities: A Theoretical Framework to Assess the Impact of Urban Regeneration,” in Tsenkova, Sasha (ed.) Planning Sustainable Communities: Diversity of Approaches and Implementation Challenges. Calgary: University of Calgary: pp. 37-66.

- [xv] City of Ottawa, 2010, 12-13.; Walk Score, 2014.; City of Ottawa, 2010, 12-13, 123.

- [xvi] City of Ottawa, 2010, 62, 113-114.

- [xvii] Ibid, 133.

- [xviii] Ibid, 43-44.; City of Ottawa, 2013, 84-94.

- [xix] City of Ottawa, 2010, 125.

SOURCES

Book and book chapters

- Leaning, John. 2003. Hintonburg and Mechanicsville: A Narrative History. Ottawa, ON:Hintonburg Community Association.

- Turco, Catalina. 2009. “In the Quest of Sustainable Communities: A Theoretical Framework to Assess the Impact of Urban Regeneration,” in Tsenkova, Sasha (ed.) Planning Sustainable Communities: Diversity of Approaches and Implementation Challenges. Calgary: University of Calgary: pp. 37-66. Retrieved Nov. 22, 2014 from http://www.ucalgary.ca/cities/files/cities/SUSTAINABLE_COMMUNITIES.pdf.

Policy documents

- City of Ottawa. 2010. The Mechanicsville/Hintonburg Neighbourhood Plan. Retrieved Nov. 15, 2014 from http://ottawa.ca/calendar/ottawa/citycouncil/occ/2010/02-24/pec/10%20-%20ACS2010-ICS-CSS-0002%20DOCUMENT%202%20%20EN%20Vars.pdf.

- City of Ottawa. 2013. The Wellington Street West Community Design Plan. Retrieved Nov. 17, 2014 from http://documents.ottawa.ca/sites/documents.ottawa.ca/files/documents/cap140039.pdf.

Websites

- Banfield- Seguin Ltd. 2014. “Contact.” Banfield-Seguin Ltd. Retrieved Nov. 21, 2014 from http://www.banfieldagency.com/contact/.

- City of Ottawa. 2011. “2011 Winners.” City of Ottawa. Retrieved Nov. 22, 2014 from http://ottawa.ca/en/city-hall/planning-and-development/built-heritage/2011-winners.

- City of Ottawa. 2014. “Recent Designations.” City of Ottawa. Retrieved Nov. 22, 2014 from http://ottawa.ca/en/city-hall/planning-and-development/built-heritage/recent-designations.

- Fuel Youth Engagement. 2014. “About.” Fuel Youth Engagement. Retrieved Nov. 22, 2014 from http://www.fuelyouth.com/about/.

- HCA. No date. “Hintonburg Walking Tour.” Hintonburg Community Association. Retrieved Nov. 21, 2014 from www.hintonburg.com/walking-tour.html.

- HCA. 2014. “Hintonburg Development Watch. Hintonburg Community Association. Retrieved Nov. 22, 2014 from www.hintonburg.com/devwatch.html.

- Roddick, Jennifer. 1978. “LACAC Notes.” Heritage Ottawa Newsletter 6(4): p. 1. Retrieved from http://heritageottawa.org/sites/default/files/newsletter-pdfs/HerOttNews_1978_05.pdf.

- The Urban Element. No Date. “About.” The Urban Element. Retrieved Nov. 22, 2014 from http://theurbanelement.ca/#/home.

- Walk Score. 2014. “Walker’s Paradise: Kitchissippi, Ottawa” Walk Score. Retrieved Nov. 21, 2014 from www.walkscore.com/score/hintonburg-ottawa.