Urban Campuses and Sustainable Communities: Red River College’s Rehabilitation of the Former Union Bank Tower, Winnipeg, MB.

Case Study prepared by Kevin Complido, Carleton University.

Keywords — Urban Conservation; Mixed-Use Development; Socio-Cultural Sustainability; Historic Urban Landscape; Winnipeg

L E S S O N S L E A R N E D

The Red River College [RRC] demonstrates how to shape sustainable communities through their urban campus initiatives and heritage conservation in The Exchange District, Winnipeg. Building off of their first major Exchange project, the now-named Roblin Centre, saw RRC re-develop a cluster of existing buildings using architectural conservation and sustainability principles to rehabilitate the heritage block into the headquarters of their Exchange Campus.

The success of Roblin as a revitalization effort helped to lay the ideological groundwork for RRC’s further expansion projects in The Exchange. It prompted them to be more ambitious in taking on one of the district’s critical structures, officially designated as the ‘Former Union Bank Building and Annex National Historic Site’ [UBB] (Parks Canada, n.d.b). RRC’s choice to redevelop this prominent building into what has since been dubbed the Paterson GlobalFoods Institute [PGFI; Paterson], shows their commitment to being a leader in developing sustainably in the downtown. Through the renewal of the historic monument, it reasserted this once proud symbol turned-deserted-tower into an example of conservation stewardship’s role in elevating/revitalizing urban space.

The cooperation of private and public sectors plays a key role in the project’s success. The ambition embedded in the project required all parties to recognize the stakes at risk of an unsuccessful publicly displayed project. The early success of the project so far will be argued as having a pivotal role in overall positive growth that The Exchange is witnessing. This is visible in the growing vitality of the district, which Paterson is seen as contributing holistically to in it’s contributions to densification, heritage renewal, and the richness of services and amenities seen at the Exchange.

Because of the relative newness of the project, the research has been guided by a look at assessments of Roblin, heritage significance of the building and its context, and role of the building/RRC in the greater Downtown BIZ/redevelopment efforts; as well as the author’s experience of UBB/The Exchange that takes into account a perspective that looks beyond the prevalent literature and analyses.

P R E S E N T A T I O N

As part of the scope of the case study, a presentation was given which briefly outlined the key points and findings of the search. It serves as a condensed version of the case study’s findings, complete with embedded tables, illustrations, and imagery.

The presentation, given in class on November the 21st, 2017, can be accessed below:

Presentation: Heritage District Revitalization

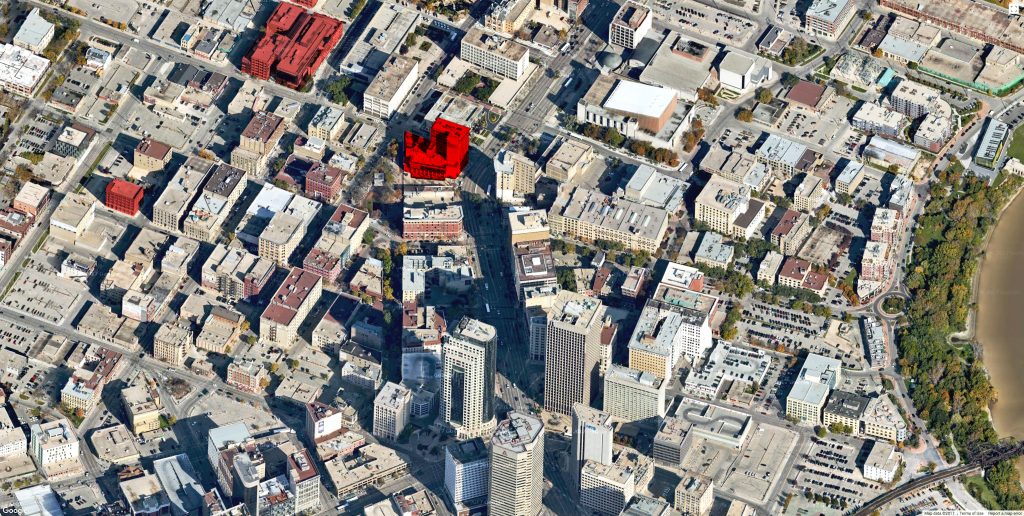

Figure 1: 45° Image of Winnipeg’s Exchange District NHS. Red River College owned spaces in red, Paterson GlobalFoods Institute in bright red. [ Photo: modified by author from Google Maps ]

D E S C R I P T I O N

Background

Located prominently along Main Street, in Winnipeg’s historic Exchange District National Historic Site [NHS], is the former Union Bank Building/Tower (also an NHS), which today bears the name Red River College’s Paterson theGlobalFoods Institute [‘PGFI’; ‘Paterson’]. Primarily owned by and operating as a bank for the majority of its 100+ year history, the building lay vacant for some years before the RRC acquired the property with the intention of converting it for the ever-expanding offering of RRC’s programs (Prairie Architects, n.d.). The approach would be informed by RRC’s first major Exchange intervention, the Roblin Centre, or (then) Princess Street Campus, completed in 2002. This project saw the sustainably focused conversion/conservation of a block of heritage buildings as the RRC’s main downtown campus at the time (Cibinel Architects, n.d.), which they would soon quickly outgrow.

Officially opening its doors in 2013, Paterson’s primary occupants are the RRC’s School of Hospitality and Culinary Arts [SHCA], as well as 106 student residence units which occupy the rehabilitated tower of the building (Prairie, n.d.). The ground levels are occupied by the SHCA and associated services and facilities. Intended to engage the public by giving the culinary students hands-on experience, the School operates and provides short-order and more upscale food services for a public cafeteria, ‘The Culinary Exchange’, and restaurant, ‘Jane’s’ (RRC, ‘blogs.rrc.ca/edc/’).

Significance

The programs mentioned above expand upon the facilities and offerings of the RRC in the form of an emphasis on food, hospitality, education, and housing. All these programmatic additions have helped play a key role in leading sustainably based development through a mixed-use approach that has helped the urban revitalization of The Exchange.

The ideologies at the heart of Paterson’s coming to being are emblematic of RRC’s role in the multifaceted social, cultural, and economic sustainability efforts that are at the forefront of The Exchange’s renewed character. They’re representative of a growing trend, which is seeing higher learning institutions having an active and often leading hand in shaping city development (Peters, 2017; TEDxTalks, 2011; Green et al., 2013). Paterson’s contributions to this dialogue include that it stands as a prominent symbol for built heritage conservation in the eyes of the public, it is a visible sign of changing times along its very prominent location on Main Street. Whereas the Roblin Centre could be seen as more insular

T I M E L I N E

| Context | |

| 1870s – 1910s |

The City of Winnipeg becomes incorporated in 1873, and grows from a population of just under 2000, to 160,000 by 1916 (Goldsborough, 2017; Turner, 2014, 19). |

| Development of the Exchange District takes off between 1880-1913 (Parks, n.d.a.) | |

| As Intended Function (86 years) (Parks, n.d.b.) | |

| 1906 | Union Bank Building constructed. Operates as a bank. |

| 1920 | Savings Annex added |

| 1925 | Serves as primary branch of the Royal Bank of Canada in Winnipeg (then the amalgamated Union Bank) in Winnipeg until 1966. |

| Vacant (17 years) (Kives, 2009; Parks, n.d.a., n.d.b; Cibinel, n.d.) | |

| 1992 | Building vacated. Still operated primarily as a bank until this time. |

| 1996 | Union Bank Building designated a Class 1 National Historic Site |

| 1997 | The Exchange District designated a National Historic Site |

| 2003 | RRC’s Roblin Centre opens (then called ‘Princess Campus’) |

| Red River College Possession (til present day) (Prairie, n.d.; aashe, 2012; CaGBC, 2017; Eluta.ca, n.d.) | |

| 2009 | Red River College takes ownership of Union Bank Tower |

| 2012 | RRC achieves Sustainability Tracking, Assessment & Rating System (STARS) Silver PGFI awarded ‘Heritage Winnipeg Conservation Award’ |

| 2013 | Union Bank Building renovations completed |

| RRC opens the now named Paterson GlobalFoods Institute | |

| PGFI awarded Heritage Canada Foundation’s ‘Cornerstone Award for Building Heritage’ | |

| 2017 | PGFI awarded LEED Gold for New Construction and Major Renovations 1.0 [for more, see fig 6] |

| RRC recognized as: one of Canada’s Greenest Employers, Canada’s Best Diversity Employers, and Manitoba’s Top Employers | |

The sequence of events which lead to the rehabilitation of UBB follows the story of the downtown’s developmental history and renewal. Winnipeg, in its earlier years as an incorporated city, proliferated in parallel to the role it played as a transportation hub (rail in particular) and the development of the West (Turner, 2014). The UBB, completed in 1906, was reflective of this energy and optimism: it was the tallest steel structure in Canada at the time (Turner, 36), and became an essential symbol of Winnipeg’s role in the economy of the West (Parks, n.d.b).

Winnipeg’s role as a national power would later go on to be diminished by other global factors, and so development slowed to a comparative crawl (Turner, 2016). The UBB maintained operations as the Union Bank, then was acquired by the Royal Bank of Canada, and after 86 years of tenure moved out (Parks, n.d.b.). The building lay vacant for 17 years before it was acquired by the RRC, who adaptively re-used the tower, building, and annex into a mixed-use space. Having re-opened in 2013 as the Paterson GlobalFoods Institute, named after a private company and stakeholder of the project, it is now primarily educational, and housing programs (Prairie, n.d.; Kives, 2009).

Sources: CentreVenture (n.d.).; Cibinel Architects (n.d.); Parks Canada (n.d.a., n.d.b.); Prairie Architects (n.d.); Kives (2009); Turner (2014).

S T A K E H O L D E R S

| Organizations + Donors |

Government of Canada |

| Province of Manitoba | |

| City of Winnipeg | |

| Centre Venture Development Corporation — “an arms-length agency of the City of Winnipeg” (n.d.) | |

| The Winnipeg Foundation — a community non-profit | |

| Paterson GlobalFoods Inc. — a private company | |

| Users / Owners | Red River College |

| RRC: ‘The School of Hospitality and Culinary Arts’ | |

| RRC: ‘The Culinary Exchange’ — a public cafeteria, food made by culinary students) | |

| RRC: ‘Jane’s’ — a ‘student-run’ restaurant (source) | |

| RRC: Student residences — 106 units, of 1 or 2 bedrooms | |

| Consultants | Prairie Architects Inc — Prime Consultants |

Of note are the contributions by CentreVenture and the Winnipeg Foundation, which are indications of some of the underlying principles present in the programmatic aspirations of the project. CentreVenture is a quasi-private/public group that calls themselves an ‘arms-length City of Winnipeg organization’ whose “mandate is to provide leadership in planning, development, coordination, and implementation of projects and activities in the downtown” (CentreVenture, n.d., ‘About’ section). The Winnipeg Foundation, on the other hand, is a non-profit organization that has a tendency to donate to projects that contribute to ‘community needs’ (n.d.), and whoin 2016 allocated 4% of their grants to Heritage projects, and 15% to Education (2017). Both investments indicate the more significant role the project was viewed as having in its potential to contributing to the city beyond simple post-secondary spaces (TEDxTalks, 2011).

Paterson, in its current form, is the result of multifaceted collaborative effort spanning public and private stakeholders. Each branch of government provided significant funding for the project, with the federal contribution has been part of the economic-stimulus plan, and with private groups and the RRC themselves rounding out the rest of the initial costs (Kives, 2009). Whereas organizations can sometimes feel at odds in the development of a project, it appears that in the contributive efforts of a mix of public, private and non-profit organizations, that many perspectives saw the potential for this project to play a more significant role beyond its primary functions.

Design-wise, the project was lead by Prairie Architects, a local firm that is mainly known for their commitment to LEED and sustainability, reflecting on RRC’s environmental sustainability goals.

Sources: Prairie Architects (n.d.); Kives (2009); CentreVenture (n.d.); RRC (n.d., [blogs.rrc.ca/culex/])

Figure 2: Newly constructed Union Bank Building seen far right, situated along Main Street, 1907. [Photo: Archives of MB, in Turner (2014, 1)]

H E R I T A G E

Historically, the UBB has been a defining symbol of Winnipeg’s developmental heritage (Parks Canada, n.d.b.). Key aspects that define its underlying character are its location and stature as a major landmark in the historic urban landscape. It’s found at the apex of a prominent bend in Main Street; found opposite another Exchange NHS landmark, the Confederation Building (Parks, n.d.b.); at the time of construction was Winnipeg’s first skyscraper, and the tallest steel structure in Canada (Turner, 2014, 36); adjacent to Old Market Square; and next door to City Hall.

Urban Heritage

Given the downtown context, the physical environment’s heritage is primarily urban, but the city’s natural qualities do guide underlying character-defining frameworks for the site. As seen in fig.1, the grid and primary thoroughfares of The Exchange and area are shaped by the winding contours of the river. This influence lends to a unique assortment of lot shapes and building forms, reflected in the exterior form of Paterson.

Paterson’s, and the Exchange’s proximity to the river are a comfortable 10-minute walk to the Riverfront’s green space. Another 10 minutes brings one to the important recreational area of another NHS, The Forks, at the junction of the two rivers in the city. More human-made leaning landscapes are present in Paterson’s adjacency to Old Market Square, which has become the heart of The Exchange as a favourite summer meeting grounds, including ‘The Cube’ an iconic landmark of a performance space, landscaped seating, and grassed square.

Cultural Heritage

Today, Paterson’s heritage exterior is relatively intact compared to its original form which “illustrates many of the architectural and engineering developments of its time … follow[ing] the classical palazzo model … [built on an] innovative floating platform base” (Parks, n.d.b). The building was/is part of the “majestic ‘Bankers’ Row’ that featured some 20 monuments to money” (Turner, 2014, 11), a prominent landmark among those in the city’s historic urban landscape. It’s described in its CHRP entry as “the towering gateway to Winnipeg’s historic financial district … an important civic and corporate symbol” (Parks, n.d.b) for Winnipeg and the Union Bank’s role in “the most economically aggressive city in North America” at the time (Albo, in Turner, 2014, 11). Today, it’s believed to be the nation’s oldest surviving steel and concrete reinforced structure” (Turner, 2014, 36-127).

As one of the Exchange’s landmark buildings, Paterson has served as a kind of billboard of growth and development throughout its history (even literally, in its defining signage which stands high above the landscape [see and compare figs. 2 & 3]). Its relative height compared to its surroundings, is further accentuated in the way that it’s position along Main literally points traffic to its location from either direction of the street.

As a billboard for contemporary development, Paterson, along with the Roblin Centre, stand as clear markers in the landscape of adaptive re-use in Winnipeg, incorporating “the integration of historic urban area conservation, management and planning strategies into local development processes and urban planning” (UNESCO, Annex 1). This consideration is an essential factor in the protection of cultural heritage, and as a resource for sustainable development and quality of life (Council of Europe, 2005, 1).

![Paterson GlobalFoods Institute and Old Market Square [@gmerk]](http://sustainableheritagecasestudies.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Complido-RRC-and-OMS-instgram-gmerk-768x1024.jpg)

Figure 3: View of Paterson in relation to Old Market Square (OMS).

Visible are Paterson’s student residences tower, new culinary institute interventions, and building’s relationship to significant surrounding urban + cultural spaces. [Photo: @gmerk, Instagram]

S U S T A I N A B I L I T Y

Due to the Paterson project’s relative newness, in 2017 little critical academic literature on Paterson was located. This is especially true in regards to sustainability, where little of what seems accessible isn’t in some way potentially subjectively marketed or reported by the RRC. Still, these reports will be treated as though they were objective (for a further note on analysis methodology, see Endnote 1).

The following table summarizes some assessed contributions of RRC and Paterson’s interventions to three dimensions of sustainability:

![Sustainability at the Paterson GlobalFoods Institute [by Author]](http://sustainableheritagecasestudies.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Complido-RRC-PGFI-Sustainability-author-1024x473.png)

Figure 4: Table — Paterson GlobalFoods Institute and Sustainability

This table organizes some of the key ideas of sustainability at play in the case study, sorted loosely around the three pillars of sustainability. Where table cells merge into other columns demonstrates how an approach can be seen as contributing to multiple dimensions of sustainability. [Sources: 1. CaGBC (2017) // 2. Prairie (n.d.) // 3. RRC (n.d., /redgreen) // 4. Peters (2017), Rodwell (2003) // 5. CentreVenture (n.d.)]

While the environmental and heritage sustainability perspectives of RRC/PGFI are no doubt validated in available sources, I wish that later literature might merit their contributions holistically, both in their impact to the city, and sustainability in a broader sense. I say this from a perspective that comes from being an architecture student of the city, nearby resident, and worker of The Exchange: PGFI/RRC are key players in promoting an overall sustainability of the surrounding community. So while their individual contributions might be difficult to pin down, when we view the opposite, it’s difficult to exclude their influence on the Exchange’s revitalization as a whole, so future perspectives may wish to consider.

A Holistic View of Sustainability

Using their mixed-use approach to the overall undertaking at Paterson, sustainability is achieved in a variety of ways that attempt to see the concept as understood in a programmatic sense, bearing influence on contributing to more prosperous, socio-cultural and economic offerings on site. These views of sustainability are touched on in the accompanying fig.4 table, which attempts to see individual efforts as contributing to a more dimensional look of sustainability. For example, because of the role-model like consequence Paterson has had in densifying the Exchange through the addition of student housing, Paterson should be considered in more holistic assessments, like CentreVenture’s (see their website). They look at the overall growth of local businesses in the downtown: an argument could be made that the RRC had helped shaped property values, or boost confidence in a reliable customer base.

RRC’s initiatives should also be looked at for it’s contributions to the overall ideological (and practical) ways it’s looking at promoting sustainability within their community. Of particular note is it’s “Office of Sustainability” which has three dedicated staff members involved with the managing and coordinating of important efforts (blogs.rrc.ca/), which shows RRC collaborating with and taking the lead in being proactive in the field.

Paterson’s impact is less represented in terms of socio-cultural and overall economic benefits, but these tie it holistically with the overall current vitality of The Exchange. However, because of the relative difficulty in quantifying the individual contributions in a ‘multiplier effect’ (Stubbs, 2014) (which will be looked at further in Assessments), and the subjectivity of the reverse in attempting to tack on a name to larger recognition, the overall positives may always be difficult to associate with the RRC.

![Jane's, at the Paterson GlobalFoods Institute [Scott, 2014]](http://sustainableheritagecasestudies.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Complido-RRC-PGFI-and-Janes-Scott.jpg)

Figure 5: Interior of Jane’s restaurant, a rehabilitation of the space of the former banking hall. The cooks are culinary students from the RRC. [Photo: Scott, 2014]

M E A S U R E M E N T

The measurements outlined here are reflective of ideas introduced under Sustainability; they are framed to include the initiatives of Paterson GlobalFoods Institute, as well as the founding ideological efforts of the Red River College. RRC, as an institution, is also a significant factor in the overall contributions to sustainability in The Exchange. (Further, see Endnote 1 for a note on analysis methodology)

Assessing Environmental Sustainability

Environmentally, it is documented that RRC + Paterson demonstrate a commitment to sustainable building practices that are considerate of their heritage contexts, with some awards being given in recognition (see awards in timeline; CaGBC, 2017; Eluta.ca, n.d.; Prairie, n.d.).

Framing sustainability directly in the context of LEED, in fig.6, Paterson’s scorecard is analyzed to see what it says about the building. Overall, the score presents a good picture of sustainable efforts, but a better score is impeded by its context, given the adaptive re-use, existing building constraints, and urban landscape constrictions. One such example is Credit 1.2 in Materials & Resources, where in order to obtain the point the building reuse must “maintain 95% of existing walls, floors & roof.” This was likely unachievable given the adaptive re-use of the tower and its conversion from office space to student dorms, which may have made the credit of little gain for the difficulty.

| Figure 6 An Assessment of Paterson GlobalFoods Institute’s LEED Scorecard |

||

|

LEED |

Rating — LEED Canada Gold for New Construction and Major Renovations 1.0 (40/70 possible points. Gold assessed as 39-51 points) | |

| Project Size — 9868 m2. | ||

| Project + Owner Type — Mixed-use. University/College. | ||

| Certification Date — February 9th, 2017. | ||

| LEED Category | LEED Score out of total poss. pts in catg. |

Case Study Author’s Commentary |

| Sustainable Sites | 4 / 5 | Given the nature of the points, all fair considering context |

| Water Efficiency | 4 / 5 | Only missed ‘Innovative Wastewater Technologies’ |

| Energy & Atmosphere | 11 / 17 | 8/10 score for ‘Optimize Energy Performance’. No points given for ‘Renewable Energy’ |

| Materials & Resources | 7 / 14 | No points for ‘Resource Reuse’. Scores low for general resource recyclability. |

| Indoor Environmental Quality | 8 / 15 | Points missed seem reasonable, considering adaptive re-use constraints. |

| Innovation & Design Process | 5 / 5 | No room for improvement, per LEED |

Sustainability in the Bigger Picture at RRC/PGFI

Sustainability at the RRC/PGFI, beyond existing assessments of the primary environmental and physical heritage dimensions, should be seen for their merit in implementing it and other workplace culture initiatives as core, ideological values (Eluta.ca, n.d.). Their Office of Sustainability keeps a dedicated blog, ‘Red Goes Green’ (blogs.rrc.ca/redgreen/) which goes a long way in seeing how RRC currently implements sustainability in their organization as a matter of principle, and responsibility.

When we view this collection of blog posts, and consider Paterson overall in the framework of their STARS Silver self-assessment of 2012, we begin to see RRC’s commitment to integrating sustainability as a critical operational directive. The college sees it as something they must always strive to improve on, as a list of goals with which to measure their successes. If in 2012, they had not scored points in a particular credit, they have likely since addressed that. One example is in their missed Transportation credits for ‘Bicycle Sharing’; ‘Facilities for Bicyclists’; and ‘Bicycle Plan’ (AASHE, 2012); all of which were since addressed in their RRC Transportation Plan (blogs.rrc.ca/redgreen/).

RRC’s sustainability initiates continue to be seen as having effects in the larger scale of downtown civic development and cultural well-being as a whole. As in the ideas brought up by Peters (2017), and in Levy’s TEDx talk (2011), the role of the urban campus is seen as leading development initiatives. In his article, Stubbs (2004) talks about the ‘multiplier effect,’ which often involves a difficulty in quantifying and formally assessing sustainability initiatives. When viewed in the scope of The Exchange District’s overall revitalization, I think that there’s an opportunity to see the same kind of thinking of a more qualitative form of measurement in assessing RRC’s successes (a table of possible measurements below, as fig.7). When we view their efforts through this lens, it becomes much easier to understand that the contributions RRC and the Paterson GlobalFoods Institute have had in promoting positive, sustainability development, in a variety of forms.

| Figure 7 The following are other possible means of assessing the Paterson project and its influence, which could be pursued, in the spirit of RRC’s continuing improvement. They are formulated as questions, for which specific data and measures of surveying would have to be defined (based on ideas in Stubbs, 2004 and de Silva and Henderson, 2011) |

|

| RRC Culture | Grads: Where do the Culinary and Hospitality Grads go on to work? |

| Does Paterson give more equitable/livable options? Where are other non-Winnipeg residences of the RRC living? | |

| What number of Exchange residents are associated with the RRC? Is densification being promoted? | |

| Office of Sustainability: What sustainable practices could be seen as a direct result of their involvement? | |

| Economic Indicators | How have Exchange property values changed over time? Are there are correlations to RRC’s interventions? |

| CentreVenture Annual Report data: Looking to this information/data as being a holistic indicator of growth that RRC would have contributed to | |

| Influence Indicators | Are there any projects that reference RRC’s efforts as models? |

| How has the number of Exchange rehabilitation projects changed over time? | |

| Socio-cultural Indicators | A survey that asks local businesses: how many are regulars? |

| A survey that asks Paterson’s food offerings: what brought you here? Work break? Student? Exchange resident? | |

| Implementation of a student discount for local businesses: related impacts? | |

| Related measurements on the livability or walkability of The Exchange? | |

R E F E R E N C E S

Books / Book Chapters / Journal Articles

- Carroon, J. (2010).Sustainable Preservation: Greening Existing Buildings. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Green, A. et al, 2013, “Living Heritage: Universities as Anchor Institutions in Sustainable Communities,” International Journal of Heritage and Sustainable Development, 3.1: pp. 7-19, http://ijhsd.greenlines-institute.org/volumes/2013/IJHSD_2013_V03_01_Green_7_19.pdf.

- Brand, S. (2012). How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They’re Built. London: Penguin Books.

- Rodwell, D. (2003). “Sustainability and the Holistic Approach to the Conservation of Historic Cities,” Journal of Architectural Conservation1: 58-73.

- Ross, S. (2006). Saving Heritage is Key to Sustainable Development. Heritage: 6-11.

- Turner, R. (2014). City Beautiful: How Architecture Shaped Winnipeg’s DNA. Winnipeg, MB: Winnipeg Free Press.

Policies, Reports and Official Designations

- The Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education. (2012, April 27). Red River College. STARS, a program of aashe. Retrieved from https://stars.aashe.org/institutions/red-river-college-mb/report/2012-04-27/.

- Canada Green Building Council. (2017, February 9). LEED Project Profiles: Paterson GlobalFoods Institute and Student Residence. Retrieved from http://leed.cagbc.org/LEED/projectprofile_EN.aspx.

- Council of Europe (2005). Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society, (Faro Convention), http://conventions.coe.int/Treaty/en/Treaties/Html/199.htm.

- Parks Canada. (n.d.a). Exchange District National Historic Site of Canada. Retrieved October 30, 2017, from http://www.historicplaces.ca/en/rep-reg/place-lieu.aspx?id=1208

- Parks Canada. (n.d.b). Former Union Bank Building and Annex National Historic Site of Canada. Retrieved October 30, 2017, from http://www.historicplaces.ca/en/rep-reg/place-lieu.aspx?id=1136

- (2011). Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape. UNESCO General Conference 36C: Annex, 5-12. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0021/002110/211094e.pdf.

Newspaper Articles

- Bellamy, B. (2011, November 03). Downtown’s Status Symbol. Winnipeg Free Press. Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.proxy.library.carleton.ca/docview/375280424/E3B300BDF5F24E6FPQ/1?accountid=9894

- Kives, B. (2009, October 16). Heritage Reborn: Union Bank Tower to Become Multi-purpose Red River College Facility. Winnipeg Free Press. Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.proxy.library.carleton.ca/docview/752216296?pq-origsite=summon

- McNeill, M. (2011, April 25). Heritage makeover starts to emerge in downtown. Winnipeg Free Press. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/863 115289?accountid=9894

Online Resources (Websites, Other Media)

- CentreVenture (n.d.). CentreVenture Development Corporation. Retrieved November 20, 2017 from http://www.centreventure.com/

- Cibinel Architecture Ltd. (n.d.). Red River College Roblin Centre. Retrieved November 20, 2017 from http://cibinel.com/project/red-river-college-2/

- Eluta.ca. (n.d.). Red River College. Mediacorp Canada Inc. Retrieved December 10, 2017 from http://content.eluta.ca/top-employer-red-river-college

- Goldsborough, G. (2016, November 29). Historic Sites of Manitoba: Union Bank Building (504 Main Street, Winnipeg). Retrieved from http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/sites/unionbankbuilding.shtml

- Goldsborough, G. (2017, October 25). Manitoba Communities: Winnipeg (City). Retrieved from http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/municipalities/winnipeg.shtml.

- Peters, D. (2017, October 4). Universities are helping to shape city development. University Affairs. Retrieved October 29, 2017, from http://www.universityaffairs.ca/features/feature-article/universities-playing-big-role-development-cities/

- Prairie Architects Inc. (n.d.). Educational Buildings: Red River College Culinary Arts Student Housing. Retrieved October 29, 2017, from http://www.prairiearchitects.ca/education?project=Red-River-College-Culinary-Arts-%2B-Student-Housing&id=112

- Red River College. (n.d.a.). Red River College. Retrieved November 20, 2017, from http://www.rrc.ca/

- Red River College. (n.d.b.). STARS. In Red Goes Green Retrieved December 6, 2017 from http://blogs.rrc.ca/redgreen/planning-events/stars/.

- TEDx Talks. (2011, January 5). TEDxRyersonU – Sheldon Levy – Universities as City Builders[Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/6qqQTNR_g-0

- The Winnipeg Foundation. (n.d.). Our Core Mission and Core Values. Retrieved December 10, 2010 from http://www.wpgfdn.org/Portals/0/Uploads/Documents/About-Us/About_Us_-_Mission_and_Core_Values.pdf.

- The Winnipeg Foundation. (2017). 2017 Overview. Retrieved from http://www.wpgfdn.org/Portals/0/Uploads/Documents/About-Us/About_Us_-_Overview_of_The_Winnipeg_Foundation.pdf.

i m a g e l i s t

- Feature Image: Woods, J. (Photographer). (2014, April). Paterson GlobalFoods Institute, formerly Union Bank Building [photgraph]. From City Beautiful: How Architecture Shaped Winnipeg’s DNA, by Randy Turner, Winnipeg, MB: Winnipeg Free Press.

- Figure 1: Google. (n.d.). [45° of Winnipeg’s Exchange District]. Retrieved November 20, 2017, from https://google-developers.appspot.com/maps/documentation/javascript/examples/full/aerial-simple.

- Figure 2: Archives of Manitoba (1907) [photograph]. From City Beautiful: How Architecture Shaped Winnipeg’s DNA, by Randy Turner, Winnipeg, MB: Winnipeg Free Press.

- Figure 3: Merkeley, G. [@gmerk]. (2017, October 24). [Photograph of Old Market Square]. Retrieved from https://www.instagram.com/p/BapWyueg7M8/?taken-by=gmerk.

- Figure 5: Scott, B. (Photographer). (2014, April). RRC Paterson Global Foods Institute Dining Hall [digital image]. Retrieved from http://winnipeglovehate.com/2014/04/09/rrc-paterson-global-foods-institute-dining-hall/

E n d n o t e s

- The sections of Assessment and Sustainability will have some running threads which run into one another, as these topics are being looked at from a self-assessed perspective brought on by the lack of formal materials. The writing and analysis will be based on course readings, research in related topics. (i.e.: literature on the Roblin Centre; RRC’s self-reporting of their overall sustainability initiatives), and personal experience as a resident of Winnipeg (2011-2017), and worker in The Exchange (2015-2016).