OCCUPYING A SUSTAINABLE HISTORIC BUILDING IN TORONTO

Case Study prepared by Olivia Ashton, History & Theory of Architecture, Carleton University

Keywords: Stewardship, Adaptive Reuse, Sustainable Community Planning, Embodied Energy, Passive Survivability, Toronto

LESSONS LEARNED

This case study will examine how the Ontario Heritage Trust (OHT), which embodies and advocates for the protection of both cultural and natural heritage, occupies a heritage office building that demonstrates early sustainable design features. The several misconceptions surrounding old buildings include anything from being considered too drafty to that they require more energy to operate and heat. Perhaps this explains why older buildings are often overlooked when studying green construction because it is believed that new buildings are the way to a sustainable future. However, in retrospect, existing buildings are inherently more energy efficient – thanks to durable materials, operable windows, and natural lighting, to name a few. The adaptive reuse of an existing building, deters demolition, avoiding massive amounts of debris from ending up in landfills, thus decreasing land and air pollution.

When retrofitting an existing historic office building to meet the needs of its occupants today, careful consideration should be taken to not interfere with the inherent qualities of the building. The windows in the Birkbeck Building demonstrate passive survivability, in the sense that they not only allow natural light to flood the interior spaces but provide much needed ventilation to cool the building during summer months (Bubelis, 2009, p.7). These and several other inherent environmental features, which contribute to the heritage building’s embodied energy, are examined in this case study.

When the Birkbeck Building was adapted in 1985-87 as use for the OHT’s headquarters, a minimal intervention approach was used. This approach of minimal intervention stems from the OHT’s core values of promoting and protecting cultural and natural heritage. The OHT – thanks to over 60 years of experience – recognized that the building’s original features served a crucial role in maintaining its energy efficiency. Rather than occupying a new building, the OHT chose a building that incorporated environmental design principles and historical significance. Thus, the OHT presents itself as an organization that promotes the adaptive reuse of existing buildings. Located in the dense downtown core of Toronto, it also encourages sustainable community planning.

PRESENTATION

The following link is a presentation of my case study that occurred on November 28, 2017. The presentation took place at Carleton University for the Heritage Conservation & Sustainability course. It provides a brief overview of the information that will be examined in detail below.

DESCRIPTION

This case study will consider both the physical structure – The Birkbeck Building – and the organization – The Ontario Heritage Trust – that occupies it.

Taylor, D. (Photographer). (2014). The exterior southern façade of the Birkbeck Building at 10 Adelaide Street East in Toronto, Ontario, displays the Edwardian style features [digital image]. Retrieved from https://tayloronhistory.com/2013/12/24/torontos-architectural-gemsthe-birkbeck-building-at-8-10-adelaide-st-east/

Ontario Heritage Trust (Source). (n.d.). The Ontario Heritage Trust’s logo [digital image]. Retrieved from http://www.heritagetrust.on.ca/en/

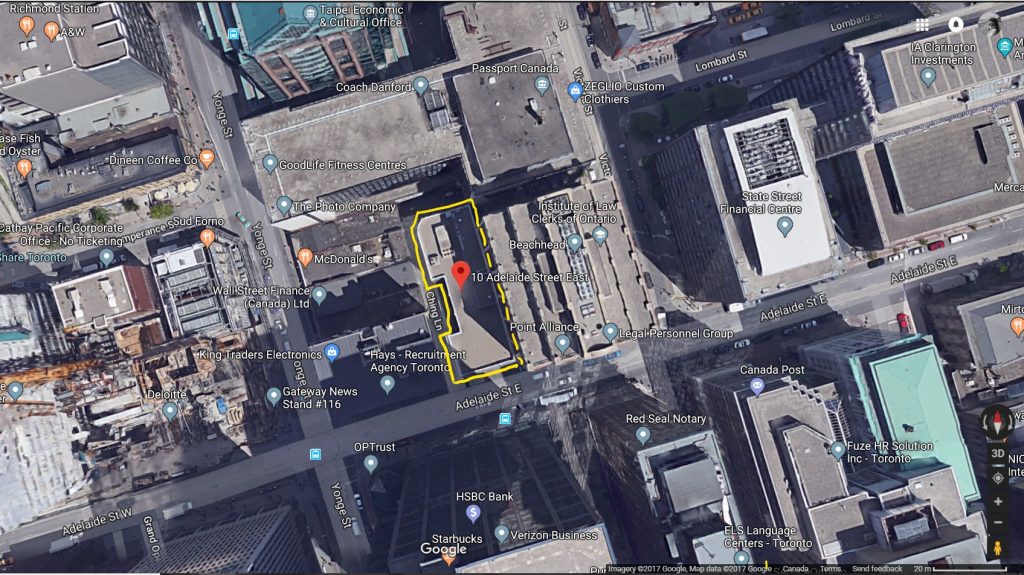

Google Maps (Source). (2017). A context map showing the location of the Birkbeck Building at 10 Adelaide Street East in Toronto, Ontario [digital image]. Retrieved from https://www.google.ca/maps/place/10+Adelaide+St+E,+Toronto,+ON+M5C+1J3/@43.65083,-79.3779981,159m/data=!3m1!1e3!4m5!3m4!1s0x89d4cb32fbf1775b:0x2139844384727ecf!8m2!3d43.650814!4d-79.3779445

Birkbeck Building:

| 1908-10 | Built for the Canadian Birkbeck Investment and Savings Company (Taylor, 2014) |

| 1910-27 | Occupied by the Canadian Birkbeck Investment and Savings Company and its successor, the Canadian Mortgage and Investment Company (Parks Canada, n.d.) |

| 1927 | Sold to the Standard Bank of Canada (Parks Canada, n.d.) |

| 1927-85 | Ownership of the structure passed to several corporations and individuals |

| 1985 | Purchased by the Ontario Heritage Trust (OHT, n.d.) |

| 1985-87 | The Ontario Heritage Trust restores and adapts the four-storey building as office space (Parks Canada, n.d.) |

| 2002 | Restoration of the former banking hall known as The Gallery, which is now an event and conference space |

| 2005-07 | Restoration of the façade in three phases (OHT, n.d.) |

Ontario Heritage Trust:

| 1950s | Initially known as the Archaeological and Historic Sites Board (OHT, 2016) |

| 1967 | The Sites Board was incorporated into the Ontario Heritage Foundation was established (OHT, 2016) |

| 1985-87 | The Ontario Heritage Foundation purchases the Birkbeck Building and rehabilitates the building to use as office space |

| 2005 | The name is changed to Ontario Heritage Trust by an amendment to the Ontario Heritage Act (OHT, 2016) |

STAKEHOLDERS

Birkbeck Building:

Organizations/Owners/Users:

- The Ontario Heritage Trust

- Parks Canada (National Historic Site of Canada in 1986)

- City of Toronto (designated under Part IV of the Ontario Heritage Act in 1976)

- Architectural Conservancy of Ontario (ACO)

The Birkbeck Building is owned and operated by the Trust, however the additional office spaces are rented out to other tenants. One of the other tenants being the Architectural Conservancy of Ontario (ACO). The Birkbeck Building in recognized by the Government of Canada, under federal jurisdiction, as a National Historic Site of Canada. It is also recognized on the Provincial level by the Ontario Heritage Trust and the Municipal level by the City of Toronto.

Ontario Heritage Trust:

Relationships:

- Governments, Municipalities, Indigenous Communities, Conservation Authorities, Land Trusts, Heritage Organizations, Historical Societies, Private Landowners, Tenants, School Boards, and Universities

The OHT is under the jurisdiction of the municipal Government of Ontario. The relationships and partnerships with those mentioned above are crucial in the OHT’s success. More than 60 per cent of the OHT’s funds are raised themselves, while work is supported in part by a government grant. The remainder of their income comes from properties, program fees, and through donors and sponsors (OHT, n.d.). Therefore, the OHT strives to maintain a reputable and creditable reputation with its stakeholders and the public.

HERITAGE

Birkbeck Building:

Cultural heritage:

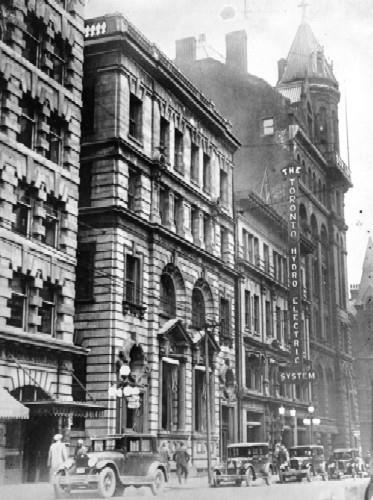

According to Parks Canada, “the Birkbeck Building was designated a national historic site of Canada because it is a good representative example of a transitional building which combined historical style with modern technology” (Parks Canada, n.d.). The building is significant for its Edwardian architectural style with Beaux Arts and Baroque influences. The composition of the street-facing façade is symmetrical. The building’s character-defining features lie mostly in its exterior façade. Combining classical features that include voussoirs, cornices, columns, brackets, and ornate window and door surrounds, with Edwardian and Baroque style elements such as oversized keystones, broken pediments, heavy banding, and volutes, the street-facing façade is reminiscent of Renaissance Palazzo buildings. The unique exterior features include the bull’s-eye windows complete with garland frames above each of the doors, a pair of small hooded cartouches, and several oversized keystones. Following the Great Fire of 1904, a new skyline emerged in Toronto with taller buildings that consisted of modern fire-proofing construction. The building was constructed using durable cast stone and fireproof materials that consisted of a steel frame with porous terracotta tiles as infill.

Unknown (Photographer). (1927). This photo, taken from Adelaide Street East, shows the southern front façade of the Birkbeck Building and the buildings adjacent to it in Toronto, Ontario [digital image]. Retrieved from http://www.historicplaces.ca/en/rep-reg/image-image.aspx?id=19809#i2

The presence of the original occupants can still be felt through the existing stencils of the ‘Canadian Birkbeck’ logo within a laurel wreath (Parks Canada, n.d.).

Mah, S. (Photographer). (2016). The Gallery, located at ground level of the Birkbeck Building, displays several classical elements. Seen here are the crown mouldings, the pilasters, the iron railing on the mezzanine, and the marble staircase [photograph]. Toronto.

Mah, S. (Photographer). (2016). The wood paneling in the oval boardroom of the Birkbeck Building [photograph]. Toronto.

Natural heritage:

The Trust is concerned with protecting wetlands, woodlands, grasslands and geological land formations. “The Trust holds in trust for the people of Ontario a portfolio of more than 160 natural properties, including over 100 properties that are part of the Bruce Trail. Protected land includes the habitats of endangered species, rare Carolinian forests, wetlands, sensitive features of the Oak Ridges Moraine, nature reserves on the Canadian Shield and properties on the spectacular Niagara Escarpment.” (OHT, n.d.) This focus on the natural landscape ensures that all facets of Ontario’s heritage will be conserved.

Cultural heritage:

“The Ontario Heritage Trust holds 27 built heritage sites for the people of Ontario. Eleven of these properties have been designated as National Historic Sites” (OHT, n.d.). The OHT has a direct hand in conservation by implementing several educational and communications programs, that include recognition awards, special events, workshops, seminars, conferences, Heritage Matters (the OHT’s magazine), Doors Open Ontario, and Heritage Week (the third week of February each year), among many others (OHT, n.d.). By educating the public on conservation, it creates awareness within communities to recognize and value their local heritage.

Google Maps (Source). (n.d.). The map identifies the built heritage sites, located in Ontario, that the Ontario Heritage Trust holds [digital image]. Retrieved from http://www.heritagetrust.on.ca/en/index.php/property-types/buildings

Ontario Heritage Trust (Source). (n.d.). “The Trust’s Integrated Conservation Strategy is designed to protect the complex layering of history and the ways it is represented in our communities, to recognize and support the intersection and interplay of all forms of heritage – cultural and natural, tangible and intangible” (OHT, n.d.) [digital image]. Retrieved from http://www.heritagetrust.on.ca/en/index.php/pages/sites/conservation

Birkbeck Building:

Environmental: Through its adaptive reuse, and its approach to environmental controls, the building is a testament to environmental sustainability (Bubelis, 2009, p.5). The Birkbeck Building maintains low operation costs due in part to the following inherent environmental qualities:

- The buildings orientation on the site

- The building is open on three sides to street frontage, a side lane, and a rear courtyard which allows for plenty of opportunities for light to penetrate the structure (Bubelis, 2009, p.7)

- The indented courtyard on the west façade allows for additional late afternoon lighting

- The double-hung operable windows

- Provides natural light

- Allows for natural ventilation and cooling – before air conditioning was around

- The interior walls

- Contain frosted glass partitions to provide privacy and allow light to reach the buildings inner spaces

- Transom panels to channel air between private offices and the corridor

- The interior plan

- The varying ceiling heights on the ground, second, and upper floors allow light infiltration

- The offices are located around the perimeter walls with the stairs, washrooms, and storage vaults nears the party wall (Bubelis, 2009, p.7)

- Reducing the carbon footprint

- Close to public transit

- Walk-able amenities

- Thick exterior stone walls

- Good insulation

- High thermal inertia

Mah, S. (Photographer). (2016). The second-floor semi-circular horizontal windows that rotate on a central pivot. The operable windows allow the occupants to control the environmental conditions of the interior [photograph]. Toronto.

Mah, S. (Photographer). (2016). The transom panels that are located on interior walls, act to channel air between the offices and the corridor [photograph]. Toronto.

Economic: The OHT’s decision to adapt an existing structure as rentable office space to various tenants ensures that the building will be able to maintain sources of income. In the article titled “Sustainability for Old Buildings: A Developer’s Perspective” by Alex Speigel published in Heritage Matters (2007), Speigel states that “the marketing benefits of a conversion are significant. Older buildings provide greater floor-to-ceiling heights, unique architectural details and historical façades. Purchaser demand for historical buildings translates into positive publicity, higher sale prices and faster sales. Sales were brisk in all three of these projects – a testimony to the public’s heritage appreciation” (OHT, 2007, p. 17). Therefore, economic sustainability is attainable thanks to the demand for conservation projects, and the new life that they provide for heritage buildings.

When comparing the different pillars of sustainability, it is obvious that the environmental sustainability of the Birkbeck Building is most prominent. Thanks to the several inherent qualities listed above, the Birkbeck Building demonstrates that older existing buildings can still challenge today’s green building designs. In the Birkbeck Building, there is an interaction between environmental and social/cultural sustainability. The original design elements which give the building its environmental sustainability are conserved because of the efforts taken to ensure the social/cultural sustainability.

Ontario Heritage Trust:

Environmental: The OHT takes into consideration the conservation of natural heritage sites. By protecting Ontario’s rich and diverse landscapes, the OHT is ensuring “that our natural heritage remains a viable and significant part of our future” (OHT, n.d.). As stewards of natural heritage, “the Trust holds approximately 9,100 acres (nearly 3,700 hectares) for the people of Ontario” (OHT, n.d.).

Social: The OHT believes that promoting public awareness of conservation through various programs, encourages the public to advocate for natural and cultural heritage in their own communities. Due to the nature and structure of the OHT, they have the opportunity to work with several different organizations, businesses, individuals, and so forth. This generates relationships and partnerships between the private and public sectors. By allowing all of the different sectors to work together, the OHT in some ways creates its own little community with a common goal in mind – conservation.

Cultural: The OHT believes that heritage conservation is about “ensuring that the present and the future have the benefit of the creativity, imagination, wisdom and knowledge of our ancestors. The work of heritage conservation is not meant to freeze our communities in time, but rather to discover and protect the complex layers of our history as reflected in our communities and the multiplicity of species reflected in the natural habitat” (OHT, 2016, p. 2).

Economic: One of the aspects of the OHT’s mandate is to provide public access to many of their properties, so that everyone can experience and learn about Ontario’s rich history (OHT, n.d.). Cultural and natural heritage sites can be used to produce revenue and provide economic stability within communities at the local level throughout Ontario. This is achieved by the OHT’s support of adaptive reuse as a method of conservation, and sites used for tourism. The OHT also operates a program called ‘Heritage Venues’ in which sites and rooms can be rented out for public use/events.

MEASUREMENT

Jean Carroon’s chapter “Historically Green – What Makes Existing Buildings Green” in the book Sustainable Preservation: Greening Existing Buildings (2010) will be used to assess the environmental sustainability of the Birkbeck Building.

| List of measures (Carroon, 2010) | How the Birkbeck Building measures |

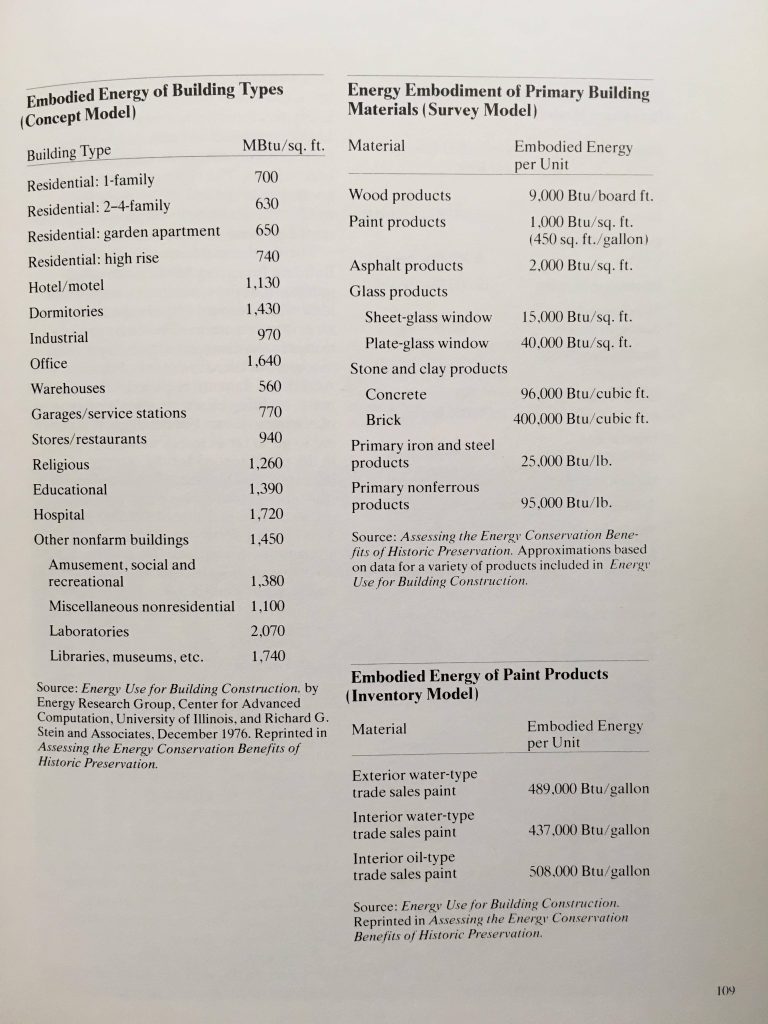

| (a) Embodied Energy – “Embodied energy is the description of energy used directly and indirectly in raw material acquisition, production of materials, and the assemblage of those materials into a building. Every building starts with an environmental debt that includes resource depletion, energy, and manufacturing from the impact of construction. Embodied energy is an attempt to quantify one significant part of this debt” (Carroon, 2010, p. 7). | The Birkbeck Building has a lower embodied energy due to its durable exterior wall construction, made of cast stone. The more durable a material, the longer it lasts. When a material is less-durable it requires frequent replacements, meaning more waste ends up in landfills, and this results in a higher embodied energy. Although cast stone may require more energy to manufacture, in the long run, the materials durability has allowed the Birkbeck Building’s façade to survive for over 100 years. |

| (b) Passive Survivability – “Passive survivability acknowledges design features in a building that allow it to function even when modem systems and energy sources fail. Vernacular and older historic buildings demonstrate passive survivability by necessity, having been constructed before dependency on off-site energy sources and mechanical systems” (Carroon, 2010, p. 10). | Two design strategies that allow the Birkbeck Building to demonstrate passive survivability are daylighting and ventilation. As discuss in the environmental sustainability section above, the excess of large windows allows for plenty of natural light to infiltrate the structure. The double-hung operable windows allow for the top sash to be lowered to expel warm air at ceiling height, while the lower sash can be raised to admit cooler air, providing natural convection (Bubelis, 2009, p.7). |

| (c) Transit-Oriented Design (TOD) and Walkability – “Recognizes the importance of providing transportation options to allow people to live and work without using personal automobiles” (Carroon, 2010, p. 11). | The location of the Birkbeck office building within the dense downtown core of Toronto, offers its occupants several transportation options, to and from work. |

Maddex, D. (Source). (1981). Embodied energy of building types [table]. Washington, D.C: Preservation Press.

“Spirit of place is defined as the tangible (buildings, sites,

landscapes, routes, objects) and the intangible elements

(memories, narratives, written documents, rituals, festivals,

traditional knowledge, values, textures, colors, odors, etc.),

that is to say the physical and the spiritual elements that give

meaning, value, emotion and mystery to place.”– UNESCO Declaration on the Protection of the Spirit of Place (2008)

REFERENCES

Books/Book chapters/Journal articles:

- Bubelis, R. (2009). Sustainable By Design: Tricks of An Old Trade. Heritage, XII (1), 4-11. Retrieved from http://www.nationaltrustcanada.ca/sites/heritagecanada.org/files/magazines/2009/issue1/F1E_1%2009-last.pdf

- Carroon, J. (2010). Sustainable Preservation: Greening Existing Buildings. Hoboken, N.J: Wiley.

- Preservation Green Lab. (2011). The Greenest Building: Quantifying the Environmental Value of Building Reuse. Retrieved from https://living-future.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/The_Greenest_Building.pdf

- Maddex, D. & National Trust for Historic Preservation in the United States. (1981). New energy from old buildings. Washington, D.C: Preservation Press.

- Tyler, N., Ligibel, T. J., & Tyler, I., R. (2009). Historic Preservation: An Introduction to Its History, Principles, and Practice (2nd ed.). New York, NY; London: W. W. Norton & Company.

Policies and reports:

- Athena Institute. (2009). A Life Cycle Assessment Study of Embodied Effects for Existing Historic Buildings. Retrieved from http://www.athenasmi.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/Athena_LCA_for_Existing_Historic_Buildings.pdf

- Government of Ontario. (1975). Ontario Heritage Act. ( R.S.O. 1990, c. O.18). Retrieved from https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/90o18#top

- Ontario Heritage Trust,. (n.d.). Memorandum Of Understanding Between the Ontario Heritage Trust and the Minister of Tourism and Culture. The Ontario Heritage Trust. Retrieved from http://www.heritagetrust.on.ca/user_assets/documents/2011-OHT-MOU-ENG.pdf

Websites:

- Parks Canada. (n.d.). Birkbeck Building National Historic Site of Canada. Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved from http://www.historicplaces.ca/en/rep-reg/place-lieu.aspx?id=7555

- Parks Canada. (n.d.). Ontario Heritage Centre. Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved from http://www.historicplaces.ca/en/rep-reg/place-lieu.aspx?id=19809&pid=0

- Taylor, D. (2014, October 26). Toronto’s Birkbeck Building at 8-10 Adelaide St. East. Historic Toronto. Retrieved October 29, 2017, from https://tayloronhistory.com/2013/12/24/torontos-architectural-gemsthe-birkbeck-building-at-8-10-adelaide-st-east/

- Ontario Heritage Trust,. (n.d.). The Ontario Heritage Trust. Retrieved from http://www.heritagetrust.on.ca/en/index.php/properties/ontario-heritage-centre/restoration

- Ontario Heritage Trust,. (n.d.). Heritage Matters archives. The Ontario Heritage Trust. Retrieved October 29, 2017, from http://www.heritagetrust.on.ca/en/index.php/pages/publications/heritage-matters-magazine/heritage-matters-archives

Banner Source: Mah, S. (Photographer). (2016). The ceiling of the Gallery [photograph]. Toronto.