Community Healing through Gardening: the Inuvik Community Greenhouse and reuse of the Grollier Hall Hockey Arena

Case Study prepared by Farah Aqrabawi, Carleton University

Keywords: Community greenhouse, adaptive reuse, Inuvik, food security, recreational gardening, socio-economic sustainability

LESSONS LEARNED

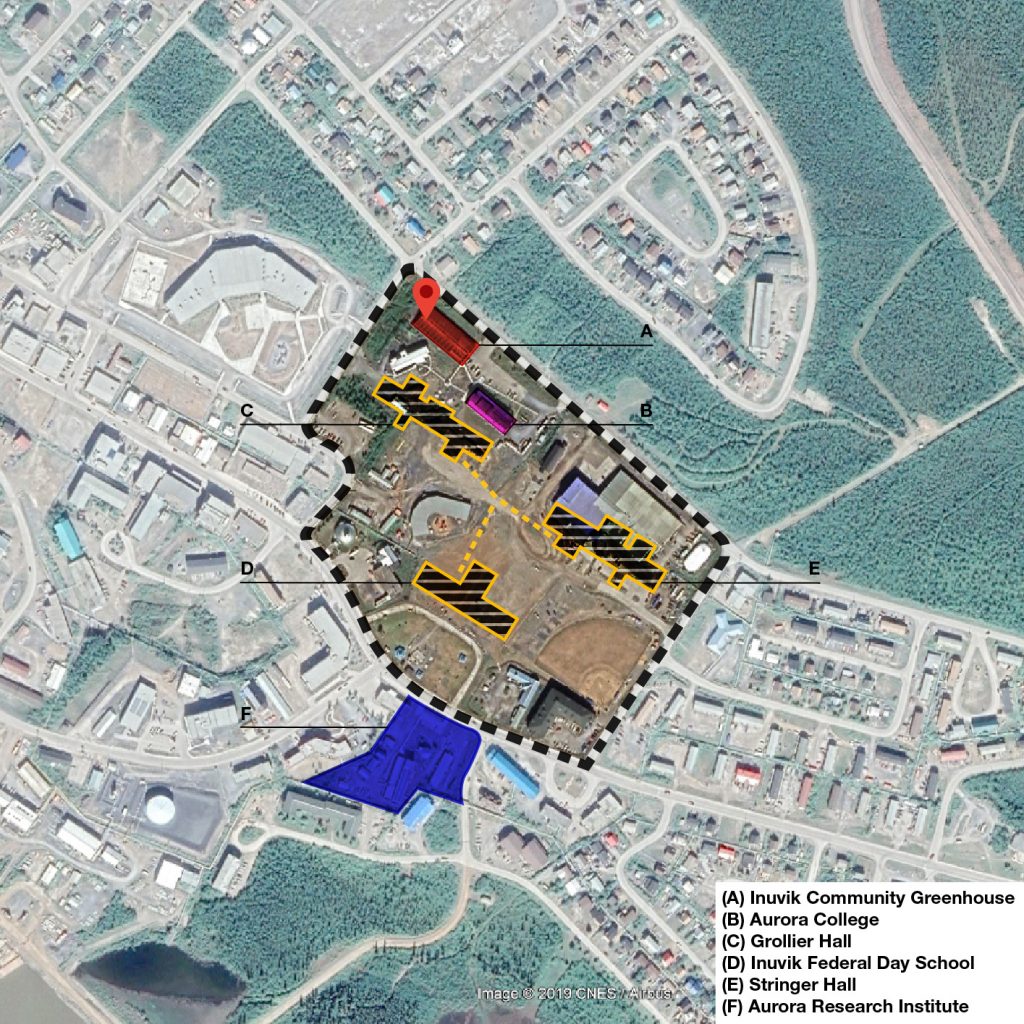

The Inuvik Community Greenhouse stands as unusual example of adaptive reuse that demonstrates how to provide an alternative way for food security through a socio-cultural and economic model. In 1998, the Community Garden Society of Inuvik (CGSI) saw the potential to convert the hockey arena, which belonged to Grollier Hall, the town’s former residential school, into a community greenhouse (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2009). CGSI raised enough funds to petition against the demolition of the hockey arena, arguing that building a greenhouse from scratch would have been more expensive (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2009). This opportunity allowed them to revive one of Inuvik’s difficult sites, part of the former Sir Alexander Mackenzie School. Committed to “building a strong sense of community through recreational gardening, food production, knowledge sharing, and volunteer support” (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2009), the efforts exerted by the CGSI led to inspiring outcomes. Based upon the success to date, CGSI believes the Inuvik Community Greenhouse serves as an effective model for other northern communities. Additionally, the building has become a destination for community members and a tourist attraction for the town of Inuvik (Carrot City Initiative, n.d.).

Through the rehabilitation of the hockey arena, the collaborative efforts among CGSI and Aurora College Access Trades Program has demonstrated that the dark symbol of the Indian Residential School in Inuvik’s history can be transformed into an emblem of hope to boost food security in the Town of Inuvik. However consistent funding from the federal and territorial government, community sponsors, and corporate sponsors is challenged by the changing nature of Inuvik’s population. Volunteer and membership turn-over is high, and relationships that have been fostered with sponsors are sometimes lost. The influence of the Inuvik Community Greenhouse has gone beyond the town’s borders as the greenhouse is supporting other communities in the North such as Fort McPherson, Tuktoyaktuk and Tsiigehtchic, providing them with advice and seedlings from plants initially grown in Inuvik. Iqaluit, the capital of the Nunavut territory, also built its own community greenhouse based on the Inuvik example.

PRESENTATION

This presentation briefly summarizing the key points and findings of the research provides a concise version of the case study’s outcomes, including images, tables, and supplementary illustrations, was given in class on November the 21st, 2019:

DESCRIPTION

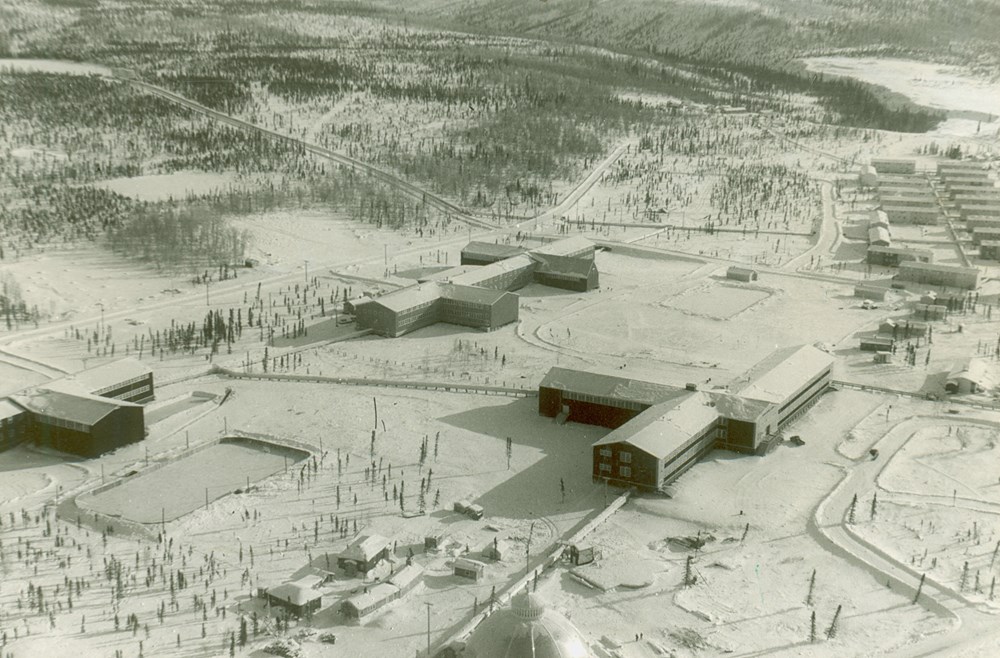

Located on the Mackenzie River Delta, two degrees above the Arctic Circle, the Inuvik Community Greenhouse is the most northern greenhouse in North America and the largest of its kind in the world with over 16,000 square feet of space in an old hockey arena (Carrot City Initiative, n.d.). Demolition of the hockey arena, which belonged to Grollier Hall, the town’s former residential school, was planned until the Community Garden Society of Inuvik (CGSI) was formed in 1998 to raise funds and petition to transform the hockey arena into a community greenhouse (Chong, P., 2012).

Objective: The objective of Community Garden Society of Inuvik was to utilize the abandoned hockey arena to allow for the production of a variety of crops in an area where fresh, economical produce is often unavailable (Chong, P., 2012). CGSI’s commitment is to “building a strong sense of community through recreational gardening, food production, knowledge sharing, and volunteer support” (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2009).

Spatial Program: The building accommodates two floors. The main floor houses the community and family garden plots made available for residents of Inuvik. There are around 74 plots, each 10 feet by 4 feet; half plots in the community that can be rented by as many as 170 members. Members commit to doing 15 volunteer hours per year and pay an annual membership fee in addition to a rental fee for a full-sized plot. Plots are provided on a first come, first served basis and gardeners choose their own plot depending on what is available. There are also plots available for elders, group homes, children’s groups, the mentally disabled, and other local charities. Other programming spaces include storage, an office for staff, a classroom for gardening classes and a gift shop for local artists to sell crafts (Chong, P., 2012). The second floor is much smaller, measuring 360 m 2, and houses a modest commercial greenhouse operation. The commercial greenhouse produces bedding plants and hydroponic vegetables. The bedding plants are grown each year and sold to greenhouse gardeners and the general public to support greenhouse revenue (Chong, P., 2012).

Right: Second Floor of Inuvik Community Greenhouse [Photo: Andrew Johnson and Virginia Sarrazin (n.d.)]

Operating Times : Located in the North Arctic, Inuvik is known as the ‘land of the midnight sun.’ It receives 56 days of 24 hours daylight in the summer and alternatively, 30 days of darkness in the winter (Chong, P., 2012). Consequently, the greenhouse only operates from May until October. Although the 24 hour summer sun heats the greenhouse, additional heat is still required at the beginning of the growing season to start planting. The summer sun also helps keep the inside of the greenhouse 10 degrees warmer than outside. Snowmelt water is also collected early in the season until the water pipes thaw (Carrot City Initiative, n.d.).

Rehabilitation: The Inuvik Community Greenhouse was originally a Quonset hockey arena that has been rehabilitated by replacing the tin roof with translucent polycarbonate glazing. Along the length of the roof, a ridge vent is set up to open automatically. To prevent cold transfer from the thawing permafrost below, the community garden plot area is built over gravel and each raised plot is insulated. CGSI reused the original structure, including floors, windows, doors, and other materials. Some of the bedding plants use recycle Styrofoam cups and milk cartons as temporary pots. A composting facility on site collects organic waster from the greenhouse and the community. Thus, the Community Garden Society of Inuvik strives to be a role model in the North for recycling and composting (Carrot City Initiative, n.d.).

TIMELINE

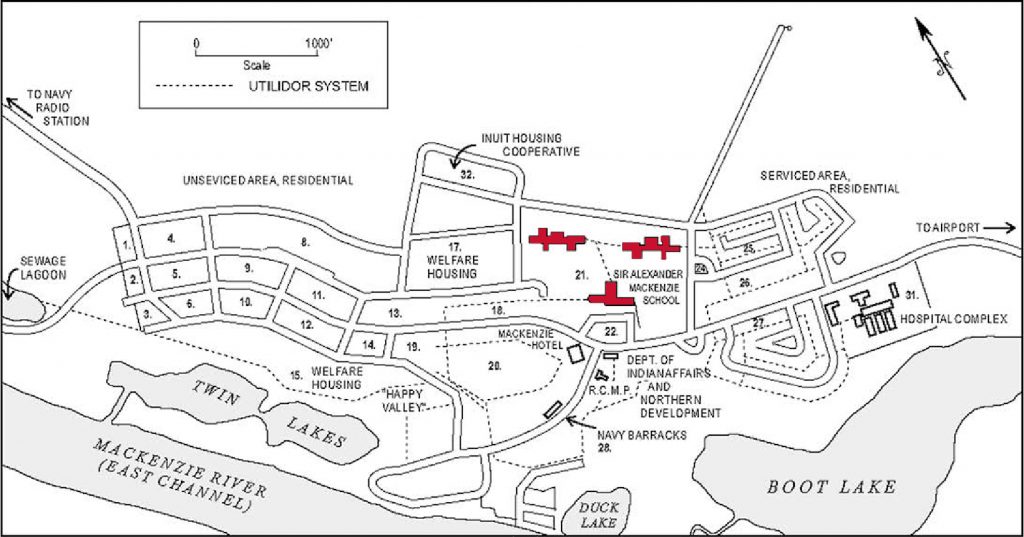

The hockey arena was part of Grollier Hall, originally part of the Sir Alexander Mackenzie School that bears the name of the first European traveler who stayed at Inuvik in July 1789 on his expedition down the river that bears his name (Detlor, n.d.). The site of Inuvik belonged traditionally to the Inuit to the North and the Dene to the south (Detlor, n.d.). The Town of Inuvik was established in the 1950s by the Canadian government as the region’s administrative center to replace Aklavik subject to flooding and erosion from the nearby Mackenzie River (Herrington, 2013). The new site search was launched in 1954 and initially referred to as East Three.

The series of events which led to the rehabilitation of the Grollier’s hockey arena follows the story of the Inuvik’s urban development history. Prime Minister John Diefenbaker’s “Northern Vision” was for Inuvik as “The first community north of the Arctic Circle built to provide northern facilities of a Canadian town. It was designed not only as a base for development and administration, but as a centre to bring education, medical care and new opportunity to the people of the western Arctic.” (Farish & Lackenbauer, 2009). In 1955, Ottawa revealed a 5-year program to open large student residential schools in major communities in Northwest Territories, adjacent to existing or planned federal day schools. Inuvik was selected as the location for the residential school halls to replace the Anglican and Catholic residential schools to be closed in Aklavik. Sir Alexander Mackenzie School opened in September of 1959; the site comprised Inuvik Federal Day School and two residential halls, Anglian Stringer Hall and Catholic Grollier Hall (Detlor, n.d.). Further details on the greenhouse site and town history are noted here:

Creation of Inuvik Community Greenhouse and related sites

- 1995 Aurora College established in Inuvik and Science Institute of the Northwest Territories merge with Aurora College to become Aurora Research Institute (Wikipedia, 2019)

- 1998 Community Garden Society of Inuvik (CGSI) initiated feasibility greenhouse study and funding campaigns (Chong, P., 2012)

- 1999 Aurora College donated Hockey Arena to CGSI and adaptive-reuse project progressed

- 2000 Inuvik Community Greenhouse opened

- 2001 Conoco Phillips, Shell, Exxon Mobil, and Imperial Oil sign a Memorandum of Understanding with the Aboriginal Pipeline Group

- 2010 Original research center facility torn down and replaced with the Western Arctic Research Center, which opened in 2011.

- 2012 SAMS School closed; construction of East Three School starts

- 2013 SAMS School demolished; opening of new East Three School

Sources: Detlor, T. (n.d.); History of Inuvik. (n.d.); CBC News. (2014); Mahoney, J. (2004); Wikipedia (2019); INTERACT (n.d.)

STAKEHOLDERS

Organizations and donors

- Community Garden Society of Inuvik – CGSI

- Government of Canada; Government of Northwest Territories – Northern Foods Development Program (NFDP);

- Aurora College Access Trades Program; Conoco Philips, Shell Canada

- Local Food banks: Inuvik Food Bank, Meadowlands Horticulture Incorporated in BC, Canada

Users and owners

- Local Inuit, Dene and other Indigenous communities in NWT

- Residents and businesses of Inuvik (gift shops, markets, composting facility)

- Community Groups (Quilters and Dyers garden, Kids Club, Inuvik Day Care, Community Group Home, Food bank sponsored by Meadowlands Inc., High School Club, Elders Garden)

- Aurora College Research Institute

Sources: (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2009), (NNSL News, 2019), (Chong, P., 2012)

The Inuvik Community Greenhouse is the result of collaborative efforts from the CGSI and Aurora College Access Trades Program and Research Institute. CGSI formed in 1998 and came together to organize fundraising campaigns and seek sponsorship from local companies. Resources to support the collaboration came from grants and donations from the Government of Canada, Government of the Northwest Territories, Indigenous groups, community sponsors, and local businesses. Sponsors in 2008 included Conoco Phillips, CIBC and Shell Canada. Non-traditional partners include local oil companies and businesses donating in-kind services (e.g., plumbers and electricians). Aurora College Trades Access Program is an important partnership in the development of the greenhouse. It has provided carpentry, plumbing, and electrical services to the Greenhouse. In 2009, Aurora College created a partnership with Western Arctic Research Institute (WARC) in which the Greenhouse provides materials and the College provides student labor and supervision (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2009).

HERITAGE

Natural heritage: The architecture of the Northwest Territories has evolved in response to the environment, and developments in construction methods, architectural forms, technology, and the changing climate (Therrien, 2015). Inuvik replaced Aklavik as the regional administrative centre for the territorial government because Aklavik suffered from decades of flooding due to its location along the Peel Channel, one of numerous waterways crisscrossing the Mackenzie River Delta. Eventually, the current site of the town of Inuvik was chosen and was located on a plateau overlooking the East Channel of the Delta, 97 km inland from the Beaufort Sea (Herrington, 2013). Located two degrees above the Arctic Circle, the Town of Inuvik faces harsh climate conditions such as extreme temperatures ranges that could range from -57 degrees Celsius in winter to 32 degrees Celsius in summer; thus, causing dramatic shifts in freezing and thawing (Herrington, 2013).

“Water was the agent of change in Inuvik’s founding in 1958.”

– Susan Herrington

Due to its location, Inuvik’s landscape has suffered predominately from both melting permafrost, a thick subsurface layer of soil normally frozen throughout the year where the earth has remained below 0 degrees Celsius, along with changes in snowdrift patterns. Melting permafrost affects every aspect of life in Inuvik – from transportation, water supply, food gathering, and hunting to building practices (Herrington, 2013). Water and sewer lines are built above ground in a series of utilidors on pilings. This changing climate context is critical to the protection of natural heritage of Inuvik, and its food security.

[Photo: Kevin & Ruth (2018)]

How the traditional country food harvested from the land is affected by climate change was not part of this case study, more related to the provision of fresh produce, but there is an important relationship. Economical produce is often not available; it is difficult to deliver fresh produce from the south on the Dempster Highway, a long road that travels through Yukon before crossing over the Mackenzie River by ice road or ferry before reaching the town of Inuvik (Christensen, J., 2016). Thus, natural heritage is strongly associated with community-based means of food production with the goal of strengthening the community through gardening and is inspiring similar initiatives in the Northwest Territories. (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2009).

[Photograph: Life in Inuvik, Northwest Territories (n.d.)]

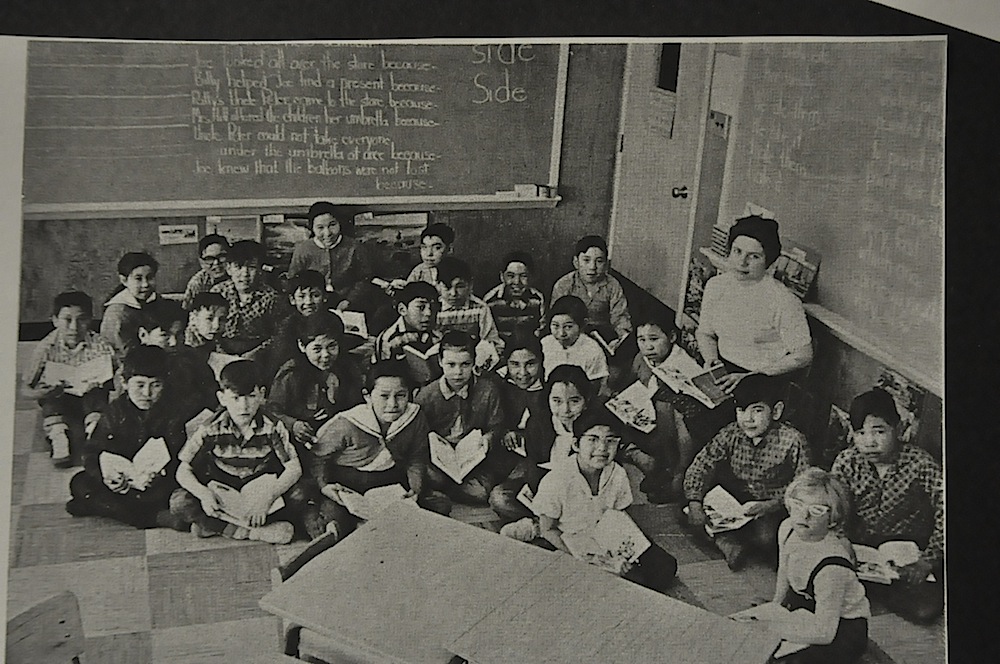

Cultural heritage: The site of the Inuvik Community Greenhouse is associated with the former Sir Alexander Mackenzie School, and the IRS system forms a backdrop to the development of the Inuvik Community Greenhouse. The introduction of a federal day school to Inuvik in the 1950s was part of the “colonial project intended for territorial occupation where the overall vision was the product of a social order foreign to the local ecology” (Therrien, 2015). Ostensibly, the Inuvik federal school (later named Sir Alexander Mackenzie School, SAMS) was intended to prepare Inuit and First Nations pupils to enter the modern world through the teaching of societal values and practical skills. However, it did so in English only, and in a physical environment that imposed its own form of imported discipline (Therrien, 2015). The forced movement of children from remote districts to assimilationist residential schools by the federal government’s control resulted in emotional and physical abuse (Farish & Lackenbauer, 2009). The church-run schools in Grollier and Stringer Halls operated until 1969, when the ownership and operation was transferred from the federal to the territorial government of Northwest Territories (General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada, 2019). The NWT government took over and supplied the staff. This was the onset for the federal schools and governments to begin to acknowledge the emotional, physical, and sexual abuse inflicted on the students.

“Not only is eating a greater diversity of fruits and vegetables good for one’s health but the act of gardening is good for the spirit.”

– Julia Christensen

Despite the site’s difficult history, the Community Garden Society of Inuvik wanted to create a positive space for the community. This connection between gardening and community is indicated by the organization’s motto, “promoting community through gardening” as mentioned by greenhouse executive director Ray Solotki (Inuvik Tourism Youtube Interview, 2015). The former Grollier Hockey Arena is also described in Julia Christensen’s chapter “from Hockey Sticks to Carrot Sticks at the Top of the World” as “Replaced by a newer facility, the arena was a weighted remnant of a difficult community past.” (2016). Currently, the greenhouse benefits the members of the community to have agency over their food security as well as to join the multiple events that take place throughout the growing season (Solotki, Inuvik Tourism Youtube Interview, 2015). Today, many community members claim that recreational gardening has been good for the spirit and well-being (Christensen, J., 2016). Thus, Inuvik Community Greenhouse becomes a part of a healing program that provides survivors of SAMS residential schools opportunities to heal themselves. This observation will be further assessed below with reference to Clarkson, L., et al. (1992). “Calls to Actions – Our Responsibility to the Seventh Generation, Indigenous Peoples and Sustainable Development”.

SUSTAINABILITY

Environmental Sustainability: Inuvik’s land, and most other Arctic communities, is compromised predominantly of thick layer of permafrost, whose top layer normally thaws during the summer months, creating an active layer above the frozen permafrost. Moreover, this active layer is crucial to the ecological hydrology of the Arctic region as the stratum where animals and insects burrow and plant roots grow (Western Arctic Handbook Committee 2002: 275).

Given this ‘top-down thawing’, the active layer has increased in depth as more permafrost melts. According to landscape architect Cornelia Hahn Oberlander who designed the landscape for East Three School across the Inuvik Community Greenhouse, “In some instances, 20 cm of viscous earth has formed over frozen soil that has resisted melting” (Pin & Oberlander: 2009 in Herrington, 2013). Consequently, the water from the melting snow and increased rain, trickles through the active layers and becomes trapped – unable to penetrate the solid permafrost below. Thus, trapped water results in the “drunken layer” where pools of standing water kill plants, that usually thrive in dryer soils, as seen in fig.11. Additionally, oversaturated soil also results in cracked foundation walls, distorted windows and doors, damaged plumbing, destabilized trees (called drunken forests) and slumped land.

By producing affordable, healthy, locally produced food through community gardening, Inuvik greenhouse encourages environmental awareness and respect for nature (Chong, 2012). Additionally, convenient compost collection from the community in Inuvik enhances the quality of the soil (Inuvikgh, 2017).

Socio-cultural Sustainability: As a not-for-profit organization, greenhouse volunteers recognize the importance of their role as active participants oriented towards the common good (Chong, 2012).

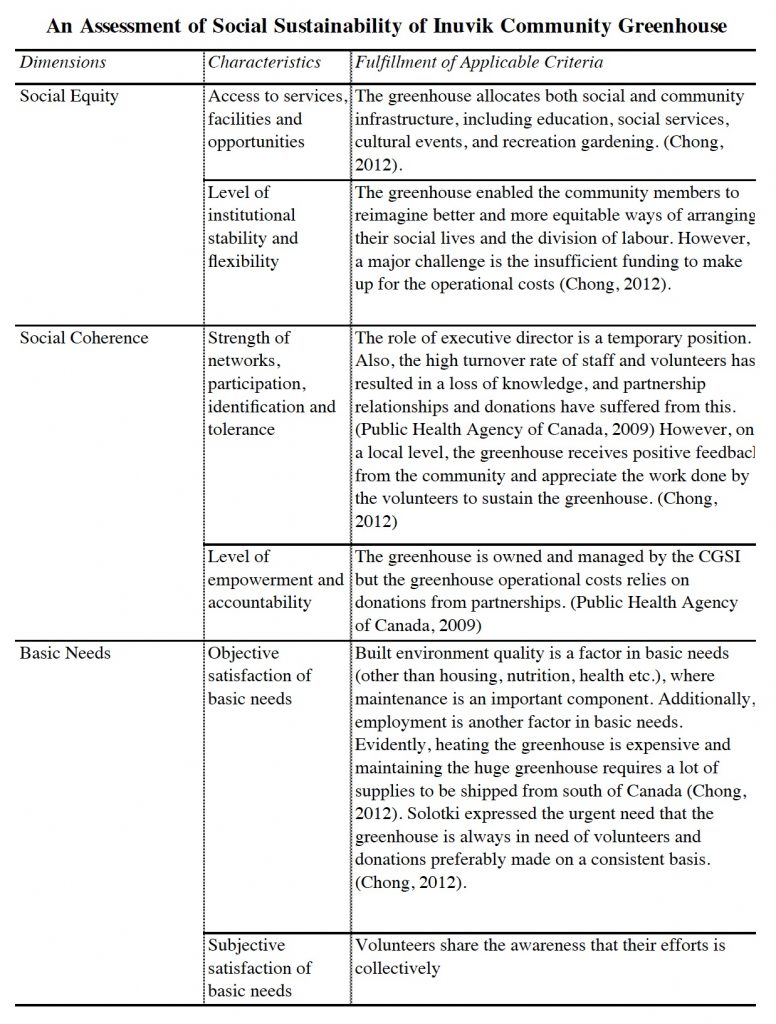

Food Sustainability: Due to the dramatic shifts in temperature and the effects of thawing permafrost on the land, the Community Garden Society of Inuvik is encouraging the greenhouse educational program to make sure everyone understands this is meant to supplement traditional ways – not change them (Solotoki, n.d.). Indigenous groups register for workshop training sessions to learn more about alternative ways for food production rather than relying on hunting and fishing. Much of this new knowledge is shared between gardeners who meet one another in the greenhouse, leading to the development of a new kind of local knowledge in the community (Christensen, J., 2016). Inuvik Community Greenhouse also signed a partnership with Aurora College Research Institute to engage in pilot project “The NWT Native Seed Development Project: Moving Towards Local Seeds for Local Remediation,” which contributes to the greater good of food security in NWT. In spite of the recognition of the ecological benefits carried by native plant seeds, there is still no commercial source of plant materials native to the NWT (Aurora College Research Institute, n.d.).. In response to this, ARI initiated the NWT Native Seed Development Project with two main objectives:

- The collection, testing, and development of technology for propagating native plant species that would be suitable for use in reclamation and revegetation in the NWT.

- The eventual commercial release of native seed varieties appropriate for the biophysical regions of the NWT and Canada’s north.

Because they are well adapted to local climatic conditions, native plant species have the potential to be successful in the reclamation of northern habitats. Thus, this allows for better long-term survival, and fewer maintenance and fertilizer requirements. In the NWT, there has been a long-recognized need for a source of native plant materials for reclamation purposes. According to Aurora College Research Institute, using native plant species for revegetation of disturbed habitats will help to maintain ecological integrity, natural successional processes, wildlife habitat, and environmental aesthetics (n.d.).

Economic Sustainability: The Inuvik community greenhouse has enabled community members to reimagine better and more equitable ways of arranging their social lives and the division of labour (Chong, P., 2012). However, a major challenge is the insufficient funding to make up for the operational costs. Additionally, there is a high turnover at the board level and among volunteers due to the large amount of work required to run the greenhouse (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2009).

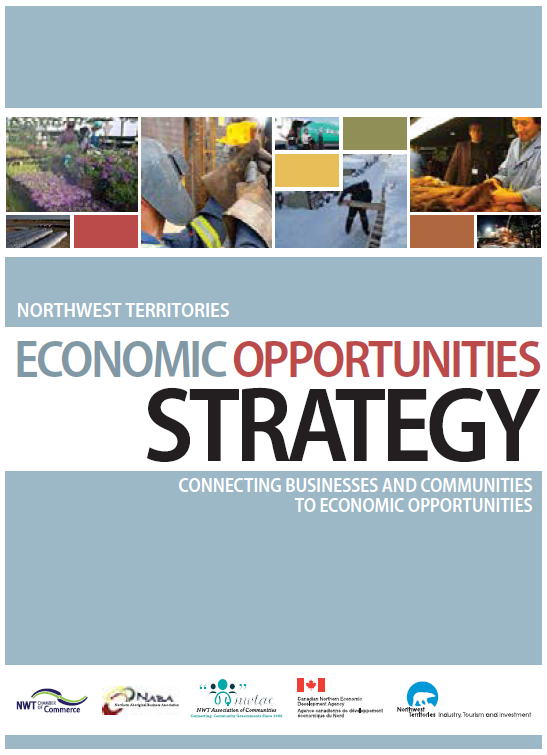

Yet, in 2000, the Economic Opportunities Advisory Panel outlined four themes that have emerged as the cornerstones of the NWT Economic Opportunities Strategy. Theme 03 “Regional Diversification” highlights the importance of expanding the potential of agriculture sector in Northwest Territories. This strategy proposes one target to promote and realize greater opportunities for the NWT economy – as stated in Target 5 that states “Build Sectors Using Regional Strengths” (NWT Economic Opportunities Strategy, 2000). The challenge of realizing these wide-ranging opportunities and converting them into real and tangible economic development is one best evident in the success of the Inuvik Community Greenhouse. According to the NWT Economic Opportunities Strategy, the Agriculture sector has grown dramatically over the past decade and now ranges from small community gardens to commercial greenhouses. While the Inuvik Community Greenhouse has contributed to the local food security, it has also boosted the local food economy (Christensen, 2016).

MEASUREMENT

The assessment of the Inuvik Community Greenhouse will consider evaluating the ideas introduced under Sustainability.

Assessing Economic Sustainability

This table identifies each of the recommended actions in the NWT Economic Opportunities Strategy and describes the expected timeframe in which activities associated with the recommended action will be initiated. In the Strategy short term was defined as 2013 – 2015; medium term is 2015 – 2019 and long term is beyond 2019.

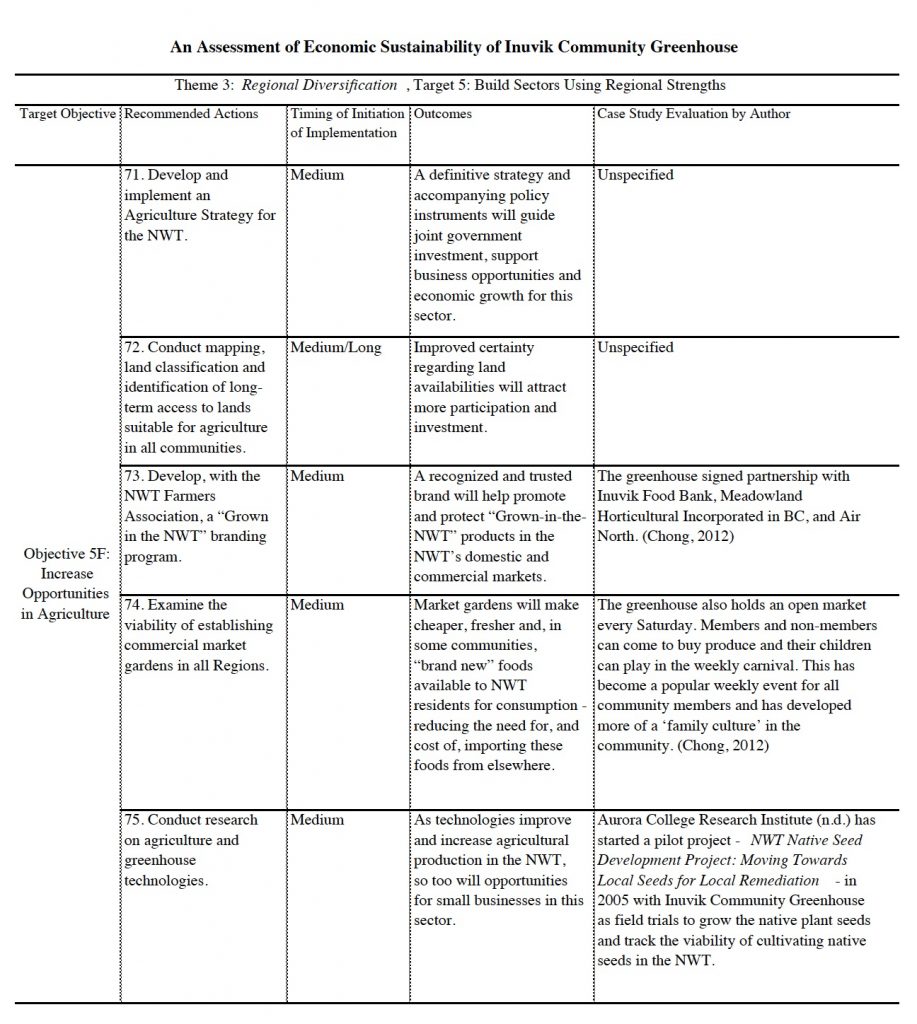

Assessing Socio-cultural Sustainability

Dr. Chris Landorf (2011) developed a comprehensive evaluation criteria for the social sustainability of historic urban environments:

Based on Clarkson, L., et al. (1992). “Calls to Actions,” Our Responsibility to the Seventh Generation, Indigenous Peoples and Sustainable Development:

| Policy | Fulfillment of Applicable Call to Action |

| “Healing programs must be developed to ensure the health and well-being of current and future generations to ensure the maintenance of sustainable societies” (Clarkson, 1992, p 84). | The communal approach of the greenhouse was designed to include members and volunteers, both men, women, youth, and elders, regardless if they were First Nations, Inuit, Metis, Aboriginal or not. This is expressed in the main motto of the greenhouse ‘promoting community through gardening’. (Chong, 2012). |

| “Healing programs must be focussed on the re-integration of mind, body and spirit.” (Clarkson, 1992, p 85). | In the past, Peter Clarkson has even referred to the greenhouse as a “community wellness centre” (Langston, n.d.). Several greenhouse gardeners expressed the positive therapeutic aspects of gardening-during the summer months, where they can escape to a quiet, tropical oasis in the heart of the community and tend plants to their hearts’ content. (Christensen, 2016) |

| “The “client” relationship in helping services must be eliminated if real healing is to occur” (Clarkson, 1992, p 85). | There is an increase in awareness and appreciation for food security across indigenous and non-indigenous members of the greenhouse, which creates a communal healing rather than one healing the other (Chong, 2012). |

| “It must be recognized that reconnecting with the land is a central part of the healing process, and initiatives must be supported that provide for this dimension” (Clarkson, 1992, p 86). | While the greenhouse is situated on the former site of the Sir Alexander Mackenzie School, healing activities depends on the greenhouse ability to provide survivors of SAMS residential schools opportunities to heal themselves (Mahoney, 2004). |

United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (2015):

Summary: Whilst assessing the results above, it is clear that the Inuvik Community Greenhouse performs quite well in terms of maintaining cultural and social sustainability through recreational gardening, food production, knowledge sharing, and volunteer support, especially within the main objective of boosting the local food security since traditional knowledge of hunting, fishing etc..cannot be easily practiced granted the harsh climates endured by Inuvik. However, there is a lack of protection of the economic sustainable model through direct policies and practices affecting the supplies and maintenance requirements for the greenhouse. Furthermore, there could be more attention on the natural environment and what it has to offer for the sustainability of site as well as its ties to the healing processes introduced by learning an alternative way of food production, such as gardening.

REFERENCES

Books/Book chapters/Journal articles

- Arnold, C. D. (1986). “A Nineteenth-Century Mackenzie Inuit Site near Inuvik, Northwest Territories.” Arctic, 39(1). doi: 10.14430/arctic2038

- Christensen, J. (2016). Care, cooperation and activism in Canadas northern social economy. Edmonton, Alberta, Canada: Polynya Press/University of Alberta Press.

- Landorf, C. (2011). “Evaluating social sustainability in historic urban environments.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 17.5, 463-477.

Policies and reports

- Public Health Agency of Canada. (2009, November 2). Northwest Territories: A Profile of Promising Practices from Canada and Abroad – Inuvik Community Greenhouse.

- Northwest Territories (NWT) Economic Opportunities Strategy. (n.d.). Retrieved November 12, 2019.

Websites

- Clarkson, L. et al. (1992),“Calls to Actions,” Our Responsibility to the Seventh Generation, Indigenous Peoples and Sustainable Development, International Institute for Sustainable Development. 77-92.

- CBC News. (2014, May 3).Inuvik’s Sir Alexander Mackenzie school demolished, CBC News. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- Chong, P. (2012). Inuvik Community Greenhouse. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- Detlor, T. (n.d.). History. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- Herrington, S. “Designing with water above the Arctic Circle: East Three School.” Journal of Landscape Architecture 8.2 (2013): 44-51.

- History of Inuvik. (n.d.). Retrieved November 10, 2019, from .

- INTERACT. (n.d.). Western Arctic Research Centre. Retrieved December 1, 2019, .

- Mahoney, J.(2004, July 12). “Hothouse flourishes as rink turns over new leaf.” City Farmer. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

- NNSL News. Around The North: Greenhouse plans year-round garden in Inuvik. Retrieved September 7, 2019.

- Pilon, J.-L. (n.d.). Inuvik. Canadian Museum of History.

- Solotoki, R. (n.d.). Community Garden Society Creation in the Beaufort Delta and Coastal Communities.

- United Nations. (2015).Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform.

- Wikipedia. Aurora Research Institute.

Feature image source: Education and Research Archive.