A sustainable heritage case study prepared by Alison Creba, Carleton University

Keywords: Apartment Towers, Toronto, Renewal, Sustainability, Modern Heritage, Partnerships

LESSONS LEARNED

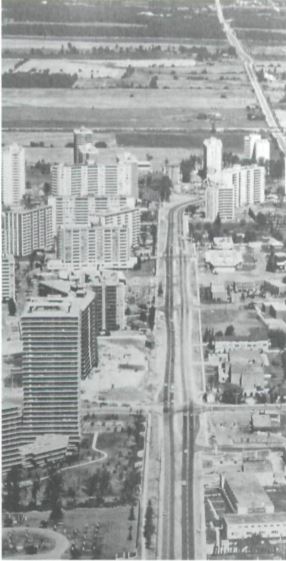

Image source: cugr.ca

As a large-scale project that reflects on the sustainability of modernist principles and design as they are applied to the high-rise apartment tower typology, the Tower Renewal project offers several lessons applicable on both global and local scales. Specifically, the project attends to the broad and local lived conditions of the towers as well as the possible outcomes when they are neglected. In this way, Tower Renewal project provides a Canadian example on the importance of both the physical condition and lived experience as indicators of future sustainability.

Significant not only as emblems of modern heritage, these towers represent an important segment of the affordable housing stock available in the Greater Golden Horseshoe (GGH) area of Toronto (ERA, 2015). Of particular relevance in the wake of the recently announced National Housing Strategy, this case reinforces a need for accessible and sustainable housing, while offering a lesson in ownership and community partnership as key to strategies for the sustainable conservation of accessible housing.

Finally, weighing both environmental and experiential indicators, Tower Renewal requires a holistic measurement of sustainability not typically provided through local guidelines. Relying on a stepped program which engages both micro and meta level stakeholders, this project offers a lesson in holistic evaluation and implementation strategies.

PRESENTATION

A presentation delivered on November 21, 2017 provided an introductory summary of the Tower Renewal initiative. Including a description, timeline and analysis of the sustainable aspects of the initiative, much of the content summarized in this presentation has been expanded up on in this case study.

DESCRIPTION

Image source: Stewart, 2008, p.23

“In Toronto, an unusually large number of high-rise apartments poke above the flat landscape many miles from downtown . . . this is a type of high density suburban development far more progressive and able to deal with the future than the endless sprawl of the US. . .” Richard Buckminster Fuller, 1968

(Stewart, 2008, 23)

Built primarily between 1945 – 1984, the suburban apartment towers found in Southern Ontario not only typify an international approach to housing characteristic of the modern era, but reflect a physical and cultural landscape unique to the region (Stewart, 2008). Recognized as the highest energy users with the lowest waste diversion rates, these towers are also closely linked to areas of social need (Ontario, 2010). Faced with decades of neglect, many now require substantial upgrades (ERA, 2015 and Monsebraaten, 2014). Home to approximately one-million residents, the nearly 1,925 apartment towers found in the GGH are indicative of the scale and complexity of this issue (ERA, planning Alliance and Cities Centre, 2010). In addition to the challenges they present, these towers are also celebrated as vibrant cultural centers and valued residences in an increasingly competitive housing market (Micallef, 2017). Both ubiquitous and unique, these post-war high-rise apartment towers offer a distinct opportunity to consider how this legacy of modernism influences shifting notions of conservation.

An ambitious initiative, Tower Renewal is referred to here as both a general concept and a specific project whose objectives are to: “transform Canada’s remarkable stock of mid-century apartment towers and their surrounding neighbourhoods into more complete communities, resilient housing stock and healthy places, fully integrated into their growing cities.” (towerrenewal.com). In addition to addressing challenges relating to the environmental, economic and social sustainability of this housing typology, Tower Renewal addresses related issues of transportation, accessibility, economic opportunity and community development. Facilitated through a partnership between public, private and voluntary organizations, the Tower Renewal Partnership addresses these issues through focused projects in the following impact areas: Green House Gas (GHG) Reduction, Growth, Complete Communities, Affordability, Housing Quality and Culture (towerrenewal.com).

As distinct communities operating in high-density arrangements, these apartment towers already embody a strong existing framework on which to improve. With innumerable facets, Tower Renewal is of particular interest as a sustainable heritage case study for its emphasis on the notion of ‘standard of care,’ which enforces the importance of qualitative treatments as well as the technical details in achieving large-scale results. Drawing on a broader discussion of methods for qualitative assessment within heritage conservation (Stubbs, 2004 and Rodwell, 2003), this case study considers the notions of ownership and agency as key attributes of a sustainable heritage approach to Tower Renewal.

A BRIEF HISTORY:

Image source: Lockwood Survey Corporation Ltd in Stewart, 2008

The story of high-rise apartment towers in the GGH area emerges in relation to the 1954 formation of Toronto’s Metropolitan government.

Expanding its borders to include Toronto as well as adjacent townships and villages, the creation of the Metropolitan city was intended to encourage growth through the unification of infrastructural services and explicit planning initiatives (Stewart, 2008, 24). A key function of this plan was to promote a controlled ‘expansion’ of the city through the introduction of satellite models (Stewart, 25). Emblematic of a cultural confidence that emerged in the wake of the second world war, high-rise apartment towers also represented a highly lucrative real estate venture fuelled by a strong economy (Stewart, 27). When combined, these factors spurred the development of the high-rise apartment tower typology in Metropolitan Toronto.

However, as with many projects of the modern era, these towers also represent unsuccessful attempts to address broad social, economic and environmental issues through design. In conjunction with critiques of modernist planning and design, perceptions of the suburban apartment tower typology declined in the decades following their emergence (ERA, 2015). Despite, or perhaps because of the decades of physical and cultural neglect, in the early-2000s, not only the towers themselves but the communities who lived there began to garner recognition for their unique contribution to the regional landscape (Stewart, 2008 and NFB, 2009).

In 2009, the city formed an official Tower Renewal Office where ongoing research and implementation strategies are developed. Since this time, much headway has been generated through the launch of a pilot series, and subsequent reviews. At the time of this publication, the Tower Renewal initiative remains an active and expanding project with many dynamic facets.

TIMELINE:

1942 Toronto Planning Department established, soon followed by the Toronto and Suburban Planning Board 1954 Metropolitan Toronto established 1945 – 1984 Towers Built 1966 Peak of Toronto’s first mass housing boom 2008 Conversation around Tower renewal begins to make its way to the municipal level – City Council recognizes Tower Renewal as an opportunity to make progress on a range of City initiatives 2009 ERA Architects, planningAlliance and Cities Centre at the University of Toronto, are commissioned by the Ontario Growth Secretariat, in the Ministry of Infrastructure, to analyze this housing resource and examine its future role in our growing region. 2009 Tower and Neighbourhood Revitalization Unit is established at Toronto City Hall 2009-2011 Pilot sites established 2010-2011 Development of City-Wide Rollout Strategy 2011-2030 Implementation of City-Wide Rollout Strategy 2017 (August) Residential Apartment Commercial (RAC) Zoning launched 2017 (November) Federal Government introduces National Housing Strategy STAKEHOLDERS:

Image source: [above] City of Toronto, 2013, 23 [below] Tower Renewal Partnership, 2016, 2

As a broad initiative which affects micro and macro level issues, the Tower Renewal initiative has numerous stakeholders. While this is summarized through a list of associated individuals and organizations in the table below, two key themes characterize the project: ownership and partnership.

OWNERSHIP characterizes the challenges and opportunities distinct to Tower Renewal. Despite the homogenous appearance of the tower-typology, diversity of ownership (80% are privately owned) contributes to unique issues which are dependent on regional market conditions and infrastructural support (“Tower Renewal Financial Instrument”, 2016). As well, although several towers may be clustered together in groups, since their construction, these clusters have been fragmented amongst different owners posing a challenge for future infill development (“Understanding”, p. 7). Further, representing a significant portion of the rental market, the apartments contained therein constitute a significant stock of the region’s affordable housing options (Micallef, 2017). Understood broadly, ownership affects both individual and collective agency to enact change. As the below list of stakeholders demonstrates, the complexity of this relationship necessarily implicates a dynamic representation of public and private stakeholders.

PARTNERSHIP is also a central theme to the Tower Renewal initiative. As an issue relevant to multiple municipalities, disciplines and individuals, the project is facilitated through the Tower Renewal Partnership – a formal collective of public, private and voluntary sectors who engage in research, advocacy and implementation (cugr.ca). Tower Renewal Partnership reflects a methodological approach based on establishing strong collaborative links that address multi-scale relations – ranging from resident initiatives to zoning policy. Representing both private and public consultants in the field of energy retrofits, planning policy, green financing and social entrepreneurship, of note are the vast contributions from academic and cultural institutions who in addition to researching this theme, are also involved in interpreting and disseminating the experiences of tower communities (cugr.ca/). While this academic attention can be understood to progress the representation of the initiative, a critical analysis may question the effect of this attention on the communities who live in tower structures. In the past, analogous studies on specific housing complexes have resulted in a community malaise related to ongoing research. Here, it is important to consider the approaches and impact of academic or other research related to a particular community.

| Users | Residents, patrons of local businesses / services |

| Private Sector | Building owners, Centre for Urban Growth and Renewal, DKGI, ERA Architects, Evergreen, Foodshare, Halsall Engineering, Independent Electricity System Operator, Maytree, N. Barry Lyon Consultants, planningAlliance, Resident-owned businesses, (Sustainability Consultants), Transsolar KlimaEngineering, United Way Toronto and York Region |

| Public Sector | City of Toronto divisions, agencies, boards including:

Affordable Housing Office • Children’s Services • City Planning • Finance • Economic Development & Culture • Emergency Medical Services • Employment and Social Services • Fire Services • Municipal Licensing & Standards • Office of Emergency Management • Office of Partnerships • Parks, Forestry & Recreation • Public Health • Shelter, Support & Housing Administration • Social Development, Finance & Administration • Solid Waste Management • Toronto Building • Energy and Environment Office • Toronto Water • Transportation Services • Toronto Public Health • Toronto Community Housing Corporation • Toronto Police Service (Accomplishments, p 18) As well as the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation, Federal Government of Canada, City of Hamilton, City of Mississauga, City of Ottawa, Growth Secretariat – Government of Ontario, Ontario Building Envelope Council, Toronto Community Housing, Toronto Hydro, Toronto and Region Conservation Authority |

| Voluntary Sector | archiTEXT Inc., Arup, Atkinson Foundation, The Canadian Urban Institute, Carleton University, Cement Association of Canada, Clinton Foundation, City Studies – University of Toronto, The City Institute (CITY) – York University, Daniels School of Architecture, East Scarborough Storefront, Greater Toronto Apartment Association, HIGHRISE: National Film Board, Institute Without Boundaries: George Brown College, J.W. McConnell Family Foundation, Jane’s Walk, Metcalf Foundation, OCAD University, Ryerson University, Scarborough Campus, Seneca College, Sustainable TO, The Toronto Society of Architects, Toronto Atmospheric Fund, Tower Wise, Zero Footprint. |

(sources: towerrenewal.ca/, cugr.ca/, www1.toronto.ca/)

Note: A wide range of international institutions involved in related work serve as a reference for innovative technical and economic renewal models(“Tower Renewal Financial Instrument”, 2016 and “German Retrofit Financing”, 2016). Although theses institutions as well as designers and fabricators and engineers represent related networks implicated in advancing renewal strategies, they have been excluded from this list as stakeholders directly involved in this project.

HERITAGE:

While not recognized by any official heritage designation, over the last decade post-war high-rise apartment towers have received attention for their distinct cultural and natural legacy in a range of heritage-focused publications. Although the following section initially presents the towers through a split cultural / natural heritage lens, it ultimately suggests that as participants in Tower Renewal, these towers take part in a recent yet historic transformation defined by an integrated approach to conservation. As both a process and product, we may consider Tower Renewal as an example of living heritage.

Flemingdon Master Plan. Image source: Stewart, 2008

CULTURAL HERITAGE: Recognized as distinct products of modern planning and architectural ideals, these post-war apartment towers are simultaneously ubiquitous and unique to the landscape of southern Ontario. Built within the specific historical and economic conditions, these towers offer a unique contribution to a larger story of mass-housing found the world over (towerrenewal.com/). Vast in number, these towers are considered defining features of the region’s civic and social identity (Stewart, 2008). Conceived in this way, these towers can be considered within the realm of a broadening definition of heritage which, in contrast with the conventional celebration of singular and iconic structures, recognizes the physical and cultural legacy of entire building stock (McClelland, Cohen and Paglialunga, 2017).

Image source Stewart, 2007 (also in Ross, 2008)

NATURAL HERITAGE: Considering the “Tower in the Park” model, we may understand these towers in relation to their surrounding open space and natural features. Built in conversation with Toronto’s substantial ravine system, the sub-urban tower typology in the GGH is characterized by its distinct relationship to the regions’ natural attributes. Indeed, in a recent Ravines and Wedges Workshop on Metropolitan Landscapes, reinstating the relationship of towers to Toronto’s ravine systems was identified as a crucial step toward neighbourhood resilience and ecological health for the 21st century (towerrenewal.com).

Image source: cugr.ca/

“Buildings go through cycles, or at least our relationship with them does”

(Stewart, 2007)

LIVING HERITAGE: Often referred to as intangible cultural heritage, in 2003 UNESCO enacted a convention which defined the term as: “This intangible cultural heritage, transmitted from generation to generation, is constantly recreated by communities and groups in response to their environment, their interaction with nature and their history, and provides them with a sense of identity and continuity, thus promoting respect for cultural diversity and human creativity” (UNESCO, 2003). Given the ongoing provision of accessible housing, the reinterpretation of original environmental design intent and the role of international examples in the evolution of the typology, we may consider these towers and the generations of residents as examples of living heritage. These attributes are explained in more detail below:

- Primarily comprised of rental units, these towers participate in a key characteristic of the modernist era which sought to serve the public interest, through the provision of accessible housing (Ross, 2008). The retention of this aspect of the towers is not only a key aspect to their renewal, but may thus considered a part of their ongoing heritage.

- Re-thinking the use of the open space is another example of these towers as living heritage. Incorporating existing community needs and practices into an adaptive reuse of the surrounding “natural” and open landscape. In addition to revising zoning by-laws, community gardens and markets have been proposed as a way of accessing and interpreting the neighbouring land (Stewart, 2007).

- Despite original environmental objectives of conservation of green space, the inefficient design of these towers has now prompted a new phase in the life-cycle of the typology. Taking cues from similar initiatives in Germany, the Netherlands and the UK, the evolution of these structures continues to participate in an international approach to architecture through adaptive design (Stewart, 2007).

To this end, as a participant in the Tower Renewal initiative, the cultural legacy of these towers may be conceived of as an ongoing practice, which manifests not only in the specific renewal initiatives but also through the generations of residents who have lived in them.

SUSTAINABILITY:

“Many ideas of current sustainable design have their roots in old ideas that were reinvented in the modern era” (Ross, 2008, 28)

An initial survey of the Tower Renewal initiative from a sustainability lens reveals an inherently ‘green’ premise – one which recognizes the inherent value of our existing building stock. However, although Tower Renewal addresses both the environmental performance of the towers themselves as well as the larger social and economic conditions of the surrounding areas, the question of sustainability must be understood in relation to its modernist legacy. As with many of the structures of this era, these mid-century apartment towers are constructed using materials and assemblies considered innovative at the time, they have since been regarded as outdated and inefficient. Further, their suburban location necessitates an unsustainable dependency on cars and mass transportation. Nevertheless, as Ross (2008) suggests, “many ideas of current sustainable design have their roots in old ideas that were reinvented in the modern era.” (Ross, 2008, 68). Indeed, despite their physical inadequacies, these structures do offer lessons about past land-use and growth-strategies as well as opportunities for the retention of affordable housing, all of which inform current sustainable efforts towards tower renewal. In addition to the lessons we may glean from the typology itself, the Tower Renewal initiative has also created the Sustainable Towers Engaging People (STEP) program which provides building owners with specific benchmarks and guidelines with which to pursue and measure environmental, economic and social sustainability.

Image source: Stewart, 2007

LAND USE – GROWTH, INTENSIFICATION AND DIVERSITY: Championed as a responsible use of land, the “Tower in the Park” model includes significant portions of surrounding open and/or greenspace[1] (Stewart, 2008, 26). While in some cases, the result is a close proximity to mature vegetation, in other cases these spaces are not necessarily accessible nor green – as structures are often surrounded by parking lots and fences (ERA, 2015). Nevertheless, part of the renewal program on these sites includes an adaptive reuse of the surrounding open space for community uses, local economic development and municipal infrastructure, such as active transportation networks (“Understanding the Tower Landscape”, 6). The recent creation of new zoning policy called the Residential Apartment Commercial zone (aka RAC zone), eases the formerly restrictive land-use around selected tower-sites (“Understanding”, 7). In expanding the possible uses for surrounding areas, this policy acknowledges the combined social and economic opportunities bound up in planning by-laws. In attending to these land-use issues, the Tower Renewal initiative aims to create more complete communities by recognizing that community sustainability is the product of integrated economic, environmental and social conditions.

Similarly, the suburban structure of existing tower neighbourhoods presents both opportunities and challenges. In this context, essential resources are stratified and thus challenging to access for residents who may or may not have access to private transportation. While provincial documents such as the Green Belt Act (2005) and Growth Plan Act (2006) both identify areas for ‘intensification’ within the urban core, when paired with the ‘Big Move’ Regional Transportation Plan, specific tower neighbourhoods may be identified as more advantageous for accommodating growth (“Understanding”, 7). Using these documents, Tower Renewal may be positioned within broader regional growth strategies that consider transportation and density.

Finally, the retention of affordable housing plays a key role in sustaining the social and economic condition of the region. (Ross, 2008, 70). A reflection of modernist ideals, economically attainable housing remains an asset which supports the broader activities of the region. As such, these post-war apartment towers may serve not only as a reference against which we measure future developments, but may also inform broader policy such as the National Housing Strategy (2017).

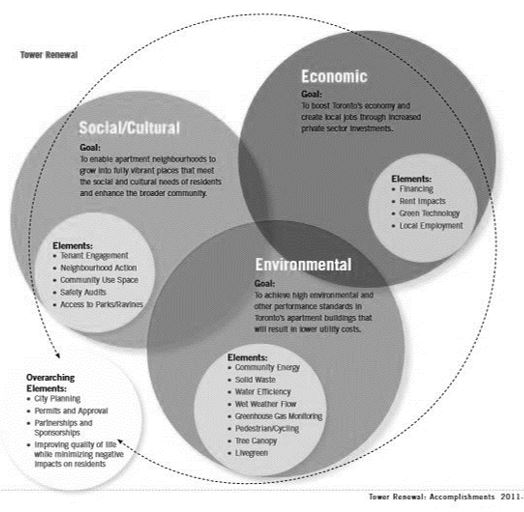

Image source: City of Toronto, 2013

SUSTAINABLE TOWERS, ENGAGING PEOPLE: The premise for the Sustainable Towers, Engaging People (STEP) program emerges from a holistic understanding that sustainability is not only determined by the physical efficiency of the building, but also by the community’s sense of agency. It follows that through engagement, property owners, city staff and other stakeholders may directly participate in ensuring that key elements of the towers perform to sustainable standards (City of Toronto, 2011, 22). Providing a Tower Renewal Toolkit, the STEP program aims to strengthen and support the capacities building owners and property managers in achieving goals outlined below by providing benchmarks and monitoring frameworks in six key areas (Energy, Water, Waste, Safety, Operations and Community). The goals for the program are:

Environmental: To achieve high environmental and other performance standards in Toronto’s apartment buildings that will result in lower utility costs. This would be measured my noting the following elements:

- Community Energy

- Solid Waste

- Water Efficiency

- Wet Weather Flow

- Greenhouse Gas Monitoring

- Pedestrian/Cycling

- Tree Canopy

- Livegreen

Social/ Cultural: To enable apartment neighbourhoods to grow into fully vibrant places that meet the social and cultural needs of residents and enhance the broader community. This component considers:

- Tenant Engagement

- Neighbourhood Action

- Community Use Space

- Safety Audits

- Access to Parks/Ravines

Economic: To boost Toronto’s economy and create local jobs through increased private sector investments. Elements:

- Financing: It will use a financing tool, called a Local Improvement Charge (LIC), to provide funding for energy and water efficiency retrofits.

- Rent Impacts

- Green Technology

- Local Employment

(City of Toronto, 2013, 5).

Supplementing the social and environmental aspects of tower renewal, the High-Rise Retrofit Improvement (HI-RIS) Program provides financial support for building owners looking to undertake improvements which fulfill the above mandates. Reinforcing the themes of partnership introduced above, the HI-RIS program directly addresses the question of the viability of Tower Renewal – that is the combined economic and environmental conditions which ensure its ongoing relevance. Ultimately, through engaging and supporting building owners and manages, the STEP program participates in a form of succession planning – an approach to long-term sustainability which aims to address local issues through grass-roots governance models (Pitter, 2016).

MEASUREMENT:

Although the Tower Renewal’s STEP program includes its own metrics for evaluating progress towards specific sustainability goals, this section sets out to assess the initiative itself. The following review considers two methodological approaches to the holistic appraisal and conservation of sustainable heritage sites. Specifically, the methods employed here focus on community inclusion and agency as an integral aspect in sustainability. In both cases, heritage is understood within a broader landscape approach.

Illustration by Daniel Rotsztain, Source: raczone.ca

PRIDE, PLACE AND COMMUNITY EXPRESSION: In his article “Heritage Sustainability: Developing a Methodology for the Sustainable Appraisal of the Historic Environment”, Michael Stubbs aims to establish a broad framework for appraising sustainability in the heritage sector (Stubbs, 2004, 285). Using case studies, Stubbs explores a range of possible settings in which sustainable heritage is to be evaluated, emphasizing the need for clearly defined heritage attributes as well as a long timeframe over which to evaluate a site (Stubbs, 288). Of particular relevance to Tower Renewal is a rehabilitation project in England’s Yorkshire and North-East region which had been identified by the National Trust to address social exclusion. In this case, Stubbs notes that over the course of the project, it became apparent that the local community remained disengaged and what was needed was a “focus on the people and not the properties” (Stubbs, 299). This project emphasizes the importance of addressing community needs in sustainable heritage initiatives. While social sustainably is admittedly one of the more complex mechanisms to measure, Stubbs offers several criteria for its appraisal (Stubbs, 302). The chart below applies these criteria to the Tower Renewal initiative, to discover the ways in which these criteria are used to imagine its sustainable future.

| Social inclusion and Community

|

One example is the inclusion of “Community” as one of 6 components in the STEP Program’s Tower Renewal Toolkit. While suggestions provided under the “Community” category include providing a welcome package to new tenants, recreation space and common areas where residents can connect with local services and events, there are no recommendations for establishing mechanisms for feedback or expressions of connection to place (Toronto.ca).

Referencing Stubbs’ advocacy for personal and collective self-esteem, we may consider the role resident’s sense of agency and ownership over their living space. One critique of the Tower Renewal’s STEP program is the absence of participation in both the monitoring of environmental resource conservation. A suggestion to remedy this includes incorporating residents in dedicated conservation committees/initiatives. |

| Civic pride and sense of place

Virtual heritage and arts and culture |

More broadly however, Tower Renewal’s initiative to create a new Residential Apartment Commercial zone, opens up the possibilities for the kinds of activities and expressions of place that can take place. Aimed to foster spaces for food, support, business, health, jobs, learning, meeting, arts and culture and active living, the RAC zone seeks to foster Stubb’s attributes through the creation of “more complete, convenient and healthy communities” (raczone.ca). |

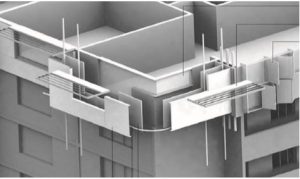

Over-cladding concept. Source: Stewart, 2007

PARTNERSHIP, MATERIALS AND HOLISTIC DEVELOPMENT STRATEGIES: The second reference emerges from Dennis Rodwell’s article (2003), “Sustainability and the Holistic Approach to the Conservation of Historic Cities”. In it, Rodwell suggests that sustainable heritage relies on both a broad definition of resource value as well as the engagement with a range of partners (Rodwell, 2003, 70). Unpacking these concepts, Rodwell advocates that an attention to materials may result in a nuanced approach to sustainability and heritage (Rodwell, 63). Introducing the concept of harmonious co-existence to understand resource value, Rodwell suggests that development may be compatible with conservation if it occurs creatively in the revitalization process (Rodwell, 65). Offering an appendix of “Co-ordinated Guiding Principles”, the below chart reviews the Tower Renewal initiative in relation to Rodwell’s approach to sustainable conservation (Rodwell, 70-71).

| Engagement with a range of partners

|

As suggested in the Stakeholders section, partnership is a key component to this project. Central to the Tower Renewal strategy, public, private and voluntary organizations all collaborate on the project. This diversity is reflected in both the broad and specific approaches to cultural, environmental and economic conservation and sustainability. |

| Attention to Materials / Creative approaches to development and conservation

|

An attention to materials is also a dominant theme within the Tower Renewal initiative. Not only are innovative approaches being taken to designing over-cladding interventions to improve the energy efficiency of the structure, but several creative formats are being tested in the effort to find a solution which is compatible with environmental objectives as well as the modern heritage of the site.

An attention to materials can also be seen in relation to housing quality – where the spatial experience of apartment units is understood as a combined product of durable materials and environmental conditions such as light, air and space. The viability of housing quality is dependent the incorporation of new materials that meet contemporary standards while retaining the economic and cultural heritage of the structure which ensures their affordability. Finally, expressions of these ideas are also present not only in a consideration of waste management systems and the retrofit of mechanical systems, but also in the methods of converting them. |

REFERENCES

Books/Book chapters/Journal articles

- McClelland M, Cohen, A.H. & Paglialunga, C. (2017) “Towers: a comparison in evaluation, context, and conservation”, Journal of Architectural Conservation, 23:1-2, 106-115, DOI: 10.1080/13556207.2017.1312762

- McClelland, M., Stewart, G., & Ord, A. (2011). Reassessing the recent past: Tower neighborhood renewal in Toronto. APT Bulletin, 42(2/3), 9-14.

- Rodwell, D., 2003, “Sustainability and the Holistic Approach to the Conservation of Historic Cities,” Journal of Architectural Conservation

- Ross, S., 2008, “How Green Was Canadian Modernism, How Sustainable will it be?” Docomomo Journal: Canada Modern (38): 67-72.

- Stewart, G. (2007). “The suburban slab: Retrofitting our concrete legacy for a sustainable future” gTOpia. Pp. 132-143

- Stewart, G. (2008). “The Suburban Tower: and Toronto’s Legacy of Modern Housing”. Docomomo Journal, (39), 23-29.

- Stubbs, M. (2004). “Heritage-Sustainability: Developing a Methodology for the Sustainable Appraisal of the Historic Environment.” Planning, Practice and Research 19:3, pp. 285-305

Policies and reports

- City of Toronto (2013) Tower Renewal Accomplishments, 2011-2013. Toronto: City of Toronto.

- City of Toronto. (2011). Tower Renewal Implementation Book. Toronto,

- Ontario: City of Toronto. Retrieved from: https://www1.toronto.ca/

- City of Toronto and Tower Renewal Office. (2012). Infill on apartment sites in Toronto: A ten-year review: Technical analysis. Toronto, Ontario: City of Toronto.

- ERA Architects, planningAlliance and Cities Centre at University of Toronto. (2010) Tower Neighbourhood Renewal in the Greater Golden Horseshoe: An Analysis of High-Rise Apartment Tower Neighbourhoods Developed in the Post-War Boom (1945-1984). Retrieved from: cugr.ca

- ERA Architects. (2015) TRP Fact Sheet. Retrieved from: towerrenewal.com

- Kesik, T and Saleff, I. (2009) Tower Renewal Guidelines: For the Comprehensive Retrofit of Multi-Unit Residential Buildings in Cold Climates. Toronto: Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Design – University of Toronto.

- Ontario Ministry of Infrastructure, E.R.A. Architects, Planning Alliance Inc, University of Toronto, & Canadian Electronic Library (Firm). (2010). Tower neighbourhood renewal in the greater golden horseshoe: An analysis of high-rise apartment tower neighbourhoods developed in the post-war boom (1945-1984). Toronto, Ontario: Ministry of Infrastructure.

- Tower Renewal Partnership. (2016). “Understanding the Tower Landscape”. Research Report. Retrieved from: towerrenewal.com/

- Tower Renewal Partnership. (2016). “German Retrofit Financing”. Research Report. Retrieved from: towerrenewal.com/

- Tower Renewal Partnership. (2016). “Green Finance and Tower Renewal”. Research Report. Retrieved from: towerrenewal.com/

- UNESCO (2003) “Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage” General Conference of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Paris, France. Retrieved from: unesco.org

Websites

- City of Toronto. (n.d) “Creating a vibrant, healthy apartment community”. Tower Renewal Program. Retrieved from: www1.toronto.ca/

- City of Toronto, (n.d) “How STEP Works”. Tower Renewal Program. Retrieved from www1.toronto.ca/

- “Tower Renewal Case Studies – Tower & Neighbourhood Revitalization Unity” (2017) City of Toronto. Retrieved from: https://www1.toronto.ca/

- Tower Renewal Partnership. (2017) Retrieved from: http://towerrenewal.com/

- Tower Renewal Partnership. (2017). “Housing Quality Standards” Retrieved from towerrenewal.com.

- Tower Renewal Partnership. (2017, May 30) “Ravines x Wedges”. Tower Renewal Blog. Retrieved from: towerrenewal.com/

News Articles

- Adelman, M. (2016) “Adding small businesses to Toronto’s high-rise residential towers” CBC News. Retrieved from: www.cbc.ca/

- BBC (2017, July 19). “London fire: What happened at Grenfell Tower?” BBC News. Retrieved from: bbc.com/

- Bozikovic, A. (2013). “Toronto hopes to revitalize its many postwar high-rises” The Globe and Mail. Retrieved from: https://beta.theglobeandmail.com/

- Lightstone, A. (2010) “The Future of Tower Renewal”. Spacing Toronto. Retrieved from: spacing.ca/

- Micallef, S. (2017) “Grenfel Tower fire a warning for Toronto on Housing Crisis: Micallef” The Star. Retrieved from: www.thestar.com/

- Monsebraaten, L. (2014, March 12) “Highrise hell for low-income families in Toronto” The Star. Retrieved from www.thestar.com/

- Pitter, Jay. (2016, August 24). “Transformative conversations about social housing”. Maytree. Retrieved from maytree.com/

Multimedia Projects

- National Film Board. (2009) Highrise: The Towers in the World, the World in the Towers. Retrieved from: highrise.nfb.ca/

Footnote:

[1] Of the sample sites, 28% were identified as having large areas of adaptable open space which may accommodate mixed-use infill (“Understanding the Tower Landscape”, p. 6).