Case Study prepared by Sampoorna Bhattacharya, Carleton University

The Sustainability of Modernist Heritage at Vincent Massey Park, Ottawa

Keywords: modernist, rehabilitation, Hart Massey, Vincent Massey Park, biophilic design

LESSONS LEARNED: Vincent Massey Park commemorates the past but also provides hope for the future, through its sustainability education as well as through its conservation of Ottawa’s collective memory. The unique modernist structures of Vincent Massey Park are connected to their natural environment. Through their vibrant colours and minimalistic style, they connect visitors of the park to nature as well. These newly rehabilitated pavilions commemorate the legacies of Hart Massey, one of Ottawa’s most innovative architects, and his father, Governor General Vincent Massey. Vincent Massey Park is located on traditional, unceded Algonquin territory. The Summer Solstice festival held at Vincent Massey Park participates in reconciling the site’s history as a park with traditional Indigenous connections to the land.

PRESENTATION: This information was presented to the class on November 21, 2017. It represents a summarized, 10 minute version of the research done for the case study.

Vincent Massey Park Presentation

DESCRIPTION: Most of the historic information on Vincent Massey Park is found in the 1993 study by Edwinna Von Bayer. Copies of this report are located at Carleton University’s Ottawa Resource Collection as well as the ‘Ottawa Room’ in the main branch of Ottawa Public Library. Information gathered in the table below was accessed through this report.

Vincent Massey Park, located southwest of downtown Ottawa and directly adjacent to the Rideau River, and across from Carleton University, is named after the first Canadian-born Governor General of Canada, The Right Honourable Vincent Massey. His son, Hart Massey, designed the award-winning pavilions for the opening of the park in 1958. These include a bus shelter, a concession building, washrooms and an entrance pavilion. Ten years after the park was opened, a new pavilion, the “centennial bandstand” was introduced to the park.

Clockwise from top left to bottom left: Bus Shelter, Concession stand, new washroom building, centennial bandstand. Photographs by Sampoorna Bhattacharya, taken November 2017.

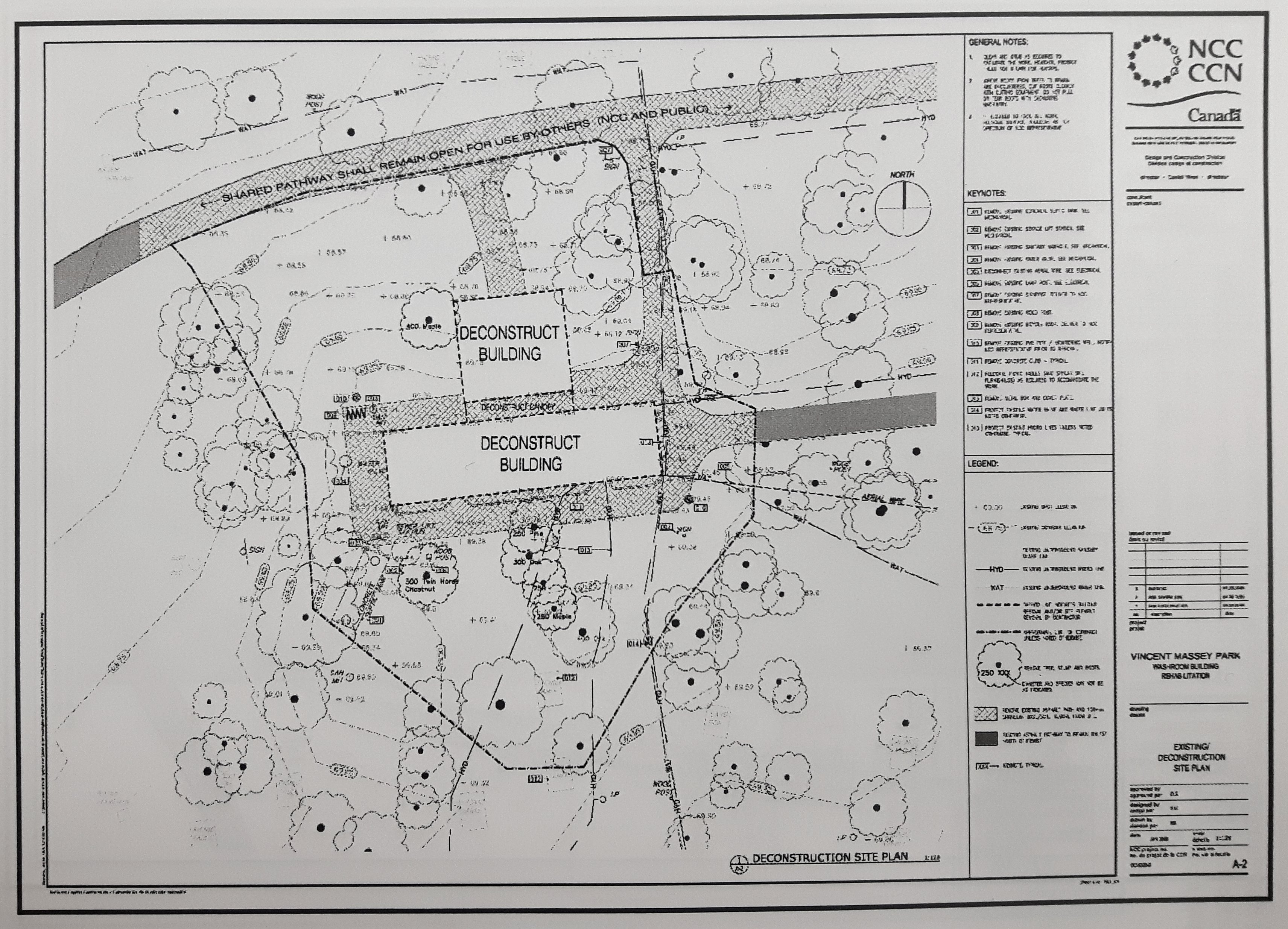

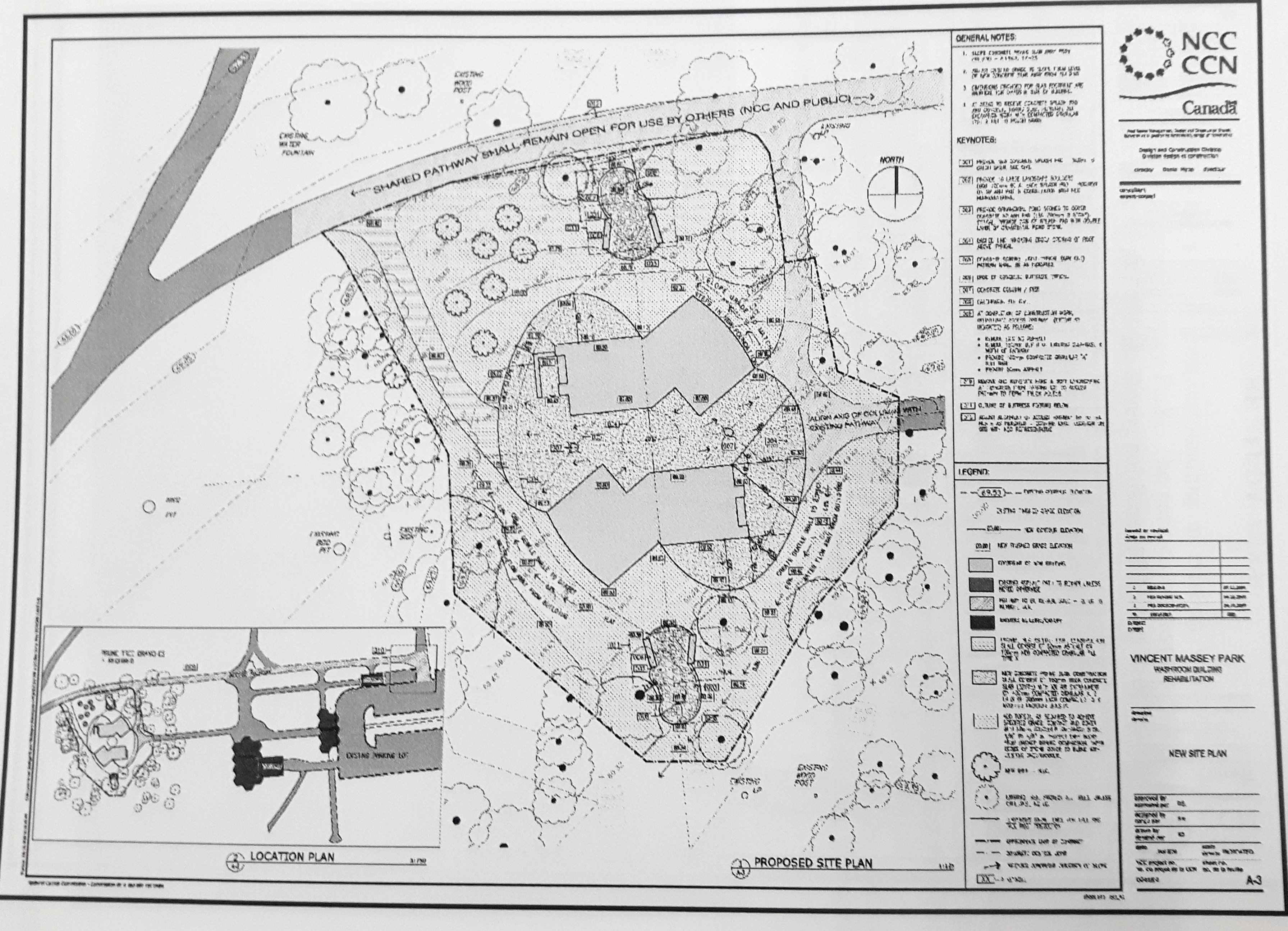

The washroom building was eventually deconstructed and replaced by a large beech leaf shaped structure, serving its original purpose as washrooms. Deconstruction refers to the disassembling of a building, so as to use it in another project. Signs are placed as educational and visual guides to understand the history of the park, and to inform the public about sustainable design initiatives.

The term ‘biophilia’ was coined by an American biologist, author and researcher Edward O. Wilson in 1984. He defined it as “the urge to affiliate with other forms of life” (Wilson, 1984). Today, ‘biophilic design’ refers to “…the deliberate attempt to translate an understanding of the inherent human affinity to affiliate with natural systems and processes… into the design of the built environment.” (Kellert, 2008) Since the term was first introduced in 1984, Hart Massey’s structures had not been referred to as biophilic, but possibly instead ‘organic’.

The Oxford Dictionary of Architecture loosely defines ‘organic architecture’, explaining that it has been used to describe so many contradictory styles that it may as well not be defined. However, the main associations of the term are linked to a natural order of design, evolving without an imposed, predetermined plan (Curl and Wilson, 2015).

TIMELINE

“…Ottawa’s park system was strongly shaped by the presence and activities of the Ottawa Improvement Commission and the Federal District Commission – federal government bodies responsible for development and maintenance of lands and buildings on federally-owned land in the national capital region” (Von Baeyer, 1993).

| Pre-1867 | Algonquin Anishinaabe traditional uses of the land. “Heron, Algonquin and Mississaugas travelled and hunted through the area”(Von Baeyer, 1993). The area consisted of forests and swampland. |

| Early colonial period | The area of Vincent Massey Park and Hogs Back was covered in beech, hemlock and cedar. This was cut down and the area was cleared. |

| 1899 | Wilfrid Laurier established the Ottawa Improvement Commission (OIC) to “transform Ottawa into a world-class capital city.” (Von Baeyer, 1993) |

| 1903 | Frederick Todd report for the OIC “city beautification plan”. |

| 1927 | Mackenzie King meets Jacques Gréber who was a French town planner |

| 1950 | Gréber presents his report, which emphasizes Ottawa’s requirement to develop green-space and urban parks, and to be surrounded by a greenbelt. Greber Plan is initiated. |

| 1952 | Vincent Massey is Governor General of Canada (The Governor General of Canada, n.d.) |

| 1951 – 1971 | Hart Massey architect in practice (NCC, n.d., 3) |

| 1958 | Hog’s Back Park and Picnic Grounds officially opens, Hart Massey’s Pavilions win silver medal in prestigious Massey Awards |

| 1959 | “Hog’s Back Picnic Grounds” named Vincent Massey Park, upon Vincent Massey’s consent.

National Capital Commission (NCC) was formed. |

| 1968 | Centennial bandstand opened to the public |

| 1990 | Introduction of paid parking to Vincent Massey Park |

| 1992 | Increased planting of native species of trees and shrubs |

| 1992 – 2011 | Pavilions were painted green and white |

| 2012 | Rehabilitation of Hart Massey’s pavilions, deconstruction of old bathrooms, construction of ‘beech’ shaped new bathroom |

Top: Plan for deconstruction of old washroom unit.

Right: Plan for new construction of washroom unit.

National Capital Commission. Retrieved from Past Recovery Archaeological Services. (Received by NCC on 10 September 2009). Stage 2 Archaeological Assessment of the Washroom Building Rehabilitation.

STAKEHOLDERS

Organizations:

- Historically, Jacques Gréber, Vincent Massey, Hart Massey and the National Capital Commission may be the most important figures associated with shaping the park grounds.

- The NCC has been the most dominant organization in protecting and preserving the park till present day. Additionally, they were responsible for the deconstruction of the original washroom buildings and the construction of the beech leaf shaped new bathroom.

- Parks Canada’s Federal Heritage Building Review Office (FHBRO) involved in the heritage designation of federal properties and reviews of projects (Parks Canada, 2008).

Consultants

- Edward J. Cuhaci and Associates Architects Inc. was responsible for the rehabilitation of Hart Massey’s pavilions in 2012. (Edward J. Cuhaci, n.d.)

- Engineers for washroom project – Cleland Jardine Engineering (NCC, n.d.)

- Consultants for washroom project – Genivar Consulting Group (NCC, n.d.)

Users:

The Ottawa River rivershed is the unceded territory of the Algonquin Anishinaabe.

The park is used by a wide variety of Ottawa residents today, including:

- Carleton University students, especially in the biology department, use it to undertake experiments and research (Past Recovery, 2009, 124).

- Cyclists are the most prominent users of the park, as the Rideau River Eastern bike path traverses beside the Rideau River and through the park.

- Employees who work at neighbouring buildings such as the Edward Drake building and Canada Post may use the park frequently.

- Bird watching groups were also a category of the users of the park (Past Recovery, 2009, 124).

- The Summer Solstice brings together people from diverse indigenous cultures, featuring powwows, Elders teachings, music and other activities (Wilson, 2014).

HERITAGE

Natural heritage: The city beautification plan and Greber plan introduced in 1903 and 1950, respectively, were important planning projects undertaken by the city of Ottawa. The planning that led to the creation of Vincent Massey Park is still intact and visible in the park to this day. Apart from a rise in planting of native trees and shrubs in the 1990s, no other dramatic changes have been made.

Cultural heritage: This includes the buildings and site design, the historic associations and uses of the land to celebrate indigenous connections.

- Buildings and site design: The bus shelter built by Hart Massey is a federal heritage designated “building” due to its historical, architectural and environmental value. The historical values stem from the Greber plan, the legacy of Vincent Massey, as well as his son. Hart Massey was an important, innovative designer who was one of the architects responsible for bringing post-war styles such as the international style and ideas from the Bauhaus movement to Ottawa. (NCC, n.d., 3)

- In terms of architectural value, the bus shelter is praised for its simple and minimalistic appearance. It is a clear example of ‘form follows function’ and draws inspiration from Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion, as is explained on the signage in the park.

“Architect Hart Massey designed the building as a pure, uncompromised expression of his ideals as a modernist. As such, it is a very good example of his work. It was undertaken early in his career, and was widely published having been among the grouping of four park buildings awarded a silver medal in 1958 from the Massey Awards for Architecture, the highest architectural honour at that time.” (Parks Canada, 2008)

- Its environmental value also lies in its minimalistic approach. The design strips the bus shelter down to merely its function, in a non-intrusive manner to the surrounding environment. (Parks Canada, 2008)

- The Massey Family is an important family name in Canada. Vincent Massey, the 18th Governor General of Canada, was the first to be Canadian-born. After him, a tradition was begun for every Governor General to be a Canadian citizen. His son, Hart, was the one to create the pavilions at Vincent Massey Park. The conservation of these pavilions, as well as the structure of the park, carries on the legacies of both father and son. (The Governor General of Canada, n.d.)

As mentioned previously, the park is today also used for the Summer Solstice festival, which celebrates indigenous cultures. While the NCC allows permits for whomever wants to hold their events at the park, there are hardly any events ever observed at the park apart from the Summer Solstice festival. This is significant in pushing forward an affirmative position for the indigenous cultures that reside in Ottawa. (Wilson, 2014)

SUSTAINABILITY

Environmental Sustainability: Historically the land had been cleared of much of its tree population. However, Vincent Massey Park has retained most of its natural environment since its official opening in 1958. In this way, the park continues its original vision from the implementation of the Gréber Plan. The modernist pavilions from 1958 were constructed with sustainable ideals in mind. “The contractors bidding on the buildings were advised that ‘special attention must be paid to preservation of trees and other natural features’” (Von Baeyer, 1993, 33).

The new washroom buildings introduced to the park in 2012 are a key element of the current approach to sustainability. Features in the design include

- Using 95% of the material from the previous structures. Also important to note is the use of materials for the new washroom buildings. All materials were sourced from within an 800km radius with the exception of beetle-damaged pine from British Columbia. The beetle-damaged pine however, if not used, would have been an environmental loss (NCC, n.d., 7).

- Site protection “Vincent Massey Park is more than 50 years old, and some vegetation and trees have failed over the years in the face of intensive public use. The new building was sited to protect existing trees” (NCC, n.d., 5).

Livability (Socio-environmental sustainability): The pavilions interact with the surrounding environment in a way that bridges the built and natural world through their biophilic design.

- Hart Massey’s original pavilions, for example, were designed to mimic the trunks and branches of surrounding trees, its roof’s undersides mimicking the fall colours.

- The new washroom building, shaped like a beech leaf, informs the public about the area’s native species.

- Signs in the park in front of the pavilions inform the public on how to interact with them, encouraging visitors to listen to the rain fall on and trickle down the beech leaf, to use their senses to guide them in learning about sustainable design.

- ‘Seeing the light’ refers to the use of translucent materials in the building, letting in daylight.

- These prompts are reminiscent of gardens that engage the five senses, as opposed to ornamental gardens. These invite visitors and interact with them, rather than remaining static displays.

Image above shows the sign placed in front of the new washroom building. Photo by Sampoorna Bhattacharya, taken in November 2017.

Social sustainability: The bike paths through the park give cyclists, roller-skaters, pedestrians etc. a refreshing break from the busy and loud city. The bike paths provide easy access to other nearby parks such as Mooney’s Bay and Hog’s Back falls. The ability to easily walk between a beach, a waterfall and a quiet forest-like area invites people to the park.

Economic sustainability:

- Equity (Socio-economic): The biological and ecological richness of Vincent Massey Park allows for hands-on practical research for Carleton students, enriching their university experience.

- Viability (enviro-economic): In reference to the newly erected washroom building, “Photo-voltaic cells installed on the roof of a nearby bus shelter harvest the sun’s energy to ensure that power drawn from the larger system – projected at 80mJ per square metre per year – is 100 percent compensated for by energy generated on site and returned to the provincial grid” (NCC, n.d., 7). This is an environmentally friendly consideration that also returns fiscally to the city.

- This new washroom building also is considerate in its use of materials. “The use of highly durable, long-lived materials in the building – aluminum roof shingles, terrazzo floors, concrete walls with steel panels – means both financial and environmental savings in terms of repairing and replacing elements over time” (NCC, n.d., 8).

MEASUREMENT: Assessing the Net-Zero energy of the new washroom building, the biophilic design of all structures, the heritage conservation through rehabilitation and deconstruction and the overall architectural achievement of the park structures will further our understanding of the park’s present status.

Zero Energy Certification through International Living Future Initiative: Net-Zero accreditation can be achieved through certification using a measured system managed by the International Living Future Institute (ILFI) known as “Zero Energy certification”. The new washroom building has passive ventilation, natural daylighting as well as rainwater capture and use. The building is not heated, does not use electric lighting during the day and uses motion sensors for light at night. These are all features that count towards Zero Energy certification, although more extensive measurement must be done in order to fill the criteria and evaluate the building (ILFI, 2017).

LEED: An unpublished information sheet from the NCC outlines the sustainable features of the new washroom project. These features line up well with the LEED criteria for certification, which include categories titled Location and Transportation, Sustainable Sites, Water Efficiency, Energy and Atmosphere, Materials and Resources, Indoor Environment Quality, Innovation and Regional Priority (USGBC, 2016).

The information in the sheet is summarized and arranged in the table below:

| Sustainable Site | Reduced site disturbance during construction.

Storm water management through bioswale and drywell. Reduced heat island effect by using high albedo roofing Reduced light pollution |

| Water Efficiency | Water use reduction through waterless urinals, low flow water closets and sinks, and water efficient native landscaping

Innovative rainwater harvesting technology. |

| Energy and Atmosphere | Optimized energy performance – innovative daylighting strategies for building interior to minimize electric lighting, energy efficient lighting, motion sensor for night, programmable astronomical lighting controls, energy efficient mechanical systems with controls to limit motors use, passive building ventilation, high insulation values (below grade)

Renewable Energy – Energy used by the building is targeted to be offset on an annual basis by on-site photovoltaic electricity generation, energy produced on site is derived from non-fossil fuel based renewable photovoltaics Systems Commissioning through a commissioning plan and proper building systems operation |

| Materials and Resources | Construction waste diversion from landfill by recycling, recycled content in construction material.

Durability – materials chosen to service long building life cycle Sustainable Forestry Initiative (SFI) Certified Douglas fir glulam |

| Indoor Environmental Quality | Indoor air quality plan – Passive ventilation, low VOC emitting materials, designed to create connection between indoors and outdoors, views for 100% of spaces, daylighting for 100% of spaces |

| Innovation & Design Process | Education through on site interpretive features

On-site green electricity generation Rain water harvesting – Reduced municipal water consumption building |

The Six Biophilic Elements and their Attributes: The ILFI also recently, in 2017, initiated the ‘Stephen R. Kellert Biophilic Design Award’. The award criteria include integration, expression, experience and evaluation of biophilic design. The six biophilic elements, environmental features, natural shapes and forms, natural patterns and processes, light and space, place-based relationships and evolved human-nature relationships must also be clearly present in the work, with each element supported through four attributes. These attributes are listed in detail in the first chapter of Kellert’s book, Biophilic design: the theory, science, and practice of bringing buildings to life, titled “Dimensions, Elements, and Attributes of Biophilic Design”. The table below displays Vincent Massey Park’s outcome in the fulfillment of the six biophilic elements.

| Environmental Features | Colour – The colours used are reflective of the fall colours in the park

Air – Natural ventilation flows through the new washroom building Water – rainwater is implemented in the design of the new washroom Sunlight – daylight is the main source of light in all buildings at the park |

| Natural Shapes and Forms | Botanical motifs – the representation of the beech leaf on the washroom building

Tree and columnar supports – the entrance pavilion implements representations of trees as columns Geomorphy – the structures mimic the landscape and geology in the park |

| Natural Patterns and Processes | Sensory variability – sounds, sights and feeling are all engaged with the new washroom building

Central focal point – the pathway from the entrance pavilion to the new washroom building creates a central space in the park Transitional spaces |

| Light and Space | Natural light

Reflected light – bright walls reflect light, as seen in the diagram Inside-outside spaces |

| Place-based relationships | Historic/ecological connection to place – the beech leaf honours the native species of the park grounds

Landscape features that define building form Avoiding placelessness – the structures integrate well with their natural surroundings |

| Evolved human-nature relationships | Curiosity and enticement – The signs with educational information about the pavilions stimulate curiosity |

Built Heritage Conservation and the Standards and Guidelines: The Standards and Guidelines for the Conservation of Historic Places in Canada is a good resource for analyzing this project in terms of its rehabilitation works.

- For the bus shelter, standard 1 is the most appropriate: “Conserve the heritage value of an historic place. Do not remove, replace or substantially alter its intact or repairable character defining elements. Do not move a part of an historic place if its current location is a character-defining element.” The Bus Shelter has retained its character defining elements since its designation, as can be observed in its unaltered colour, form and location. Standard 7 is also applicable as it mentions “Use the gentlest means possible for any intervention. Respect heritage value when undertaking an intervention”. The only intervention that was done was the NCC’s addition of photovoltaic panels to the roof in 2011. They used the same colours, retaining the structure’s minimalistic quality. The panels are hard to notice and do not catch the onlooker’s attention.

- The other structures, Hart Massey’s entrance pavilion and the now deconstructed washrooms, were not recognized as heritage buildings but did undergo rehabilitation work.

- The entrance pavilion was rehabilitated by Ottawa based firm Edward J. Cuhaci and Associates Architects Inc. While not much evidence exists as to the integrity of the pavilions before the undertaking, it can be assumed to have been similar to the pavilion at the neighbouring Hog’s Back Park, which Cuhaci rehabilitated as well.

- Their website explains that they worked in accordance to the Standards and Guidelines, specifically standard 1. (Edward J. Cuhaci, n.d.). They describe necessary replacement of unoriginal, rotten or hazardous material. Like the Hart Massey pavilions, this one too, had been repainted green and white, masking the original bright colours, which were restored by the rehabilitation work.

“Massey’s hexagonal tree-form canopies have been carefully restored, and repainted in their 1950s orange and red colour scheme. A highly acclaimed modernist masterwork has been restored.” (Edward J. Cuhaci, n.d.)

The National Capital Commission intervention in the park was of the deconstruction of the previous washroom buildings and the addition of the large, beech-leaf shaped washroom won the ‘2012 City of Ottawa Architectural Conservation Awards’ award of merit for adaptive use.

Photo by Sampoorna Bhattacharya, taken November 2017.

REFERENCES

Reports and Policies:

- Parks Canada. (2011). The Standards and Guidelines for Conservation of Historic Places in Canada.

- Past Recovery Archaeological Services. (Received by NCC on 10 September 2009). Stage 2 Archaeological Assessment of the Washroom Building Rehabilitation. National Capital Commission.

- Von Baeyer, E.. (1993). Hog’s Back and Vincent Massey Parks Landscape History. National Capital Commission.

Books and articles:

- Curl, James S.; Wilson, Susan. (22 Oct 2015). Organic Architecture. Oxford Dictionary of Architecture (ed. 3). Retrieved from http://www.oxfordreference.com.

- Mador, M.; Kellert, S. R; Heerwagen, J.. (2008). Biophilic design: the theory, science, and practice of bringing buildings to life. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

- National Capital Commission. (n.d.). Park Pavilions Vincent Massey Park. Unpublished information sheets. Received from Stephen Robertson, Project Delivery Manager, NCC.

- National Capital Commission. (n.d.). Parks Services Pavilion Vincent Massey Park, Ottawa. Unpublished information sheets. Received from Stephen Robertson, Project Delivery Manager, NCC.

- National Capital Commission. (n.d.). Vincent Massey Park Service Pavilion. Unpublished project notes. Received from Stephen Robertson, Project Delivery Manager, NCC.

- Wilson, E.O. (1984). Biophilia. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

News articles:

- Wilson, J. (12 June 2014). Summer Solstice Aboriginal Arts Festival a feast for all senses. Retrieved from http://ottawacitizen.com/

Websites:

- Edward J Cuhaci and Associates Architects Inc.Vincent Massey Park Buildings Rehabilitation and Hog’s Back Park Building Rehabilitation. Retrieved from: http://www.cuhaci.com/index.php/projects/heritage

- Federal Heritage Buildings Review Office. (2008). Bus Shelter; Vincent Massey Park. Parks Canada. Retrieved from: http://www.pc.gc.ca/apps/dfhd/page_fhbro_eng.aspx?id=12712

- Governor General of Canada. The Right Honourable Charles Vincent Massey. Retreived from: http://archive.gg.ca/gg/fgg/bios/01/massey_e.asp

- International Living Future Institute. Biophilic Design Award and Zero Energy program. Retreived from https://living-future.org

- US Green Building Council (5 April 2016). Checklist: LEED v4 for Building Design and Construction. Retrieved from: https://www.usgbc.org/resources/leed-v4-building-design-and-construction-checklist

Banner photo by Sampoorna Bhattacharya, taken November 2017.