Sustainable Land Management: the St. Williams Forestry Station Number 1 and 2, Norfolk County, Ontario

Case Study prepared by WW, Carleton University

Keywords: forestry, land management, deforestation, desertification, agriculture

LESSONS LEARNED

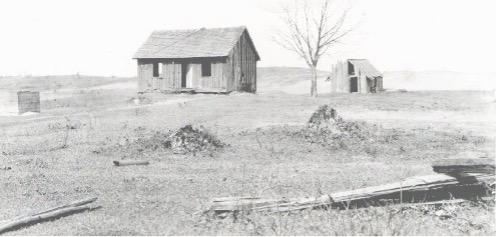

This case study focouses on the land and soil management that has resulted from St. Williams Forestry Station Number 1 and 2, Norfolk County, Ontario. Soil erosion has been a persistent issue in Norfolk County; following the era of timber men and ‘improvers’, much soil was swept off the Norfolk Sand Plain and deposited in Lake Erie. As farmers abandoned the degraded land, plants colonized the submerged sand. Encroaching on the open waters of Inner Bay, the extended marshlands today provide valuable habitat for aquatic life and the migrating waterfowl that feast on it, while the tracts of ‘planted wilderness’ found throughout the County are valued as important sites of leisure and recreation by the people of southern Ontario (Petrie & Knapton, 1999; Kreutzwiser, 1981). For the observer and historian, the cultural landscape of Norfolk County displays the tangible manifestations of economic and political processes alongside the remnants of a settler society that struggled to come to terms with farming on the sand. Conceptualizing landscape change as a continuum rather than discrete episodes allows us to expose the multitude and complexity of human responses to perceived environmental problems and earlier interventions in the land. Interventions in the landscape have a knack for outlasting the people who make decisions and undertake actions; it is necessary to embrace a longer historical perspective to understand the consequences of these changes and the manner in which subsequent generations interpret and adjust to these conditions. Taking a longer historical perspective also highlights how natural phenomena, economic choices, government decisions, and the unexpected outcomes of human intervention all played a role in the creation of waste land in the Norfolk Sand Plain and its subsequent transformation into Canada’s tobacco production heartland.

PRESENTATION

This slideshow primarily focusing on the land and soil management practices resulting from the St. Williams Forestry Station in Norfolk County, Ontario, Canada was presented on November 28th, 2019.

DESCRIPTION

In 1670 French Missionaries Dollier de Casson and Brehaut de Galinee described the region of Norfolk County in present day Ontario as “the earthly paradise of Canada” (Zavitz, 1909). When European settlement of Norfolk began in approximately 1791, the “earthly paradise” of which Dollier and Galinee spoke of was gradually denuded of life in the name of settlement, agriculture, and timber harvesting. As soon as the forest soil disappeared from the sand, it became difficult to maintain the fertility, resulting in several hundred acres becoming waste lands. The land devastation resulting from settlement came to be remedied through the establishment in 1908 of the St. Williams Forestry Station in 1908. The station is located at 885 Highway 24 West, St. Williams, Ontario. When the station was developed, five key pillars were at the core of the activities of the site:

- Stabilize the sand plain to prevent desertification

- Reforestation of abandoned farmland and wasteland

- Educating farmers about forestry, good forestry practices, and inter-relations between forestry and agriculture

- Establishment of woodlots and windbreaks

- Cultural hub for residents to interact with and understand forestry

Over time, the station transformed Norfolk County from a wasteland to Ontario’s garden through the 5 pillars stated above. The system of reforestation developed by the station succeeded in halting erosion, stabilized the sand plain, and provided a haven for wildlife, along with allowing for agriculture to thrive (Boutin et al., 1999). Landowners were encouraged to plant wind barriers as an inexpensive and effective way of protecting their fields from wind erosion using free seedlings distributed by the Provincial Forestry Station. Still today, observers of the Norfolk landscape will find fields divided by windbreaks into two or three long narrow strips.

Current pressures – to be completed.

TIMELINE

Below is the timeline for the site, where significant and important milestones have been identified. Intermediary time slots have been identified and outlined based on the respective Superintendent of the Forestry Station during that period. NB. From 1954 to 1969 multiple Superintendents were in place .

| DATE | EVENT |

| Early 1908 | Report Report by Edmund Zavitz titled “Report on Waste Lands of Southern Ontario 1908” (Barrett, 2008) |

| July 1908 | Founding of the St. Williams Forestry Station by Edmund Zavitz, Walter McCall, and Arthur Pratt (Barrett, 2008) |

| 1912 | First planting of white pine trees (Barrett, 2008) |

| 1913 – 1953: Frank Newman Era | Development, expansion, and creation of forestry practices (Barrett, 2008) Becoming a cultural mecca and community hub (Barrett, 2008) Education programs of farmers and landowners created and implemented (Barrett, 2008) Strengthening of forestry practices in the province (Barrett, 2008) |

| 1925 | 27,000 Acres reforested (Barrett, 2008) |

| 1945 | 140,000 Acres reforested (Barrett, 2008) |

| 1954 – 1969: Establishment and Production | Production rapidly increased (Barrett, 2008) Site became a staple in the community and a destination location for gatherings (Barrett, 2008) Education, outreach, and forestry programs expanded and enhanced (Barrett, 2008) |

| 1965 | 380,000 acres reforested; 7,000 acres being reforested annually (Barrett, 2008) |

| 1969 – 1983: Rolf Laupert Era | Modernization of the plantation processes (Barrett, 2008) Plantation processing and planting equipment created (Barrett, 2008) Enhanced measures to protect original plantation and woodlots (Barrett, 2008) |

| 1983 – 1990: Dolf Wynia Era | Modernization of the station and the practices (Barrett, 2008) |

| 1990 – Present | Privatization of the Forestry Station by the Province of Ontario, currently operated by St. Williams Nursery and Ecology Center (Barrett, 2008) |

| 2008 | Norfolk County designated Forest Capital of Canada (Canadian Forestry Association, 2008) Establishment of the Canada’s First Forestry Station Interpretive Center (Barrett, 2008) |

| 2007 | Norfolk County Heritage Designation of the Interpretive Center building (Barrett, 2008) |

| 2016 | Designated an Amazing Place through the Long Point World Biosphere Reserve (Amazing Places, 2016) |

| 2018 | Induction into the Norfolk County Agricultural Hall of Fame (Ball, 2018) |

STAKEHOLDERS

Primary Owners

- St. Williams Nursery and Ecology Center

- Province of Ontario

- Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry

Government

- Municipality of Norfolk County

- Norfolk County Heritage and Culture Department

- Federal government does not, nor did it have a role in the operations of the nursery as land management is a mandate of the Provincial or Territorial Government

Community

- People of Norfolk County

- Farmers and Agricultural Employees

- Six Nations of the Grand River

Groups and Organizations

- Ontario Heritage Trust

- Forest History Society of Ontario

- Long Point World Biosphere Reserve

- St. Williams Conservation Reserve (SWCR)

- Port Rowan / South Walsingham Heritage Association

- Royal Canadian Legion of Ontario

HERITAGE

The heritage values of St. Williams Forestry Station reside within the five key pillars identified above. In recognition of these pillars, many organizations have bestowed official designations on the site, citing one or more of the pillars. Through each designation both natural and cultural heritage comes to light.

Natural heritage: The areas which felt the impact of the St. Williams Forestry Station stretch throughout Norfolk County through the diverse methods developed to revert the impacts of deforestation. Through the activities of the station in the reforestation of Norfolk County, the provincial government succeeded in converting degraded land into productive forests and farmland under scientific management and affected the functioning of its ecological systems (Niewójt, 2007). Reforestation helped to stabilize the drifting sands throughout the region, regulated stream flows, decreased surface water run-off and the likelihood of flooding, provided additional wildlife habitat, and allowed agriculture to flourish in an environment where nothing previously could be grown, forming a defining aspect of the natural heritage of the site. This is reflected through Norfolk boasting the highest ecological diversity of animals, plants and natural habitats in Canada. Amidst fertile agricultural fields, rural hamlets and towns, and industrial sites, Norfolk now has the highest percentage of forested land in Southwestern Ontario, estimated at around 27%. (Solymar, Kanter, & May, 2008). In 2008 Norfolk was designated the Forest Capital of Canada by the Canadian Forestry Association. In further celebrating the site the Forestry Station was inducted into the Norfolk County Agricultural Hall of Fame due to the work of the station allowing agriculture to thrive into the modern day, with the site also obtaining the title of an “Amazing Place” within the Long Point World Biosphere Reserve.

The continued existence of the original 1912 plantation of white pines stands as a prominent element marking the site’s values. A significant component was the site’s role in the genesis of a scientific approach to tree seedling production and Ontario’s forest renewal programs (Canadian Forestry Association, 2008). The land on which the station itself sits, once considered “waste land,” is today described as being…

“provincially and nationally important for the conservation of biological diversity and natural heritage. It is a core component of a series of significant conservation lands located in Norfolk County. SWCR supports one of the largest remaining, although degraded, oak savannas in Canada, a globally threatened vegetation community. Ninety species of provincially rare flora and fauna have been recorded within SWCR, plus many regional rarities. The combined diversity of oak savanna, Carolinian forests, and wetland habitats support one of the highest remaining concentrations of species at risk in Ontario and Canada.” (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, 2005)

Cultural heritage: The primary attribute of cultural heritage of the site is its embodiment of the rich history of reforestation related to being the first forestry station in Canada. Further to that the tree seedlings produced at this forest station and in its demonstration forests played a major role in the environmental conservation and soil stabilization efforts in southern Ontario (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, 2005). A component which bolsters the cultural heritage of the site is the existence of an Interpretive Center which celebrates the heritage of the site, interpreting natural and human heritage of the St. Williams Forestry Station through artifacts and surrounding exterior spaces. This includes exhibits, guided interpretation, and educational programs. The Management Plan of SWCT also identifies the potential for archaeological artifacts and sites on the plantation grounds and an abundance of archaeological sites in the region ranging in age. The educational and cultural shift of the population of Norfolk County from exploiting to caretaking environment is also a cultural legacy.

SUSTAINABILITY

Environmental sustainability: As deforestation impacted the financial well-being of agriculturalists and foresters, steps were taken to replenish existing woodlands (Dunkin, 2008). Following the establishment of the station, over seven million seedlings were planted in Norfolk County during the 1920s alone (Kuhlberg, 1996, p. 138). By 1931, 20% of the land was under forest, and this was the highest proportion of woodland amongst the counties of southern Ontario (Parson, 1994, p. 245). Today, Norfolk continues to be a heavily wooded agricultural region, though the remnants of the drifting sands are still visible in the landscape. Provincial foresters did not expect the programme would restore the woodland that formerly existed in the region. Tree planting was expected to stave off further degradation and loss of topsoil. It was an ideal way to bring the deserted ‘waste lands’ under scientific management (Greig & Whillans, 1998).

Environmental sustainability is further enhanced through the existence of windbreaks, which proved to be the most effective and inexpensive means for protecting fields and agricultural practices from wind erosion. Windbreaks and woodlots, which were established on the worst wasteland areas, proved to be a haven for wildlife, generating ‘edge habitat’ supporting an abundance of insects and the birds (Niewójt, 2007). The site and reforestation is further connected to environmental sustainability through the combined diversity of oak savanna, Carolinian forests, and wetland habitats supporting one of the highest remaining concentrations of species at risk in Ontario and Canada (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, 2009). The provincial government’s programme of reforestation in Norfolk County succeeded in converting degraded land into productive forests under scientific management and affected the functioning of its ecological systems (Niewójt, 2007). Reforestation stabilized the drifting sands, regulated stream flows, decreased surface water run-off and the likelihood of flooding, and provided additional wildlife habitat (Kelly, 1974a, 1974b).

Socio-Cultural sustainability: During the periods of extensive reforestation large educational programs were developed to ensure proper forest management. Additionally, incentives were provided for forestry to encourage good practices, instilling a sense of ownership of the history and responsibility of the citizens as stewards of that heritage. This is reinforced through a quote from Edmund Zavitz when discussing Northumberland County wastelands where he said, “public sentiment in the united counties… was more advanced in the forestry question than anywhere else in the province, except possibly in Norfolk County.” (Dunkin, 2008). The educational activities to engage the community in forestry and the practices of good farm forestry is further reinforced by A.H. Richardson stated “the people of the community will be educated in the actual work of planting, because it will be they who will set out the trees. They will learn how to care for planting material…and how it should be handled in planting is the bests results are to be obtained. (Dunkin, 2008). Arbour Day, for example, endeavoured to ‘abolish long standing myths and misconceptions associated with nature and forests’ and promote the benefits of reforestation by the engaging school children in tree planting activities (Dunkin, 2008).

Economic sustainability: In 1914, the landscape of Norfolk County had come to represent poverty and hardship, and the land was littered with derelict farms, untended fields and shifting dunes of sand (McIlwraith, 1997). Foresters estimated that 10,000 acres of ‘sub-marginal’ land in the county could be transformed into economically viable forests or converted into ‘‘regions of beauty available for the recreation of residents and the enjoyment of visitors’’ (Zavitz, 1909, p. 6, 1947, p. 180). During that time and since the economics of forestry has been framed in the way stated prior, however a less investigated aspect of economic sustainability for forestry and agriculture is through agroforestry. Agroforestry is the land-use systems where trees are deliberately used on the same land-management units as agricultural crops, in some arrangement or sequence, like windbreak or woodlots (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2015). Through the concept of agroforestry, it can be seen the systems provide multiple outputs, potentially reducing risk and increasing income while also purportedly producing more ecosystem services than conventional agriculture (Mercer, Frey, & Cubbage, 2014) However, more research must take place on the economics of the St. Williams Forestry Station.

MEASUREMENT

Evaluation of the St. Williams Forestry Station and the activities it conducted considers two factors:

UN Sustainability Development Goal 15

| Measure | How the project/policy/place does |

| Target 15.1: By 2020, ensure the conservation, restoration and sustainable use of terrestrial and inland freshwater ecosystems and their services, in particular forests, wetlands, mountains and drylands, in line with obligations under international agreements (United Nations Division for Sustainable Development Goals, 2015) | The work of the forestry station ensured the conservation of freshwater, through forestry and reforestation as described in sections above. In turn this allowed for the preservation of waterways. This was accomplished through the stabilization of soil. For this to be maintained good forestry practices must be undertaken and maintained. |

| Target 15.2: By 2020, promote the implementation of sustainable management of all types of forests, halt deforestation, restore degraded forests and substantially increase afforestation and reforestation globally(United Nations Division for Sustainable Development Goals, 2015) | The work of the forestry station halted deforestation, restored degraded forests, and substantially increased afforestation across Norfolk County. This aspect formulated the core of the station and the key activity of the site. For this target to continue into present day a sound practice of reforestation and afforestation must be maintained for this to remain as true in the region. |

| Target 15.3: By 2030, combat desertification, restore degraded land and soil, including land affected by desertification, drought and floods, and strive to achieve a land degradation-neutral world (United Nations Division for Sustainable Development Goals, 2015) | Desertification and the restoration of degraded land and soil was one of the key pillars to the activities of the station, which was achieved throughout Norfolk, with the impacts still seen to this day. However, for the impacts of the Forestry Station to continue to be in effect, what was implemented by the station much be retained. |

IUCN Protected Areas Category VI: Protected area with sustainable use of natural resources

| Measures | How the project/policy/place does |

| To promote sustainable use of natural resources, considering ecological, economic and social dimensions (International Union for Conservation of Nature, 2019) | Education formed a key component to the activities of the station to ensure the longevity of interventions taken and a future for forestry within agriculture for the sustainable use of resources. Since privatization of the forestry system, education about forestry has diminished, resulting in people not understanding the connections between forestry and agriculture, favouring other interests like development. |

| To facilitate inter-generational security for local communities’ livelihoods – therefore ensuring that such livelihoods are sustainable (International Union for Conservation of Nature, 2019) | Agriculture in Norfolk county has come to be highly adaptive in the types of crops produced in the region from the soil. However, understanding of the adaptations that took place in previous generation is being lost, reducing the security in livelihood. |

| To integrate other cultural approaches, belief systems and world-views within a range of social and economic approaches to nature conservation (International Union for Conservation of Nature, 2019) | A vast array of techniques, cultural approaches, belief systems, and world views have been considered in the approach to reforestation, however with limited or no engagement with Indigenous peoples. |

| To contribute to developing and/or maintaining a more balanced relationship between humans and the rest of nature (International Union for Conservation of Nature, 2019) | The station ensured a balanced relationship between agricultural communities and nature, however due to privatization newer generations in the agriculture community are losing the understanding of the intrinsic connections between forestry and agriculture. |

Feature image of the Eastern White Pine plantation at the St. Williams Conservation Reserve in 2020. Credit: St. Williams Conservation Reserve.

REFERENCES

Books/Book chapters/Journal articles/Reports

- Ball, V. (2018, April 30). Bauke Vogelzang, Hellyer Ginseng, St. Williams Forestry Station inducted into Norfolk County Agricultural Hall of Fame. Simcoe Reformercoe Reformer, p. 2.

- Barrett, H. (2008). They Had a Dream: A History of the St. Williams Forestry Station. Aylmer, ON: The Aylmer Express Limited.

- Dunkin, J. (2008). A Forest for the Trees: Deforestation and Conservation Efforts in Northumberland County, Ontario 1870–1925. The International Journal of Regional and Local Studies, 4(1), 47–70. https://doi.org/10.1179/jrl.2008.4.1.47

- Greig, J. & Whillans, T. (1998) Restoring wilderness functions and the vicarious basis of ecological stewardship, Journal of Canadian Studies, 33(2), pp. 116 – 125.

- Kelly, K. (1974a) The changing attitude of farmers to forest in nineteenth century Ontario, Ontario Geography, 8, pp. 64 – 77.

- Kelly, K. (1974b) Damaged and efficient landscapes in rural and southern Ontario 1880 – 1900, Ontario History, 66(1), pp. 1 – 14.

- Kreutzwiser, R. (1981) The economic significance of the Long Point marsh, Lake Erie, as a recreational resource, Journal of Great Lakes Research, 7(2), pp. 105 – 110.

- Kuhlberg, M. (1996) Ontario’s nascent environmentalists: seeing the foresters for the trees in southern Ontario, 1919 – 29, Ontario History, 88(2), pp. 119 – 143.

- Mercer, D. E., Frey, G. E., & Cubbage, F. W. (2014). Economics of Agroforestry. Handbook of Forest Resource Economics, 188–209. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203105290

- McIlwraith, T. F. (1997) Looking for Old Ontario (Toronto: University of Toronto Press).

- Niewójt, L. (2007). From waste land to Canada’s tobacco production heartland: Landscape change in Norfolk County, Ontario. Landscape Research, 32(3), 355–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426390701318312

- Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. (2005). St . Williams Conservation Reserve Management Plan.

- Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. (2009). St. Williams Conservation Reserve 10-Year Operations Plan 2009-2018.

- Parson, H. E. (1994) Reforestation of agricultural land in Southern Ontario before 1931, Ontario History, 86(3), pp. 237 – 248.

- Petrie, S. A. & Knapton, R. W. (1999) Rapid increase and subsequent decline of Zebra and Quagga Mussels in Long Point Bay, Lake Erie: possible influence of waterfowl predation, Journal of Great Lakes Research, 25(4), pp. 772 – 782.

- Solymar, B., Kanter, M., & May, N. (2008). Caring for Nature in Norfolk Landowner Action in Carolinian Canada (P. Carson, M. Gartshore, A. Wynia, D. Reid, D. Wynia, S. Scheers, … R. Gould, Eds.). Carolinian Canada Coalition.

- Zavitz, E. J. (1909) Report on the Reforestation of Waste Lands in Southern Ontario, 1908 (Toronto: King’s Printer).

- Zavitz, E. J. (1947) Reforestation in Ontario, Canadian Geographical Journal, 34(4), pp. 156 – 180.

Websites

- Amazing Places. (2016). Canada’s 1st Forestry Station – Amazing Places. Long Point World Biosphere Reserve

- Canadian Forestry Association. (2008). FCC: Norfolk County 2008/09. Canadian Forestry Association

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2015). Agroforestry. Retrieved December 3, 2019, from Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations website: http://www.fao.org/forestry/agroforestry/80338/en/

- International Union for Conservation of Nature. (2019). Category VI: Protected area with sustainable use of natural resources. International Union for Conservation of Nature

- United Nations Division for Sustainable Development Goals. (2015). Sustainable Development Goal 15.