Adaptive Reuse of the Bata Shoe Factory and the Revival of Batawa

Case Study prepared by Jack Hollinger, Carleton University

Keywords: Industrial Heritage, Sustainable Development, Adaptive Reuse, Batawa, Small Town Rejuvenation

LESSONS LEARNED

The adaptive reuse of the Bata Shoe Factory provides the small town of Batawa with amenities not typically seen in small town Ontario: mixed income rental accommodation with recreational amenities for residents, a daycare and a community art space (LeBlanc; De Pauw). The finished project is evidence that communities, and buildings, are extremely adaptable. In recent decades Ontario has experienced massive declines in its manufacturing industries, and the accomplishment in Batawa lends a rejuvenation initiative as a model for other communities to follow (Davidson). Its success suggests that honouring local heritage can activate community members to get involved in a broader sustainability initiative (Carroon 2010).

Key to success of the Shoe Factory’s conversion was the consultation process. Dozens of meetings with varied parties resulted in a strong mandate to enact the resultant vision (De Pauw). This vision was brought to design by Sonja Bata, the project’s initiator and primary benefactor. Bata created a design for the Shoe Factory’s reuse by merging Batawa’s spirit of place with social and environmental responsibility.

Results reveal that economic, environmental and social actions act and react through community values, derived from Batawa’s origin story and function as a company town over several generations. When put to action these values aligned themselves nicely with sustainability initiatives articulated in literature and policy, and resulted in a rejuvenated building site that can act as foundation in the community’s transformation from industrial center to sustainable model.

The attached presentation offers a summation of the case study’s key points and provides a concise version of research outcomes. It was given in class on December 2, 2021.

DESCRIPTION

Recent literature recognizes existing buildings are increasingly seen as spatial reserves for users’ changed and novel needs, making adaptation a favourable option for both the environment and community. (Kaasalainen and Huuhka 1) The abandoned factory in Batawa makes an apt case study for repurposing a significant building based on community needs.

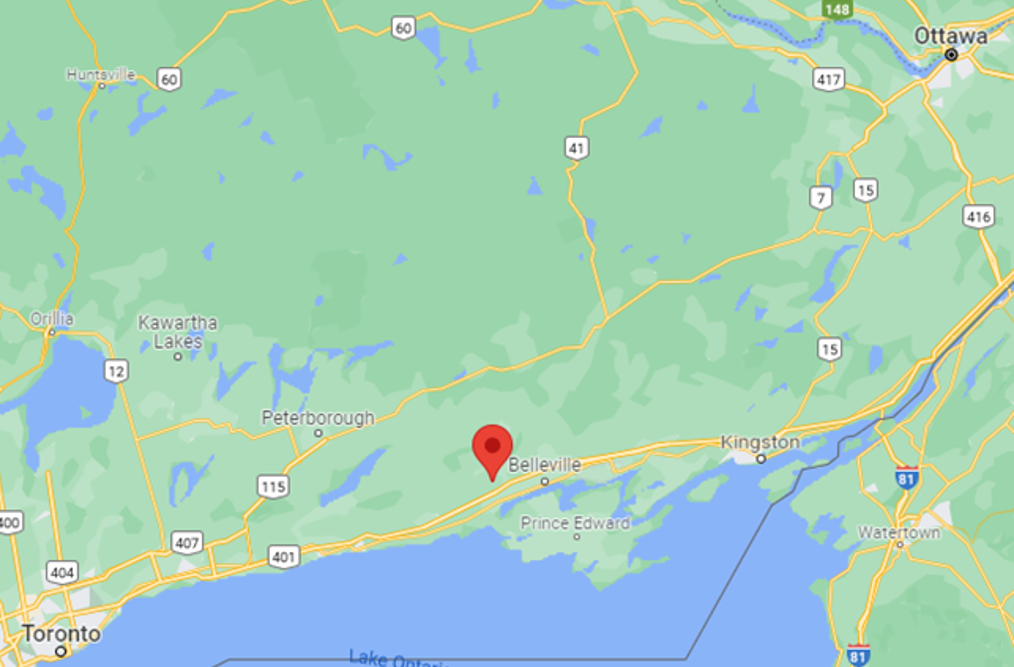

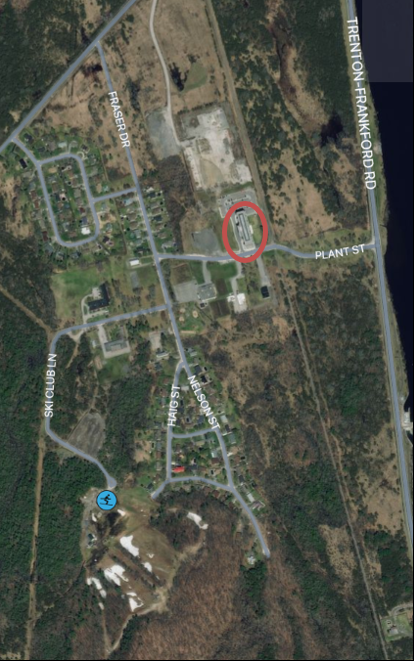

The Batawa Shoe Factory was the engineering headquarters of the world’s largest footwear manufacturer for over 50 years. Purpose-built as a standardized industrial town, Batawa’s social and economic livelihood revolved around the factory. The factory suffered successive cutbacks in the 1990’s, resulting in its closure in early 2000 (BDC). It was sold, but failed to ever regain its former significance, and by 2006 was vacant. The effect on Batawa was devastating. With social, environmental and economic sustainability at its core, the project (expressed at times throughout this investigation as both “Factory” and “Shoe Factory”) was the foundational first phase of what is an ongoing plan to re-grow the town (Nasmith).

The late Sonja Bata was the key driver in the factory conversion. It was her vision and uncompromising commitment to sustainability and community growth that suggest this project a model for other communities to follow. From its outset the project had three guiding principles:

- To maintain a light environmental footprint

- To fulfill a strong social mandate

- To honour the industrial heritage of the site (Canadian Architect)

Bata founded the Batawa Development Corporation in 2004 to fulfill these goals. She purchased the entire 1500-acre property in 2006 in order to build back a vibrant community where residents “could live close to nature yet be part of the modern economy” (De Pauw). The resultant mixed-use facility – with varied income rental accommodation, retail spaces, a daycare, meeting rooms, a community art gallery, a café and fitness facilities – is unique for a community of Batawa’s size. It successfully honours heritage, sharing Batawa’s origin story and resultant socio-cultural values, while building towards a sustainable future, by maintaining high standards for sustainable use and social responsibility.

The manufacturing decline of recent decades has left countless small towns in Ontario with vacant industrial buildings (Vecchio 339). Adaptive re-use of these buildings offers sustainable advantages to communities with development ambition: carbon sequestration in material re-use, population densification saving agricultural land from sprawling development and mixed-use planning (supporting a healthy life/work balance in a post-Covid home economy) among them. The example of the Bata Shoe Factory repurposement highlights a merging of environmental need, social responsibility, community values and economic reality that offers a positive path forward.

TIMELINE

Batawa – History of Site

- Pre-1783 Mississauga territory.

- 1783 Crawford’s Purchase gives title to the British Crown for loyalists arriving from the American Revolution.

- 1930s The Great Depression causes closure of businesses and decreased demand for the region’s agricultural goods. The region is devastated by unemployment and desperate for industrial investment (Cekota 50).

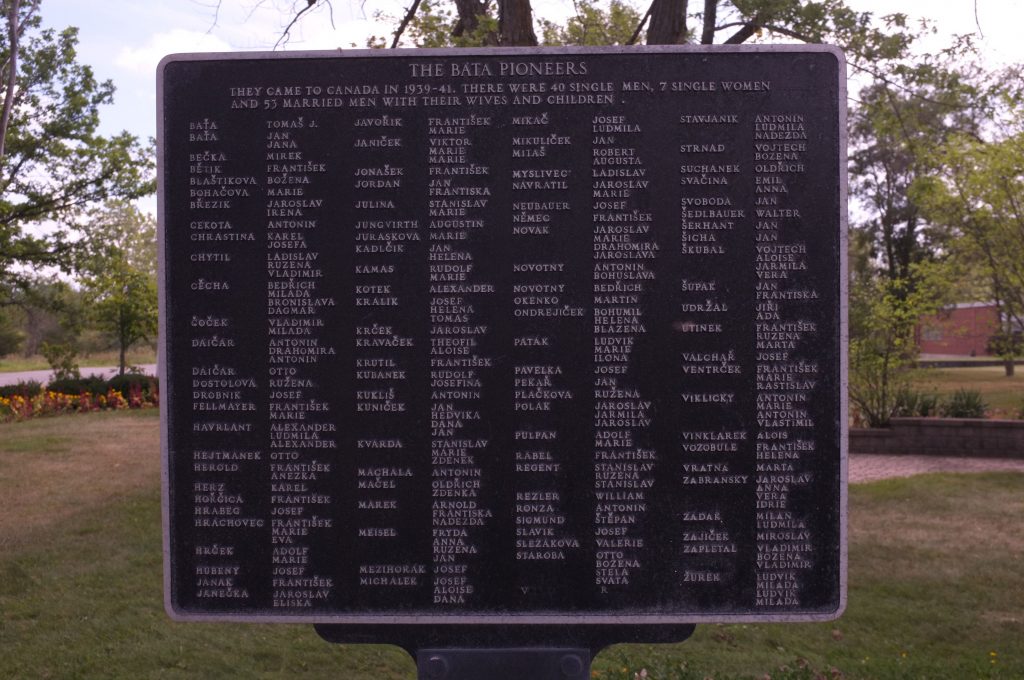

- 1939 Industrialist Tomas Bata arrives from Czechoslovakia, with 100 Czech families, and construction of Batawa begins. The town and factory are modelled on Zlin, Czechoslovakia, which was abandoned due to the Nazi advance. The newcomers are welcomed in Quinte (Cekota 39).

- 1944 Sonja Bata (wife of Tomas) arrives from Switzerland.

- 1990s Cutbacks and layoffs at the Shoe Factory. The community begins to atrophy.

- 2000 The factory closes. Revival as an industrial site is attempted, but is unsuccessful, and closes again after a few years.

- 2005-2011 The site is an abandoned industrial brownfield.

Timeline of Adaptive Reuse Project

- 2004 Sonja Bata forms the Batawa Development Corporation (BDC), with the expressed goal of rejuvenating the town.

- 2006 Sonja Bata purchases the entire 1500-acre facility property, including the abandoned factory building.

- 2007 RFA Planning Consultants produce a planning report outlining Sonja Bata’s vision: A Model for Sustainable Development in the Community of Batawa

- 2007-2012 Consultation with community members, interest groups, academics and government is ongoing and forms the basis for the eventual design of the Shoe Factory as the foundational piece in Batawa’s re-growth. These meetings prove invaluable to the design team.

- 2007 Municipal upgrades (water, sewage) are secured for future development.

- 2008 BDP Quadrangle and Dubbeldam Architecture and Design are hired to design and oversee the adaptive reuse.

- 2011 The Dalton Companyis hired as construction managers for the project, tasked with a unique procurement process prioritising local materials, trades and labour.

- 2013 Salvage work on the abandoned factory commences, with emphasis placed on material reuse and recycling (The Dalton Company).

- 2014 Structural rehabilitation and stabilization enables the plan for residential use (Ibid.).

- 2015-19 Construction is ongoing, including mechanicals, finishes and landscaping (Ibid.).

- 2018 Sonja Bata dies as the project nears completion.

- 2019 First occupancy.

- 2020-21 Multiple accolades and awards honour the project environmental and social sustainability (see: MEASUREMENT, below).

STAKEHOLDERS

Organizations:Consultation from wide-ranging groups (differing levels of government, governmental bodies, academics, special-interest groups, NGO’s and local citizens) convened for dozens of meetings to evaluate community needs. This process was instrumental in establishing the project’s overall direction and mandate (BDC). The resulting factory adaptive reuse is phase one in a broader overall plan for the rejuvenation of the community, including a business park, farmers market and further residential development. Only some of the parties are mentioned here:

- City of Quinte West

- Ontario Ministry of Environment

- Green Building Council

- Lower Trent Conservation Authority

- Carleton University

- Local Food Producers (Quinte Bee Keepers Association, Local Ontario, Hastings Federation of Agriculture, Batawa Maples)

- Economic Development Committees (City of Quinte; Counties of Hastings, Northumberland and Prince Edward)

Owners/users:The BDC is the sole owner of the property, renting the 47 residential units directly and leasing the retail and café spaces to local businesses. There is an integrated commitment to providing space for an art gallery, meeting venues, a daycare facility and park and greenspace open to the public (bdpquadrangle).

- Batwa Development Corporation

- Residents of 47 rental properties

- Lessees of 6 commercial properties

- Trenton Military Family Resource Centre

- Community of Batawa

- Batawa Lions Club

Consultants: Design work was coordinated by Sonja Bata (a trained architect and former Chair of the National Design Council). She remained involved until her death in 2018, and was uncompromising in her vision – evidenced by the fact that she contracted two of Canada’s premier architecture firms to see it through. The Dalton Company oversaw all construction, coordinating the geothermal energy system (the HIDI Group and Greer Galloway Group), reclamation of the concrete structure (Jablonsky, Ast and Partners) and a procurement process that prioritized local trades workers (The Dalton Company).

- Sonja Bata

- RFA Planning Consultants

- Dubbeldam Architecture + Design and BDP Quadrangle Architects

- Greer Galloway Group Inc. Engineers and Planners (Civil Engineer)

- The HIDI Group (Electrical/Mechanical Engineer)

- Jablonsky, Ast and Partners International (Structural Engineer)

- The Dalton Company

- Local tradespeople, material suppliers and laborers

HERITAGE

The definition of heritage is expanding and becoming more fluid, associating with present utility instead of solely emphasizing its physical features (Huuhka and Vestergaard 4). In many ways this project is a restoration – restoring the physical manifestation as representative of its original aesthetic, and restoring values representative of the original Czech immigrants and the sense of place created by their association to the Bata Shoe Factory.

Indigenous Heritage: The land that Batawa now resides on was Mississauga Territory at the time of European contact. It remained such until 1783, when a large tract of land was purchased from the Mississauga for loyalists (forced to leave the United States after the revolutionary war) in what is known as Crawford’s Purchase. Chief among the loyalists were the Haudenosaunee, who eventually settled just east of Batawa and founded the Tyendinaga Mohawk Reserve. Batawa and its factory sit on ceded territory (Boileau).

Cultural and Industrial heritage: Cultural heritage pertaining to the project is intrinsically tied to Batawa’s origin story and its industrial legacy.

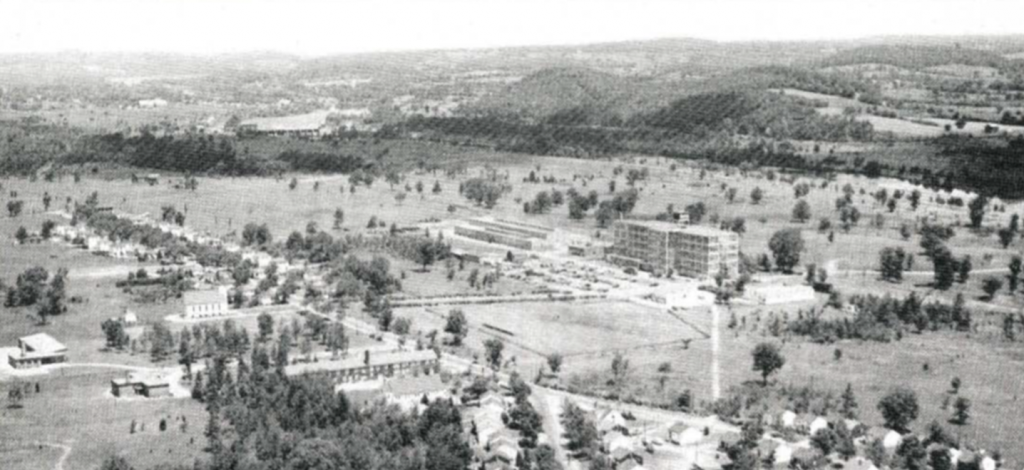

- The Bata Company was the largest footwear manufacturer in the world on the eve of WW2, headquartered in the industrial city it had constructed in Zlin, Czechoslovakia. As Hitler’s approach became immanent the Bata family decided to relocate some of its operations to Canada. The 1500-acre property was purchased in 1939, and within months 100 families from Zlin arrived to build and run the facility. These original immigrants are commemorated as pioneers in oral history, and in plaques and signage in public display outside the converted Shoe Factory. The name of Batawa is a combination of the owner’s name (Tomas Bata) and Ottawa, the capital of their new home (Cekota, 39).

- The factory workers and their families enthusiastically transplanted much of Zlin to Batawa. A ski hill was opened, many walking and ski trails established, a Catholic church, community center and sokol gymnasium were built, and many traditional festivals and gatherings were continued. Local residents accepted the immigrants enthusiastically, encouraged by employment opportunities associated with the burgeoning industry. The factory represented the lifeblood of the community, uniting immigrants and locals alike. Its demise in the 1990’s left residents nostalgic for its former prominence, and the sense of place it symbolized (Cekota 42).

- Batawa is an excellent example of a standardized industrial town. Town layout is based on the central location of the Shoe Factory, itself a significant example of the modern industrial style that revolutionized manufacturing across the western world in the early 20th century. It is the most significant building in the town, and the conservation of this significance was paramount to site rehabilitation.

- Sonja Bata aimed to create a community with similar values of inclusivity, family life and love of the outdoors that were evident in the Shoe Factory’s heyday (BDC). A rehabilitated building was key to the overall plan, both symbolically and for the life it would give to the community as a new edifice. The Bata Shoe Factory has no formal heritage designation.

Natural Heritage: The provincial Ministry of the Environment has designated parcels adjoining the factory site as an Area of Natural and Scientific Interest (ANSI). The Shoe Factory recognizes this significance with signage in partnership with the Lower Trent Conservation Authority, and protection has been incorporated by a network of trails promoting ecological educational (City of Quinte West 153).

SUSTAINABILITY

A growing understanding that built heritage contributes to sustainable development stems from the harnessing of energy and resources previously invested in existing constructions (ICOMOS, 6). From this vantage the conservation of the built environment is exceedingly sustainable, in environmental, economic and socio-cultural contexts.

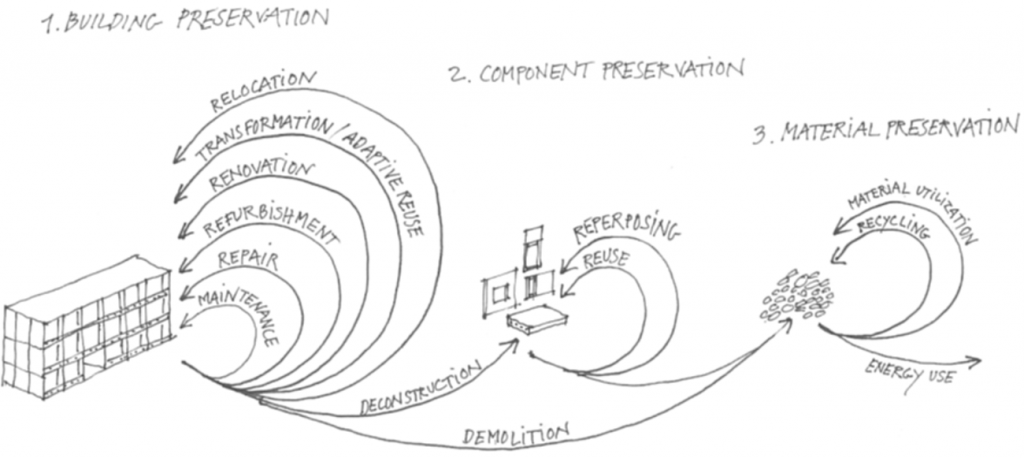

Environmental sustainability: Comprehensive life-cycle assessments of historic buildings conclude that there is a tremendous impact to the environment in new construction, and that its avoidance presents an eco-conscious approach to the environment (Athena Institute, 4). This ties in with new research applying the concept of a circular economy to built heritage (See image).

- Material Use: Having served its purpose as an industrial facility, the conversion of the factory building to modern usage demanded a thoughtful approach towards materials and waste. Through deconstruction many of the supplementary materials (ie.glazing) were salvaged for repurposing, and when demolition was necessary others (aluminum cladding, concrete) were recycled. (The Dalton Company) New building materials were sourced based on three criteria speaking to sustainability: long life-spans, durability and eco-friendly characteristics (SAB Magazine).

- Site ecology: The rehabilitation of the former parking lot that surrounded the building consisted of replacing the concrete surface, allowing more natural water management. Concrete was recycled into gravel and reused on site in both permeable parking surfaces and landscaping. Storm water on site is managed by a large bio-swale on green space. The grounds have been landscaped with drought resistant species and require no irrigation system.(SAB Magazine)

- Water, Energy, Air and Light: The geothermal energy system provides all heating and cooling, resulting in zero carbon emissions. No fossil fuels are consumed, save for those accounted for via electricity delivery. General building usage requires electricity only for pumps, lighting and general occupant consumption. All light and water are delivered through high efficiency LED lighting and low flow plumbing fixtures (bdpquadrangle).

- Indoor environmental quality (IEQ) was prioritized in design. Operable windows allow for ample natural light and ventilation. The selection of natural materials minimizes Volatile Organic Compounds (VOC’s).

Socio-cultural sustainability: Initiative towards social responsibility stemmed from the cultural ties between the original Czech immigrants the broader community. Having escaped a Nazi advance, the Czech’s embraced their new home with generosity and reverence. The existing community was appreciative of the opportunities represented in the factory associated with the immigrants, and welcomed them with open arms. This cultural fellowship was maintained and strengthened over years of production. It is this sense of place which Sonja Bata wished to capture in the adaptive reuse (BDP).

The incredibly thorough consultation process was inclusive and emphasized community and providing resources for locals. This process intimately bonded the community to the adaptive reuse, aligning with research which concludes that individuals participating in community have stronger ties to that community, with stronger feelings of connection and identification. (Landorf 466)

Community input resulted in numerous initiatives that were incorporated into the design of the adaptive reuse and which will contribute to social sustainability (SAB Magazine):

- Interior layout and inclusion of public space encourages young families and children to share the space with seniors (whether residents of the building or the community at large) and facilitates a blending of social, cultural and community values

- An in-house daycare presents opportunities for single parents and working families

- The art gallery, lecture/meeting rooms, retail shops and café allow for social and intellectual stimulation and growth

- Densification resulting from the 47-unit residential building encourages community interaction and conserves green spaces to be prioritized as outdoor playgrounds, walking trails with access to a community network of skating rinks and ski trails, and parks

Economic sustainability: The loss of the manufacturing facility was an enormous economic blow to Batawa. The BDC was formed in an attempt to find a viable path forward without an overarching industry supplying financial security. Several initiatives have carried over from the consultation process that aim to strengthen the town’s economy and offer residents a means of economic support (SAB Magazine).

- Hi-speed fibre internet service opens opportunities for growing a local knowledge-based work economy and gives residents the option to work remotely rather than commute to a workplace.

- Rental units ensure access to those who cannot afford home ownership and a more diverse community.

- The factory project is phase 1 of a larger plan, which includes a business park to further diversify the local economy.

During the construction process building materials and trades workers were sourced locally, when possible. The community-centered procurement plan optimized social and economic benefits for those living and working within a 100-mile radius of the site (Dalton).

As part of initial community consultations, a notable amount of information sharing educated local residents and community stakeholders on the short and long-term benefits of considering both a socially and environmentally sustainable strategy for this development. Visitors to the building receive an information package sharing the unique features and history of the building as well as best practices for a healthy building and healthy planet (BDC).

MEASUREMENT

The adaptive reuse strategy was selected based on evidence accrued through a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA). The National Research Council’s low-carbon assets through life cycle assessment (LCA²) initiative achieved a science-based approach to support the selection of materials and designs that offered the lowest carbon footprint (NRC). Although the LCA report could not be referenced directly for this Case Study, it is referred to in literature by The Dalton Company and SAB magazine as justification for adaptive reuse as the most sustainable approach for site regeneration. (Dalton, SAB)

The Canadian Green Building Awards, presented by Sustainable Architecture and Building magazine, recognize the best examples of sustainable, high-performance building design in Canada. It awarded The Bata Shoe Factory Revitalization project with its Residential (large) Award, stating that the “building is a model for increased housing density in a rural setting with the lightest impact on the environment and a focus on community and social sustainability.”(SAB) More information on the awards, including statistics on building performance, can be found here: https://sabmagazine.com/bata-shoe-factory-revitalization-batawa-on/

The Brownie Awards, presented by the Canadian Brownfields network, recognize the rehabilitation of brownfield sites into productive residential and commercial projects that contribute to the growth of healthy communities across Canada. The Bata Shoe Factory received the Brownie for best overall small project in 2020, noting the redevelopment was “the first phase of the late Sonja Bata’s vision for the revitalization of the town of Batawa.”(Brownie Awards 2020) Additional details on this award can be found here: https://www.canadianbrownfieldsnetwork.ca/brownfield-awards/brownies/2020-brownie-winners

Notable measures referenced in these awards include:

- The retention of the original structure represents a savings of 5,200 m³ of concrete and approximately 2 million kg of CO2 emissions – over 900 cement truck deliveries (Dalton)

- The geothermal system consists of 63 holes at a depth of 600 feet, supplying 100% of the buildings HVAC and producing no carbon emissions. (SAB)

- The adaptable reuse design strategy utilized in conjunction with an ongoing owner-management approach ensures the building will continue to service its new use for another 70+ years. (SAB)

Qualitative social sustainability analysis utilizes Chris Landorf’s evaluation criteria (Landorf, 466-470).

| Social Equity | Access to services, facilities and opportunities | The art gallery, daycare, and public spaces are all important components of social and community infrastructure |

| Social Coherence | Strength of networks, participation, identification and tolerance | The rejuvenation of the Shoe Factory strengthens identification with local heritage, resulting in greater social cohesion |

| Level of empowerment and accountability | The consulation process allowed for a clear vision with a strong social mandate. | |

| Basic Needs | Objective and subjective satisfaction of basic needs | High quality housing is approachable with rent, rather than own, approach; high speed internet offers economic opportunity; daycare allows for equitable participation in housing and employment |

There is strong alignment with four of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, indicating a strong foundation for the long-term sustainability of the project (United Nations “Agenda for Sustainable Development”).

| Goal, Targets and Indicators | Significant Characteristics | Shoe Factory Reuse Aligning Factors |

| Goal 7. Targets 7.2, 7.3 Indicators 7.2.1, 7.3.1 | renewable energy, improving energy efficiency | geothermal heating and cooling; high efficiency lighting and appliances; no fossil fuels |

| Goal 11. Target 11.3 Indicator 11.3.2 | citizen participation in urban planning and management | varied stakeholders had real influence in open planning process and creation of official development plan |

| Goal 12. Targets 12.4, 12.7 Indicators 12.4.2, 12.7.1 | limit hazardous waste, establish and maintain sustainable procurement | selection of natural, stable materials; procurement process prioritized the local economy |

| Goal 15. Target 15.3, 15.5 | restore degraded land and soil, halt loss of biodiversity | restoration of brownfield site; protection of ANSI; use of drought resistant native species |

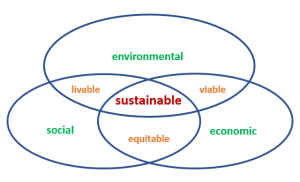

Berthold, et.al. (2015) consolidated common sustainability indicators and their ability to cover the environmental, economic, and sociocultural dimensions of urban heritage. Usage of their conceptualization of sustainable development offers valuable insight into the intersections of the traditional three pillars approach, and offers insight into the livability, viability and equity of the rejuvenated Shoe Factory (Berthold, et.al. 24).

| Intersecting Sustainability Pillars | Resulting Theme | Aligning Features from the Rejuvenated Factory |

| Environmental, Social | Livability | Emphasis on natural light, fresh air, outdoor green spaces, natural materials, green energy |

| Economic, Environmental | Viability | Densification in rural environment; fibre optic network geared towards remote work, investment in local food production |

| Social, Economic | Equitability | Rental units allow more equitable access; daycare helps working families, single parents; designed to be part of broader community |

In summation: The Bata Shoe Factory conversion performs admirably with regards to socio-cultural and environmental sustainability assessment, with factors in place for positive economic sustainability given time and next steps taken in the overall plan for Batawa. The project honours community values and ensures the building maintains its significance as a heritage landmark in Batawa.

WORKS CITED

Books/Book chapters/Journal articles

- Berthold, Étienne et.al. “Conceptualization of SD.” From “Using sustainability indicators for Urban Heritage Management: A review of 25 case studies.” International Journal of Heritage and Sustainable Development, Vol. 4, No. 1, 2015, pp.23-34.

- Carroon, Jean. “Buildings and Environmental Stewardship, Understanding the Issues.” Sustainable Preservation, Greening Existing Buildings. Wiley, 2010. pp.3-18.

- Cekota, Anthoy. The Battle of Home: Some Problems of Industrial Community. Toronto: MacMillan, 1944.

- Chan, Jacky, et al. “Potential Economic and Energy Impacts of Substituting Adaptive Reuse for New Building Construction: A Case Study of Ontario.” Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 259, Elsevier Ltd, 2020, p. 120939–.

- Della Spina, Lucia. “Adaptive Sustainable Reuse for Cultural Heritage: A Multiple Criteria Decision Aiding Approach Supporting Urban Development Processes.” Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland), vol. 12, no. 4, MDPI, 2020, p.1363–.

- Elefante, Carl, 2012 (2007), “The Greenest Building Is…One That Is Already Built,” Forum Journal: National Trust for Historic Preservation, 21.4. 67-72.

- Fairclough, Graham. “New Heritage Frontiers,” Heritage and Beyond. Ed. Council of Europe, 2009, p32-33.

- Huuhka, Satu, and Inge Vestergaard. “Building conservation and the circular economy: a theoretical consideration.” Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development, 2019.

- Landorf, Chris, 2011, “Evaluating social sustainability in historic urban environments.” International Journal of Heritage Studies, 17.5: 463-477.

- Kaasalainen, Tapio, and Satu Huuhka. “Existing apartment buildings as a spatial reserve for assisted living.” International Journal of Building Pathology and Adaptation, 2020.

- Pavitt, Jane. “The Bata Project: A Social and Industrial Experiment.” Twentieth Century Architecture (1994): 31-44.

- Ricketts, Shannon. “Batawa: An Experiment in International Standardization.” Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada. Bulletin, vol. 18, no. 3-4, 1993, pp. 80–87.

- Ross, Susan. “How Green Was Canadian Modernism, How Sustainable will it be?” Docomomo Journal, Canada Modern 38, 2008.

- Preservation Green Lab. The Greenest Building: Quantifying the Environmental Value of Building Reuse. Seattle: National Trust for Historic Preservation, 2011.

Policies and reports

- Athena Institute. “A Life Cycle Assessment Study of Embodied Effects for Existing Historic Buildings.” 2009. www.athenasmi.org/wp- content/uploads/2012/01/Athena_LCA_for_Existing_Historic_Buildings.pdf. Accessed Nov.10, 2021.

- Ballamingie, Dr. Patricia. Carleton University – BDC Collaboration: Combining scholarship and action to create a sustainable community. Batawa, March 26, 2009.

- Batawa Urban Agriculture Stakeholders Meeting. “Meeting Notes.” March 26, 2009.

- City of Quinte West. Official Plan City of Quinte West. July 17, 2013. quintewest.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Quinte-West-Official-Plan-Consolidated-to-Amendment-12-1.pdf.

- Davidson, Mitchell. “Small Towns, Big Opportunities.” StrategyCorp Institute of Public Policy and the Ontario Real Estate Association, 2021.

- ICOMOS. “The Future of Our Pasts: Engaging Cultural Heritage in Climate Action.” July1, 2019, https://indd.adobe.com/view/a9a551e3-3b23-4127-99fd-a7a80d91a29e. Accessed October 28, 2021.

- McConville, Megan. “Creating Equitable, Healthy and Sustainable Communities.” Environmental Protection Agency, 2013. www.epa.gov/dced/pdf/equitable-dev/equitable-development-report-508-011713b.pdf. Accessed November 2, 2021.

- Ontario Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change. “Record of Site Condition.” March 14, 2016. www.downloads.ene.gov.on.ca/files/besr/RSC%20221630.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2021.

- RFA Planning Consultant Inc. “A Model for Sustainable Development in the Community of Batawa.” Batawa Development Corporation, 2007.

- Vecchio, Marcello, and Godwin Arku. “Promoting Adaptive Reuse in Ontario: A Planning Policy Tool for Making the Best of Manufacturing Decline.” Urban Planning, vol. 5, no. 3, Cogitatio Press, 2020, pp. 338–50.

- United Nations. 2015. “Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.” www.sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld. Accessed November 15, 2021.

Websites

- BDC. 2021. “Batawa – beautiful by nature and design.” www.batawa.ca/index.php. Accessed 26 October 2021.

- “Bata Shoe Factory, Batawa, Ontario.” Canadian Architect, September 29, 2020. www.canadianarchitect.com/bata-shoe-factory/. Accessed November 1, 2021.

- bdpquadrangle. 2021. Bata Shoe Factory Wins Canadian Green Building Award. www.bdpquadrangle.com/ideas/blog/post/blog/2020/06/01/bata-shoe-factory-wins-canadian-green-building-award. Accessed October 28, 2021.

- Boileau, John. “Crawford Purchase”. The Canadian Encyclopedia, 19 October 2020, Historica Canada. www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/crawford-purchase. Accessed 06 December 2021.

- Brownie Awards 2020. “Best Small Project Winner – Bata Shoe Factory”. www.brownieawards.ca/2020-brownie-awards-winners/. Accessed November 1, 2021.

- Carleton University. “Carleton Contributes to Sustainable Community.” Ottawa Citizen, 28 June, 2009. www.ottawacitizen.com/news/local-news/carleton-contributes-to-sustainable-community. Accessed October 29, 2021.

- De Pauw, Carine. “Bata Shoe Factory Revitalization.” Sustainable Architecture and Building Magazine, 4 November, 2020. www.sabmagazine.com/bata-shoe-factory-revitalization-batawa-on/. Accessed October 28, 2021.

- Government of Ontario. “Map of Ontario treaties and reserves”. 28 July 2021. www.ontario.ca/page/map-ontario-treaties-and-reserves. Accessed October 27, 2021.

- Hamilton, Frank. “The Fabulous Shoemaker.” Maclean’s, 1 April, 1949. www.archive.macleans.ca/article/1949/4/1/the-fabulous-shoemaker. Accessed October 26, 2021.

- Hutchins, Aaron. “What’s killing rural Canada?” Maclean’s, September 1, 2018. www.archive.macleans.ca/article/2018/9/1/whats-killing-rural-canada. Accessed October 25, 2021.

- LeBlanc, Dave. “A Polished Update for a Former Shoe Factory; ARCHITOURIST.(Real Estate).” Globe and Mail, 2020, p. H2. www.theglobeandmail.com/real-estate/toronto/article-a-polished-update-for-a-former-shoe-factory/. Accessed October 24, 2021.

- Mendelson, R. “BDP Quadrangle Turns a Former Shoe Factory Into a Community Hub.” Green Building and Design, February 9, 2021. www.gbdmagazine.com/bdpquadrangle/. Accessed October 19, 2021.

- Nasmith, Catherine. ” Adaptive Re-use, Bata Shoe Factory, Batawa, Ontario.” Built Heritage News, 29 October, 2020. www.builtheritagenews.ca/newsletter.php?id=462#10. Accessed October 28, 2021.

- National Research Council of Canada. “Low-carbon assets through life cycle assessment initiative.” August 28, 2019. www.nrc.canada.ca/en/research-development/research-collaboration/programs/low-carbon-assets-through-life-cycle-assessment-initiative. Accessed November 6 2021.

- Our World Heritage. 2021. Sustainability Case Studies. www.ourworldheritage.org/s_cs/. Accessed November 1, 2021.

- “Reflecting on the Remarkable Construction Story of the Bata Shoe Factory”. The Dalton Company, January 29, 2020. www.daltonbuild.com/post/reflecting-on-the-remarkable-construction-story-of-the-bata-shoe-factory-part-two. Accessed November 3, 2021.

- SAB Magazine. “Green Building Awards 2020.” www.sabmagazine.com/awards/awards-winners-2020/. Accessed October 28, 2021.

- United Nations. “Agenda for Sustainable Development.”

Banner Image: Batawa in 2021. Photo: Susan Ross