Sustainable Neighbourhood Retrofit Action Plan: An integrated approach to neighbourhood-scale sustainability in Brampton, ON.

Case Study prepared by Christie Ellis Wong, Carleton University

Keywords: Sustainable Retrofits, Living Cities, Modern Heritage, Natural Heritage Systems, Suburban Neighbourhoods

LESSONS LEARNED

The Sustainable Neighbourhood Retrofit Action Plan (SNAP) model, and its application in County Court, Brampton (Ontario) demonstrates:

- The localization of sustainability objectives by applying a regional framework and utilizing existing policies and plans to develop and pursue community-specific targets;

- The operation of a multi-objective system, embedding numerous types of interests and goals under a broader framework of sustainability as envisioned in the ‘Living City’ model;

- The ways that social and environmental goals may be integrated or interrelated; and

- Application of sustainable interventions at the scale of the neighbourhood

The SNAP program presently being developed for the Bramalea neighbourhood in Brampton may be an opportunity to further develop:

- The integration of cultural and economic objectives within the SNAP model;

- Recognition and conservation of modern heritage within Brampton; and

- The simultaneous conservation of natural and cultural heritage in pursuit of holistic sustainability goals.

PRESENTATION

The following presentation was given on November 14th, 2019. Part of the scope of the case study project, the in-class presentation provided an interim opportunity to share a draft of the research and receive feedback to further the development of the study. It includes preliminary identification of heritage attributes of Brampton, and highlights some of the potential learning opportunities which may be provided by a study of the application of the Sustainable Neighbourhood Retrofit Action Program.

DESCRIPTION

Brampton relative to City of Toronto

Neighbourhoods within Brampton

Context maps showing the extents of the City of Brampton relative to the City of Toronto and the Pearson Airport. Closer scale context map showing neighbourhoods – approximating the locations of Heritage Conservation Districts in Brampton, (Main Street South and Churchville); as well as the postwar subdivision Bramalea. Brampton’s two SNAP neighbourhoods, County Court, and a future SNAP in Bramalea are indicated in pink. Base images from Google Maps, illustration added by Christie Ellis Wong.

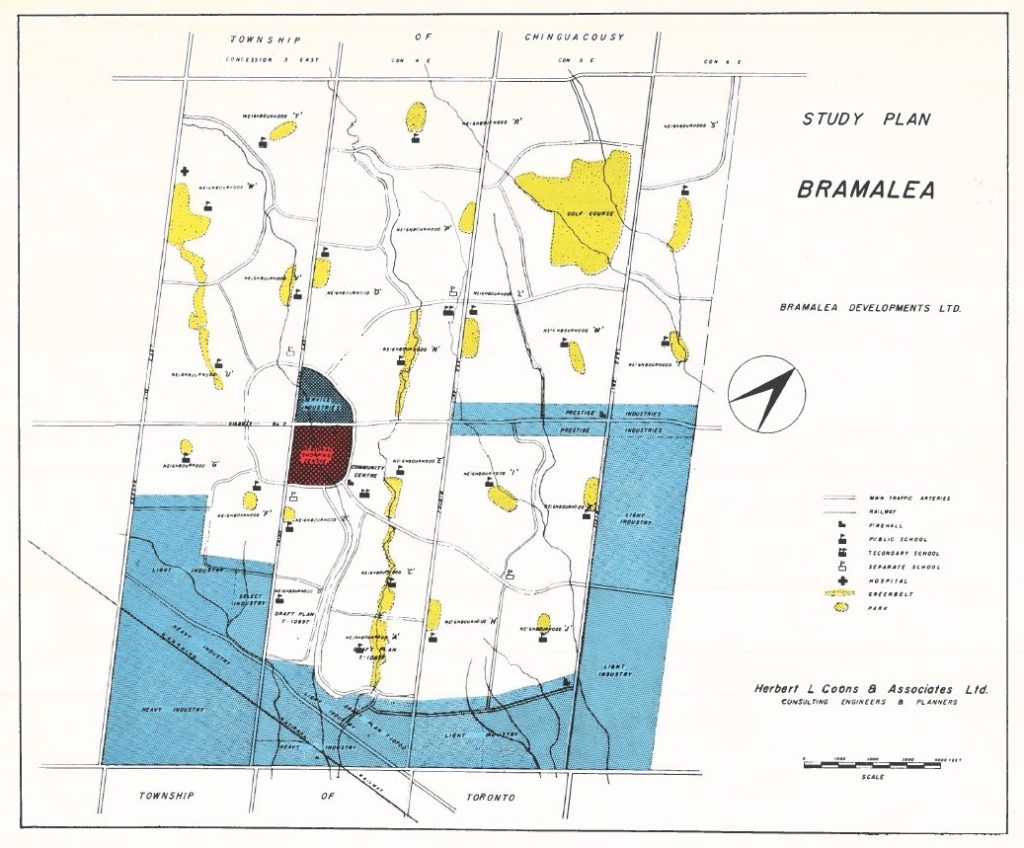

Brampton: Brampton is located within the Treaty Lands and Territory of the Mississaugas of the Credit. The arrival of British settlers to the area in the early nineteenth century “had weakened the Mississaugas’ traditional economy and had left them in a state of impoverishment and a rapidly declining population,” and led to the signing of the Ajetance Treaty (MCFN, n.d.). European settlement in Brampton dates from 1820, and much of the greater area of the city was built out in suburban development through the second half of the twentieth century. The neighbourhood of Bramalea, within Brampton has a unique history, as it was established as Canada’s first ‘satellite city’ in the late 1950s, making the neighbourhood a precedent for other suburban development which would occur across the country (City of Brampton, 2015, p. 5).

The Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA) and the Sustainable Neighbourhood Retrofit Action Program (SNAP): The Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA) was established in the post-war era, with the aim to “safeguard and enhance the health and well-being of watershed communities through the protection and restoration of the natural environment” (TRCA, n.d.). The vision of the TRCA is that of a “Living City” which integrates human settlement and the natural environment; the TRCA works in many areas throughout the Etobicoke and Mimico Creek Watersheds (TRCA, n.d.).

Logo of the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority, Retrieved from https://www.newswire.ca/news-releases/toronto-and-region-conservation-authority-announces-john-mackenzie-as-new-ceo-638082563.html

The Sustainable Neighbourhood Retrofit Action Program (SNAP) is one TRCA initiative aimed at helping communities to embody the Living City vision. The SNAP model implements projects at the scale of the neighbourhood and pursues measurable multi-objective goals. All SNAP programs are unique, but “share a common approach” and “use the existing social and economic conditions of the neighbourhood and guidance from bigger-picture plans and strategies as the basis for targets and key actions on public and private properties” (TRCA, n.d.).

SNAPs in Brampton: Among the early pilot neighbourhoods of the SNAP program is the County Court SNAP in Brampton. Since 2012, SNAP has expanded to include six neighbourhoods in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA). Brampton will be the first city to have two SNAP neighbourhoods, as a seventh SNAP is currently in development for the Bramalea area (TRCA, n.d.).

Developed in the 1980s, the area of the County Court SNAP encompasses a golf course, a commercial zone, several suburban residential streets, and a section of the Etobicoke Creek. The SNAP neighbourhood area is home to approximately 5800 people, and most of the dwellings within the area are single detached houses. Several initiatives have been enacted in the SNAP plan for County Court, themed largely around home and landscape retrofitting, community building and consultation, stormwater management interventions, place-making, and natural heritage rehabilitation. Projects range greatly in scale – from public landscape interventions, to retrofits of private dwellings – and each supports effort toward the long-term targets for the County Court Neighbourhood as identified by the SNAP program (see Measurements section) (TRCA, n.d.).

The Bramalea SNAP has not published projects or identified targets yet, but the neighbourhood differs notably from County Court in several ways which may impact the development of its SNAP plan. Firstly, the Bramalea SNAP is home to approximately 13,600 people, and population is more densely distributed in this neighbourhood due to greater diversity of housing types (TRCA, n.d.). Functionally, the Bramalea SNAP area is almost exclusively residential, apart from a few amenities like schools and parks. Further, Bramalea differs architecturally from County Court, and may potentially have significant cultural heritage value relating to its unique history (Svirplys, n.d.).

TIMELINE

| 8000 BCE | Archaeological evidence dates the establishment of hunting camps and small villages along the Credit and Humber river valleys to around 8000 BCE (City of Brampton, 2015, p. 6). | |

| 1818 | Ajetance Treaty, No. 19. signed by Chief Ajetance on behalf of the Mississaugas of the Credit (MCFN, n.d.) | |

| 1820 | First European settlers in Brampton, coming from Brampton, England (City of Brampton, 2015, p. 4). | |

| 1850 | Composite village plan is laid out; Brampton’s first plan of subdivision (City of Brampton, 2015, p. 4). | |

| 1873 | Brampton becomes incorporated as a town (City of Brampton, 2015, p. 4). | |

| 1946 | First of several annexations to accommodate a growing population (City of Brampton, 2015, p. 5). | |

| 1946 | CMHC established. (Canadian Encyclopedia, 2013). | |

| 1948 | Housing Corporation (Ontario) established (Ontario Ministry of Government and Consumer Services, n.d.) | |

| 1948 | The worst flood in the recorded history of Brampton (City of Brampton, 2015, p. 5). | |

| 1950 | Etobicoke River diversion begins in June and is completed in July of 1952 (City of Brampton, 2015, p. 5). | |

| 1957 | TRCA established (City of Toronto, n.d.) | |

| 1958 | Plans for Bramalea satellite city area announced (Svirplys, 2007, p. 2) | |

| 1967 | Home Ownership Made Easy (HOME) program implemented by Housing Corp. which facilitated financing for a large portion of Bramalea (Smith, 1977, p. 22, and Svirplys, n.d.). | |

| 1974 | Brampton incorporated as a City with a population of 88,820 (City of Brampton, 2015, p. 5). | |

| 1980s | Development of County Court area subdivisions (approximate). | |

| 1990s | Build out of Bramalea largely completed (Svirplys, n.d.). | |

| 2009 | TRCA develops SNAP model (TRCA, n.d.) | |

| 2012 | First SNAP projects implementation, including in pilot program in County Court (TRCA, n.d.) | |

| 2014 | Brampton Grow Green Environmental Master Plan Implementation Action Plan (City of Brampton, 2014). | |

| 2018 | Brampton Natural Heritage Restoration Program (City of Brampton, 2018). | |

| 2019 | Bramalea SNAP in development (TRCA, n.d.). |

- Bold: About Brampton History

- Italic: About TRCA

- Bold and Italic: TRCA in Brampton area

STAKEHOLDERS

The SNAP model pursues projects in both public and private sites and engages multiple levels of government to co-ordinate a diverse range of objectives. As such, many stakeholders are key to the successful implementation of SNAP plans, and community engagement described as a SNAP priority.

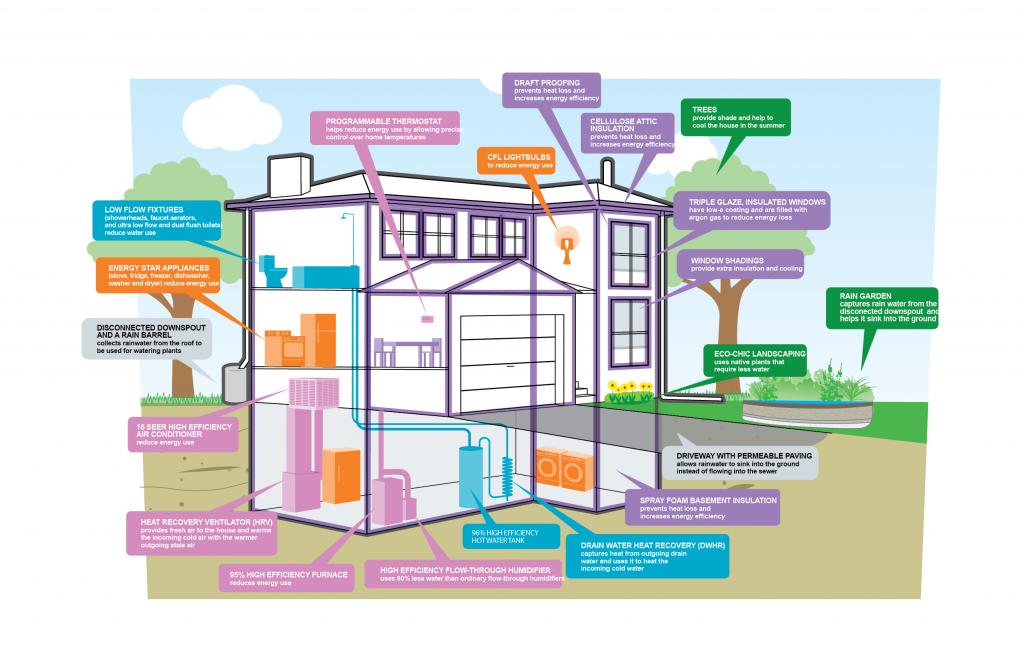

Diagram showing some features of the Green Home Makeover Project, Retrieved from https://trca.ca/conservation/sustainable-neighbourhoods/snap-neighbourhood-projects/county-court-snap/projects-green-home-makeover/

Due to the wide range of SNAP initiatives, even within the County Court neighbourhood exact stakeholders vary from project to project. An example below lists some of the stakeholders involved in the Green Home Makeover project, the objective of which “was to identify the home with the greatest need for upgrading and the greatest potential to demonstrate change.”(TRCA, n.d.) The project sponsored renovations to the selected home, and used the site to showcase what might be achieved through retrofits, and educate other residents on the possibilities for improvement of their home.

- Organizations: the TRCA, the Peel Region, and the City of Brampton facilitated the project. Utilities, like Enbridge and Hydro One Brampton, along with national and provincial organizations like Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, Canada Green Building Council, Ontario Waterworks Association, and Landscape Ontario, are examples of organizations which supported the project as partners.

- Owners/users: Paul Gay and Marisa Mancuso (homeowners), visitors to the home and those who follow the project implantation video series online, other homeowners in the neighbourhood

- Consultants: Energy audit consultant, experts on landscape, HVAC, and water usage, as well as technicians involved in the project implementation. The Sustainable Technologies Evaluation Program (STEP) completed a final report on the performance of the house following the retrofits (STEP, 2014).

Other general stakeholders for SNAP projects not involved in the Green Home Makeover Project include the golf course and other businesses in the SNAP neighbourhood. Additionally, the provincial government of Ontario has been involved in some County Court projects (TRCA, n.d.).

However, even within this broad list of involvement – some key areas of knowledge and expertise may be identified as missing. Throughout the SNAP projects in County Court, no Indigenous communities or organizations have been consulted or involved, nor have any heritage organizations or experts.

HERITAGE

Components of the natural heritage system in Brampton are defined as valleylands, woodlands, wetlands, and lakes. The Etobicoke Creek, along with other smaller creeks and rivers define the landscape of the Brampton area, and provide much of its natural heritage areas. Retrieved from https://www.nakdesignstrategies.com/projects/brampton-natural-heritage-system/

Natural Heritage in Brampton: As per the mandates and vision of the TRCA, emphasis of the SNAP program focuses more toward natural heritage and the health of water systems (TRCA, n.d.). Brampton, as a municipality, recognizes the value of natural heritage, and demonstrates that its conservation is a priority through its publications including Brampton’s Grow Green Environmental Plan (City of Brampton, 2014), and the city’s plan for the Natural Heritage Restoration Program (City of Brampton, 2018). In the latter document valleylands, woodlands, wetlands, and lakes are identified as components in Brampton’s natural heritage systems. In response to heavy development and disruption of the natural environment since the 1970s, the City of Brampton states that it aims not only for the preservation of remaining natural heritage, but to further the “restoration, enhancement and expansion of the remaining natural features and functions” (City of Brampton, 2018).

Heritage building in Brampton, typical of older structures which have often been given preference in the selection of built heritage in Brampton. Retrieved from https://www.realtor.ca/blog/postpage/8051/1365/discover-the-stunning-historical-mansions-of-brampton-ontario

Built Heritage in Brampton: Built heritage in Brampton has typically focused on buildings from the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth century. The 2009 Heritage Conservation Districts Feasibility Study indicates interest in buildings constructed pre-1946 (George Robb Architect et al. 2009), and the two heritage conservation districts which have been designated in Brampton represent early European settlement. These existing designated districts are Churchville and Main Street South (see maps in Description section). However, recent trends may indicate that Brampton has increasing interest in modern heritage.

Historic image of the Bramalea neighbourhood from 1969. From the Toronto Public Library Archives, “Ontario Housing Corporation under its Home Ownership Made Easy plan made it possible for potential homeowners to buy many of these houses on Edenridge Dr. in Bramalea for $15,000 plus the price of the lot.” Retrieved from https://www.torontopubliclibrary.ca/search.jsp;jsessionid=Wv-UHqQs7u1tghblm6bzoUdj.tplapp-p-1b?Ntt=Bramalea+(Ont.)&Ntk=Subject_Search_Interface&view=grid&Erp=20

Study Plan of Bramalea development from 1958 when the project was announced. Retrieved from https://trca.ca/conservation/sustainable-neighbourhoods/snap-neighbourhood-projects/bramalea-snap/

The areas included within the County Court and Bramalea SNAPs are not currently identified as having significant built heritage. County Court is typical of 1980s suburban residential development. While there is no official heritage recognition for Bramalea as a district or neighbourhood, just outside of the SNAP zone in the wider Bramalea neighbourhood, a few non-residential structures have received municipal heritage listing (City of Brampton, n.d.). This includes the Former Bacardi Plant, which was showcased in the 2019 edition of the annual newsletter, the Brampton Heritage Times; this feature article is a first for any site within Bramalea (Brampton Heritage Board and City of Brampton, 2019).

There are precedents elsewhere of municipalities protecting postwar suburbs as Heritage Conservation Districts – for example, Briarcliffe in Ottawa (City of Ottawa, 2012). Structures in the early areas of Bramalea are representative of mid-century modern suburban homes, and as the first satellite city, the community undoubtedly impacted the design and implementation of other suburban developments across the country. With historical significance which extends beyond Brampton and reflects a milestone in urban development in Canada – Bramalea has tremendous cultural heritage potential. It would likely benefit the development of the Bramalea SNAP plan to include the Brampton Heritage Board, or other cultural heritage organizations or experts among its stakeholders.

Natural and Cultural Heritage: Broader recognition of heritage types and heritage potential might serve to further the multi-objective approach already embedded in the SNAP model and support the pursuit of even more holistic sustainability in Brampton. David Harmon argues that “better conservation outcomes might well be produced if (natural and cultural heritage conservation) could work together by focusing on common points of agreement” (Harmon, 2007, p. 380). In their research on Protected Areas in the United States, Oldekorp et al identified a correlation that “protected areas associated with positive socioeconomic outcomes were more likely to report positive conservation outcomes,” which suggests that the integration of social and environmental objectives may be mutually beneficial (Oldekorp et al, 2015, 133). The Bramalea SNAP has the potential to offer new opportunities for integrating both cultural and natural heritage conservation.

SUSTAINABILITY

Environmental and Social Sustainability in County Court SNAP: The basis for the SNAP program stems from the TRCA’s work to further environmental stewardship of the GTA’s watersheds in a heavily urbanized context. Because of this, the work in the County Court SNAP has strongly integrated both environmental and social types of sustainability. However, this emphasis may suggest that improved inclusion of cultural and economic sustainability objectives may offer opportunities to further the SNAP scope, and to better serve local communities.

Aerial view of the County Court SNAP. Rehabilitation of the landscape, and natural heritage systems surrounding the Etobicoke Creek form a major component of the work in County Court, and relates to the watershed-driven objectives of the TRCA. Retrieved from: https://trca.ca/conservation/sustainable-neighbourhoods/snap-neighbourhood-projects/county-court-snap/

Projects in the County Court SNAP include (TRCA, n.d.):

- Renewal of County Court Park to better suit local recreation needs and integrate environmental education features and community gathering space.

- Retrofit of the Upper Nine stormwater management pond to address water quality and volume objectives and serve as a community amenity and natural area destination.

- Projects for greener streetscapes including bioretention within boulevards to provide stormwater filtration and other benefits, as well as establishment of a healthy urban forest.

- A rainwater storage system for irrigation of nearby golf courses.

- Habitat restoration along the Creek valley and in the golf courses.

- A template for green parking lot design at the Court House.

- Active promotion of green home renovation and landscapes to address residential energy and water conservation.

This series of projects suggest different relationships which might be understood to exist between environmental and social objectives.

- The first three projects describe both environmental and social benefits; these initiatives involve improvements to outdoor public spaces which positively impact user experience and provide learning experiences whilst addressing natural systems and supporting local ecologies. These projects suggest that social and environmental objectives can at times be aligned.

- In projects 4, 5, and 6 the emphasis is more overtly environmental – human intervention is highlighted as problematic to Brampton’s natural systems. The seventh project looks at homes as areas of opportunity to lessen the environmental impact that families and individuals have on the communities where they live. In each project, the function remains continuous; these examples demonstrate how patterns of development might be rehabilitated to continue meeting social needs, while better addressing environmental objectives.

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Beyond the Pillars of Sustainability (often considered to be environmental, social, economic, and sometimes cultural) the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) offer another avenue for understanding holistic sustainable development. Three SDGs which pertain strongly to the SNAP program are Goal 6: Clean Water and Sanitation, Goal 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities, and Goal 15: Life on Land (UN, 2019). Targets from each of these goals have been selected and paraphrased below to highlight how the projects of the County Court SNAP may align with SDG objectives:

Goal 6: Clean Water and Sanitation Targets include:

- (6.4): increase water-use efficiency

- (6.5): implement integrated water resource management

- (6.6): protect and restore water-related ecosystems

- (6.B): supporting and strengthening the participation of local communities in improving water and sanitation management

Most County Court projects involve stormwater management and landscaping designed to improve the health of the Etobicoke river, its watershed, and the habitat it provides to local wildlife. Rainwater and irrigation objectives address water-use reduction.

Goal 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities Targets include:

- (11.4): safeguarding cultural and natural heritage

- (11.6): reducing the adverse environmental impact of cities

- (11.7): providing universal access to safe, inclusive, accessible, green and public spaces

- (11A): strengthening national and regional development planning

- (11B): and implementing integrated policies and plans

Goal 15: Life on Land Targets include:

- (15.1): Ensuring the conservation, restoration and sustainable use of terrestrial and inland freshwater ecosystems

- (15.A): integrating ecosystem and biodiversity values into national and local planning; and, mobilizing resources to conserve and sustainably use biodiversity and ecosystems

With respect to Goals 6 and 15, most County Court projects involve stormwater management and landscaping designed to improve the health of the Etobicoke river, its watershed, and the habitat it provides to local wildlife. Rainwater and irrigation objectives address water-use reduction.

In light of Goal 11, County Court SNAP projects strongly address natural heritage, but do not integrate cultural heritage considerations – this is identified as a potential area for improvement in the development of the Bramalea SNAP. “Reducing the adverse environmental impact of cities” is an idea central to the SNAP model, and improvement of public green spaces simultaneously furthers social and environmental objectives of Sustainable Cities and Communities (UN, 2019).

MEASUREMENT

A study of the County Court SNAP yields a positive example in localizing regional objectives and integrating multiple sustainability objectives within community-specific projects. However, a study of the application of this integrated approach may identify gaps, or areas showing room for improvement in pursuit of a truly holistic sustainability. The first section below contains indicators of how the County Court SNAP might be assessed in how it is measuring up to its intended results. The second section below uses some of the gaps recognized in the analysis of the County Court SNAP to project some future objectives for the development and implementation of the Bramalea SNAP.

County Court SNAP Indications of Success Based on its Intended Outcomes: The SNAP plan identifies a series of long-term targets for the County Court Neighbourhood. These pertain to extending urban forest cover, improving stormwater management, reduce the use of resources like energy and water, specific carbon targets, and levels of support for terrestrial natural heritage systems. Progress toward these goals can help to measure the effects of implemented projects.

These objectives are (TRCA, n.d.):

• Expand urban forest cover to 18.4% community, 40.4%

overall

• Improve stormwater quantity & quality, erosion control, water balance

• Reduce water use to 144 Lcd (31%) residential, 46% commercial

• Reduce energy use by 39% residential, 53% commercial

• Reduce GHG by 18% (6300t CO2e) compared to 2009 baseline (energy and water)

• Ecoservices (snapshot at 2061)

• UF – annual 570t carbon storage ($13K), 214t carbon sequestration ($5K),

pollution removal 11t ($100K)

• TNHS – increase from $450K to $1.5M value

Beyond these, from general analysis, level of success toward the intended goals of the SNAP project may be assessed by:

- The number of projects implemented, and the range of sustainability objectives addressed by projects.

- Indications of level of community engagement and participation may reflect how well the localization of the program is enacted on the ground.

- The introduction of a second SNAP within Brampton suggests that the system has been generally well received by the city and the community, if they are willing to develop another.

County Court SNAP Indications of Success Based on External Metrics:

Environmental Sustainability of the Built Environment: LEED for Neighbourhood Development (LEED ND) may be a useful tool in assessing the sustainability of the built environment, largely from an environmental perspective. The credit-based system is similar to the popular LEED system for the evaluation of the design of individual buildings; however, the this program looks at the scale of a community, and awards points within categories of Green Infrastructure and Buildings, Neighbourhood Pattern and Design, Smart Location and Linkage, as well as Innovation and Design Process. Within the system, criteria described as ‘Prerequisite’ are required, while those listed as ‘Credit’ are optional. Though typically used for the construction of new neighbourhoods, or applied at the site of a major residential/mixed use intervention to an existing site – some of the criteria are useful to look at to get a sense of some of the building blocks which might support the making of a sustainable community.

LEED ND criteria that might be useful in evaluating the impact of the County Court SNAP include:

| Criteria | County Court SNAP application | |

| Wetland and Water Body Conservation and Restoration | Projects have included habitat rehabilitation, and stormwater management | |

| Reduced Parking Footprint | Projects include template for green parking lot design at the Court House | |

| Walkable Streets Tree-lined and shaded streets | Projects for greener streetscapes including bioretention and “establishment of a healthy urban forest” (TRCA, n.d.) | |

| Community Outreach and Involvement | One project included “A neighbourhood-scale vulnerability assessment and adaption initiative co-created by residents and stakeholders to prepare for extreme weather emergencies and inform final SNAP Action Plan implementation” (TRCA, n.d.) | |

| Access to Recreation Facilities | Renewal of County Court Park to better suit local recreation needs and integrate environmental education features and community gathering space. | |

| Building Energy Efficiency Building Water Efficiency | The Green Home Makeover projects address building performance, including water and energy efficiency | |

| Water-efficient Landscaping Stormwater management | Projected implemented to use stormwater to irrigate the golf course within the site. Bioretention and filtering of stormwater also addresses these criteria |

There are many more criteria in LEED ND that would need to be addressed before the County Court neighbourhood could be classified as a LEED rated neighbourhood. However, all of the projects implemented within this SNAP address and makes positive progress toward some criteria or another. So while this may not be a comprehensive way to assess built sustainability – it is strongly indicative of improvements toward improved sustainability of a neighbourhood.

Social Sustainability of the Community: In a 2007 article for the International Journal of Heritage Studies, Chris Landorf puts forward a framework of criteria for evaluation social sustainability, within existing communities. These were developed with the idea in mind that because of their more qualitative nature, social sustainability are often not prioritized in the same way that economic or environmental objectives are. This framework is divided in to three top categories of Social Equity, Social Coherence, and Basic Needs. Some of these criteria may be useful for assessing the social impact of the County Court SNAP projects. These criteria point toward the beginnings of some social sustainability – but further suggests that there may be room for improvement, to involve more social programming and facilitation in the projects of the SNAP program.

Social Equity

- is addressed only in Social Infrastructure, which includes cultural events, historic resources and recreation facilities. Improvement to greenspace supports recreation

- The other two criteria of Housing Infrastructure quantity and diversity, Community infrastructure (services) may offer opportunities to expand the scope of the SNAPs effects to social equity.

Social coherence

- in the subcategory of Strength of networks, Participation, Identification may all be addressed in the projects, through community engagement, involvement, and creation of stronger community places

Basic Needs

- Most criteria in the category of basic needs are not addressed, Built Environment quality is strongly addressed through interventions to landscape and buildings

Potential future indicators for the Bramalea SNAP as furthering the SNAP model: Beyond the present performance of the County Court SNAP toward its intended outcomes, a study including the future Bramalea SNAP suggests some areas where there might be room to expand the SNAP scope to better address a wider range of objectives. Indicators of growth or evolution of the program to better address the realities and the needs of the Bramalea site might include:

- Consultation/involvement of Indigenous communities or organizations

- Consultation/involvement of heritage organizations or experts

- Integration of natural and cultural heritage conservation objectives and projects

- Recognition of Bramalea as an historic neighbourhood, and projects which further public knowledge of the history of the area

- Goals/targets/projects which better address/incorporate cultural and economic sustainabilities

- Building rehabilitation projects which consider the potential heritage value of Bramalea buildings

REFERENCES

Books, Journal Articles, Theses, Newsletters

- Brampton Heritage Board and City of Brampton. (2019). The Brampton Heritage Times. Retrieved from https://www.brampton.ca/EN/Arts-Culture-Tourism/Cultural-Heritage/Documents1/Heritage_Times_Newsletter_2019.pdf

- Harmon, David. (2007). “A Bridge over the Chasm: Finding Ways to Achieve Integrated Natural and Cultural Heritage Conservation.” International Journal of Heritage Studies, 13. 4–5: 380–392.

- Landorf, Chris. (2011). “Evaluating social sustainability in historic urban environments.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 17.5, 463-477.

- Oldekorp,J.A. et al. (2015). “A global assessment of the social and conservation outcomes of protected areas.” Conservation Biology 30.1, 133-141.

- Smith, Lawrence B. (1977). Anatomy of a Crisis: Canadian Housing Policy in The Seventies. Vancouver, BC: Fraser Institute.

- Svirplys, Saulius. (2007). “Creeping diversity”: Housing design in Bramalea, Canada’s first suburban satellite city. (Masters thesis). University of Ottawa, Ottawa. Retrieved from: https://ruor.uottawa.ca/bitstream/10393/27488/1/MR32481.PDF

Policies and Reports

- City of Brampton. (2014). Brampton Grow Green Environmental Master Plan: Implementation Action Plan. Retrieved from https://www.brampton.ca/EN/Business/planning-development/projects-studies/Documents/Environmental%20Master%20Plan/Final%20Documents/Brampton%20IAP_11_10_2014.pdf

- City of Brampton. (2015). A Walk Through Time Downtown Heritage Walking Tour. Retrieved from https://www.brampton.ca/EN/Arts-Culture-Tourism/Cultural-Heritage/Documents1/Downtown_Heritage_Walking_Tour.pdf

- City of Brampton. (2018). Natural Heritage Restoration Program. Retrieved from https://www.brampton.ca/EN/residents/GrowGreen/Documents/NHRP_Final_April_2018.pdf

- City of Ottawa. (2012). Briarcliffe Heritage Conservation District Study and Plan. Retrieved from http://www.capitalmodern.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/FINAL-Briarcliffe-HCD-Study-Plan.pdf

- George Robb Architect et al. (2009). HERITAGE CONSERVATION DISTRICT FEASIBILITY STUDY: for the Establishment of Heritage Conservation Districts in Downtown Brampton. Retrieved from https://www.brampton.ca/EN/Arts-Culture-Tourism/Cultural-Heritage/Documents1/Downtown_HCD_Feasibility_Study_2009.pdf

- CGBC. (2009) LEED for Neighbourhood Development with Canadian Compliance Paths. Retrieved from https://www.cagbc.org/CAGBC/Programs/LEED/LEED_Canada_Rating_System/Neighbourhood_Development.aspx

- Sustainable Technologies Evaluation Program (STEP). (2014). Sustainable Neighbourhood Retrofit Action Plan (SNAP) County Court – 71 Turtlecreek Blvd. Green Home Makeover Energy and Water Use and Stormwater Monitoring Final Report. Retrieved from https://s3-ca-central-1.amazonaws.com/trcaca/app/uploads/2016/09/17180152/GHM_Final-Monitoring-Report_FINAL_20150203.pdf

- United Nations (UN). (2019). About the Sustainable Development Goals. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

Websites

- City of Brampton. (n.d.) Planning Viewer. Retrieved from http://maps1.brampton.ca/PlanningViewer/

- City of Toronto. (n.d.). Toronto & Region Conservation Authority. Retrieved from https://www.toronto.ca/city-government/accountability-operations-customer-service/city-administration/city-managers-office/agencies-corporations/agencies/toronto-and-region-conservation-authority/

- The Canadian Encyclopedia. (2013). Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/canada-mortgage-and-housing-corporation

- Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation (MCFN). (n. d.). Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation. Retrieved from http://mncfn.ca/

- Ontario Ministry of Government and Consumer Services. (n.d.). Archives of Ontario, Housing Corportion (Ont.). Retrieved from http://ao.minisisinc.com/scripts/mwimain.dll/144/ARCH_AUTHORITY/AUTH_DESC_DET_REP/SISN%208424?SESSIONSEARCH

- Svirplys, Saul. (n.d.). Bramaleablog. Retrieved from https://bramaleablog.wordpress.com/about/

- Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA). (n.d.). Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA). Retrieved from https://trca.ca/about/

Sources of images indicated above with captions. Feature Image: Suburban residential development abutting the Natural Heritage System of the Brampton area. Retrieved from https://www.nakdesignstrategies.com/projects/brampton-natural-heritage-system/