The Canadian Heritage Rivers System and the Grand River Watershed, Ontario

Case Study prepared by David Siebert, SICS, Carleton University

Keywords: Canadian Heritage Rivers System, Grand River, conservation authority, watershed.

LESSONS LEARNED

The primary lessons from this case study are:

- A watershed approach to designation is beneficial for both the managing body – in this case the Grand River Conservation Authority (GRCA) – as well as the river itself;

- Breaking down the divide between nature and culture is beneficial to understand human relationships with rivers;

- Designation can be overly restrictive, distracting from the “complex ‘whole’” (Leitão, 2017, p. 207);

- Approaching both the designation and the watershed from a hydrosocial perspective benefits the health and culture of and within the watershed.

Designating the entire Grand River watershed as a Canadian Heritage Rivers System (CHRS) has benefitted the Grand River Conservation Authority (GRCA) and the designated area. This has allowed for cross-jurisdictional approaches to heritage and tourism, as well as incorporating conservation into more than a ‘nature or culture’ discussion. The conservation of the watershed benefits from fuller discussions of what conservation means, and a deeper understanding of how interconnected the CHRS’ values of nature, culture and recreation are.

For the GRCA the designation has allowed for a new relationship with the river beyond its historic purview over flood management and water quality. For the heritage designation, the GRCA’s watershed level scope has allowed for better opportunities for place-making and identity creation. A 2010 Gaps Analysis of the CHRS forwarded several important next steps, but did not make recommendations towards what scale to designate. The lesson it derived from the Grand River was that it provided an example of a “working river” (2010, p. 5). The lesson is a scale larger than that: that the Grand River provides an example of conservation that cross the nature/culture dichotomy.

The incorporation of the heritage designation has created the beginnings of a hydrosocial understanding of the Grand River. Linton and Budds define the hydrosocial cycle as how our understanding of water transcends boundaries of physical and social, and can consider interrelations, such as political, cultural, and economic dimensions that hydrologic water management does not (2014, p. 173, 175). This new relationship has great potential and positions the GRCA to take a leadership role in the heritage and cultural conservation of the Grand River.

PRESENTATION

DESCRIPTION

Canadian Heritage Rivers System: The Canadian Heritage Rivers System (CHRS) was created in 1984 as a voluntary, non-legislated, designation system to recognize rivers of “outstanding Canadian value.” Each designated river must recognize at least one of the three values of the CHRS: natural heritage, cultural heritage, and/or recreational value (Doyle & Noel, 1995, p. 187). The goals of the designations are to increase national and international interest in the rivers, advocate for local stewardship, and “express our nation’s history, our beautiful landscapes, and our way of living” (CHRS, 2008, p. 3).

The CHRS was created prior to the adoption of cultural landscapes at the 1992 World Heritage Committee, and as such marks a very early attempt on the part of Parks Canada to find a way to designate landscape for more than just natural or cultural values. The early designations, such as the French River, show how the CHRS was intended to transmit a certain narrative about Canada and the settlement of Canada. This has not gone without criticism, especially as these designations bought into outdated stories about the origins of settler Canada (Erickson, 2015, p. 321).

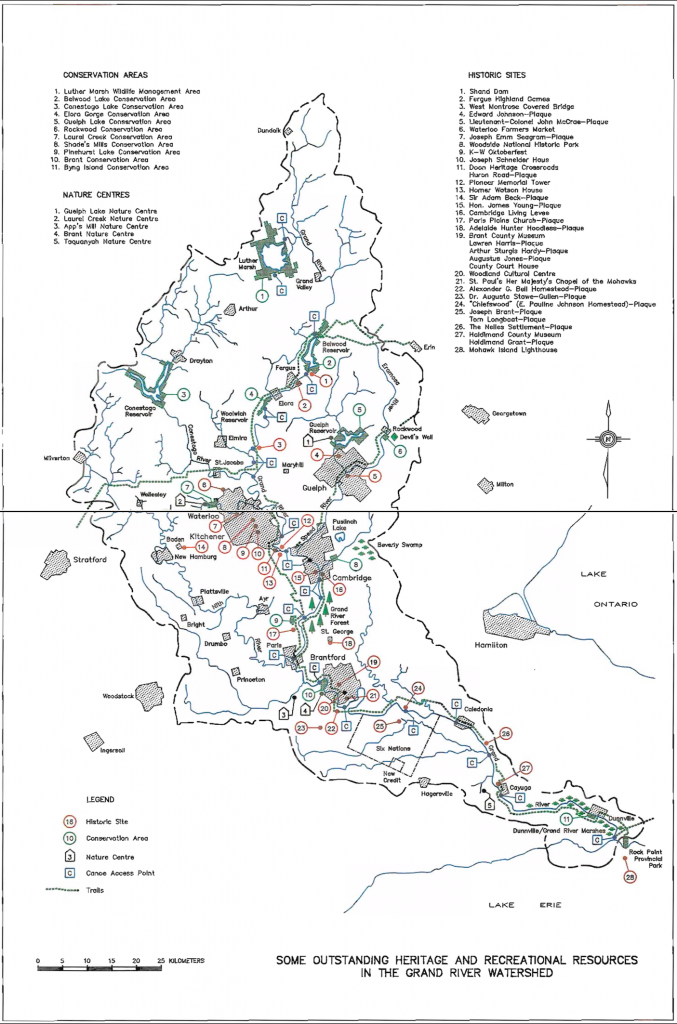

The Grand River: The Grand River runs 290 km from its headwaters around Dundalk to its mouth at Port Maitland. The Grand’s watershed covers approximately 6,800 km2 of southern Ontario and is part of the Lake Erie watershed. The population of the watershed is close to one million, and expected to rise (Our watershed, n.d., n.p.). The Grand River Conservation Authority (GRCA) is responsible for watershed level water management, numerous recreation areas, and is the managing body responsible for the Grand River’s heritage system designation. They are a vitally important piece of the CHRS designation and will be discussed further below.

The Grand River was in designated 1994, marking a shift in the CHRS away from designating ‘wild’ rivers already within National or Provincial Parks to designating populated rivers outside already protected areas (CHRS, 2010, pg 5). The Grand River is a unique designation, as the designation area covers not only the Grand River itself, but also the four major tributaries: the Conestogo, Eramosa, Nith, and Speed Rivers. The Grand Strategy, the foundational managing document created for the designation process, states that “the area to be designated and managed as a Canadian Heritage River will include the entire Grand River watershed” (GRCA, 1994, p. 5).

Under the CHRS the Grand River is designated for its cultural and recreational values, not its natural heritage values. This is likely because the Grand is not a free-flowing river, and has been dammed and managed in various ways, both harmful and helpful, since early European settlement (A tale of two dams, 2009, 13). These dams, thought, constitute part of the cultural heritage designation.

TIMELINE

- 20,000 – 11,000 years ago glacier retreat, heavily influencing geography and geology of watershed (The Grand, 2009, p. 3).

- 10,000 years ago – earliest material evidence of Indigenous people living in the watershed (The Grand, 2009, p. 3).

- Pre-contact – Grand River watershed used by Anishinaabe.

- 1784 – Haldimand Proclamation gives Six Nations of the Grand River 10 km on either side of the Grand River; Mississauga of the New Credit grand land to Six Nations of the Grand River through the Colonial government (Filice, 2016, n.p.). The majority of the population of the Grand River watershed lives with this 10km stretch.

- 1820s-1850s – Early settlement of watershed by white settlers through Block sales by Joseph Brant or illegal squatting.

- 1829 – Dunnville Dam built to supply water to the Welland Canal via a feeder canal (The Grand, 2009, p.13).

- 1832 – Grand River Navigation Company. Financed unknowingly by the Six Nations of the Grand River (Six Nations, 2015 p.14).

- 1934 – Grand River Conservation Commission established by Brantford, Kitchener, Galt, Fergus, and Caledonia.

- 1942 – Conservation Commission completes construction of Shand Dam, first multi-function dam in Canada (built for water quality, flow, and supply). (See Fig. 4).

- 1948 – Grand Valley Conservation Authority created under Conservation Authorities Act of 1946. Conservation Authority creates parks and recreation areas.

- 1966 – Grand River Conservation Commission and Grand Valley Conservation Authority merge due to overlapping interests. New agency called the Grand River Conservation Authority.

- 1974 – Major flooding. Resulted in Royal Commission Inquiry into Grand River Flood (GRCA, History, n.p.).

- 1986 – Canada Heritage Rivers System established.

- 1992 – Cultural landscapes adopted and defined by World Heritage Committee.

- 1994 – September 25th, Grand River officially designated Canadian Heritage Rivers System. The ceremony in Cambridge was attended by 750 people (Noel, 1995, p. 123), (GRCA, 2014, p. 44).

- 2000 – Grand River Conservation Authority wins Thiess International Riverprize.

- 2009 – Grand River Fisheries Management Plan Implementation Committee received Recreational Fisheries Award from Minister for Fisheries and Oceans.

- 2019 – Provincial government reduces funding to conservation authorities and orders them to “wind down” programs not essential to their core programming (Syed, 2019, np). It is not clear what is deemed non-essential, or how this will impact conservation work.

STAKEHOLDERS

- Federal Government

- Parks Canada

- Canadian Heritage Rivers Board

- Parks Canada

- Indigenous Rights-holders

- Six Nations of the Grand River

- Mississauga of the New Credit

- Provincial Government

- Conservation legislation

- Grand River Conservation Authority (GRCA)

- Required to sign on to nomination of potential heritage rivers

- Conservation legislation

- Municipal Governments

- Counties & Regions

- Citizens and politicians sit on the GRCA board of directors

- The GRCA consulted with 200+ organizations and individuals in the creation of The Grand Strategy

- Counties & Regions

- Conservation organizations

- E.g. Historical societies

- Special interest groups

- E.g. Tourism businesses, universities, commercial businesses

I have chose to use the term “Rights-holders” to describe the Indigenous peoples living within the Grand River watershed. This distinction is important as the Indigenous peoples are more than stakeholders – they carry rights recognized and unrecognized by the various levels of Government associated with the designation. Their interest in the Grand River is more than, say, a cultural or commercial partner.

The relationship between the GRCA and Parks Canada is important to understanding the heritage river designation. The GRCA is an old water management conservation authority (provincially legislated by the 1946 Conservation Authorities Act) (“GRCA history”, n.d. n.p.). In 1987 the GRCA began the nomination process to make the Grand River a heritage river, and after designation in 1994 the GRCA became the managing body of the Grand River (Noel, 1995, pg 123).

As the managing body they are responsible to the Canadian Heritage Rivers Board for the CHRS designation and have incorporated the CHRS designation into their own identity, including strategic planning (Strategic Plan 2019-2021, 2019, pg 8). They report to Parks Canada through the Canadian Heritage Rivers Board in annual reports, and ten-year monitoring reports conceived of, by the GRCA, as extensions of the 1994 Grand Strategy (Veale, 2004, p. X).

HERITAGE

Natural-cultural heritage: Of the three values held by the CHRS, the Grand River’s designation covers only cultural and recreation, not natural heritage. The Grand Strategy lists five features associated with cultural heritage, and five associated with natural heritage, (see below). In the ten-year monitoring reports (2004 & 2014) natural heritage is still reported in full in the 2014 report (GRCA, 2014, 21).

Five themes representing the cultural heritage (referred to as “human heritage” in The Grand Strategy):

- “The watershed’s cultural mosaic since the mid-nineteenth century;

- The strong association of the Native Peoples with the watershed for thousands of years;

- The Grand River’s industrial heritage;

- Human adaptation of fluctuating river flows; and,

- The many famous persons associated with the Grand River watershed” (GRCA, 1994, p. 3).

The GRCA does not own or directly manage any of the built heritage it lists in subsequent monitoring reports, and so features like bridges and historic industrial mills became of interest to the conservation authority for their cultural values, not just their impact on water flow, after the CHRS designation. Through the heritage river designation, they have a vested interest in the cultural heritage of the watershed, and increasingly interdisciplinary in their planning (GRCA, 2004, p. 4). The built heritage that the designation mentions directly or indirectly (through images) is predominantly the industrial heritage of Wellington and Waterloo Counties, while the intangible heritage is either rural (the “cultural mosaic”) or Indigenous (GRCA, 1994, p. 3).

Five themes representing the recreational values:

- “Water sports;

- nature/scenic appreciation;

- Fishing and hunting;

- Trails and corridors; and,

- Human heritage appreciation” (GRCA, 1994, p. 3).

The emphasis on recreational use is part of the early vision of the CHRS, and for the Grand River plays a role in both place-making and economic development. The GRCA manages 12 parks in the watershed, and already had an interest in the recreation use of the Grand River prior to designation. The heritage designation does allow the GRCA to incorporate recreational values into larger discussions about environmental protection. Fishing and angling, for instance, corresponds with both recreational use and the environmental health of the river. This interrelation between nature and culture emerges in the origin of the Grand River’s designation in 1994 (GRCA, 1994, p. 21). Although the designation occurred prior to the articulation of cultural landscapes, the GRCA still was able to incorporate some of the values of a cultural landscape approach into the heritage river designation.

The Grand Strategy outlines natural heritage of the river includes predominantly geological features (Elora gorge, Devil’s Well pothole, moraines and aquifers), wildlife associated with areas of the river (especially Luther Marsh), and the last remnants of disappearing ecosystems (i.e. Carolinian forest) (GRCA, 1994, p. 38). Because the GRCA’s mandate is environmental management, the natural heritage of the river remains a concern whether or not it is part of the heritage designation. In The Grand Strategy the GRCA outlined two central goals that remain unchanged in the 2014 ten-year report:

- “To strengthen, through shared responsibility, the knowledge, stewardship and enjoyment of heritage and recreation resources of the Grand River watershed.

- To improve the well-being of all life in the Grand River watershed” (2014, p. 53).

From these goals the GRCA incorporates all three values into its interests (nature sneakily included the “well-being of all life”). The relationship between the GRCA’s responsibilities as conservation authority and managers of the heritage designation means that drawing a line between what is natural heritage versus cultural heritage can be very difficult and at times counterproductive to our understanding of designation. Delineating the cultural/natural/recreational values serves to disguise some of the interrelationships between theme areas. In the CHRS integrity guidelines, aesthetic values, for example, are discussed as part of natural, cultural and recreational integrity (CHRS, 2017, p. 51-52).

SUSTAINABILITY

With the Grand River heritage designation incorporated into the GRCA is involved, in some capacity, in a greater range of sustainable actions than before the designation. The mandate of the GRCA largely covers environmental sustainability, especially through wildlife regeneration, and water quality concerns around sewage and farm runoff. The rivers mentioned in the heritage designation have all grown healthier since the creation of the GRCA, although the bar for some was very low due to industrial effluent (Thompson, 2017, n.p.).

Environmental sustainability: Even without designated natural heritage values the CHRS designation still pertains to a river. Other parts of the designation cover environmental sustainability. In addition, one of the central goals of the designation is to “improve the well-being of all life” (emphasis added), which circumvents the lack of natural heritage designation. It also demonstrates that in 1994 the GRCA was working towards connecting the heritage designation into their larger goals as a conservation authority.

The 2014 ten-year report lists (among other features) fishing, water extraction, and environmental regulation (including flood control and Environmental Impact assessments) all as cultural values supporting the heritage designation (GRCA, 2014, p. 35-38). These intersect with environmental sustainability as they pertain to the ongoing health of the river, the level and impact of habitation and industry, and concerns around water management. There is an entire section under recreation values for angling and hunting, which lists concerns about climate change in respect to ice fishing, the decommissioning of dams helping access to fish spawning grounds, and outdoor education through various bodies including the GRCA.

Social and cultural sustainability: One of the goals of the designation was to increase the profile of the Grand River in the minds of its inhabitants. Barbara Veale, co-chair of the GRCA during the nomination period, said in a 2014 interview “before the designation, we turned our back (sic) on the river” but since the designation the watershed has increasingly embraced the river as part of their identity (Baine, 2014, p. 4). The designation has brought identity and sense of place to the watershed.

The GRCA has also increased their interest in heritage as part of the designation. They have a stake in supporting built and cultural heritage initiatives pertaining to the Grand River. The Grand Strategy outlines this interest, and decadal reports monitor and report changes to the cultural heritage along the river. In 1995 the GRCA created the Heritage Working Group to monitor changes in cultural heritage associated with CHRS designation and run an annual Heritage Day Workshop to discuss management issues and increase awareness of the Grand’s heritage status (GRCA 2004 p. 29).

Economic sustainability: The choice to use ‘recreation’ as a value, and the subsequent theme groups under that value have served to embed tourism as a function, pursuit, and purpose of designating heritage rivers. The aesthetic and natural integrity of designated rivers is important because they are intended for recreational use. In 1996 Grand River Country Tourism Alliance, developed joint tourism advertising, and publications drawing from the CHRS designation. Their website is no longer operational, but their publications are available through the GRCA website. The 2014 decadal report mentions increases in tourism, including visitors coming from outside the watershed attracted by the heritage designation, but the report does not provide visitor numbers or a direct monetary benefit of these tourists.

Increased awareness and interest in the Grand, as well as progressively cleaner water, has also resulted in the adaptive reuse of heritage buildings along the river. Many of these are for commercial/residential use. Historic mill towns like Elora, Fergus, and Galt all use the Grand as part of their heritage tourism appeal (GRCA, 2014, p. 36).

Interconnections: Given the GRCA’s mandate primarily covers flood control and water quality, these intersect with the heritage designation resulting in a new relationship between river and river manager. This relationship contributes to the livability and viability of the Grand River by not only keeping water quality high for drinking, but allowing other activities to take place, and allow for the well-being of all life throughout the watershed. Social sustainability through built heritage and riparian cultural activities add to the continued support for these practices to continue. The GRCA’s continued

MEASUREMENT

Conservation Authority principles: The Grand River Conservation Authority’s 1994 Grand Strategy outlines both the ‘Purpose’ (p. 7) and ‘Opportunities’ (p. 21) that designation would afford them. They display forward thinking in terms of integrating conservation of natural and cultural heritage. The most significant of these are the ‘Purpose’ of “embody[ing] long-term commitments to the identification, protection, interpretation and sustainable use of the river’s nationally recognized heritage”, and the most significant ‘Opportunity’ presented is to “emphasiz[e] the interrelationships between natural and human heritage.”

Principles for bridging natural and cultural heritage: Using Leitão’s insights into World Heritage we can observe that the Grand River’s heritage designation is succeeding at several points. Leitão discusses and analyses how and why the barriers between nature and culture should be broken down at a World Heritage level, and critically discusses how Outstanding Universal Value disguises many values a site has at a local level. Leitão emphasises that values assessments should emphasize the interrelations between values, that recognizing interrelations can make better management practices, and that mono-disciplinary agencies cannot.

Conservation management strategies: By adopting the CHRS designation as part of its identity the GRCA has integrated heritage approaches to its conservation management, resulting in an interdisciplinary approach. Two programs that two on that are the Grand River Fisheries Management Plan (1998) that responded to the increased interest around the heritage designation and increasingly healthy river by creating a community-based, watershed level management plan (Wright & Imhof, 2001, p. 1). The other are two Heritage Bridge Inventories, which would normally fall outside the GRCA’s mandate. However, due to the cultural heritage interest of the GRCA post-designation, the conservation authority has increasingly made cultural heritage part of its advocacy and interests. The two bridge inventories are a direct result of the CHRS heritage designation (Benjamin, 2013, p. 4).

Rights of Indigenous Peoples: The Grand River’s monitoring reports do not explicitly indicate involvement with Indigenous rights-holders. In the 2024 monitoring report it would be welcome to see how recent developments, like the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) are being implemented. UNDRIP mentions rights that overlap with both the work of the GRCA and the CHRS designation (see Articles 29 and 31 in particular).

Sustainable Development Goals: Many of the United Nations SDGs apply to the work of the GRCA, so only one has been chosen here to represent what the heritage river designation adds, with minimal overlap between other work the GRCA performs:

“11.A Support positive economic, social and environmental links between urban, peri-urban and rural areas by strengthening national and regional development planning” (UN, n.d. n.p.)

11.A is supported by the heritage designation because it adds to the scope and depth of planning related interests the GRCA performs. It emphasizes the watershed scale approach the GRCA took in designating the Grand River, as well as demonstrating the holistic approach the heritage designation gives to the GRCA. Planning for the nature-culture and recreation of the Grand River is a cross-jurisdictional and multi-stakeholder/rights-holder affair. It emphasizes the three pillars of sustainability through regional level planning.

This regional planning has also benefitted people across the watershed, and one of the successes of the designation is how much the Grand has been adopted by the people living in the watershed. As discussed in Sustainability, the Grand River has become an integrated part of the relationship between people, place, river, and self.

REFERENCES

Books/Book chapters/Journal articles

- n.a. (2009). A Tale of Two Dams. The Grand, p. 13.

- Erickson, B. (2015). Embodied heritage on the French River: Canoe routes and colonial history: Embodied heritage. The Canadian Geographer / Le Géographe Canadien, 59(3), 317–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12171

- Leitāo, L. (2017). Bridging the Divide Between Nature and Culture in the World Heritage Convention: An Idea Long Overdue? George Wright Forum, 42(2), 195–210.

- Linton, J., & Budds, J. (2014). The hydrosocial cycle: Defining and mobilizing a relational-dialectical approach to water. Geoforum, 57, 170–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.10.008

- Noel, Lynn E. (Ed.). (1995). Voyages: Canada’s Heritage Rivers. St. John: Atlantic Centre for the Environment.

- Thompson, C. (2017, December 2). A Grand challenge. TheRecord.Com, p. Online.

Policies and reports

- Benjamin, L., Veale, B., Shipley, R., Galvan, K. J., & Davies, M. (2013, March). Arch, Truss & Beam: The Grand River Watershed Heritage Bridge Inventory. Retrieved from https://www.grandriver.ca/en/our-watershed/resources/Documents/CHRS/CHRS_2013_BridgeInventory.pdf

- Canadian Heritage River Board. (2017). Heritage Rivers System Principles, Procedures and Operational Guidelines 2017. Retrieved from http://chrs.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/PPOG_May-2017_edit-Oct-2019.pdf

- Canadian Heritage River System. (2010). Building a Comprehensive and Representative Canadian Heritage Rivers System: A Gap Analysis, Executive Summary. Retrieved from http://chrs.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/7543-Parc-Canada-PDF-EN-V05-Accessible.pdf

- Grand River Conservation Authority. (1994). The Grand Strategy for Managing the Grand River as a Canadian Heritage River. Retrieved from https://www.grandriver.ca/en/our-watershed/resources/Documents/CHRS/CHRS_1994_GrandStrategy.pdf

- Grand River Conservation Authority. (2014, December). Background Briefing: Canadian Heritage River designation. Retrieved from https://www.grandriver.ca/en/learn-get-involved/resources/Documents/GRCA_factsheet_Heritage.pdf

- Grand River Conservation Authority. (2019). Strategic Plan 2019-2021. Retrieved from https://www.grandriver.ca/en/who-we-are/resources/Documents/Strategic-Plan_2019.pdf

- Larion, M., & Grand River Conservation Authority. (2014). Canadian Heritage Rivers System Ten Year Monitoring Report 2004-2014. Retrieved from Grand River Conservation Authority website: https://www.grandriver.ca/en/our-watershed/resources/Documents/Final-CHRS-10-Year-Monitoring-Report-2004-2014.pdf

- Praxis Research Associates. (2018). The History of the Mississaugas of the New Credit. Retrieved from http://mncfn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/The-History-of-MNCFN-FINAL.pdf

- Six Nations Council Lands and Resources Department. (2015, March). Six Nations of the Grand River: Land Rights, Financial Justice, Resolutions. Wildlife Management Office.

- United Nations. (n.d.). Sustainable Development Goals Knowledge Platform – Goal 11. Retrieved from www. to confirm.

- Veale, B. J., & Grand River Conservation Authority. (2004). The Grand River, Ontario: A decade in the Canadian heritage rivers system, a review of the Grand strategy 1994-2004. Retrieved from Grand River Conservation Authority website: https://www.grandriver.ca/en/our-watershed/resources/Documents/CHRS/CHRS_10YearReport.pdf

- Wright, J., & Imhof, J. (2001, May). Technical Background Report for the Grand River Fisheries Management Plan. Retrieved from https://www.grandriver.ca/en/our-watershed/resources/Documents/Fishery/Fishery_ManagementPlan_TechReport.pdf

Websites

- Filice, M. (2016). Haldimand Proclamation. Retrieved November 27, 2019, from The Canadian Encyclopedia website: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/haldimand-proclamation

- GRCA history. (2019, March 26). Retrieved December 4, 2019, from Grand River Conservation Authority website: https://www.grandriver.ca/en/who-we-are/GRCA-history.aspx

- Our watershed. (2019, June 28). Retrieved December 4, 2019, from Grand River Conservation Authority website: https://www.grandriver.ca/en/our-watershed/Our-Watershed.aspx

- Syed, Fatima. “Doug Ford Orders ‘wind down’ of Non-Essential Conservation Authority Programs.” National Observer, 19 Aug. 2019, https://www.nationalobserver.com/2019/08/19/news/doug-ford-orders-wind-down-non-essential-conservation-authority-programs.