Conserving Winnipeg’s Modern Heritage: Envelope Rehabilitation and Materials Reuse

Case Study prepared by Hadi Tamim, Carleton University

Keywords: Rehabilitation, Modern Heritage, Performance, Urban Design, Envelope, Material Reuse, Sustainability

LESSONS LEARNED

The Workers Compensation Board (WCB) of Manitoba building is an elegant modernist mid-century office building that recently enhanced its energy performance by rehabilitating its entire envelope. The notable feature worth learning from was that the rehabilitation process was achieved through restoring the existing envelope cladding panels and adding slight interventions for improvement in performance, rather than a major overhaul of the façades. The methodology adopted for this conservation process maintained the heritage value of this building to protect the narration of how this building contributed to the evolution of the entire city.

The city of Manitoba evolved radically during the mid-century modernist movement and urban sprawl in the 1960s. This flourishment erected longstanding modernist buildings across the city, notably the Worker’s Compensation Board of Manitoba Building – previously for Monarch Life. This building is a critical case study that demonstrates a leading rehabilitation approach in heritage conservation. Today’s technological advancements are utilized to prolong the lifespan of this modernist building and enhance its energy performance through a complete envelope revamp. The rehabilitation approach was comprised of the dismantling, repair, and reuse of the entire existing granite cladding for sustaining the high heritage value of its initial appearance, and diminishing tons of waste that are usually dumped into landfills. Simultaneously, this upgrade has allowed the building to meet updated building code requirements established by the National Building Code of Canada. Following its rehabilitation the building was designated by the city of Winnipeg in 2021, a reflection of the project’s careful preservation of character-defining design elements and materials.

After studying the strategy of intervention by the restorers of the WCB of Manitoba building to rehabilitate it, a comparison has been made to verify the approach relative to Standards and Guidelines for the Conservation of Historic Places (Parks Canada, 2010). Since it has a stone cladding system, it also has to undergo examination according to the CSA A371 Masonry Construction for Buildings in the Canadian Standards Association, as well as the National Building Code of Canada climatic condition requirements. Assessing the case study according to these standards and guidelines will contribute to the better understanding of the strategy of intervention and its level of success. This case study builds on extensive documentation available through existing case studies of the recent work, notably in Mark Brandt (2016) and Flaman (2021).

The following slides were presented in class on November 25 2021 as a summary that introduced the building, stated the main ideas, and initiated discussions amongst peers for new ideas.

DESCRIPTION

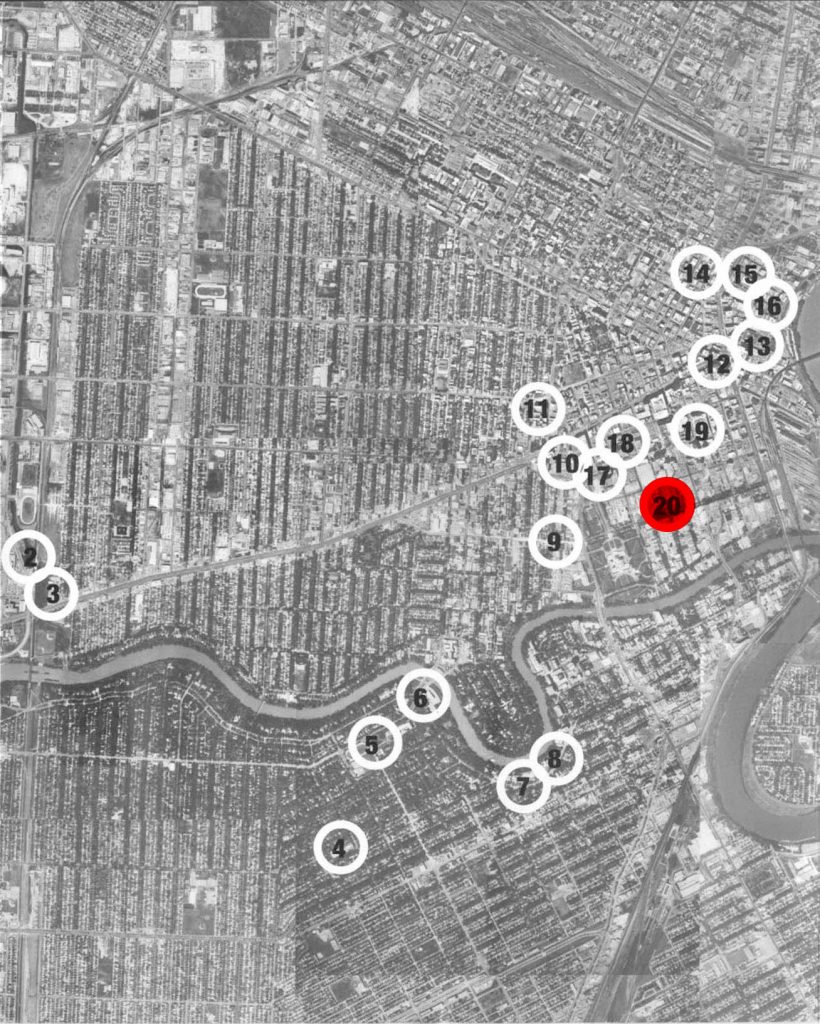

The WCB of Manitoba building, located at 333 Broadway, is an icon of urbanization in Winnipeg, an evolution that commenced in the 1950s when its rural villages and towns transformed into cities and urban complexes during the period of Modernism (Spasoff, 2012).

During the postwar international modern movement, the evolution of science and technology emerged as the hope for improving living conditions, and Manitoba witnessed societal evolution into modernity from rural communities. Prior to this era of optimism, Manitobans had resided in rural areas and small towns without any modern services. Then, a group of local architects endorsed modernism during the time of population movement and societal evolution, so the internationally trending style was integrated in Manitoba’s mid-century architecture. Nonetheless, the architects ensured that the buildings remain unique to the province in their identity (Flaman, 2021).

Another unique feature in the urbanization of Manitoba was that, unlike other cities, it maintained steady growth over time, instead of encountering a rapid urban influx. The threshold of over development that harms the environment was never exceeded. In fact, the WCB Building, alongside other mid-century buildings, resembles an era of prosperity in Manitoba when the boundaries of human achievements stretched to the moon and humanitarian goals were to abolish poverty. Basically, these buildings are a physical embodiment of the historical evolution towards the current version of Manitoba that has brought social, political, cultural, and technological advancement, thus, reinstating their heritage value (Sasoff, 2012).

The healthy urban economy prevalent at that time in Winnipeg allowed it to build one of the wealthiest collection of Modernist architecture buildings. The design of the WCB building was on of the state-of-the-art Modernist buildings. It portrayed the security of its corporation and its confidence in committing to the economic development of Winnipeg with its elegant façade, offering its clients and employees a place they can trust. In fact, the WCB building has been described as “one of the best examples of Modernist detailing and urban design, and a model of Modernist preservation” (Keshavjee and Enns 2006, 87). The reason behind its conservation was that buildings of such style reach an age where threatening issues begin to surface, and this symptom should be a warning to reassess all of Manitoba’s buildings from this era.

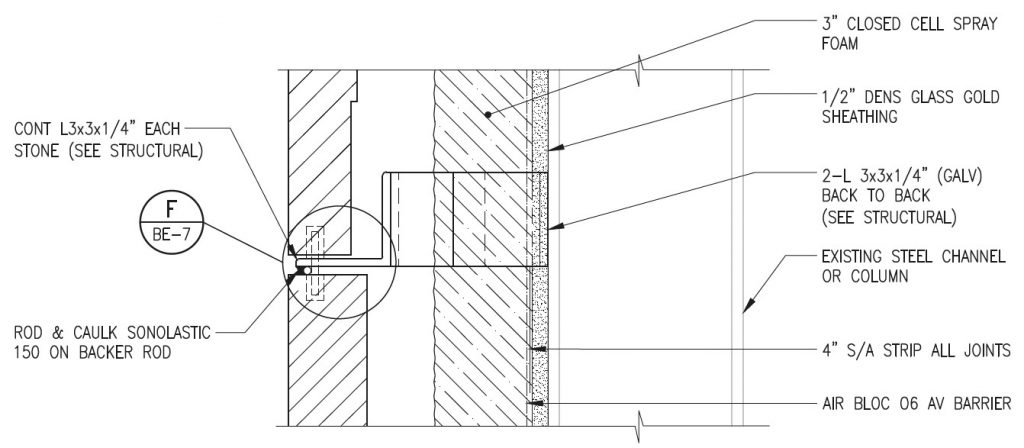

According to the National Building Code of Canada, and the Canadian Standards Association CSA A371: Masonry Construction, “stone less than 3 inches thick shall be individually supported versus stacked with weight bearing on the panels below,” as originally designed in the WCB building envelope (National Research Council of Canada, 2015). Consequently, the rehabilitation team designed an independent steel support system for the granite cladding panels across all the building. This also contributed to the decrease of thermal bridging by the protruding steel frame through the insulation and air barrier.

“4,044 granite stone panels were removed, repaired and replaced in their original location following asbestos abatement and the installation of a new high-performance building envelope system. Occurring at six primary locations around the building, and at every column at the main and sixth floor, new joints were detailed with stainless steel, a material used throughout the original construction and still present on the building façade and interior design.”

1×1 architecture

During the rehabilitation process, several options regarding the cladding were taken into consideration. One proposal was to install a new composite panel system that would be cheaper. However, the more expensive decision was taken that proposed the conservation and reinstallation of the existing stone panels since the granite itself was still in peak condition, but the anchorage system was failing. This decision to revamp the existing panels simultaneously avoided diverting 400 metric tons of granite into the landfill, and maintained the initial heritage identity of the building. Although these granite panels imposed a carbon footprint when they were originally imported from a different country, reusing them for the rehabilitation compensated for the original embodied energy since they are now considered locally acquired materials put into reuse.

TIMELINE

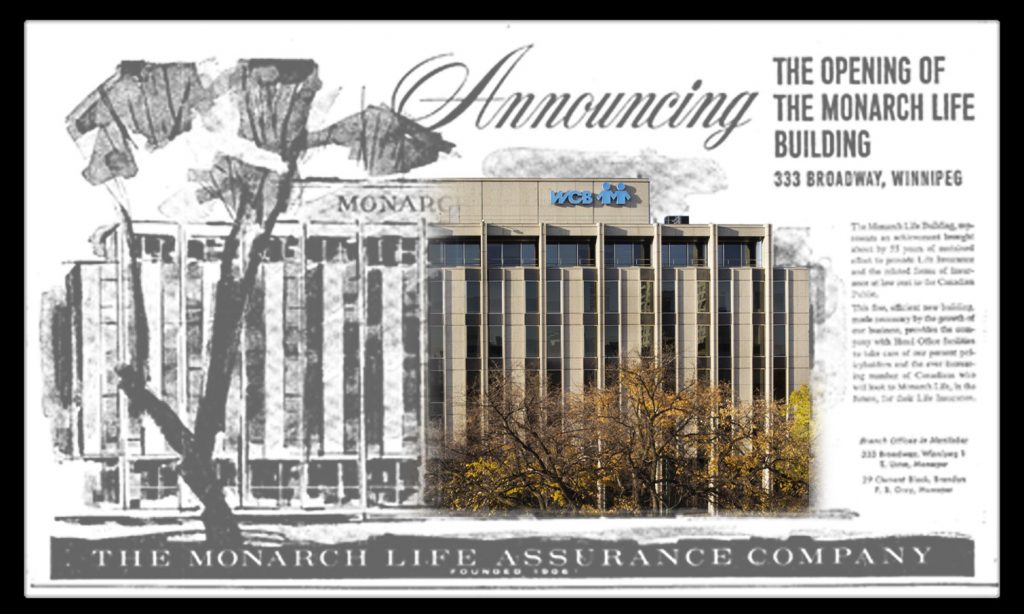

The building was originally erected for the Monarch Life Assurance Company, a Winnipeg founded company, that since 1906 was based in separate floors of another office building. Following a period of progressive growth, they constructed their own grand office structure in 1960 on Broadway, one of Winnipeg’s oldest and most prestigious boulevards (Winnipeg Architecture).

Created in 1873, Broadway Avenue was named by Hudson’s Bay Company as it was the primary east-west route for fur trade through its reserve in Winnipeg (Manitoba Historical Society). Today, Broadway is a wide central road defined by major historic buildings on each of its extremities: Union Station (1911) towards the east, and the Manitoba Legislative Building (1920) towards the west end. The Monarch Life assurance/now WCB building is located at the midpoint of these two landmarks of Winnipeg.

| 1873 | Broadway Avenue created/named |

| 1906 | Monarch Life Assurance Company founded in Winnipeg |

| 1960 | The building is constructed for Monarch Life Assurance Company |

| 1964 | Massey Medal Finalist |

| 1999 | The building is occupied by a new company, the Workers Compensation Board of Manitoba (Winnipeg Architecture) |

| 2009 | During a routine roof leak investigation, outward displacement was noticed in large granite cladding panels |

| 2010 | The National Building Code of Canada issues new standards for Building and Fire Codes that had to be integrated in the rehabilitation |

| 2013 | Restoration project completed Ecclesiastical Insurance Cornerstone Award (Adaptive Reuse/Rehabilitation) |

| 2021 | Municipally Designated Historic Building |

STAKEHOLDERS

Although not mentioned as part of the project, impacts on Winnipeg and Manitoba Indigenous peoples on a project of these symbolic values and location should be considered. Amongst the major cities in Canada, the City of Winnipeg has the largest Indigenous Population,12.2% of the entire Indigenous population is found in Winnipeg. They identify as Metis, First Nations, Inuit, and others (Government of Canada). Moreover, on their website, the Workers Compensation Board of Manitoba references a number of initiatives related to Manitoba Indigenous workers, youth and communities.

- Owners/Users: This office building on a strategic location in the city had different companies occupying it throughout history.

- Monarch Life Assurance Company and their staff (previous)

- Worker’s Compensation Board of Manitoba and their staff (current)

- Organizations: Organizations involved or interested in the rehabilitation of the Workers Compensation Board of Manitoba building include:

- City of Winnipeg

- Manitoba Historical Society

- Province of Manitoba

- Parks Canada

- Consultants: The execution of this rehabilitation project required joint efforts from different consultants that are experts in certain fields needed for the project. The original consultant team included:

- James Donahue (architect) with Smith Carter Searle Associates Architects and Engineers

- Crosier Kilgour and Partners Ltd.

- Akman Construction Ltd.

- Bowyer Boag, Winnipeg (Mechanical, 1960)

- Kummen Shipment Ltd. Winnipeg (Electrical, 1960)

- Coldspring Granite Ltd.

- Alpha Masonry

- Rehabilitation Consultants: The same architects who designed the building initially were rehired to conduct the rehabilitation process.

- Prime Consultant, Structural and Building Envelope: Crosier Kilgour & Partners Ltd.

- Architect of Record: 1×1 architecture inc.

- Design Consultant: Smith Carter Architects and Engineers

- Construction Manager: Akman Construction (1×1 Architecture)

- H.H.Angus, Toronto (Engineering)

- Bird Construction Company (Contractor)

HERITAGE

Cultural Heritage: The WCB, former Monarch Life Building, was designated as a historic resource by the city of Winnipeg/province of Manitoba on February 25, 2021. The city of Winnipeg lists the following following exterior elements as character-defining :

- “a generally open, dark granite and pre-cast concrete panelled podium on all four sides;

- the six-storey granite-clad building with penthouse located on a wide pedestal of dark stone on the north side of Broadway from Hargrave Street to Carlton Street, its main façades facing south onto Broadway and north onto a parking lot, its east façade facing Hargrave Street and its west façade facing Carlton Street;

- its main (south) and rear (north) façades with their glass main floor and cantilevered upper storeys with thin columns running from the pedestal to the top of the smaller sixth floor, bays of angled windows in rectilinear openings, dark spandrels and stainless steel accenting; and,

- its windowless east and west façades with granite panels and stainless steel bands.” (List of Historical Resources – Planning, Property and Development Department – City of Winnipeg).

The WCB building was designed by James Donahue, a prominent Manitoba born and trained modernist architect, alongside Smith Carter. In the Harvard School of Design, Donahue was the first Canadian graduate in architecture under the mentorship of Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer who were of the greatest Modernist architects back then and even today. Later, he returned to Winnipeg to design multiple buildings across Manitoba for different clients. From 1946 until 1963, he was a faculty member in the architecture school of the University of Manitoba (Spasoff, p.39).

Modern heritage has had its impact on the urban context that emphasizes its value. As mentioned in the description, the WCB, alongside the rest of the mid-century buildings of Winnipeg, demonstrates the historical evolution of the city, a trait that reinforces its heritage value. The building narrates a time where society evolved from its rural communities and small towns into a modern society with more services, conveniences, and facilities. Hopeful progression that the WCB building resembled as a tangible memory took its toll on cultural, political, social, and technological aspects.

Moreover, the feature that promotes the value of the WCB building over other mid-century buildings is its expensive material palette. During the 1960s, limestone was locally acquired across western Canada and aesthetically appealing, so it was used as a cladding on the exterior instead of concrete. However, these facades of mid-century modernist buildings have been severely damaged due to extreme weather conditions for the past two decades, and they have been replaced or even demolished. On the other hand, the WCB building resorted to an eccentric choice of cladding, granite. This prestigious touch portrayed the impression of establishment and security, a suitable image for an insurance company. An article in Western Construction and Building from 1962 on the Monarch Life building (now WCB building) reported that it had imported its granite cladding panels from Coldspring, a granite fabricator based in Minnesota (p.34). In fact, the same stones were still in production by the company during the rehabilitation process, so new coping stones from the same granite were ordered to install for the new upgraded roofing membrane.

The building sits on a “dark pedestal of smooth marble” extending from Broadway, contributing to the urban design of public spaces in the region. Throughout the façade, the evenly spaced grey granite cladding varies in textures of smooth and rough finishes. The façade is regularly interrupted by columns based on the ground floor, extending all the way to the roof. Another dynamic feature is the use of darker materials as accents, as well as the angled windows that animate the elevation of the building. All of the mentioned vertical elements extending along the granite cladding break the flatness of the overall façade. The intricate finishing of the envelope through the poetic use of different elements that accentuate one another is one of the character-defining elements of the WCB building.

The conservation process undertaken on the WCB building was based on meticulous historical research (Peterson, 2017) and abidance to the Standards and Guidelines for the Conservation of Historic Places in Canada although it was not yet formally designated for its historical significance back then (1×1 Architecture). In fact, one decision that adheres to the conservation standards was to intentionally make the new intervention features vividly distinguishable, yet subordinate to the initial cladding system, and allow reversibility as an option for the future.

SUSTAINABILITY

The subsections of sustainability in this case study are quite interconnected with one another.

Environmental Sustainability: Most mid-century buildings that adopted the international style of Modernist architecture are almost midway through their life expectancy, so they reached an age where several threatening issues have arisen. However, unlike typical office building envelopes of the 1960s, the WCB building was designed with a higher proportion of solid wall than window openings, in an attempt to minimize the amount of glass.

The discovery of the deteriorated state of the façade was during a roof leak investigation in 2009, when large granite cladding panels were spotted displaced outward. Conducted studies inferred that the WCB building envelope was extremely inefficient relative to the extreme Canadian climate. The wall system did not include sheathing between the cladding and the insulation, so moisture would directly penetrate and damage the inside of the wall. This weakness caused vapor leakage and air moisture leading to condensation and precipitation penetration from the exterior which deteriorated the state of the stone panels.

The rehabilitation plan aimed to correct all those operational deficiencies the envelope had been encountering and correct the problems in it. The main objective was to add a reinforcing layer of air and vapor barrier through an exterior sheathing layer. For drainage and ventilation, an air cavity was left behind the stone cladding. The granite panels were in excellent condition with only minor cracks and fractures that could be treated, unlike the entire failing envelope system.

The main sustainability approach initiated by the rehabilitation was to reuse the existing granite panels instead of installing an entirely new composite panel system. The conservation and reinstallation of the existing panels avoided dumping 400 metric tons of granite in the local landfill. Instead, the 4,044 granite panels were delicately removed, cleaned, and repaired in a storage facility away from the site, where they were thoroughly examined for fractures to repair before reinstalling them. (400 or 500 metric tons? see Crosier Kilgour)

Condition behind removed stone cladding panel before rehabilitation (source: John Wells, Crosier Kilgour and Partners Ltd.)

Restored Granite Cladding Panels Stored Off-Site (source: buildingresilience.ca)

Social Sustainability: During the project the building had to remain in use. Project delivery was divided in a strategic way to avoid interrupting the ongoing work inside and maintain the ongoing construction. This was a heritage and user-friendly approach for project delivery, where minimal disturbance of the building activity occurred for the duration of the two-year construction process.

Cultural Sustainability: The conservation work as performed was based on extensive historical research and commitment to Parks Canada’s 2010 Standards and Guidelines for the Conservation of Historic Places in Canada. The reuse of the existing material preserved the building’s original appearance, so it maintained its heritage value as a prominent icon of the cultural evolution of Winnipeg into an urban realm. Based on the description of the rehabilitation process elaborated above in depth, they abide by the following standards.

- Conserve the heritage value of an historic place.

- Conserve heritage value by adopting minimal intervention approach.

- Recognize each historic place as a physical record of its time, place and use.

- Protect and stabilize an historic place until any subsequent intervention is undertaken.

- Evaluate existing condition of character-defining elements to determine the appropriate intervention needed.

- Repair character-defining elements by reinforcing their materials using recognized conservation methods.

- Make any intervention needed to preserve character-defining elements physically and visually compatible with historic place and identifiable on close inspection.

- Repair rather than replace character-defining elements.

- Conserve heritage value when creating new additions or new construction (Parks Canada, 2010, pp. 32–37)

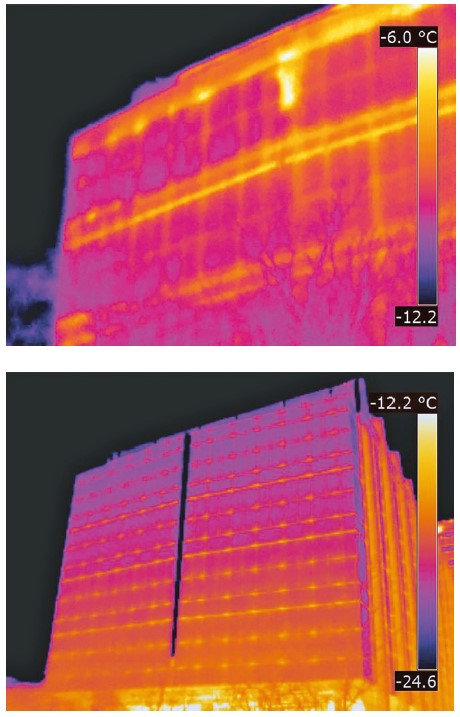

Economic Sustainability: Economic benefits over the longer term can be associated with reduced operational energy costs that result from the project. Upon reinforcing the insulation of the walls with exterior air-vapor barrier, the wall value of insulation increased from R-9 to R-22, so the thermal bridging level has been significantly reduced, thus, decreasing energy use expenses for heating, and providing additional interior comfort for the users. Broader economic sustainability perspectives are assessed in the section on Measurement with respect to related Sustainable Development Goals.

Thermographic image of the west facade before the construction project (top) and following project completion (bottom). The top image shows bright flares indicate major air leakage along the top of the building, and the orange/yellow grid pattern represents thermal bridging from structural steel framing. The bottom image shows fine orange/yellow lines show the location of the projecting steel plates added for stone support, a result of conductive heat loss from the framing. (source: John Wells, Crosier Kilgour and Partners Ltd.)

MEASUREMENT

The conservation approach for rehabilitating the Workers Compensation Board of Manitoba building adhered to all of the guidelines in hopes to maintain its heritage value and earn recognition from heritage and sustainability organizations. Also, the building strictly abided by the updated National Building Code standards and requirements of its category with respect to climate and material. This rehabilitation case study also contributed to the list of requirements indicated by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Manitoba Green Building Program: The Manitoba governmental organizations are committed to promoting sustainable building. Their policies and criteria are clearly stated in the Green Building Program of Manitoba.

These two goals by Manitoba’s Green Building Policy are achieved by rehabilitation of the WCB building envelope:

- During the construction phase, daily indoor activity was uninterrupted.

- Also, the initial goal of rehabilitating the envelope was to enhance the energy performance of the building, so that goal was achieved as well.

United Nations 2015-2030 Sustainable Development Goals: The case study contributes to the Sustainable Development Goals the United Nations hopes to achieve by 2030, including by tackling two of its nine goals.

| SDG | Comment re WCB |

| Goal 9: Build Resilient Infrastructure, Promote Sustainable Industrialization and Foster Innovation Target 9.4 By 2030, upgrade infrastructure and retrofit industries to make them sustainable, with increased resource-use efficiency and greater adoption of clean and environmentally sound technologies and industrial processes, with all countries taking action in accordance with their respective capabilities | Upon the rehabilitation of the envelope, the WCB building has contributed to this goal through increasing the energy performance of the overall building. |

| Goal 11: Make Cities, Inclusive, Safe, Resilient, and Sustainable Target 11.6 By 2030, reduce the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities, including by paying special attention to air quality and municipal and other waste management | Through reusing the existing granite panels, the rehabilitation of the case study building significantly decreased the amount of waste in Winnipeg. |

WORKS CITED

Book chapters/Articles

- Cooke, Travis et al.“ Workers Compensation Board of Manitoba.” In Bernard Flaman and Chandler McCoy, editors. Managing Energy Use in Modern Buildings, Case Studies in Conservation Practice. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute, 2021, pp. 159–171.

- “Crosier Kilgour & Partners Ltd, Developing Winnipeg’s Urban Landscape for More than 60 Years,” The Canadian Business Journal, 13 Dec. 2017, .

- Enns, Herbert, and Serena Keshavjee. Winnipeg Modern Architecture, 1945 to 1975. University of Manitoba Press, 2014.

Policies and reports

- City of Winnipeg. City of Winnipeg Green Building Policy. 14 Dec. 2011,

- Manitoba Green Building Program. Section 1, Government of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, 2013, pp. 1–3, Manitoba Green Building Policy, Program, Legislation & Reporting.

- National Research Council Canada, National Building Code of Canada. Institute for Research in Construction, 2015.

- Peterson, M. / Historic Buildings & Resources Committee. “333 Broadway, Monarch Life Building” (Long Report). City of Winnipeg, May 2017.

- Spasoff, Nicola. “James Donahue.” Modern Architecture in Manitoba An Overview. Historic Resources Branch Government of Manitoba, 2012, p. 39,

- Mark Thompson Brandt Architect & Associates Inc. Building Resilience: Practical Guidelines to Sustainable Rehabilitation of Buildings in Canada. Federal Provincial Territorial Ministers of Culture and Heritage in Canada. 2016.

- Parks Canada. The Standards and Guidelines for the Conservation of Historic Places in Canada. Canada’s Historic Places, 2010 (2nd edition).

- United Nations. “Goal 9: Industries, Innovation and Infrastructure,” United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.”

Websites

- 1×1 Architecture. “Workers Compensation Board.”

- City of Winnipeg Planning, Property & Development. “List of Historical Resources.” List of Historical Resources – Planning, Property and Development Department – City of Winnipeg, 6 Dec. 2021,

- Crosier, Kilgour & Partners.“Workers Compensation Board, 333 Broadway.”

- Government of Canada. First Nations in Manitoba – SAC-Isc.gc.ca. 31 Mar. 2021.

- Manitoba Historical Society. “MHS Resources: History in Winnipeg Streets.” MHS Resources: History in Winnipeg Streets.

- Manitoba Historical Society. “Historic Sites of Manitoba: Monarch Life Building / Workers Compensation Building (333 Broadway, Winnipeg).”

- Prairie Design Awards. “Workers Compensation Board Building Winnipeg, Manitoba.” Workers Compensation Board Building | Prairie Design Awards, 2014.

- Winnipeg Architecture Foundation. “Workers Compensation Board of Manitoba (Formerly Monarch Life Building).”

- Workers Compensation Board of Manitoba.

Banner image: Workers Compensation Board Building at 333 Broadway following envelope rehabilitation. Photo: 1×1 architecture inc., Gerry Kopelow, Lisa Stinner-Kun.